Parks and Open Spaces Strategy 2019-2026

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Environment Act 1995 Contaminated Land Strategy for the London Borough of Croydon

Environment Act 1995 Contaminated Land Strategy for the London Borough of Croydon London Borough of Croydon Community Services Department Regulatory Services Taberner House Park Lane Croydon CR9 3BT Revision Compiled by: Rebecca Emmett Pollution Team www.croydon.gov.uk i CONTENTS PAGE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY INTRODUCTION 1 Introduction 1 Background 1 The Implementation of Part IIA & Legal Framework 1 Croydon Council Objectives under the Regime 1 Definition of Contaminated Land 2 Interaction with Planning Controls 4 Interaction with other Regimes 5 CHARACTERISTICS OF THE BOROUGH OF CROYDON 7 Introduction 7 Historic Land Uses 7 Current Land Uses 7 Solid and Drift Geology 7 Surface Waters 8 Hydrogeology & Groundwater Vulnerability 8 Known Information on Contamination 9 INITIAL STAGES OF THE STRATEGY 10 Strategic Approach to Inspection 10 Geographical Information Systems (GIS) Approach 10 Sourcing Sites of Potential Contamination 10 Ward/Kelly’s Street Directories 11 Other Sources of Information 13 Sourcing Sites for Potential Receptors 13 Functions of BGS 15 A Risk Based Model 15 The Prioritisation of Efforts 16 Appraisal of the Risk Based Model 17 Radioactive Contaminated Land 17 OTHER SOURCES OF INFORMATION AT PRESENT NOT AVAILABLE TO THE COUNCIL 18 Complaints from the Public, NGO’s and Businesses 18 IPPC Baseline Investigations 18 Pre-Acquisition Investigations 18 PROCEDURES TO BE PUT IN PLACE ONCE POTENTIALLY CONTAMINATED SITES HAVE BEEN IDENTIFIED 19 Introduction 19 Stage 1: Initial Desktop Investigation 19 Stage 2: Site Walkover 20 Stage -

Walk and Cycleroute

Wandsworth N Bridge Road 44 TToo WaterlooWaterloo Good Cycling Code Way Wandsworth River Wandle On all routes… Swandon Town Walk and Cycle Route The Thames Please be courteous! Always cycle with respect Thames Road 37 39 87 www.wandletrail.org Cycle Route Ferrier Street Fairfield Street for others, whether other cyclists, pedestrians, NCN Route 4 Old York 156 170 337 Enterprise Way Causeway people in wheelchairs, horse riders or drivers, to Richmond Ram St. P and acknowledge those who give way to you. Osiers RoadWandsworth EastWWandsworth Hillandsworth Plain Wandle Trail Wandle Trail Connection Proposed Borough Links to the Toilets Disabled Toilet Parking Public Public Refreshments Seating Tram Stop Street MMuseumuseum for Walkers for Walkers to the Trail Future Route Boundary London Cycling Telephone House On shared paths… High Garratt & Cyclists Network Key to map ●Give way to pedestrians, giving them plenty Armoury Way 28 220 270 of room 220 270 B Neville u Lane WANDLE PARK TO PLOUGH LANE MERTON ABBEY MILLS TO MORDEN HALL PARK TO MERTON Wandsworth c ❿ ❾ ❽ ●Keep to your side of the dividing line, k Gill 44 270 h (1.56km, 21 mins) WANDLE PARK (Merton) ABBEY MILLS (1.76km, 25 mins) Close Road ❿ ❾ if appropriate ol d R (0.78km, 11 mins) 37 170 o Mapleton along Bygrove Road, cross the bridge over the Follow the avenue of trees through the park. Cross ●Be prepared to slow down or stop if necessary ad P King Garratt Lane river, along the path. When you reach the next When you reach Merantun Way cross at the the bridge over the main river channel. -

