Nesbit Dissertation Dance Curriculum Through Lived

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

60S Hits 150 Hits, 8 CD+G Discs Disc One No. Artist Track 1 Andy Williams Cant Take My Eyes Off You 2 Andy Williams Music To

60s Hits 150 Hits, 8 CD+G Discs Disc One No. Artist Track 1 Andy Williams Cant Take My Eyes Off You 2 Andy Williams Music to watch girls by 3 Animals House Of The Rising Sun 4 Animals We Got To Get Out Of This Place 5 Archies Sugar, sugar 6 Aretha Franklin Respect 7 Aretha Franklin You Make Me Feel Like A Natural Woman 8 Beach Boys Good Vibrations 9 Beach Boys Surfin' Usa 10 Beach Boys Wouldn’T It Be Nice 11 Beatles Get Back 12 Beatles Hey Jude 13 Beatles Michelle 14 Beatles Twist And Shout 15 Beatles Yesterday 16 Ben E King Stand By Me 17 Bob Dylan Like A Rolling Stone 18 Bobby Darin Multiplication Disc Two No. Artist Track 1 Bobby Vee Take good care of my baby 2 Bobby vinton Blue velvet 3 Bobby vinton Mr lonely 4 Boris Pickett Monster Mash 5 Brenda Lee Rocking Around The Christmas Tree 6 Burt Bacharach Ill Never Fall In Love Again 7 Cascades Rhythm Of The Rain 8 Cher Shoop Shoop Song 9 Chitty Chitty Bang Bang Chitty Chitty Bang Bang 10 Chubby Checker lets twist again 11 Chuck Berry No particular place to go 12 Chuck Berry You never can tell 13 Cilla Black Anyone Who Had A Heart 14 Cliff Richard Summer Holiday 15 Cliff Richard and the shadows Bachelor boy 16 Connie Francis Where The Boys Are 17 Contours Do You Love Me 18 Creedance clear revival bad moon rising Disc Three No. Artist Track 1 Crystals Da doo ron ron 2 David Bowie Space Oddity 3 Dean Martin Everybody Loves Somebody 4 Dion and the belmonts The wanderer 5 Dionne Warwick I Say A Little Prayer 6 Dixie Cups Chapel Of Love 7 Dobie Gray The in crowd 8 Drifters Some kind of wonderful 9 Dusty Springfield Son Of A Preacher Man 10 Elvis Presley Cant Help Falling In Love 11 Elvis Presley In The Ghetto 12 Elvis Presley Suspicious Minds 13 Elvis presley Viva las vegas 14 Engelbert Humperdinck Please Release Me 15 Erma Franklin Take a little piece of my heart 16 Etta James At Last 17 Fontella Bass Rescue Me 18 Foundations Build Me Up Buttercup Disc Four No. -

Cariani – 1 Review Article Life's Journey Through the Semiosphere* Peter Cariani As Its Title Suggests, Signs of Meaning In

Cariani – 1 Review article Life’s journey through the semiosphere* Peter Cariani As its title suggests, Signs of Meaning in the Universe by Jesper Hoffmeyer is a wide-ranging survey of the signs and meanings that are embedded in biological organisms. In its roughly 150 pages, Hoffmeyer covers most of the major aspects of the semiosphere that are given to us from biological evolution, proceeding from primitive sign-distinctions through biological codes, neural organizations, and umwelts to self-representation, language, and ethics. The scope of the book is cosmological, with the universal progression from simple to complex evoking echoes of Bergson’s Creative Evolution. In both works the major theme involves the formation of ever more autonomous material organizations that gradually lift matter from inert, time-bound reactivity to ever wider realms of spatio-temporal freedom and epistemic autonomy. Hoffmeyer’s presentation is necessarily dense in concepts, with a new concept making its appearance about every other page. The tone of the book is light-hearted, playful, witty, and disarming, and the illustrative examples that have been chosen are generally appropriate and insightful. While the fast pace and wide- ranging nature of the ideas is refreshing, as the reader is cheerfully shuttled from one semiotic arena to the next, it is difficult to stop to critically evaluate them. This review will attempt to critically reflect on the major ideas, and to consider some alternative formulations. Throughout the book, Hoffmeyer addresses two parallel sets of concerns that involve (in characteristically Danish fashion) questions of existence and questions of biosemiotics. The existential questions involve the meaning of life and the various problems we face in coming to terms with our place in the universe. -

