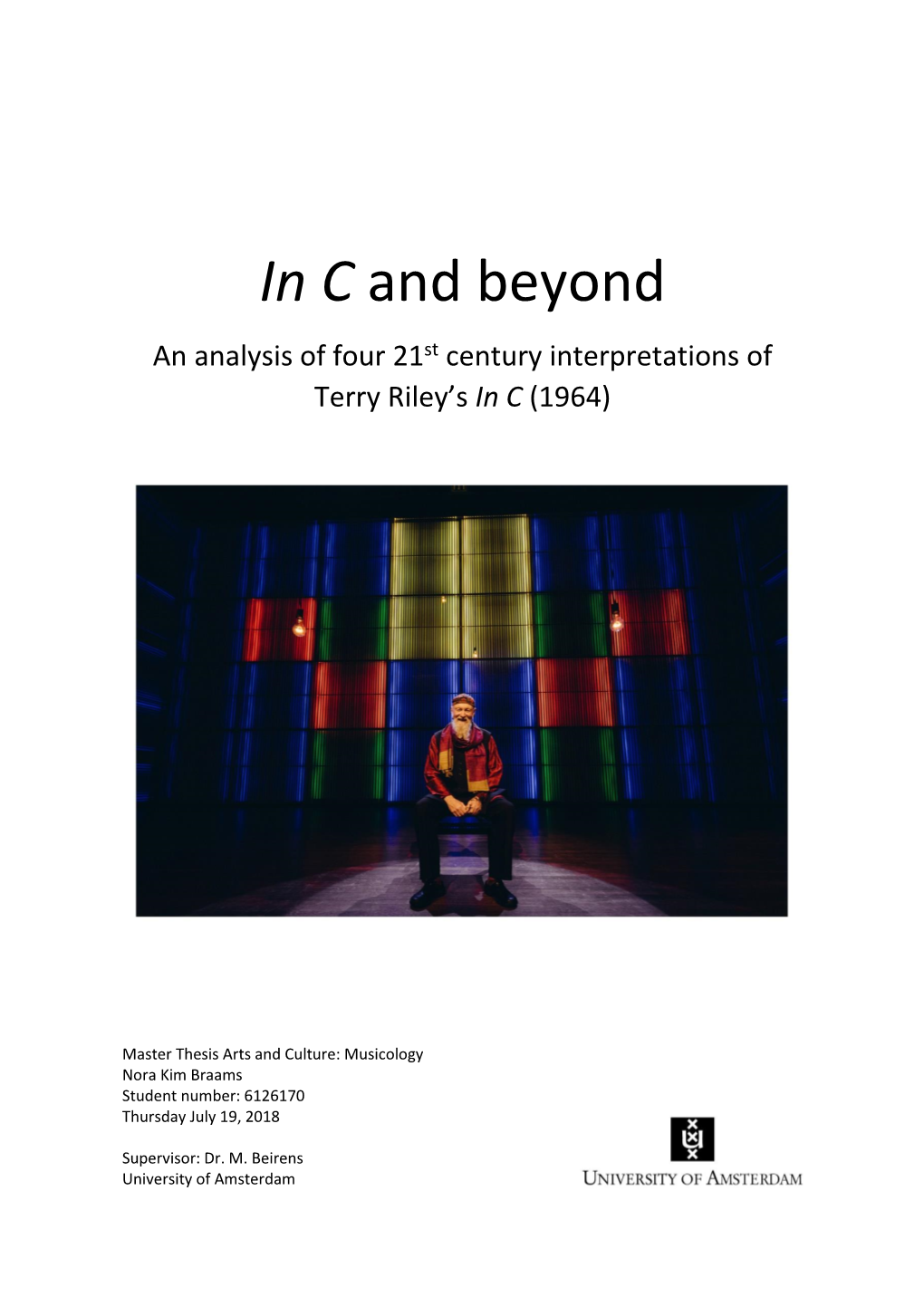

In C and Beyond an Analysis of Four 21St Century Interpretations of Terry Riley’S in C (1964)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Henry Flynt and Generative Aesthetics Redefined