The Foundations of the Wandle Trail

Wandle Industrial Museum Bulletin Issue 100 WANDLE Trail Special 2018 Contents Editorial The Foundations of the Welcome to this special edition of our Wandle Trail 3 bulletin to celebrate 30 years since the first ‘official ‘ Wandle Trail walk They Said What! 5 on 18th September 1988. Recalling a Recent Walk along the Wandle Trail 8 Looking through the pages you will learn about some of the earlier walks A History of Wandle Trail / that took place, what people have Heritage Maps and Guides 11 had to say about the trail and the Recalling a Recent Walk Along river, the maps that have been The Wandle Trail: produced since the first Wandle Trail Endnote and References 14 map, and what is happening on 16th September in celebration of the first Wandle Trail Anniversary Walks 15 walk. I hope that you will find this look back of interest. Best wishes, WANDLE INDUSTRIAL Mick Taylor MUSEUM Founded in 1983 PRESIDENT Harry Galley TRUSTEES Nicholas Hart John Hawks Fr David Pennells OPERATIONS COMMITTEE Alison Cousins Eric Shaw Roger Steele Michael Taylor Cover Picture: A book produced by the museum. This A4 GUEST EDITOR book produced in the late 1980s covered just Michael Taylor part of the Wandle Trail. Wandle Industrial Museum Bulletin The Foundations of the Wandle Trail The museum was founded in 1983. By 1984 it was producing guides and leading walks along parts of the Wandle. In August 1984 Stephen Ashcroft, at that time a trustee of the museum, wrote to the Local Guardian newspaper about the loss of historical materials from the arch in Station Road, Merton Abbey. -

Buses from North Cheam

Buses from North Cheam X26 Heathrow Terminals 2 & 3 93 Central Bus Station Putney Bridge River Thames Putney Hatton Cross PUTNEY Putney Heath Tibbet’s Corner Teddington Broad Street Wimbledon War Memorial River Thames 213 Kingston Wimbledon Kingston Faireld Bus Station Wood Street WIMBLEDON Norbiton Church KINGSTON South Wimbledon Kingston Hospital Kingston Morden Road Clarence Street Kenley Road The Triangle Hillcross Avenue Morden New Malden Lower Morden Lane Morden Cemetery 293 MORDEN NEW New Malden Fountain Morden South MALDEN Malden Road Motspur Park Hail & Ride Garth Road Rosebery Close section Epsom Road Rutland Drive MORDEN Malden Road Lyndhurst Drive Garth Road Browning Avenue Alpha Place Epsom Road Lower Morden Lane PARK Malden Road Plough Green Garth Road Stonecot Hill Stonecot Hill Sutton Common Road Hail & Ride Malden Road Dorchester Road Malden Green Green Lane section Stonecot Hill Burleigh Road Avenue S3 151 Langley Stonecot Hill Garth Road Malden Avenue Manor Central Road Longfellow Road Worcester Park St. Anthony’s Hospital Hail & Ride Manor Drive North Central Road Brabham Court section Hail & Ride The Cheam Common Road Lindsay Road section Manor Drive Staines Avenue Cheam Common Road London Road Langley Avenue Woodbine Lane Henley Avenue North Cheam Sports Club ST. HELIER Windsor Avenue Green C Wrythe Lane HE Kempton Road AM Thornton Road CO d RO M Sutton Cheam Tesco A MO [ Wrythe Green D N \ Z Oldelds Road Stayton Road St. Helier Hospital e Hail & Ride ] Wrythe Lane Sutton Common Road section K Sainsbury’s IN G The yellow tinted area includes every S Marlborough Road Hackbridge Corner M C St. -

Welcome to the Summer 2020 Beddington Energy Recovery Facility (ERF) Construction Newsletter. Aerial Photograph of the Beddington Farmlands (Looking South)

