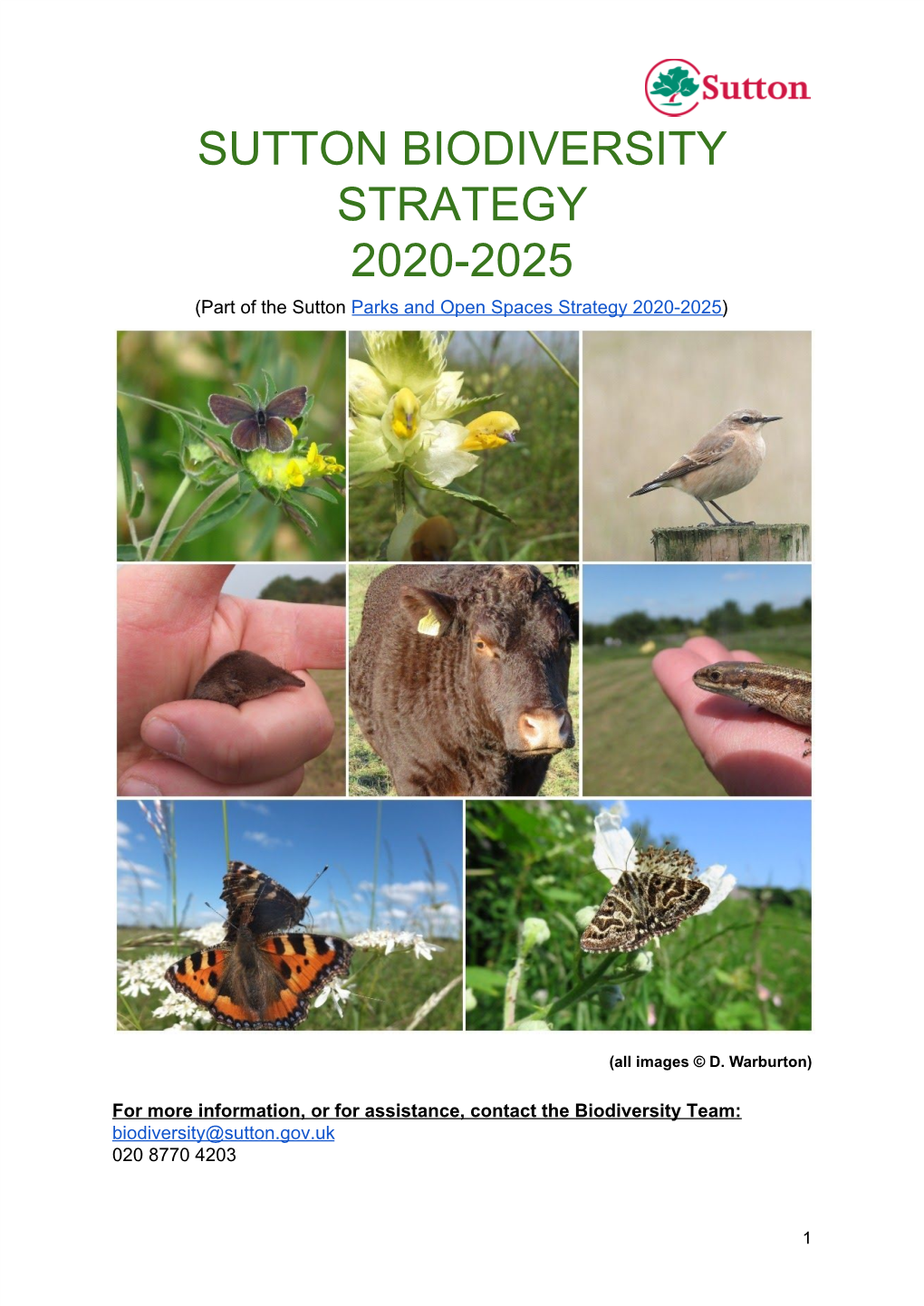

Sutton Biodiversity Strategy 2020-2025

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Foundations of the Wandle Trail

