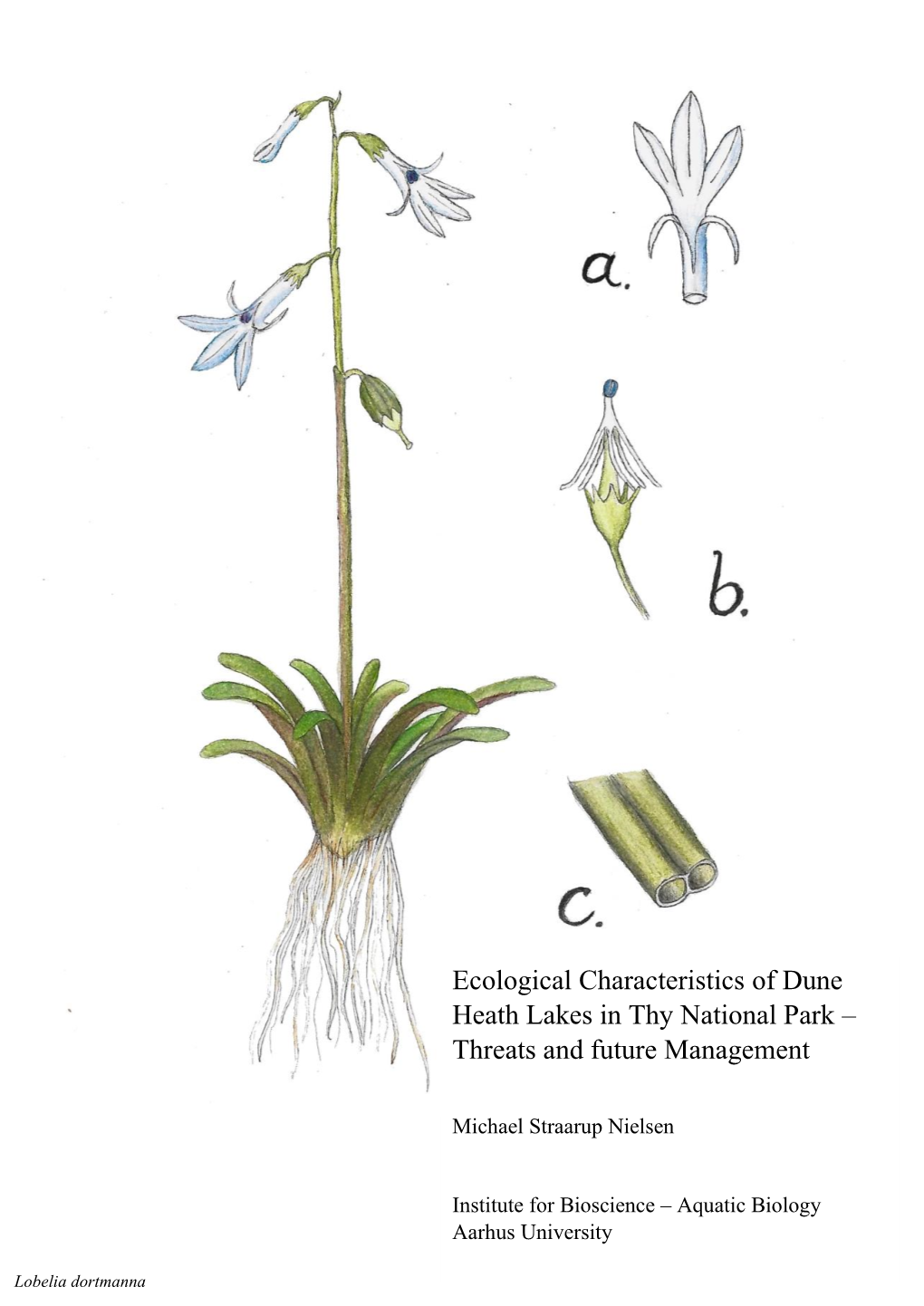

Ecological Characteristics of Dune Heath Lakes in Thy National Park – Threats and Future Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LIVELAND Liveable Landscapes: a Key Value for Sustainable Territorial Development