1. In one of a series of video interviews conducted by Benjamin Piekut in 2005, Henry Flynt mentions his involvement in certain sci-fi literary scenes of the 1970s.1 Given his background in mathematics and analytic philosophy, in addition to his radical Marxist agitation as a member of 01/12 the Workers World Party in the sixties, Flynt took an interest in the more speculative aspects of sci-fi. “I was really thinking myself out of Marxism,” he says. “Trying to strip away its assumptions – [Marx’s] assumption that a utopia was possible with human beings as raw material.” Such musings would bring Flynt close to sci-fi as he considered the revision of the J.-P. Caron human and what he called “extraterrestrial politics.” He mentions a few pamphlets that he d wrote and took with him to meetings with sci-fi e On Constitutive n i writers, only to discover, shockingly, that they f e d had no interest in such topics. Instead, e R Dissociations conversations drifted quickly to the current state s c i 2 t of the book market for sci-fi writing. e h t ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊI’m interested in this anecdote in the as a Means of s e contemporary context given that sci-fi writing A e v has acquired status as quasi-philosophy, as a i t World- a r medium where different worlds are fashioned, e n sometimes guided by current scientific research, e G as in so-called “hard” sci-fi. While I don’t intend Unmaking: d n a here to examine sci-fi directly, it does allude to t n y the nature of worldmaking and generative l Henry Flynt and F aesthetics – the nature of which I hope to y r n illuminate below by engaging with Flynt’s work, e H Generative : as well as that of the philosophers Nelson g n i Goodman and Peter Strawson. -

VIVE LATINO Fotos: Paola Hidalgo

BUENOS AIRES.— La tercera y última jornada del festival Lollapalooza en Buenos CANCELAN Aires fue cancelada por los destrozos que causó una tormenta de lluvia y viento, por lo que decenas de miles se quedaron sin disfrutar de los conciertos de Pearl POR LLUVIA Jam (foto), David Byrne, LCD Soundsystem y Kygo, entre otros. Es la primera vez que debe suspenderse una de las fechas del Lollapalooza Argentina. (DPA) Foto: Daniel Betanzos EXCELSIOR LUNES 19 DE MARZO DE 2018 @Funcion_Exc x om.m c . funcion@gimm VIVE LATINO Fotos: Paola Hidalgo El grupo virtual creado POR AZUL DEL OLMO espacial en la pantalla. [email protected] Los gritos y la ova- por Damon ción no se hicieron es- Albarn fue el Con cinco discos de estudio GORILLAZ perar cuando sonaron y dos visitas previas, el gru- canciones como 19-2000, plato fuerte po británico Gorillaz regresó Saturnz Barz, Stylo y Char- de la segunda a México, donde 80 mil per- ger, provocando que el sonas lo esperaban con an- público se moviera en el jornada del siedad. Una ola de luz creada reducido espacio que les festival, en el con la incandescencia de los proporcionaba el recinto, que también celulares corría por las gradas Y PUNTO convirtiéndose así en parte del Foro Sol mientras el pú- Jamie Hewlett, Mike Smith, cuya máscara fue portada “Viva México”, lanzó Da- de la experiencia que ofre- actuaron blico esperaba la llegada de Jeff Wootton, Seye Adelekan, por Damon Albarn, mientras mon Albarn antes de que las cen los integrantes de Go- 2-D, Noodle, Murdoc Niccals Jesse Hackett, Gabriel Walla- M1A1 hacía saltar al público. -