Wandle Industrial Museum Bulletin Issue 100 WANDLE Trail Special 2018 Contents Editorial The Foundations of the Welcome to this special edition of our Wandle Trail 3 bulletin to celebrate 30 years since the first ‘official ‘ Wandle Trail walk They Said What! 5 on 18th September 1988. Recalling a Recent Walk along the Wandle Trail 8 Looking through the pages you will learn about some of the earlier walks A History of Wandle Trail / that took place, what people have Heritage Maps and Guides 11 had to say about the trail and the Recalling a Recent Walk Along river, the maps that have been The Wandle Trail: produced since the first Wandle Trail Endnote and References 14 map, and what is happening on 16th September in celebration of the first Wandle Trail Anniversary Walks 15 walk. I hope that you will find this look back of interest. Best wishes, WANDLE INDUSTRIAL Mick Taylor MUSEUM Founded in 1983 PRESIDENT Harry Galley TRUSTEES Nicholas Hart John Hawks Fr David Pennells OPERATIONS COMMITTEE Alison Cousins Eric Shaw Roger Steele Michael Taylor Cover Picture: A book produced by the museum. This A4 GUEST EDITOR book produced in the late 1980s covered just Michael Taylor part of the Wandle Trail. Wandle Industrial Museum Bulletin The Foundations of the Wandle Trail The museum was founded in 1983. By 1984 it was producing guides and leading walks along parts of the Wandle. In August 1984 Stephen Ashcroft, at that time a trustee of the museum, wrote to the Local Guardian newspaper about the loss of historical materials from the arch in Station Road, Merton Abbey. -

Buses from North Cheam

Buses from North Cheam X26 Heathrow Terminals 2 & 3 93 Central Bus Station Putney Bridge River Thames Putney Hatton Cross PUTNEY Putney Heath Tibbet’s Corner Teddington Broad Street Wimbledon War Memorial River Thames 213 Kingston Wimbledon Kingston Faireld Bus Station Wood Street WIMBLEDON Norbiton Church KINGSTON South Wimbledon Kingston Hospital Kingston Morden Road Clarence Street Kenley Road The Triangle Hillcross Avenue Morden New Malden Lower Morden Lane Morden Cemetery 293 MORDEN NEW New Malden Fountain Morden South MALDEN Malden Road Motspur Park Hail & Ride Garth Road Rosebery Close section Epsom Road Rutland Drive MORDEN Malden Road Lyndhurst Drive Garth Road Browning Avenue Alpha Place Epsom Road Lower Morden Lane PARK Malden Road Plough Green Garth Road Stonecot Hill Stonecot Hill Sutton Common Road Hail & Ride Malden Road Dorchester Road Malden Green Green Lane section Stonecot Hill Burleigh Road Avenue S3 151 Langley Stonecot Hill Garth Road Malden Avenue Manor Central Road Longfellow Road Worcester Park St. Anthony’s Hospital Hail & Ride Manor Drive North Central Road Brabham Court section Hail & Ride The Cheam Common Road Lindsay Road section Manor Drive Staines Avenue Cheam Common Road London Road Langley Avenue Woodbine Lane Henley Avenue North Cheam Sports Club ST. HELIER Windsor Avenue Green C Wrythe Lane HE Kempton Road AM Thornton Road CO d RO M Sutton Cheam Tesco A MO [ Wrythe Green D N \ Z Oldelds Road Stayton Road St. Helier Hospital e Hail & Ride ] Wrythe Lane Sutton Common Road section K Sainsbury’s IN G The yellow tinted area includes every S Marlborough Road Hackbridge Corner M C St. -

Local Area Map Bus Map

Cheam Station – Zone 5 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 10 30 11 OSPREY4 FIELDSEND D CLOSE M S R ROAD R 2 B O U R N E WAY 262West Sutton A E 2 1 T 1 P I Homefield L P 31 PETERSHAM 2 . D Preparatory School D 51 N CLOSE A E 18 19 24 49 C O R M O R A S 45 D N T N E Y R O A P L A C E T E A L FROMONDES ROAD M L D P L L U A C E D 26 D A TUDOR CLOSE U O 16 Tennis R R R 8 K Courts 39 1 30 R R O E TAT E R O A D N A 45 P 6 P L 128 I 11 A U P Y ANTROBUS CLOSE 1 G 26 68 M D R WESTERN ROAD A N R D S A Sutton R L S A 28 E D 27 KITTIWAKE U 28 Y 171 T 71 E R Q Christian N U PLACE 36 66 T O S C E E Centre Playground B 12 R E A G N HEATHROW AIRPORT 69 29 4 N A LUMLEY ROAD N E Cheam Village 17 L L O V E L A Heathrow Terminals 1,2,3 TUDOR CLOSE Bowls Club ’ Colliers Wood 16 470 52 2 S Seears Park Central Bus Station Bowling N Green 37 X26 E 130 Playground 19 E E H CARLISLE ROAD N LANE Hatton Cross Merton Abbey Merantun Way T A 11 L SPRINGCLOSE R U S D E I O K O G R O 23 L C C Cheam Recreation 21 L 12 A D 12 Teddington Broad Street O O 9 NS R S R Café R DE St. -