LIVELAND Liveable Landscapes: a key value for sustainable territorial development Targeted Analysis 2013/2/22 Inception Report | Version 05/July/2012 ESPON 2013 1 This report presents a more detailed overview of the analytical approach to be applied by the project. This Targeted Analysis is conducted within the framework of the ESPON 2013 Programme, partly financed by the European Regional Development Fund. The partnership behind the ESPON Programme consists of the EU Commission and the Member States of the EU27, plus Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. Each partner is represented in the ESPON Monitoring Committee. This report does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the members of the Monitoring Committee. Information on the ESPON Programme and projects can be found on www.espon.eu The web site provides the possibility to download and examine the most recent documents produced by finalised and ongoing ESPON projects. This basic report exists only in an electronic version. © ESPON & TECNALIA, 2012. Printing, reproduction or quotation is authorised provided the source is acknowledged and a copy is forwarded to the ESPON Coordination Unit in Luxembourg. ESPON 2013 i List of authors Lead partner Tecnalia (Spain) Efrén Feliu, Gemma García Regional Partners Alterra (The Netherlands) Rob Schroeder, Bas Pedroli HHP (Germany) Gottfried Hage University of Kassel (Germany) Diedrich Bruns, Boris Stemmer NASUVINSA (Spain) José María Jiménez, Dámaso Munárriz Nordregio (Sweden) Rasmus Ole Rasmussen, Lisbeth Greve Harbo, Ryan Weber REC (Slovenia) Mateja Sepec Jersic, Milena Marega, Blanka Koron ESPON 2013 ii Table of contents 1. LIVELAND general analytical approach ........................................................................ 1 2. Methodology and hypothesis for further investigation.............................................. -

Coastal Living in Denmark

To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. Coastal living in Denmark © Daniel Overbeck - VisitNordsjælland To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. The land of endless beaches In Denmark, we look for a touch of magic in the ordinary, and we know that travel is more than ticking sights off a list. It’s about finding wonder in the things you see and the places you go. One of the wonders that we at VisitDenmark are particularly proud of is our nature. Denmark has wonderful beaches open to everyone, and nowhere in the nation are you ever more than 50km from the coast. s. 2 © Jill Christina Hansen To change the color of the coloured box, right-click here and select Format Background, change the color as shown in the picture on the right. Denmark and its regions Geography Travel distances Aalborg • The smallest of the Scandinavian • Copenhagen to Odense: Bornholm countries Under 2 hours by car • The southernmost of the • Odense to Aarhus: Under 2 Scandinavian countries hours by car • Only has a physical border with • Aarhus to Aalborg: Under 2 Germany hours by car • Denmark’s regions are: North, Mid, Jutland West and South Jutland, Funen, Aarhus Zealand, and North Zealand and Copenhagen Billund Facts Copenhagen • Video Introduction • Denmark’s currency is the Danish Kroner Odense • Tipping is not required Zealand • Most Danes speak fluent English Funen • Denmark is of the happiest countries in the world and Copenhagen is one of the world’s most liveable cities • Denmark is home of ‘Hygge’, New Nordic Cuisine, and LEGO® • Denmark is easily combined with other Nordic countries • Denmark is a safe country • Denmark is perfect for all types of travelers (family, romantic, nature, bicyclist dream, history/Vikings/Royalty) • Denmark has a population of 5.7 million people s. -