Semiosphere As a Model of Human Cognition

494 Aleksei Semenenko Sign Systems Studies 44(4), 2016, 494–510 Homo polyglottus: Semiosphere as a model of human cognition Aleksei Semenenko Department of Slavic and Baltic Languages Stockholm University 106 91 Stockholm, Sweden e-mail: [email protected] Abstract. Th e semiosphere is arguably the most infl uential concept developed by Juri Lotman, which has been reinterpreted in a variety of ways. Th is paper returns to Lotman’s original “anthropocentric” understanding of semiosphere as a collective intellect/consciousness and revisits the main arguments of Lotman’s discussion of human vs. nonhuman semiosis in order to position it in the modern context of cognitive semiotics and the question of human uniqueness in particular. In contrast to the majority of works that focus on symbolic consciousness and multimodal communication as specifi cally human traits, Lotman accentuates polyglottism and dialogicity as the unique features of human culture. Formulated in this manner, the concept of semiosphere is used as a conceptual framework for the study of human cognition as well as human cognitive evolution. Keywords: semiosphere; cognition; polyglottism; dialogue; multimodality; Juri Lotman Th e concept of semiosphere is arguably the most infl uential concept developed by the semiotician and literary scholar Juri Lotman (1922–1993), a leader of the Tartu- Moscow School of Semiotics and a founder of semiotics of culture. In a way, it was the pinnacle of Lotman’s lifelong study of culture as an intrinsic component of human individual -

Can the Precariat Sing? Standing in Lotman's Light of Cultural Semiotics

Postcolonial Interventions, Vol. V, Issue 2 Can the Precariat Sing? Standing in Lotman’s Light of Cultural Semiotics Ariktam Chatterjee & Arzoo Saha In the most Biblical sense, I am beyond repentance But in the cultural sense, I just speak in future tense (Gaga 2011, n.pg.) In his preface to the Bloomsbury Academic edition of The Rise of the Precariat published in 2016, Guy Standing observes: …more of those in the precariat have come to see themselves, not as failures or shirkers, but as sharing a common predicament with many others. This rec- ognition – a move from feelings of isolation, self-pity or self-loathing, to a sense of collective strength – is 46 Postcolonial Interventions, Vol. V, Issue 2 a precondition of political action…It is organizing, and struggling to define a new forward march. (x) This is a noteworthy evolution in Standing’s formulation from the time this influential study was first published in the form of a book in 2011, and later in 2016, where the precariat was seen to be too diverse and divided to consolidate themselves into a class. It was calibrated re- peatedly as a ‘class-in-the-making’. The group was never a homogenous one. Constituencies were numerous and except for an exploitative and alienated relationship with a neoliberal global economic structure (itself in various degrees of gradation), there was no platform of shared interest. In many ways, it seemed to subvert the notion of shared interest, which was a hallmark of all prior class formation – or what constituted class formation. How- ever, Standing’s present observation betrays a sense that the class has become consolidated. -