September 1996 • That Magazine from Citr 101.9 Fm • Free

September 1996 • That Magazine From CiTR 101.9 Fm • Free Ar0i~+j(^<y-AAArJb\,. The Local Music Issue Also Featuring: The Tonics Sawaigi Taiko The Molestics BNU Under the Volcano Public Dreams Society PLUS: The 1996 Local Music Directory! CALL ANSWER. FOR MESSAGES THAT ARE MXJXJm /0FLAKEY ROOMMATE PROOF. No more trying to decode messages will alleviate the frustration of roommates scribbled on the back of Cheese Puff taking your messages. Call Answer does bags. Because Call Answer from BC TEL 60 DAYS FREE not, however, alleviate the frustration takes clear, concise messages when of trying to get you're away from home. Or on the line. roommates to And when you sign up for new telephone scrub their own BCTEL service, you get two months free. Which 1-800-422-9966 tile mildew. 'Offer applies telephor restriction THURSDAY, 5th THE TONICS UBC STUDENTS APPRECIATION NIGHT SAWAGI TAIKO STRANGE UNION, HEE-HAW, BNU & CUSTER'S LAST BAND STAND THE MOLESTICS FRIDAY, 6th PUBLIC DREAMS | THE SPIRIT MERCHANTS (AUSTRALIA'S} JEFF LANG MECCA NORMAL UNDER THE VOLCANO SATURDAY, 7th RAY CONDO •Si THE RICOCHETS with SURFDUSTERS editrix VANCOUVER SPBQAL miko hoffman THURSDAY, 12th art director BASSUNES ken paul COWSHEAD CHRONICLES INDEPENDENCE DAV 3 ad rep VELVETS CHRISTIAN COMICS CONTENTION, WITH QUEAZY, kevin pendergraft IMAGINEERS, & JAR production manager INTERVIEW HELL barb yamazaki SEVEN INCH FRIDAY 13th graphic design/layout BETWEEN THE LINES JAZZBERRY RAIN/1 atomos, ken paul, scratch, UNDER REVIEW suki smith, barb y SATURDAY, 14th production REAL LIVE ACTION MUSCLE BITCHES frank?, miko gh, megan ClTRjSflARTS PUNCHED UNCONSCIOUS, BRUNDLE FLY mallett, tristan, barby photography/illustrations OjrfTHE DIAL barb, cat, paul clarke, JEPTEMBER DATEBOOK ><&&^ FRI, SAT, 20th & 21st adam monahan, suki smith, Folk Funk'en Hemp Bash! marlene yuen Noah's Great Rainbow, Cozy Bones, 10ft contributors Henry, Silicone Souls, Peal, Mya Eaxell, Side barbara a, britt a, andrea & Shows, and more! Info: 730-1808 amber dawn, elvira b, YES^I^EY ARE FRO^'VANCOUVER. -

21-Asis Aktualios Muzikos Festivalis GAIDA 21Th Contemporary Music Festival

GAIDA 21-asis aktualios muzikos festivalis GAIDA 21th Contemporary Music festival 2011 m. spalio 21–29 d., Vilnius 21–29 October, 2011, Vilnius Festivalio viešbutis Globėjai: 21-asis tarptautinis šiuolaikinės muzikos festivalis GAIDA 21th International Contemporary Music Festival Pagrindiniai informaciniai rėmėjai: MINIMAL | MAXIMAL • Festivalio tema – minimalizmas ir maksimalizmas muzikoje: bandymas Informaciniai rėmėjai: pažvelgti į skirtingus muzikos polius • Vienos didžiausių šiuolaikinės muzikos asmenybių platesnis kūrybos pristatymas – portretas: kompozitorius vizionierius Iannis Xenakis • Pirmą kartą Lietuvoje – iškiliausio XX a. pabaigos lenkų simfoninio kūrinio, Henryko Mikołajaus Góreckio III simfonijos, atlikimas • Dėmesys tikriems šiuolaikinės muzikos atlikimo lyderiams iš Prancūzijos, Vokietijos ir Italijos Partneriai ir rėmėjai: • Intriguojantys audiovizualiniai projektai – originalios skirtingų menų sąveikos ir netikėti sprendimai • Keletas potėpių M. K. Čiurlioniui, pažymint kompozitoriaus 100-ąsias mirties metines • Naujų kūrinių užsakymai ir geriausi Lietuvos bei užsienio atlikėjai: simfoniniai orkestrai, ansambliai, solistai Festivalis GAIDA yra europinio naujosios muzikos kūrybos ir sklaidos tinklo Réseau Varése, remiamo Europos Komisijos programos Kultūra, narys. The GAIDA Festival is a member of the Réseau Varése, European network Rengėjai: for the creation and promotion of new music, subsidized by the Culture Programme of the European Commission. TURINYS / CONTENT Programa / Programme.......................................................................................2 -