CBD Fourth National Report

Fourth Country Report to CBD, Denmark, Januar 2010 CONTENTS Executive summary _______________________________________________________ 4 Chapter I: Overview of Biodiversity Status, Trends and Threats __________________ 7 Introduction __________________________________________________________________________ 7 The agricultural landscape ______________________________________________________________ 8 The agricultural landscape ______________________________________________________________ 8 Key issues ___________________________________________________________________________________ 8 Factors affecting status _________________________________________________________________________ 8 Current status _________________________________________________________________________________ 8 Open habitats ________________________________________________________________________ 13 Key issues __________________________________________________________________________________ 13 Factors affecting status ________________________________________________________________________ 13 Current status ________________________________________________________________________________ 13 Objectives __________________________________________________________________________________ 13 Forests ______________________________________________________________________________ 16 Key issues __________________________________________________________________________________ 16 Factors affecting status ________________________________________________________________________ -

Where Are We Now?

Education Module #29 Week 28 - August 6, 2012 Page 1 Where are we now? Darren and Sandy are in Copenhagen, Denmark, located at 55 N and 12 E. We have traveled approximately 31,912 miles (51,357 kilometers) from our starting point in California. Education Module #29 Week 28 - August 6, 2012 Page 2 People and Culture Denmark ruled most of its neighbors (Sweden, Norway, southern Finland, Iceland, Faroe Islands and Greenland) in the Kalmar Union from 1397 to 1524. The Faroe Islands and Greenland are still within the Kingdom of Denmark. Today the population is about 5.6 million. About 90% of the population is of Danish Copenhagen (source: Flickr.com/JamesZ_Flickr) descent. Copenhagen is the capital city. The Stroget is Did you know? one of the longest shopping streets in Europe. William Shakespeare’s fictional Hamlet was a Tivoli Gardens in Copenhagen is the second- Danish prince. The play’s setting is in a castle in oldest amusement park in the world. It Helsingør, or Elsinore, Denmark. opened in 1843. It is said to have inspired The castle located Walt Disney’s creation of Disneyland. there is called Kronborg Castle. Hans Christian Anderson is a famous fairy tale It was first built in 1420 and is now a author. His tales include “The Emperor’s New World Heritage site. Clothes”, “The Little Mermaid” and “The Ugly Duckling”. A Little Mermaid statue is located in source: Copenhagen. Copenhagenet.dk One well-known Danish invention is the Lego. They were produced beginning in 1932. source: Flickr.com/Taylor McConnell Education Module #29 Week 28 - August 6, 2012 Page 3 Nature and Environment Denmark is located on a peninsula, called Jutland, and a Greenland series of islands. -

The Rise of Canis Lupus in Europe

WolfThe UK Wolf Conservation Trust PrintIssue 52 Summer 2014 The rise of canis lupus in Europe Wolves return to Denmark after two centuries of absence The Iberian wolf African adventure How the work of Grupo Lobo is An unforgettable wolf encounter helping this small, distinct species in Ethiopia ■ NEWS ■ EVENTS ■ RESEARCH ■ MEDIA AND ARTS ISSUE 52 SUMMER 2014 | 1 WOLF PRINT Issue 52 Tala and Julia by Veda Kavanagh Editor’s Editor Julia Bohanna Letter Tel: 0118 971 3330 Email: [email protected] Editorial Team Wendy Brooker n May this year, Europe Nikki Davies Pete Haswell was very much a major Cammie Kavanagh Idiscussion point in the field Lynn Kent of human politics. It will of Pete Morgan-Lucas course be on our agenda Tsa Palmer Denise Taylor one way or the other for the foreseeable future. Wolves may not read, vote or elect politicians, but they have made huge inroads into parts of Patrons Martin ‘Wolfie’ Adams Europe, particularly in places where they have not be seen for many years. David Clement-Davies Our piece on wolves now populating Denmark (pages 18–19) in particular Cornelia ‘Neil’ Hutt shows an exciting development; we will follow this news at Wolf Print with Desmond Morris Marco Musiani great interest. Technology and human patience – recording lupine noises Michelle Paver – eventually solved a mystery and gave confirmation of a new wolf family The UK Wolf Conservation Trust Directors in Denmark. The feature on wolves (and other wildlife) thriving in the Nigel Bulmer troubled and tragic Chernobyl continues the theme of animal resilence Charles Hicks and determination. -