Redalyc.Intersemiotic Translation from Rural/Biological to Urban

Razón y Palabra ISSN: 1605-4806 [email protected] Universidad de los Hemisferios Ecuador Sánchez Guevara, Graciela; Cortés Zorrilla, José Intersemiotic Translation from Rural/Biological to Urban/Sociocultural/Artistic; The Case of Maguey and Other Cacti as Public/Urban Decorative Plants.” Razón y Palabra, núm. 86, abril-junio, 2014 Universidad de los Hemisferios Quito, Ecuador Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=199530728032 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative RAZÓN Y PALABRA Primera Revista Electrónica en Iberoamerica Especializada en Comunicación. www.razonypalabra.org.mx Intersemiotic Translation from Rural/Biological to Urban/Sociocultural/Artistic; The Case of Maguey and Other Cacti as Public/Urban Decorative Plants.” Graciela Sánchez Guevara/ José Cortés Zorrilla.1 Abstract. This paper proposes, from a semiotic perspective on cognition and working towards a cognitive perspective on semiosis, an analysis of the inter-semiotic translation processes (Torop, 2002) surrounding the maguey and other cacti, ancestral plants that now decorate public spaces in Mexico City. The analysis involves three semiotics, Peircean semiotics, bio-semiotics, and cultural semiotics, and draws from other disciplines, such as Biology, Anthropology, and Sociology, in order to construct a dialogue on a trans- disciplinary continuum. The maguey and other cactus plants are resources that have a variety of uses in different spaces. In rural spaces, they are used for their fibers (as thread in gunny sacks, floor mats, and such), for their leaves (as roof tiles, as support beams, and in fences), for their spines (as nails and sewing needles), and their juice is drunk fresh (known as aguamiel or neutli), fermented (a ritual beverage known as pulque or octli), or distilled (to produce mescal, tequila, or bacanora). -

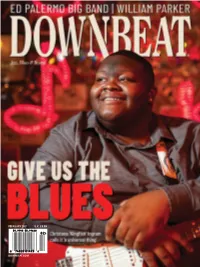

Downbeat.Com February 2021 U.K. £6.99

FEBRUARY 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM FEBRUARY 2021 DOWNBEAT 1 FEBRUARY 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

The Semiosphere, Between Informational Modernity and Ecological Postmodernity Pierre-Louis Patoine and Jonathan Hope

Document generated on 09/29/2021 12:07 a.m. Recherches sémiotiques Semiotic Inquiry The Semiosphere, Between Informational Modernity and Ecological Postmodernity Pierre-Louis Patoine and Jonathan Hope J. M. Lotman Article abstract Volume 35, Number 1, 2015 The notion of semiosphere is certainly one of Lotman’s most discussed ideas. In this essay, we propose to investigate its ecological and biological dimensions, URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1050984ar tracing them back to Vernadsky’s concept of biosphere and to Lotman’s DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1050984ar environmental vision of art articulated in his early work, The Structure of the Artistic Text. Our investigation reveals how the biosemiotic undercurrents in See table of contents Lotmanian thought enable the emergence of a cyclical, homeostatic model of culture that counterbalances a Modernist vision of art as a force working for unquestioned linear progress. Publisher(s) Association canadienne de sémiotique / Canadian Semiotic Association ISSN 0229-8651 (print) 1923-9920 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Patoine, P.-L. & Hope, J. (2015). The Semiosphere, Between Informational Modernity and Ecological Postmodernity. Recherches sémiotiques / Semiotic Inquiry, 35(1), 11–26. https://doi.org/10.7202/1050984ar Tous droits réservés © Association canadienne de sémiotique / Canadian This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit Semiotic Association, 2018 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. -

On the Semiosphere, Revisited

Yorgos Marinakis On the Semiosphere, Revisited Abstract The semiosphere is frequently described as a topos of complexification, namely discontinuous or heterogeneous, recursive or self-reflexive, stochastic, radically subjective, and capable of simultaneous multiple perspectives. While the topos of complexification describes the gross morphology of a model, it is not a model adequate for explaining phenomena or making predictions. The ecological theory of dual hierarchies is proposed as a framework for developing models of the semiosphere that are appropriately limited in scope and scale. In particular the semiosphere is modeled as a dual hierarchy of semiotic spaces, the dual hierarchies corresponding to the semiosis that is occurring within the dual hierarchies of ecological organization. This framework immediately solves several theoretical problems, such as clearing up conceptual inconsistencies in Lotman's concept of semiosphere. Keywords: semiotics, semiosphere, ecosystem, hierarchy theory, category theory, semiotic triad Introduction Juri Lotman's (2005) On the semiosphere, first published in 1984, introduced the concept of the semiosphere and attempted to describe its gross structural features in broad terms. The semiosphere is defined as the semiotic space outside of which semiosis cannot exist, where semiosis is any form of activity, conduct, or process that involves signs. On its face, the structure of Lotman's concept of semiosphere has difficulties, but by focusing on these difficulties one loses sight of the value of the concept. Lotman's conceives of the semiosphere as a space that carries an abstract character and possessing signs, which space he asserts is not metaphorical (therefore not abstract?) but specific (therefore material and not abstract?). -