Buses from Worcester Park

Buses from Worcester Park X26 Heathrow Terminals 1, 2, 3 Central Bus Station Hatton Cross Teddington Broad Street River Thames Kingston Wood Street Key Kingston 213 Clarence Street Kingston Ø— Connections with London Underground Fairfield Bus Station R Connections with National Rail KINGSTON Norbiton Church h Connections with Tramlink ✚ Mondays to Saturdays except evenings Kingston Hospital x Limited stop Clarence Avenue Dickerage Road/ The Triangle New Malden New Malden High Street A NEW MALDEN Red discs show the bus stop you need for your chosen bus !A New Malden service. The disc appears on the top of the bus stop in the Fountain 1 2 3 street (see map of town centre in centre of diagram). 4 5 6 New Malden St. JamesÕ Church/Kingston By-Pass H&R Routes E16 and S3 operate as hail and ride on the section Malden Road of road marked H&R on the map. Buses stop at any safe Blakes Lane point along the road. Malden Road Motspur Park Please indicate clearly to the driver when you wish to Browning Langley Staines board or alight. Malden Road Avenue Avenue Avenue South Lane Hail & Ride Dorchester X26 Malden Road section Road London Road Plough Langley Avenue Henley Avenue West Green Lane Croydon Malden Road Bus Station Malden Green Avenue North Cheam Hail & Ride Sports Club section Croydon S3 Windsor Avenue Wellesley Road Route finder WORCESTER PARK North Cheam CROYDON for Whitgift Centre Malden Manor STATION SainsburyÕs Hail & Ride M B H&R2 A D Day buses including 24-hour routes section LD A H&R1 C E E A Gander Green Lane East Manor Drive North N N O R A R E Croydon D L Bus route Towards Bus stops . -

London's Rail & Tube Services

A B C D E F G H Towards Towards Towards Towards Towards Hemel Hempstead Luton Airport Parkway Welwyn Garden City Hertford North Towards Stansted Airport Aylesbury Hertford East London’s Watford Junction ZONE ZONE Ware ZONE 9 ZONE 9 St Margarets 9 ZONE 8 Elstree & Borehamwood Hadley Wood Crews Hill ZONE Rye House Rail & Tube Amersham Chesham ZONE Watford High Street ZONE 6 8 Broxbourne 8 Bushey 7 ZONE ZONE Gordon Hill ZONE ZONE Cheshunt Epping New Barnet Cockfosters services ZONE Carpenders Park 7 8 7 6 Enfield Chase Watford ZONE High Barnet Theydon Bois 7 Theobalds Chalfont Oakwood Grove & Latimer 5 Grange Park Waltham Cross Debden ZONE ZONE ZONE ZONE Croxley Hatch End Totteridge & Whetstone Enfield Turkey Towards Southgate Town Street Loughton 6 7 8 9 1 Chorleywood Oakleigh Park Enfield Lock 1 High Winchmore Hill Southbury Towards Wycombe Rickmansworth Moor Park Woodside Park Arnos Grove Chelmsford Brimsdown Buckhurst Hill ZONE and Southend Headstone Lane Edgware Palmers Green Bush Hill Park Chingford Northwood ZONE Mill Hill Broadway West Ruislip Stanmore West Finchley Bounds 5 Green Ponders End Northwood New Southgate Shenfield Hillingdon Hills 4 Edmonton Green Roding Valley Chigwell Harrow & Wealdstone Canons Park Bowes Park Highams Park Ruislip Mill Hill East Angel Road Uxbridge Ickenham Burnt Oak Key to lines and symbols Pinner Silver Street Brentwood Ruislip Queensbury Woodford Manor Wood Green Grange Hill Finchley Central Alexandra Palace Wood Street ZONE North Harrow Kenton Colindale White Hart Lane Northumberland Bakerloo Eastcote -