Drone Music from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Drone music From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Drone music Stylistic origins Indian classical music Experimental music[1] Minimalist music[2] 1960s experimental rock[3] Typical instruments Electronic musical instruments,guitars, string instruments, electronic postproduction equipment Mainstream popularity Low, mainly in ambient, metaland electronic music fanbases Fusion genres Drone metal (alias Drone doom) Drone music is a minimalist musical style[2] that emphasizes the use of sustained or repeated sounds, notes, or tone-clusters – called drones. It is typically characterized by lengthy audio programs with relatively slight harmonic variations throughout each piece compared to other musics. La Monte Young, one of its 1960s originators, defined it in 2000 as "the sustained tone branch of minimalism".[4] Drone music[5][6] is also known as drone-based music,[7] drone ambient[8] or ambient drone,[9] dronescape[10] or the modern alias dronology,[11] and often simply as drone. Explorers of drone music since the 1960s have included Theater of Eternal Music (aka The Dream Syndicate: La Monte Young, Marian Zazeela, Tony Conrad, Angus Maclise, John Cale, et al.), Charlemagne Palestine, Eliane Radigue, Philip Glass, Kraftwerk, Klaus Schulze, Tangerine Dream, Sonic Youth,Band of Susans, The Velvet Underground, Robert Fripp & Brian Eno, Steven Wilson, Phill Niblock, Michael Waller, David First, Kyle Bobby Dunn, Robert Rich, Steve Roach, Earth, Rhys Chatham, Coil, If Thousands, John Cage, Labradford, Lawrence Chandler, Stars of the Lid, Lattice, -

For Piano Four-Hands 21:37 Donald Berman and John Mcdonald, Piano

pg 8 pg 1 1. SHAKE THE TREE (2005) for piano four-hands 21:37 Donald Berman and John McDonald, piano BRAIDED BAGATELLES (2001-02) 18:35 Moritz Eggert, piano 2. Cadenza 2:26 3. Marking the Field 2:38 4. Stretching 3:22 5. Marching 2:27 6. Floating 2:40 7. Flying 4:52 PIANO SONATA NO.2, “THE BIG ROOM” (1993-99) 27:05 Erberk Eryilmaz, piano 8. Clouds Are Scattering 6:16 9. The Big Room 9:05 10. The World Turned Upside Down 11:44 --67: 04-- pg 2 pg 7 My piano music is a continuing diary of my growth as a composer. And that’s Erberk Eryilmaz, a native of Turkey, is a composer, pianist, and conductor. He ironic, since I’m a very modest pianist. But starting with my first sonata, “Spi- completed his undergraduate studies at the Hartt School, University of Hartford, ral Dances” (1984), it’s been the medium where I can test out ideas big and and is currently pursuing graduate studies at Carnegie Mellon University. He is small, some very spacious and ambitious, others occasional, experimental, and a founder and co-director of the Hartford Independent Chamber Orchestra. lighter-hearted. The culmination of this approach is Shake the Tree, perhaps the most virtuosic and architecturally ambitious work I’ve ever written. Two of John McDonald is a composer who tries to play the piano and a pianist who its major predecessors are Braided Bagatelles, a bravura evocation of variation tries to compose. He is Professor of Music and Department Chair at Tufts Uni- form, mixed with elements that verge on Dada, and my Piano Sonata No. -

