History of the Promenade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cape Town's Film Permit Guide

Location Filming In Cape Town a film permit guide THIS CITY WORKS FOR YOU MESSAGE FROM THE MAYOR We are exceptionally proud of this, the 1st edition of The Film Permit Guide. This book provides information to filmmakers on film permitting and filming, and also acts as an information source for communities impacted by film activities in Cape Town and the Western Cape and will supply our local and international visitors and filmmakers with vital guidelines on the film industry. Cape Town’s film industry is a perfect reflection of the South African success story. We have matured into a world class, globally competitive film environment. With its rich diversity of landscapes and architecture, sublime weather conditions, world-class crews and production houses, not to mention a very hospitable exchange rate, we give you the best of, well, all worlds. ALDERMAN NOMAINDIA MFEKETO Executive Mayor City of Cape Town MESSAGE FROM ALDERMAN SITONGA The City of Cape Town recognises the valuable contribution of filming to the economic and cultural environment of Cape Town. I am therefore, upbeat about the introduction of this Film Permit Guide and the manner in which it is presented. This guide will be a vitally important communication tool to continue the positive relationship between the film industry, the community and the City of Cape Town. Through this guide, I am looking forward to seeing the strengthening of our thriving relationship with all roleplayers in the industry. ALDERMAN CLIFFORD SITONGA Mayoral Committee Member for Economic, Social Development and Tourism City of Cape Town CONTENTS C. Page 1. -

South Africa, It Is Often Said, Is a World in One Said, Is a World It Is Often Africa, South Description Is This in No Other Arena Country

norway_sk 14/5/07 14:37 Page 452 452 south africa OBSERVATIONS FOR FILMMMAKERS www www. South Africa, it is often said, is a world in one . country. In no other arena is this description thelocationguide thelocationguide more apt than in the production of international commercials and films. Although in recent years, the enchanting Cape .com .com Town has become the centre of the international production industry, the city is also the perfect launch pad to a variety of exotic locations in Southern Africa and the Indian Ocean Islands, many of which enjoy an equable annual climate. Other areas of location production such as Gauteng and KwaZulu Natal offer wonderfully contrasting landscapes and have recently become quite an attraction for international commercial and film production. The high production values and developed film FILM COMMISSION, FILM BOARD or infrastructure on which Cape Town and the GOVERNMENT FILM LIAISON OFFICE Western Cape has built its reputation are National Film & Video Foundation complemented by spectacular locations, sunny Contact: Jackie Motsepe, Head of Marketing weather (in the Northern Hemisphere’s winter) & Public Affairs and 14-hour days of radiant light. E: [email protected] T: (27 11) 483 0880 W: www.nfvf.co.za The latest in equipment, post production and facilities are all available in South Africa, centred REGIONAL FILM OFFICES mainly around Cape Town and Gauteng Film Commission Gauteng. Its crews are Contact: Puisano Phatoli internationally renowned E: [email protected] for being the most cost T: (27 11) 833 0409 effective, talented and W: www.gautengfilm.org.za hard working English speaking crew Durban Film Office (Kwazulu Natal) available anywhere Contact: Toni Monti in the world. -

Gustavus Symphony Orchestra Performance Tour to South Africa

Gustavus Symphony Orchestra Performance Tour to South Africa January 21 - February 2, 2012 Day 1 Saturday, January 21 3:10pm Depart from Minneapolis via Delta Air Lines flight 258 service to Cape Town via Amsterdam Day 2 Sunday, January 22 Cape Town 10:30pm Arrive in Cape Town. Meet your MCI Tour Manager who will assist the group to awaiting chartered motorcoach for a transfer to Protea Sea Point Hotel Day 3 Monday, January 23 Cape Town Breakfast at the hotel Morning sightseeing tour of Cape Town, including a drive through the historic Malay Quarter, and a visit to the South African Museum with its world famous Bushman exhibits. Just a few blocks away we visit the District Six Museum. In 1966, it was declared a white area under the Group areas Act of 1950, and by 1982, the life of the community was over. 60,000 were forcibly removed to barren outlying areas aptly known as Cape Flats, and their houses in District Six were flattened by bulldozers. In District Six, there is the opportunity to visit a Visit a homeless shelter for boys ages 6-16 We end the morning with a visit to the Cape Town Stadium built for the 2010 Soccer World Cup. Enjoy an afternoon cable car ride up Table Mountain, home to 1470 different species of plants. The Cape Floral Region, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is one of the richest areas for plants in the world. Lunch, on own Continue to visit Monkeybiz on Rose Street in the Bo-Kaap. The majority of Monkeybiz artists have known poverty, neglect and deprivation for most of their lives. -