Summer 2020 Beddington Community Newsletter Welcome to the summer 2020 Beddington Energy Recovery Facility (ERF) construction newsletter. Aerial photograph of the Beddington Farmlands (looking south). A lot has happened Speaking of wildlife, one of the most At Beddington, our combined heat and recent activities on-site was to install power plant feeds enough electricity on-site since the swift nesting boxes on the side of the into the National Grid to power 57,000 energy recovery facility. last edition of the homes. The facility will also soon start newsletter. The administration building at the delivering low-carbon heating and hot ERF has a brown living roof and will water supplies to the New Mill Quarter Viridor has now formally taken provide a habitat for swifts to feed development in Hackbridge as part control of the Beddington on before making their homes in the of the Sutton Decentralised Energy Energy Recovery Facility from its nesting boxes on the north-facing Network (SDEN). The highly insulated construction partners, who remain side of the building. pipelines from the ERF to New Mill on-site to finish the last components Quarter have been installed and are of the construction project. This marks On the wider Beddington Farmlands now being tested. a significant milestone in the project, (the green space stretching from and we are now completing the final Beddington Park to Mitcham Common) construction activities including there is plenty of activity planned as COVID-19 update wildlife habitats continue to be created, putting the finishing touches to the Viridor staff, including those with Viridor delivering the Beddington administration building and completing based at Beddington ERF, Restoration Management Plan to the roads around the facility. -

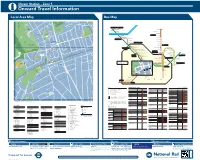

Local Area Map Bus Map

Cheam Station – Zone 5 i Onward Travel Information Local Area Map Bus Map 10 30 11 OSPREY4 FIELDSEND D CLOSE M S R ROAD R 2 B O U R N E WAY 262West Sutton A E 2 1 T 1 P I Homefield L P 31 PETERSHAM 2 . D Preparatory School D 51 N CLOSE A E 18 19 24 49 C O R M O R A S 45 D N T N E Y R O A P L A C E T E A L FROMONDES ROAD M L D P L L U A C E D 26 D A TUDOR CLOSE U O 16 Tennis R R R 8 K Courts 39 1 30 R R O E TAT E R O A D N A 45 P 6 P L 128 I 11 A U P Y ANTROBUS CLOSE 1 G 26 68 M D R WESTERN ROAD A N R D S A Sutton R L S A 28 E D 27 KITTIWAKE U 28 Y 171 T 71 E R Q Christian N U PLACE 36 66 T O S C E E Centre Playground B 12 R E A G N HEATHROW AIRPORT 69 29 4 N A LUMLEY ROAD N E Cheam Village 17 L L O V E L A Heathrow Terminals 1,2,3 TUDOR CLOSE Bowls Club ’ Colliers Wood 16 470 52 2 S Seears Park Central Bus Station Bowling N Green 37 X26 E 130 Playground 19 E E H CARLISLE ROAD N LANE Hatton Cross Merton Abbey Merantun Way T A 11 L SPRINGCLOSE R U S D E I O K O G R O 23 L C C Cheam Recreation 21 L 12 A D 12 Teddington Broad Street O O 9 NS R S R Café R DE St. -

London National Park City Week 2018

London National Park City Week 2018 Saturday 21 July – Sunday 29 July www.london.gov.uk/national-park-city-week Share your experiences using #NationalParkCity SATURDAY JULY 21 All day events InspiralLondon DayNight Trail Relay, 12 am – 12am Theme: Arts in Parks Meet at Kings Cross Square - Spindle Sculpture by Henry Moore - Start of InspiralLondon Metropolitan Trail, N1C 4DE (at midnight or join us along the route) Come and experience London as a National Park City day and night at this relay walk of InspiralLondon Metropolitan Trail. Join a team of artists and inspirallers as they walk non-stop for 48 hours to cover the first six parts of this 36- section walk. There are designated points where you can pick up the trail, with walks from one mile to eight miles plus. Visit InspiralLondon to find out more. The Crofton Park Railway Garden Sensory-Learning Themed Garden, 10am- 5:30pm Theme: Look & learn Crofton Park Railway Garden, Marnock Road, SE4 1AZ The railway garden opens its doors to showcase its plans for creating a 'sensory-learning' themed garden. Drop in at any time on the day to explore the garden, the landscaping plans, the various stalls or join one of the workshops. Free event, just turn up. Find out more on Crofton Park Railway Garden Brockley Tree Peaks Trail, 10am - 5:30pm Theme: Day walk & talk Crofton Park Railway Garden, Marnock Road, London, SE4 1AZ Collect your map and discount voucher before heading off to explore the wider Brockley area along a five-mile circular walk. The route will take you through the valley of the River Ravensbourne at Ladywell Fields and to the peaks of Blythe Hill Fields, Hilly Fields, One Tree Hill for the best views across London! You’ll find loads of great places to enjoy food and drink along the way and independent shops to explore (with some offering ten per cent for visitors on the day with your voucher). -