Multi-Cultural. Dinner" Feast Prez: Search Firm Gauges'baruch

::- ~.--.-.;::::-:-u•._,. _._ ., ,... ~---:---__---,-- --,.--, ---------- - --, '- ... ' . ' ,. ........ .. , - . ,. -Barueh:-Graduate.. -.'. .:~. Alumni give career advice to Baruch Students.· Story· pg.17 VOL. 74, NUMBER 8 www.scsu.baruch.cuny.edu DECEM·HER 9, 1998 Multi-Cultural. Dinner" Feast Prez: Search Firm Gauges'Baruch. Opinion By Bryan Fleck Representatives from Isaacson Miller, a national search firm based in -Boston and San Francisco, has been hired by the Presidential Search Committee, chaired by Kathleen M. Pesile, to search for candidates for a permanent presi dent at Baruch College. The open forum on December 7 was held in order for the search firm to field questions and get the pulse of the Baruch community. Interim president Lois Cronholm is _not a candidate, as it is against CUNY regulations for an interim --------- president to become a full-time pres- ident. The search firm will gather the initial candidates, who will be . further screened by the Presidential " Search Committee, but the final choice lies with the CUNY Board of Trustees.' According to David Bellshow, an ......-.. ~.. Isaacson-Miller representative, the '"J'", average search takes approximately ; six months. Among the search firm's experience in the field of education ----~- - ..... -._......... *- -_. - -- -- _._- ...... -_40_. '_"__ - _~ - f __•••-. __..... _ •• ~. _• in NY are Columbia University and ... --- -. ~ . --. .. - -. -~ -.. New York University. In ~additi6n,, , New plan calls'for total re'structuririg the search fum also works with GovernDlents small and large foundations and cor ofStudent porations. By Bryan Fleck at large, would be selected from any The purpose ofthe open forum was In an attempt to strengthen undergraduate candidate. for the representatives of Isaacson . -

City Research Online

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by City Research Online City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. ORCID: 0000-0002-0047-9379 (2019). The Historiography of Minimal Music and the Challenge of Andriessen to Narratives of American Exceptionalism (1). In: Dodd, R. (Ed.), Writing to Louis Andriessen: Commentaries on life in music. (pp. 83-101). Eindhoven, the Netherlands: Lecturis. ISBN 9789462263079 This is the published version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/22291/ Link to published version: Copyright and reuse: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] The Historiography of Minimal Music and the Challenge of Andriessen to Narratives of American Exceptionalism (1) Ian Pace Introduction Assumptions of over-arching unity amongst composers and compositions solely on the basis of common nationality/region are extremely problematic in the modern era, with great facility of travel and communications. Arguments can be made on the bases of shared cultural experiences, including language and education, but these need to be tested rather than simply assumed. Yet there is an extensive tradition in particular of histories of music from the United States which assume such music constitutes a body of work separable from other concurrent music, or at least will benefit from such isolation, because of its supposed unique properties. -

A Place – a Time Eva-Maria Houben

a place – a time percussion (1 player) eva-maria houben © edition wandelweiser 2021 catalogue number ew16.359 a place – a time flying leaves for a percussionist eva-maria houben 2021 for aaron butler. a place: a place outdoors or indoors where you could have a good mind to spend a good time. a time: a time you spend at a certain place staying there for a while. maybe you are inviting the light, the wind, or the thunderstorm to enter. maybe you are inviting the rustling foliage, the run of water, the speaking stones, the branches, the birdsongs, the traffic, the working noises, or fragments of speaking voices or shouts to accompany you. finding a place filling the place with one’s own breath feeling the special atmosphere of the place putting together some loose sheets that could respond to this place performing—any order of the sheets, any order of the sounds on one sheet ending somehow, somewhen the score opens for all sounds of the environment. intervening and letting (something) happen have the same nature as intentional activities. the score touches both realms of actively doing something and actively letting something be. here and there undetermined instrumentation. all sounds are (rather) soft. repetition sign: number of repetitions ad libitum. all sounds find themselves in a one-line system. sometimes you find two, three or more sounds distributed above, on, or below the line: the different distances from the line for an instrument with pitched sounds indicate higher or lower (defined) pitches, not exactly a certain pitch. the sounds of an unpitched instrument appear in the same way in different distances from the line as different tones (of the material / instrument); this difference of ‘tones’ depends on different touch points. -

Chapter Three Minimal Music

72 Chapter Three Minimal music This chapter begins with a brief outline of minimal music in the United States, Europe and Australia. Focusing on composers and stylistic characteristics of their music, plus aspects of minimal music pertinent to this study, it helps the reader situate the compositions, composers and events referred to throughout the thesis. The chapter then outlines reasons for engaging students aged 9 to 18 years in composing activities drawn from projects with minimalist characteristics, reasons often related to compositional or historical aspects of minimal music since the late 1960s. A number of these reasons are educational, concerned with minimalism as an accessible teaching resource that draws on students’ current musical knowledge and offers a bridge from which to explore musics of other cultures and other contemporary art musics. Other reasons are concerned with the performance capabilities of students, with the opportunity to introduce students to a contemporary aesthetic, to different structural possibilities and collaboration and subject integration opportunities. There is also an educational need for a study investigating student composing activities to focus on these activities in relation to contemporary art music. There are social reasons for engaging students in minimalist projects concerned with introducing students to contemporary arts practice through ‘the new tonality’, involving students with a contemporary music which is often controversial, and engaging students with minimalism at a time of particular activity and expansion in the United States and in Australia. 3.1 Minimalism Minimalism is an aesthetic found across a number of different art forms – architecture, dance, visual art, theatre, design and music - and at the beginning of the twenty-first century, it is still strongly influential on many contemporary artists. -