Revised Appeals Agenda 15 July 2020 Ab WD SB.Pdf

AGENDA APPEALS MEETING OF HERITAGE WESTERN CAPE APPEALS COMMITTEE TO BE HELD ON WEDNESDAY, 15 July 2020 at 9H00. Please note due to the lockdown, the meeting will be held via Microsoft Teams (https://teams.microsoft.com/downloads) To be a participant in the meeting, kindly email the item and contact details to [email protected] ahead of the scheduled time. Agenda No. Case number Item Reference No Documents to be tabled Matter Heritage Officer 1 Opening 2 Attendance 3 Apologies 4 Approval of Agenda 4.1 Dated: 15 July 2020 5. Approval of Pevious Minutes 5.1 Dated: 17 June 2020 6 Disclosure of Interest 7 Confidential Matters 8 Administrative Matters 8.1 Outcome of Tribunal Committee and Recent Court Decisions 8.2 Report back from HWC Council 8.3 Site Visits Conducted 8.3.1 None 8.4 Potential Site Visits 8.4.1 None MATTERS TO BE DISCUSSED Agenda No. Case number Item Reference No Documents to be tabled Matter Heritage Officer 9 MATTERS ARISING SECTION 34 MATTER FROM BELCOM Proposed demolition and partial demolition of various structure on - Erf HM/ROHM/ CAPE TOWN METROPOLITAN/ 9.1 19091609WD1129E 32564, Athlone Power Station, Corner Bhunga Avenue and N1 Highway Appeal documentation Matters Arising Waseefa Dhansay ATHLONE/ERF 32564NDEBOSCH / ERF 45530 Athlone SECTION 34 MATTER FROM BELCOM Appeal - Additions and Alterations - Erf 68058, 4 Smithers Road, HM/ CAPE TOWN METROPOLITAN/ KENILWORTH/ ERF 9.2 119110410WD1106E Revised propsal Matters Arising Waseefa Dhansay Kenilworth 68058 SECTION 34 MATTER FROM BELCOM/TRIBUNAL Proposed -

1 Additional Analysis on SAPS Resourcing for Khayelitsha

1 Additional analysis on SAPS resourcing for Khayelitsha Commission Jean Redpath 29 January 2014 1. I have perused a document labelled A3.39.1 purports to show the “granted” SAPS Resource Allocation Guides (RAGS) for 2009-2011 in respect of personnel, vehicles and computers, for the police stations of Camps Bay, Durbanville, Grassy Park, Kensington, Mitchells Plain, Muizenberg, Nyanga, Philippi and Sea Point . For 2012 the document provides data on personnel only for the same police stations. 2. I am informed that RAGS are determined by SAPS at National Level and are broadly based on population figures and crime rates. I am also informed that provincial commissioners frequently make their own resource allocations, which may be different from RAGS, based on their own information or perceptions. 3. I have perused General Tshabalala’s Task Team report which details the allocations of vehicles and personnel to the three police stations of Harare, Khayelitsha and Lingelethu West in 2012. It is unclear whether these are RAGS figures or actual figures. I have combined these figures with the RAGS figures in the document labelled A3.39.1 in the tables below. 4. I have perused documents annexed to a letter from Major General Jephta dated 13 Mary 2013 (Jephta’s letter). The first annexed document purports to show the total population in each police station for all police stations in the Western Cape (SAPS estimates). 5. Because the borders of Census enumerator areas do not coincide exactly with the borders of policing areas there may be slight discrepancies between different estimates of population size in policing areas. -

For the Demolition of No.19 and 17 Kloof Road, Sea Point on Erven 391 and 392 Fresnaye