Public Consultation on the Draft Hackbridge Masterplan

Summary Report on Public Consultation on the draft Hackbridge Masterplan London Borough of Sutton May 2009 Draft Hackbridge Masterplan Public Consultation -Summary Report Contents 1. Introduction 2. Consultation Process 3. Consultation Response 4. Public Exhibition 5. Community Workshop 6. Questionnaire Response 7. Summary of Key Comments • Statutory Consultees • Landowners • District Centre & local facilities • Building Heights • Land North of BedZED • Infrastructure • Housing • Education • Employment • Environment • Biodiversity • Green Spaces • Heritage 8. Next Stages 2 Draft Hackbridge Masterplan Public Consultation -Summary Report 1. Introduction This report provides a summary of the consultation process and the key points/ comments received during the public consultation on the draft Hackbridge Masterplan. Officers comments and considerations are also included. The consultation responses will assist the Council in developing its approach towards future plans for Hackbridge as a sustainable suburb. The draft Hackbridge Masterplan builds on feedback received from public consultation over the last 3 years on how Hackbridge can become a sustainable neighbourhood, including consultation on the ‘Draft Hackbridge Supplementary Planning Document- Towards a Sustainable Suburb: Issues and Options’ in October 2006, a ‘One Planet Living’ Review in April 2007, Developers’ Panel in June 2007, Hackbridge Week in February 2008 and Stakeholder Workshops in September 2008. The preparation of the draft Masterplan following the above consultations has assisted in informing policies put forward for Hackbridge in the Core Planning Strategy and Site Development Policies. The consultation feedback on the draft Masterplan, together with further detailed studies and considerations will eventually feed into the preparation of a Hackbridge Supplementary Planning Document, providing detailed planning guidance on the future development and delivery of the Hackbridge ‘Sustainable Suburb’. -

LBR 2007 Front Matter V5.1

1 London Bird Report No.72 for the year 2007 Accounts of birds recorded within a 20-mile radius of St Paul's Cathedral A London Natural History Society Publication Published April 2011 2 LONDON BIRD REPORT NO. 72 FOR 2007 3 London Bird Report for 2007 produced by the LBR Editorial Board Contents Introduction and Acknowledgements – Pete Lambert 5 Rarities Committee, Recorders and LBR Editors 7 Recording Arrangements 8 Map of the Area and Gazetteer of Sites 9 Review of the Year 2007 – Pete Lambert 16 Contributors to the Systematic List 22 Birds of the London Area 2007 30 Swans to Shelduck – Des McKenzie Dabbling Ducks – David Callahan Diving Ducks – Roy Beddard Gamebirds – Richard Arnold and Rebecca Harmsworth Divers to Shag – Ian Woodward Herons – Gareth Richards Raptors – Andrew Moon Rails – Richard Arnold and Rebecca Harmsworth Waders – Roy Woodward and Tim Harris Skuas to Gulls – Andrew Gardener Terns to Cuckoo – Surender Sharma Owls to Woodpeckers – Mark Pearson Larks to Waxwing – Sean Huggins Wren to Thrushes – Martin Shepherd Warblers – Alan Lewis Crests to Treecreeper – Jonathan Lethbridge Penduline Tit to Sparrows – Jan Hewlett Finches – Angela Linnell Buntings – Bob Watts Appendix I & II: Escapes & Hybrids – Martin Grounds Appendix III: Non-proven and Non-submitted Records First and Last Dates of Regular Migrants, 2007 170 Ringing Report for 2007 – Roger Taylor 171 Breeding Bird Survey in London, 2007 – Ian Woodward 181 Cannon Hill Common Update – Ron Kettle 183 The establishment of breeding Common Buzzards – Peter Oliver 199 -

Page 11 Agenda Item 6

Page 11 Agenda Item 6 London Borough of Sutton Beddington and Wallington Area Committee – 7 March 2007 Sutton Area Committee – 21 March 2007 Carshalton and Clockhouse Area Committee – 4 April 2007 Cheam and Worcester Park Area Committee – 18 April 2007 Report of the Traffic and Highway Works Manager LOCAL IMPLEMENTATION PLAN FUNDING 2007/2008 TRANSPORT SETTLEMENT Ward Location: Not Applicable Author(s) and Contact Phone Numbers: Area Served: Borough-Wide Paul Blunt 020 8770 6445 Lead Councillor: Councillor Colin Hall Executive Decision Report Summary The Council has been advised by Transport for London (TfL) of the Local Implementation Plan (LIP) Funding for 2007/08. Sutton has been allocated a grant of £4,566,500 for 2007/8, plus £48,500 from SWELTRAC towards transport schemes. £403,000 is also allocated for ongoing schemes into 2008/09 and £83,000 in 2009/10. Recommendations I recommend the Committee to: a. Note the 2007/08 LIP funding settlement and the programme for which TfL has agreed the grant. b. Agree the list of schemes relevant to this Area committee. c. Delegate to the Executive Head Planning & Transportation, in consultation with the Chair and Ward Councillors to agree details of individual schemes. 1. Background 1.1 Following the report to this Committee in July 2006, the Council submitted its Local Implementation Plan Reporting and Funding Submission (LIP RFS) for 2007/8 to TfL last July in accordance with guidance issued earlier in the year. The LIP RFS system is used as a basis for allocating capital funding to London local authorities for roads, transport, traffic and other highway related matters. -