Melanie's Spring/Summer Walks 2016 Date Meeting Place/Time Walk

Melanie’s Spring/Summer Walks 2016 Date Meeting Walk description place/time Sat 5 Carshalton Wandle Walk to include Wilderness Island, Grove Park and Carshalton Park. 3-4 miles, Mar Station 2.15 pm easy. Tea at Honeywood Heritage Museum at end. Fri 25 St Mary’s Church A walk from Beddington Park to Mitcham Common. We will take the path along the March 10 am Beddington Farmlands path (about 45 mins and could be muddy). 2-3 miles, easy, but one (Good (see below) stile! Refreshments available at Mitcham Golf Club. £2 tea/coffee/cake. Return to St Friday) Mary’s Church afterwards or public transport from Mitcham Junction. Must be booked in advance. Please call or email to book. Sat 30 Carshalton Wandle Trail walk from Carshalton to Mitcham with a visit to Wilderness Island and April Station 2 pm Mitcham Common. 3-4 miles, easy. Drink at Mitcham Golf Club to finish. Sun 22 Mitcham Junction Mitcham Common walk. 3-4 miles, easy. Drink at Mitcham Golf Club to finish. May 3 pm Sat 4 Church Road Walk along the Wandle Trail. Finish 1.00 pm in Morden Hall Park (Phipps Bridge Tram June Tram Stop, Stop). 6 miles, easy. Coffee stop in Beddington Park or Carshalton. Part of an all day Croydon event between Waddon Ponds and Wandsworth, more start and finish options available. 9.10 am See the Sutton & Wandle Valley Ramblers’ website for details. For all walks starting at Mitcham Junction meet at bus stop on bridge. Sutton Healthy Walks - Come and join us for an hour’s walk around Beddington Park or Waddon Ponds every Friday morning at 10 am. -

Trees and the Public Realm (Draft)

TITLE PAGE _ FOR PAGINATION PURPOSES ONLY Page 2 Trees and the Public Realm (Draft) Document title: Trees and the Public Realm (Formal Consultation Draft) Version: Public consultation draft Date: January 2011 Produced by: City of Westminster City Planning Delivery Unit City Hall, 64 Victoria Street London SW1E 6QP Contact: Rebecca Cloke email [email protected] 020 7641 3433 Fax: 020 7641 3050 The cover image was sourced from maps.live.com Trees and the Public Realm (Draft) Page 3 CONTENTS Foreword…………………………………………………………………….………. …...…..5 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………………. .………7 2. Purpose and Aims…………………………………………………………..…….…9 3. The Value of Trees…………………………………………………………. ……...11 4. Westminster’s Townscape………………………………………………… ……...15 5. Urban Design Principles…………………………………………………………...21 6. Practical Site Considerations……………………………………………… ……...27 7. Species Selection…………………………………………………………...……...35 8. Sustainability Considerations……………………………………………………...41 9. Implementation……………...……………………………………………………...50 Appendices A. Great Trees of London B. Townscape Areas and Planting Principles C. Minimum Streetscape Standards for Tree Planting D. Commonly Used Species in Westminster E. Policy Framework F. Trees on Other Sites Which Affect the Public Realm F. References and Contacts Page 4 Trees and the Public Realm (Draft) Victoria Embankment Gardens (sourced from maps.live.com). Trees and the Public Realm (Draft) Page 5 Foreword The City of Westminster lies at the heart of the nation’s capital and its trees in the public realm make a significant contribution to London’s reputation as one of the world’s greenest cities. Beyond aesthetics, trees also make environmental contributions to our city – they sequester carbon dioxide and release oxygen, shade buildings and streets, and provide a psychological link to nature by signifying the change in seasons and the passage of time. -