Heritage Statement to accompany an application for a permit i.t.o. Section 34 of the NHRA (Act 25 of 1999) for the demolition of No.19 and 17 Kloof Road, Sea Point on Erven 391 and 392 Fresnaye The subject building from the west, across Kloof Road, with No.17 on the left and No.19 on the right. April 2016 Frik Vermeulen Pr. Pln BTech TRP (CTech) MPhil CBE (UCT) MSAPI MAPHP Professional Heritage Practitioner TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Location and Context 3. Historical Background 3.1 Brief Development History of Sea Point 3.2 History and Development of the Subject Site 4. Description 4.1 Erf 391 (No.19 Kloof Road) 4.2 Erf 392 (No.17 Kloof Road) 5. Statement of Significance 6. Consultation undertaken 7. Conclusion ANNEXURES SG Diagram: Erf 391 Fresnaye SG Diagram: Erf 392 Fresnaye Summary Sheet: No.19 Kloof Road (Erf 391) Summary Sheet: No.17 Kloof Road (Erf 392) Comment from Sea Point Fresnaye Bantry Bay Ratepayers and Residents Association Comment from City of Cape Town’s Environmental and Heritage Management Branch 1 1. Introduction The author has been appointed by K2013204008 (Pty) Ltd, the owner of Erven 391 and 392 Fresnaye, to make application for the total demolition of these two semi-detached houses. Since the building, which contains fabric dating back to c1890, is older than 60 years, a permit is required from Heritage Western Cape in terms of Section 34(1) of the National Heritage Resources Act (25 of 1999). It is proposed to redevelop the site and utilise the development opportunities offered by its strategic location and its General Business GB5 zoning, with a floor factor of 4.0 and permissible height of 25m. -

Load-Shedding Area 7

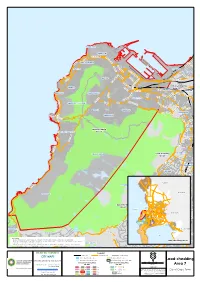

MOUILLE POINT GREEN POINT H N ELEN SUZMA H EL EN IN A SU M Z M A H N C THREE ANCHOR BAY E S A N E E I C B R TIO H A N S E M O L E M N E S SEA POINT R U S Z FORESHORE E M N T A N EL SO N PAARDEN EILAND M PA A A B N R N R D D S T I E E U H E LA N D R B H AN F C EE EIL A K ER T BO-KAAP R T D EN G ZO R G N G A KLERK E E N FW DE R IT R U A B S B TR A N N A D IA T ST S R I AN Load-shedding D D R FRESNAYE A H R EKKER L C Area 15 TR IN A OR G LBERT WOODSTOCK VO SIR LOWRY SALT RIVER O T R A N R LB BANTRY BAY A E TAMBOERSKLOOF E R A E T L V D N I R V R N I U M N CT LT AL A O R G E R A TA T E I E A S H E S ARL K S A R M E LIE DISTRICT SIX N IL F E V V O D I C O T L C N K A MIL PHILIP E O M L KG L SIGNAL HILL / LIONS HEAD P O SO R SAN I A A N M A ND G EL N ON A I ILT N N M TIO W STA O GARDENS VREDEHOEK R B PHILI P KGOSA OBSERVATORY NA F P O H CLIFTON O ORANJEZICHT IL L IP K K SANA R K LO GO E O SE F T W T L O E S L R ER S TL SET MOWBRAY ES D Load-shedding O RH CAMPS BAY / BAKOVEN Area 7 Y A ROSEBANK B L I S N WOO K P LSACK M A C S E D O RH A I R O T C I V RONDEBOSCH TABLE MOUNTAIN Load-shedding Area 5 KLIP PER N IO N S U D N A L RONDEBOSCH W E N D N U O R M G NEWLANDS IL L P M M A A A C R I Y N M L PA A R A P AD TE IS O E R P R I F 14 Swartland RIA O WYNBERG NU T C S I E V D CLAREMONT O H R D WOO BOW Drakenstein E OUDEKRAAL 14 D IN B U R G BISHOPSCOURT H RH T OD E ES N N A N Load-shedding 6 T KENILWORTH Area 11 Table Bay Atlantic 2 13 10 T Ocean R 1 O V 15 A Stellenbosch 7 9 T O 12 L 5 22 A WETTO W W N I 21 L 2S 3 A I A 11 M T E O R S L E N O D Hout Bay 16 4 O V 17 O A H 17 N I R N 17 A D 3 CONSTANTIA M E WYNBERG V R I S C LLANDUDNO T Theewaterskloof T E O 8 L Gordon's R CO L I N L A STA NT Bay I HOUT BAY IA H N ROCKLEY False E M H Bay P A L A I N MAI N IA Please Note: T IN N A G - Every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of information in this map at the time of puMblication . -