Volunteering Task Details

Sutton Nature Conservation Volunteers Task Programme July 2016 to October 2016 To book on events, use the online portal: http://37.188.117.158/suttonecology/ or for directions to events, look on the website http://suttonnature.wordpress.com/events/ or e-mail: [email protected] (Mon to Fri) Call 020 8770 5821 or email [email protected] for additional information about SNCV work Don’t forget tasks are held at Sutton Ecology Centre on Wednesdays - 10 - 4pm! Task programmes & newsletters here Weekend Tasks https://suttonnature.wordpress.com/task- programme/ Spencer Road Wetland Tasks take place on the first Saturday of the month from 11:00 to 1:30. Meet by the reserve entrance Sutton Biodiversity Events for 2016 gate on Spencer Road, Mitcham Junction. Task leader is Norman Jones - 020 8286 1874 / email: http://suttonnature.wordpress.com/events/ [email protected] Carew Manor Wetland Tasks take place on the second Sunday of the Task Details month. Meet at 10:15 in the second car park behind the cottages in Beddington Park, near the Wildlife Hospital (end of Church Road). Task leader is Ron Kriehn - 020 8395 7231/ email: Midweek tasks run from 10:00 to 16:00. [email protected] If you require a lift, please meet at the Ecology Centre at 09:40 in order to help load tools and Sutton Ecology Centre equipment into the minibus. Takes place every Wednesday from 10:45 until 16:00 (except the 1st Wednesday of the month) and on the You are also welcome to join us on site but you 3rd Sunday of the month from 10:00 - 14:00. -

Diary September 2018.Rtf

Diary September 2018 Sat 1 Lambeth Local History Fair Omnibus, 1 Clapham Common North Side, SW4, 10.15am–4.15pm (to 30) Lambeth Heritage Festival Month LHF: West Norwood Cemetery’s Clapham Connections, Omnibus Theatre, SW4, 10.45am National Trust: Quacky Races on the Wandle, Snuff Mill, Morden Hall Park, 11am-3pm LWT: Great North Wood Walk, Great North Wood team, Sydenham Hill station, College Rd, noon LHF: Rink Mania in Edwardian Lambeth, Sean Creighton, Omnibus Theatre, SW4, 12.30pm LHF: Clapham Library to Omnibus Theatre, Peter Jefferson Smith & Marie McCarthy, 1.30pm Godstonebury Festival, Orpheus Centre, North Park Lane, Godstone, 12-8pm SCOG: 36 George Lane, Hayes, BR2 7LQ, 2-8pm Laurel and Hardy Society: The Live Ghost Tent, Cinema Musum, 3pm LHF: 1848 Kennington Common Chartists’ Rally, Marietta Crichton Stuart & Richard Galpin, 3.15pm Sun 2 NGS: Royal Trinity Hospice, 30 Clapham Common North Side, 10am-4.30pm Streatham’s Art-Deco & Modernism Walk, Adrian Whittle, Streatham Library, 10.30am Streatham Kite Day, Streatham Common, 11am-5pm Historic Croydon Airport Trust: Open Day, 11am-4pm Shirley Windmill: Open Day, Postmill Close, Croydon, 12-5pm Crystal Palace Museum: Guided tour of the historic Crystal Palace grounds, noon Streatham Society: Henry Tate Gardens Tour, Lodge gates, Henry Tate Mews, SW16, 2 & 3pm NGS: 24 Grove Park, Camberwell, SE5 8LH, 2-5.30pm Kennington Talkies: After the Thin Man (U|1936|USA|110 min), Cinema Musum, 2.30pm Herne Hill S'y: South Herne Hill Heritage Trail, Robert Holden, All Saints’ Ch, Lovelace -