September-October 2017 September-October Tyle

www.lowrey.com Wood Dale, IL 60191 Wood EZ Play Song Book Special Offers 989 AEC Drive Welcome Back! LIFE Lowrey Since L.I.F.E. has been on summer vacation, we’d like September Carole King to take this time to say hello to everyone with our “Back E-Z Play Today - Vol. 133 to Lowrey” L.I.F.E.Style Edition. Over the summer, 16 smash hits: Beautiful • Chains • Home Lowrey headquarters in Wood Dale Illinois played host to Again • I Feel the Earth Move • It’s Too Late • The Loco-Motion • (You Make Me L.I.F.E. members, students, and dealers in different events tyle Feel Like) A Natural Woman • So Far and functions. Away • Sweet Seasons • Tapestry • Up on Lacefield Music, from St. Charles and St. Louis Mis- the Roof • Where You Lead • Will You souri, visited early this summer with fifty guests! Lacefield 2017 September-October Love Me Tomorrow • You’ve Got a Friend L.I.F.E. members and students began their trip with a S • and more. quick tour of the Lowrey facility, seeing firsthand the ins Regular Price $9.99 and outs of the Lowrey headquarters. Afterwards, they Use L.I.F.E. discount code: LL09 Hal Leonard Book #: 00100306 were treated to a concert by Bil Curry and Jim Wieda, where they received a special showing and musical demon- October Walk The Line stration of the Lowrey Rialto. Lacefield staff and students E-Z Play Today had an enjoyable day in Wood Dale Illinois immersed in Channel: Youtube Check out the Lowrey Vol. -

Eating the Other. a Semiotic Approach to the Translation of the Culinary Code

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI TORINO (UNITO) UNIVERSITÀ DELLA SVIZZERA ITALIANA (USI) Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici (UNITO) / Faculty of Communication Sciences (USI) DOTTORATO DI RICERCA (IN CO-TUTELA) IN: Scienze del Linguaggio e della Comunicazione (UNITO) / Scienze della Comunicazione (USI) CICLO: XXVI (UNITO) TITOLO DELLA TESI: Eating the Other. A Semiotic Approach to the Translation of the Culinary Code TESI PRESENTATA DA: Simona Stano TUTORS: prof. Ugo Volli (UNITO) prof. Andrea Rocci (USI) prof. Marcel Danesi (UofT, Canada e USI, Svizzera) COORDINATORI DEL DOTTORATO: prof. Tullio Telmon (UNITO) prof. Michael Gilbert (USI) ANNI ACCADEMICI: 2011 – 2013 SETTORE SCIENTIFICO-DISCIPLINARE DI AFFERENZA: M-FIL/05 EATING THE OTHER A Semiotic Approach to the Translation of the Culinary Code A dissertation presented by Simona Stano Supervised by Prof. Ugo Volli (UNITO, Italy) Prof. Andrea Rocci (USI, Switzerland) Prof. Marcel Danesi (UofT, Canada and USI, Switzerland) Submitted to the Faculty of Communication Sciences Università della Svizzera Italiana Scuola di Dottorato in Studi Umanistici Università degli Studi di Torino (Co-tutorship of Thesis / Thèse en Co-tutelle) for the degree of Ph.D. in Communication Sciences (USI) Dottorato in Scienze del Linguaggio e della Comunicazione (UNITO) May, 2014 BOARD / MEMBRI DELLA GIURIA: Prof. Ugo Volli (UNITO, Italy) Prof. Andrea Rocci (USI, Switzerland) Prof. Marcel Danesi (UofT, Canada and USI, Switzerland) Prof. Gianfranco Marrone (UNIPA, Italy) PLACES OF THE RESEARCH / LUOGHI IN CUI SI È SVOLTA LA RICERCA: Italy (Turin) Switzerland (Lugano, Geneva, Zurich) Canada (Toronto) DEFENSE / DISCUSSIONE: Turin, May 8, 2014 / Torino, 8 maggio 2014 ABSTRACT [English] Eating the Other. A Semiotic Approach to the Translation of the Culinary Code Eating and food are often compared to language and communication: anthropologically speaking, food is undoubtedly the primary need. -