The Great Green Outdoors

MAMRE CITY OF CAPE TOWN WORLD DESIGN CAPITAL CAPE TOWN 2014 ATLANTIS World Design Capital (WDC) is a biannual honour awarded by the International Council for Societies of Industrial Design (ICSID), to one city across the globe, to show its commitment to using design as a social, cultural and economic development tool. THE GREAT Cape Town Green Map is proud to have been included in the WDC 2014 Bid Book, 2014 SILWERSTROOMSTRAND and played host to the International ICSID judges visiting the city. 01 Design-led thinking has the potential to improve life, which is why Cape WORLD DESIGN CAPITAL GREEN OUTDOORS R27 Town’s World Design Capital 2014’s over-arching theme is ‘Live Design. Transform Life.’ Cape Town is defi nitively Green by Design. Our city is one of a few Our particular focus has become ‘Green by Design’ - projects and in the world with a national park and two World Heritage Sites products where environmental, social and cultural impacts inform (Table Mountain National Park and Robben Island) contained within design and aim to transform life. KOEBERG NATURE its boundaries. The Mother City is located in a biodiversity hot Green Map System accepted Cape Town’s RESERVE spot‚ the Cape Floristic Region, and is recognised globally for its new category and icon, created by Design extraordinarily rich and diverse fauna and fl ora. Infestation – the fi rst addition since 2008 to their internationally recognised set of icons. N www.capetowngreenmap.co.za Discover and experience Cape Town’s natural beauty and enjoy its For an overview of Cape Town’s WDC 2014 projects go to www.capetowngreenmap.co.za/ great outdoor lifestyle choices. -

Activism in Manenberg, 1980 to 2010

Then and Now: Activism in Manenberg, 1980 to 2010 Julian A Jacobs (8805469) University of the Western Cape Supervisor: Prof Uma Dhupelia-Mesthrie Masters Research Essay in partial fulfillment of Masters of Arts Degree in History November 2010 DECLARATION I declare that „Then and Now: Activism in Manenberg, 1980 to 2010‟ is my own work and that all the sources I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. …………………………………… Julian Anthony Jacobs i ABSTRACT This is a study of activists from Manenberg, a township on the Cape Flats, Cape Town, South Africa and how they went about bringing change. It seeks to answer the question, how has activism changed in post-apartheid Manenberg as compared to the 1980s? The study analysed the politics of resistance in Manenberg placing it within the over arching mass defiance campaign in Greater Cape Town at the time and comparing the strategies used to mobilize residents in Manenberg in the 1980s to strategies used in the period of the 2000s. The thesis also focused on several key figures in Manenberg with a view to understanding what local conditions inspired them to activism. The use of biographies brought about a synoptic view into activists lives, their living conditions, their experiences of the apartheid regime, their brutal experience of apartheid and their resistance and strength against a system that was prepared to keep people on the outside. This study found that local living conditions motivated activism and became grounds for mobilising residents to make Manenberg a site of resistance. It was easy to mobilise residents on issues around rent increases, lack of resources, infrastructure and proper housing. -

South Africa and Cape Town 1985-1987

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. A Tale of Two Townships: Race, Class and the Changing Contours of Collective Action in the Cape Town Townships of Guguletu and Bonteheuwel, 1976 - 2006 Luke Staniland A Thesis Submitted in Fulfilment of the PhD University of Edinburgh 2011 i Declaration The author has been engaged in a Masters by research and PhD by research programme of full-time study in the Centre of African Studies under the supervision of Prof. Paul Nugent and Dr. Sarah Dorman from 2004-2011 at the University of Edinburgh. All the work herein, unless otherwise specifically stated, is the original work of the author. Luke Staniland. i ii Abstract This thesis examines the emergence and evolution of ‘progressive activism and organisation’ between 1976 and 2006 in the African township of Guguletu and the coloured township of Bonteheuwel within the City of Cape Town. -