London Borough of Sutton Byelaws for Pleasure

Appendix A LONDON BOROUGH OF SUTTON BYELAWS FOR PLEASURE GROUNDS, PUBLIC WALKS AND OPEN SPACES ARRANGEMENT OF BYELAWS PART 1 GENERAL 1. General Interpretation 2. Application 3. Opening times PART 2 PROTECTION OF THE GROUND, ITS WILDLIFE AND THE PUBLIC 4. Protection of structures and plants 5. Unauthorised erection of structures 6. Affixing of signs 7. Climbing 8. Grazing 9. Protection of wildlife 10. Gates 11. Camping 12. Fires 13. Missiles 14. Interference with life-saving equipment PART 3 HORSES, CYCLES AND VEHICLES 15. Interpretation of Part 3 16. Horses 17. Cycling 18. Motor vehicles 19. Overnight parking PART 4 PLAY AREAS, GAMES AND SPORTS 20. Interpretation of Part 4 21. Children’s play areas 22. Children’s play apparatus 23. Skateboarding Etc. 24. Ball games 25. Cricket 26. Archery 27. Field Sports 28. Golf PART 5 WATERWAYS 29. Interpretation of Part 5 30. Bathing 31. Ice Skating 32. Model Boats 33. Boats 34. Fishing 35. Pollution of waterways 36. Blocking of watercourses PART 6 MODEL AIRCRAFT 37. Interpretation of Part 6 38. General prohibition 39. Use permitted in certain grounds PART 7 OTHER REGULATED ACTIVITIES 40. Trading 41. Excessive noise 42. Public shows and performances 43. Aircraft, hand-gliders and hot-air balloons 44. Kites 45. Metal detectors PART 8 MISCELLANEOUS 46. Obstruction 47. Savings 48. Removal of offenders 49. Penalty 50. Revocation SCHEDULE 1 List of Grounds PART 1 PART 2 PART 3 SCHEDULE 2 Rules for Playing Ball Games in Designated Areas Byelaws made under section 164 of the Public Health Act 1875, section 15 of the Open Spaces Act 1906 and sections 12 and 15 of the Open Spaces Act 1906 by the Council of the London Borough Of Sutton with respect to the pleasure grounds, public walks and open spaces referred to in Schedule 1 to these byelaws. -

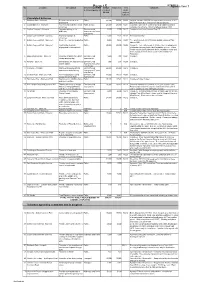

Area Improvements Appendix.Pdf

APPENDIX A No Location Description Service/OrganisatioPage 15Budget Final cost Cost Comments Agenda Item 7 n delivering project released code/ £0=N/K project referenc e Completed Schemes 1 Fairlands Park - Nonsuch Relocate and install new Parks 60,000 65,531 M200 Original estimate £60,000, overspend due to amount of wet playground pour that had to be removed from old playground. 2 Cuddington Rec - Nonsuch New fencing at all three main Parks Service 28,000 28,000 M201 Committee agreed 18.12.08 to spend an additional £8k to entrances complete this scheme. Work completed August 2009 3 Carlton Crescent - Nonsuch Upgrade lighting to the Environmental 3,000 3,000 M217 Complete, cost to be finalised Sept 10 bridleway Improvement/Comm unity Safety 4 Sutton Common Park - Stonecot Improved signage at Parks 2,000 1,402 M202 New sign installed. entrances 5 Sutton Common Park - Stonecot Flower tree and shrub planting Parks 5,000 5,464 M203 Tree planting cost of £1370; bulbs £2000; shrubs £1794; labour £300. 6 Sutton Common Park - Stonecot Contribution towards Parks 25,000 25,000 M204 Complete. Agreed to complete at same time as playground playground / climbing frame refurbishment being funded by Playbuilder scheme. Public Realm contribution funded new fence, installation costs and infant swings as these items could not be funded from Playbuilder. 9 Ridge Road Library - Stonecot Provision of plants for FORR Environmental 1,000 703 M207 Complete Library planting day Improvement 10 Kimpton - Stonecot SNT Signage (Neighbourhood Environmental 300 279 M208 Complete Watch Signs) Improvement/Comm unity Safety 11 Stonecot - All Ward Improved alleyway lighting Environmental 20,000 20,000 M216 Complete.