Angler's Guide

An Angler’s Guide to the River Wandle In memory of Jed Edge - a fine fisherman and great friend of the Wandle. ISBN 978-1-78808-485-7 John O’Brien with expert input from Theo Pike, Jason Hill and Stewart Ridgway. January 2018 Fun for all - photo by Duncan Soar. 9 781788 084857 RRP £5.00 © Author John O’Brien. All rights reserved. Produced by STR Design & Print Limited www.str.uk.com An Angler’s Guide to the River Wandle Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................3 CATCH AND RELEASE – FISHING WITH CARE ...........................................4 GEOGRAPHY AND MAIN FEATURES ................................................................5 The headwaters ...................................................................................................................7 The main chalk stream .......................................................................................................7 The middle river .................................................................................................................8 The lower river ...................................................................................................................8 WHAT FISH ARE IN THE RIVER? .......................................................................9 A GUIDE TO FISHING THE RIVER ..................................................................10 THE HEADWATERS .................................................................................................12 -

Mapping the Mills: Places of Historic Interest Historic Mills & Works

Walks & Guide Walk One Mapping the Mills: High Street Carshalton to Hackbridge Discover the River Wandle’s This walk celebrates the power of water On West Street overlooking Carshalton Ponds To the south of Wilderness Island, above Industrial Heritage within the historic industries of the sits the Honeywood Museum (C). Grade II listed Butter Hill Bridge, stood the Calico Works River Wandle. with restored period features, the house was built Carshalton (14) built by George Ansell c.1782. Start: Coach and Horses Pub Carshalton across the outflow from a line of springs, possibly (Carshalton Station, Buses: 127, 157, to provide a cold bath, a popular cure-for-all Just south of the Bridge was Lower Mill 407, X26) during the 17th and 18th centuries. Nearby, the (12), dating from 1235 it milled corn for End: Hackbridge Carshalton Water Tower (D) dating from c.1715, its first 400 years. From 1650 it produced Grove Mill (30) and Crown Mill (29) (Hackbridge Station, Buses: 80, 127, 151) can be found. gunpowder, then copper, calico and paper before its closure in 1927. Distance: 1.5 miles In the grounds of The Grove a waterwheel and Duration: 1.5 hrs millstone belonging to Upper Mill (9) are still Upstream sat Hackbridge Mills (15), a visible. Listed in the Domesday Book 1086, group of three with multiple uses over time High Street Mill (8) was located on the site of the mill was used for grinding corn for many including fulling, dye, gunpowder and copper the present Coach and Horses Pub, originally centuries, but by 1895 it had been rebuilt and making. -

Public Consultation on the Draft Hackbridge Masterplan

Summary Report on Public Consultation on the draft Hackbridge Masterplan London Borough of Sutton May 2009 Draft Hackbridge Masterplan Public Consultation -Summary Report Contents 1. Introduction 2. Consultation Process 3. Consultation Response 4. Public Exhibition 5. Community Workshop 6. Questionnaire Response 7. Summary of Key Comments • Statutory Consultees • Landowners • District Centre & local facilities • Building Heights • Land North of BedZED • Infrastructure • Housing • Education • Employment • Environment • Biodiversity • Green Spaces • Heritage 8. Next Stages 2 Draft Hackbridge Masterplan Public Consultation -Summary Report 1. Introduction This report provides a summary of the consultation process and the key points/ comments received during the public consultation on the draft Hackbridge Masterplan. Officers comments and considerations are also included. The consultation responses will assist the Council in developing its approach towards future plans for Hackbridge as a sustainable suburb. The draft Hackbridge Masterplan builds on feedback received from public consultation over the last 3 years on how Hackbridge can become a sustainable neighbourhood, including consultation on the ‘Draft Hackbridge Supplementary Planning Document- Towards a Sustainable Suburb: Issues and Options’ in October 2006, a ‘One Planet Living’ Review in April 2007, Developers’ Panel in June 2007, Hackbridge Week in February 2008 and Stakeholder Workshops in September 2008. The preparation of the draft Masterplan following the above consultations has assisted in informing policies put forward for Hackbridge in the Core Planning Strategy and Site Development Policies. The consultation feedback on the draft Masterplan, together with further detailed studies and considerations will eventually feed into the preparation of a Hackbridge Supplementary Planning Document, providing detailed planning guidance on the future development and delivery of the Hackbridge ‘Sustainable Suburb’.