PENINSULA MAP Visitor Information Centres Police Station WITSAND

MAMRE PELLA ATLANTIS Cape Town Tourism PENINSULA MAP Visitor Information Centres Police Station WITSAND R27 Transport Information Centre 0800 656 463 CAPE TOWN TOURISM SERVICES GENERAL TRAVEL INFORMATION: Champagne All you need to know about Cape Town P hila W d el Adam Tas e ph and travelling within the City. s i t a C Wellington o R302 a PHILADELPHIA s R304 t k KOEBERG M c RESERVATIONS: e You can do all your bookings via Cape Town Tourism a e l b m e i e R s Visitor Information Centres, online and via our Call Centre. b u an r V y n y a r J u Silwerstroom b SANPARKS BOOKINGS/SERVICES: s R304 Reservations, Activity Cards, Green e Main Beach lm a Cards & Permits at designated Visitor Information Centres. M ld DUYNEFONTEIN O R45 COMPUTICKET BOOKINGS: Book your Theatre, Events or Music Shows R312 at designated Visitor Information Centres. M19 Melkbosstrand N7 MELKBOSSTRAND R44 WEBTICKETS ONLINE BOOKINGS: Langenh Robben Island Trips, Kirstenbosch oven Concerts, Table Mountain Cable Car Trip at all Cape Town Tourism R304 PAARL M14 Visitor Information Centres. Suid Agter Paarl R302 R27 M58 CITY SIGHTSEEING HOP ON HOP OFF BUS TICKETS: Purchase your tickets Main West Coast at designated Visitor Information Centres. Otto Du Plessis l BLAAUWBERG e Lichtenberg w u e h p li Visse Adderley MYCITI BUS ROUTE SERVICE: Purchase and load your MyConnect Card rshok K N1 Big Bay BLOUBERGSTRAND at Cape Town International Airport and City Centre. Big Bay i le v West Coast M48 s on Marine m PARKLANDS Si m ROBBEN ISLAND a Wellington d ts o R302 KLAPMUTS TABLE -