System of a Down Molds Metal Like Silly Putty, Bending and Shaping Its Parame- 12 Slayer's First Amendment Ters to Fit the Band's Twisted Vision

NEW: LOUD ROCK CRUCIAL SPINS CHART LOW TORTOISE 1111 NEW MUSIC REPORT Uà NORTEC JACK COSTANZO February 12, 20011 www.cmj.com COLLECTIVE The Twisted Art-Metal Of SYSTEM OF ADOWN 444****************444WALL FOR ADC 90138 24438 2/28/388 KUOR - REDLAHDS FREDERICK SUER S2V3HOD AUE unr G ATASCADER0 CA 88422-3428 IIii II i ti iii it iii titi, III IlitlIlli lilt ti It III ti ER THEIR SELF TITLED DEBUT AT RADIO NOW • FOR COLLEGE CONTACT PHIL KASO: [email protected] 212-274-7544 FOR METAL CONTACT JEN MEULA: [email protected] 212-274-7545 Management: Bryan Coleman for Union Entertainment Produced & Mixed by Bob Marlette Production & Engineering of bass and drum tracks by Bill Kennedy a OADRUNNEll ACME MCCOWN« ROADRUNNER www.downermusic.com www.roadrunnerrecords.com 0 2001 Roadrunner Records. Inc. " " " • Issue 701 • Vol 66 • No 7 FEATURES 8 Bucking The System member, the band is out to prove it still has Citing Jane's Addiction as a primary influ- the juice with its new release, Nation. ence, System Of A Down molds metal like Silly Putty, bending and shaping its parame- 12 Slayer's First Amendment ters to fit the band's twisted vision. Loud Follies Rock Editor Amy Sciarretto taps SOAD for Free speech is fodder for the courts once the scoop on its upcoming summer release. again. This time the principals involved are a headbanger institution and the parents of 10 It Takes A Nation daughter who was brutally murdered by three Some question whether Sepultura will ever of its supposed fans. be same without larger-than-life frontman 15 CM/A: Staincl Max Cavalera. -

Extended Performance Techniques and Compositional Style in the Solo

EXTENDED PERFORMANCE TECHNIQUES AND COMPOSITIONAL STYLE IN THE SOLO CONCERT VIBRAPHONE MUSIC OF CHRISTOPHER DEANE Joshua D. Smith, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2008 APPROVED: Mark Ford, Major Professor Eugene Migliaro Corporon, Minor Professor Christopher Deane, Committee Member Terri Sundberg, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies Graham Phipps, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James C. Scott, Dean of College of Music Sandra L. Terrell, Dean of the Robert B. Toulouse School of Graduate Studies Smith, Joshua D., Extended performance techniques and compositional style in the solo concert vibraphone music of Christopher Deane. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2008, 66 pp., 1 table, 8 figures, 20 musical examples, references, 29 titles. Vibraphone performance continues to be an expanding field of music. Earliest accounts of the presence of the vibraphone and vibraphone players can be found in American Vaudeville from the early 1900s; then found shortly thereafter in jazz bands as early as the 1930s, and on the classical concert stage beginning in 1949. Three Pieces for Vibraphone, Opus 27, composed by James Beale in 1959, is the first solo concert piece written exclusively for the instrument. Since 1959, there have been over 690 pieces written for solo concert vibraphone, which stands as evidence of the popularity of both the instrument and the genre of solo concert literature. Christopher Deane has contributed to solo vibraphone repertoire with works that are regarded as staples in the genre. Deane’s compositions for vibraphone consistently expand the technical and musical potential of the instrument.