Prestige Label Discography

Discography of the Prestige Labels Robert S. Weinstock started the New Jazz label in 1949 in New York City. The Prestige label was started shortly afterwards. Originaly the labels were located at 446 West 50th Street, in 1950 the company was moved to 782 Eighth Avenue. Prestige made a couple more moves in New York City but by 1958 it was located at its more familiar address of 203 South Washington Avenue in Bergenfield, New Jersey. Prestige recorded jazz, folk and rhythm and blues. The New Jazz label issued jazz and was used for a few 10 inch album releases in 1954 and then again for as series of 12 inch albums starting in 1958 and continuing until 1964. The artists on New Jazz were interchangeable with those on the Prestige label and after 1964 the New Jazz label name was dropped. Early on, Weinstock used various New York City recording studios including Nola and Beltone, but he soon started using the Rudy van Gelder studio in Hackensack New Jersey almost exclusively. Rudy van Gelder moved his studio to Englewood Cliffs New Jersey in 1959, which was close to the Prestige office in Bergenfield. Producers for the label, in addition to Weinstock, were Chris Albertson, Ozzie Cadena, Esmond Edwards, Ira Gitler, Cal Lampley Bob Porter and Don Schlitten. Rudy van Gelder engineered most of the Prestige recordings of the 1950’s and 60’s. The line-up of jazz artists on Prestige was impressive, including Gene Ammons, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Booker Ervin, Art Farmer, Red Garland, Wardell Gray, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Milt Jackson and the Modern Jazz Quartet, “Brother” Jack McDuff, Jackie McLean, Thelonious Monk, Don Patterson, Sonny Rollins, Shirley Scott, Sonny Stitt and Mal Waldron. -

Whiskey Strings Tour

K k ROCKTOBER 2017 K g VOL. 29 #9 H WOWHALL.ORGk artist, and newly graduated with (Sara Bareilles, Tori Amos) and a Bachelors of Music Composition Benny Cassette (Kanye West) in from Cornish College of the Arts, 2014. Her smash single “Secrets” she had begun to establish herself launched to No. 1 on the Billboard MARY around the Seattle area performing Dance charts, and was certified slam poetry and fusing a talk- RIAA Gold in 2015. The New singing style into her intimate York Times called her debut album performances. She received a “refreshing and severely personal.” LAMBERT phone call from a friend who was All though the success, Mary working with Macklemore and had her inner struggles. Ryan Lewis on their debut album Lambert was raised in an The Heist. Macklemore and Lewis abusive home, attempted suicide IS A were struggling to write a chorus at 17, turned to drugs and alcohol for their new song, a marriage- before being diagnosed with equality anthem called “Same bipolar disorder, and survived Love”. Lambert had three hours multiple sexual assaults throughout BABE to write the hook, and the result her childhood. With that list of was the transcendent and beautiful horrors, you wouldn’t expect Mary chorus to Macklemore & Ryan to be disarmingly joyful, but she (AND SO ARE YOU) Lewis’ triple-platinum hit “Same charms effortlessly, and the effect Love”, which Lambert wrote from on her audience is bewitching. her vantage point of being both a She describes her performances Christian and a lesbian. as, “safe spaces where crying is Writing and singing the hook encouraged.” Mary Lambert says, led to two Grammy nominations “My entire prerogative is about for “Song Of The Year” and connection, about being present, By Maya Vagner Mal Blum.