AC097 FA Cape Town City Map.Indd

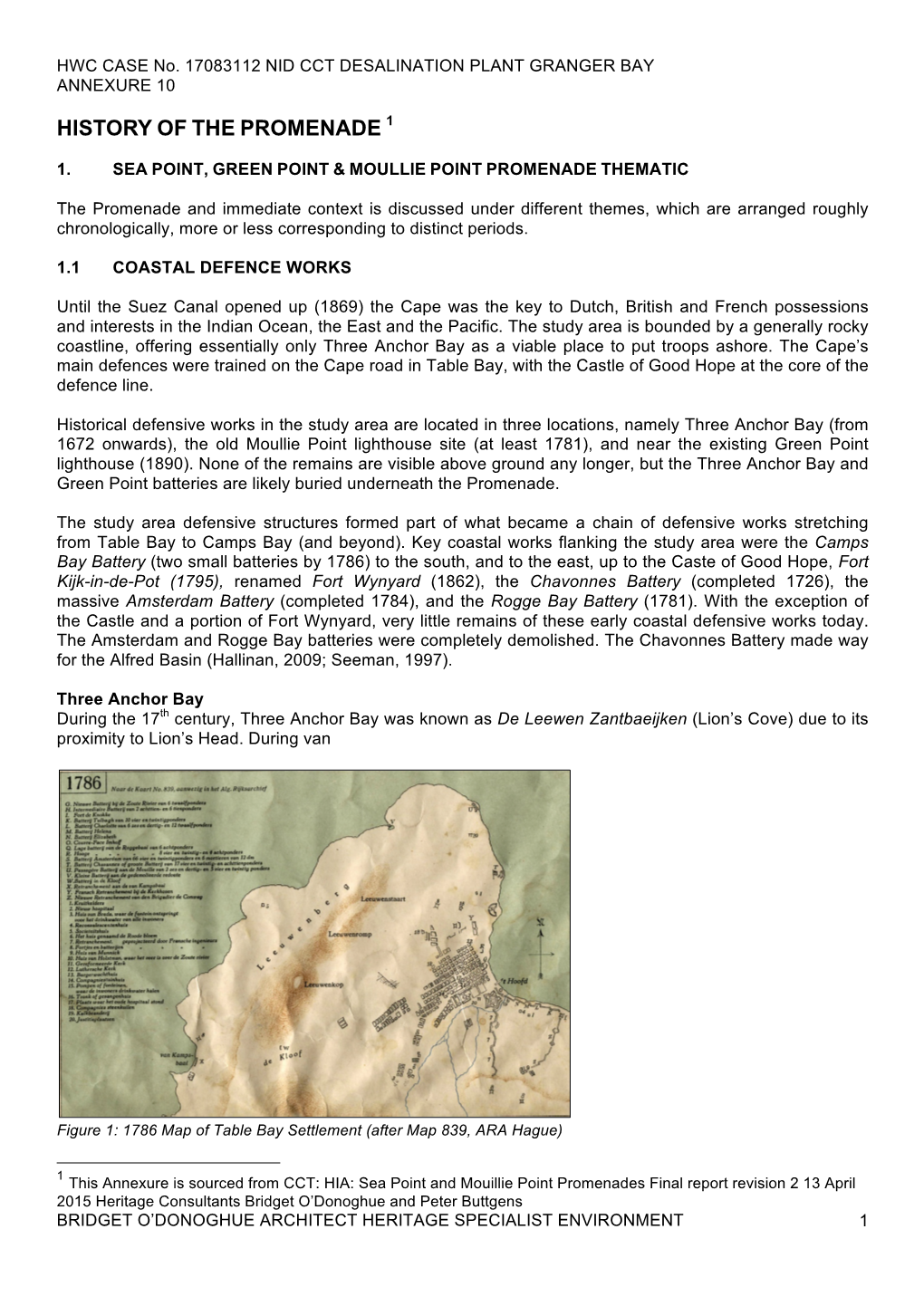

MAMRE 0 1 2 3 4 5 10 km PELLA ATLANTIS WITSAND R27 PHILADELPHIA R302 R304 KOEBERG R304 I CAME FOR DUYNEFONTEIN MAP R45 BEAUTIFULR312 M19 N7 MELKBOSSTRAND R44 LANDSCAPES,PAARL M14 R304 R302 R27 M58 AND I FOUND Blaauwberg BEAUTIFULN1 PEOPLE Big Bay BLOUBERGSTRAND M48 B6 ROBBEN ISLAND PARKLANDS R302 KLAPMUTS TABLE VIEW M13 JOOSTENBERG KILLARNEY DURBANVILLE VLAKTE City Centre GARDENS KRAAIFONTEIN N1 R44 Atlantic Seaboard Northern Suburbs SONSTRAAL M5 N7 Table Bay Sunset Beach R304 Peninsula R27 BOTHASIG KENRIDGE R101 M14 PLATTEKLOOF M15 Southern Suburbs M25 EDGEMEAD TYGER VALLEY MILNERTON SCOTTSDENE M16 M23 Cape Flats M8 BRACKENFELL Milnerton Lagoon N1 Mouille Point Granger Bay M5 Helderberg GREEN POINT ACACIA M25 BELLVILLE B6 WATERFRONT PARK GOODWOOD R304 Three Anchor Bay N1 R102 CAPE TOWN M7 PAROW M23 Northern Suburbs STADIUM PAARDEN KAYAMANDI SEA POINT EILAND R102 M12 MAITLAND RAVENSMEAD Blaauwberg Bantry Bay SALT RIVER M16 M16 ELSIESRIVIER CLIFTON OBSERVATORY M17 EPPING M10 City Centre KUILS RIVER STELLENBOSCH Clifton Bay LANGA INDUSTRIA M52 Cape Town Tourism RHODES R102 CAMPS BAY MEMORIAL BONTEHEUWEL MODDERDAM Visitor Information Centres MOWBRAY N2 R300 M62 B6 CABLE WAY ATHLONE BISHOP LAVIS M12 M12 M3 STADIUM CAPE TOWN TABLE MOUNTAIN M5 M22 INTERNATIONAL Police Station TABLE RONDEBOSCH ATHLONE AIRPORT BAKOVEN MOUNTAIN NATIONAL BELGRAVIA Koeël Bay PARK B6 NEWLANDS RYLANDS Hospital M4 CLAREMONT GUGULETU DELFT KIRSTENBOSCH M54 R310 Atlantic Seaboard BLUE DOWNS JAMESTOWN B6 Cape Town’s Big 6 M24 HANOVER NYANGA Oude Kraal KENILWORTH PARK