Hanstholm Nature Reserve and Tved Dune Plantation Holm I” Battery Near Kystvejen Just North of the Reserve Is Well-Preserved

Welcome to Hanstholm Nature Reserve Hanstholm and Tved Dune Plantation Tved Dune Plantation and Hanstholm Nature Reserve constitute the most Nature Reserve northerly section of the Thy national park. The area is a wonderful illu- stration of all the types of landscape and habitat specific to the national park. and Tved Dune Practical information You are welcome to ride your horse on the gravel paths, using the verge or outer shoulder. Please note that riding is not permitted in Hanstholm Nature Reserve. Plantation The many forest tracks are perfect for cycling. The newly laid cycle track along Kystvejen means that you can now cycle round the perimeter of the reserve, a tour of approximately 40 km. Tved Church was once surrounded by fields. Sand drift forced farmers to move eastwards. Drawing by J. Magnus-Pedersen, 1875 Peter Odgaards Plads at Sårup is a simple camping area with shelters, bonfire site, privy, water and firewood. The camping area is for the use of walkers and cyclists. A reservation in Tved Church advance is necessary if you are planning a trip as a larger group. Tved church is a Romanesque structure believed to date from the 1100s. The There is a bonfire site and barbecue area between Bagsø and church was once surrounded by a small town, but drifting sands resulted in Nors Lake. Firewood is freely available. the departure of inhabitants of the parish, so that all its houses now lie east of the country road. The interior walls are decorated with chalk paintings dating Fishing is allowed at Bagsø. Those with mobility impairments from 1100-1500, the largest of which depicts the Garden of Eden transposed may use the fishing platform. -

Eels in Culture, Fisheries and Science in Denmark 3

Eels in Culture, Fisheries and Science in Denmark 3 Suzanne Rindom , Jonna Tomkiewicz , Peter Munk , Kim Aarestrup , Thomas Damm Als , Michael Ingemann Pedersen , Christian Graver , and Carina Anderberg As in many other parts of the world, eels and their mysterious migration and captive reproduction of eels is widely life cycle have always fascinated Danes. Almost everyone in respected. Denmark, no matter their age, knows something about eels. Many aspects of eel biology still remain a mystery, how- In fact, the eel was once one of the country’s most important ever, so Danish research on European eels continues in a food fi sh, and Denmark itself was one of the main European national as well as an international context. Some of the nations fi shing it, partly because of the seasonal abundance history and current knowledge is outlined briefl y here, and we of migrating silver eels leaving the Baltic Sea through the also discuss the long-standing relationship between humans narrow Straits of Denmark. Eels were fi shed year-round even and eels in Denmark, including looking at the signifi cance of during winter (Fig. 3.1 ). Although the Danish eel fi shery was eels in Danish culture and society, e.g. in fi sheries and as food. carried out mainly by smallholders, eels were for many years traded extensively with other European countries. Today, though, fi sheries for eels are limited by low abundance and consequently restrictive laws. Eel Biology Denmark has a long tradition of research into the biology and ecology of the European eel (Anguilla anguilla ). -

Stenbjerg in Thy Stenbjerg Dune Plantation from the Car Park on Stenbjergvej Stenbjerg the Løvbakke Trail Red, 1.2 Km

Marked nature trails Welcome to Stenbjerg in Thy Stenbjerg dune plantation from the car park on Stenbjergvej Stenbjerg The Løvbakke trail red, 1.2 km. Follows mixed terrain with a variety of tree species. Roughly at the centre of Thy’s national park lies the attractive Stenbjerg The Embak trail yellow, 5.7 km. Starts in undulating, varied forest and takes landing place, a group of fishermen’s huts by the sea against a backdrop of in Thy in the Bislet wetlands and Embak Vand. dunes, heath, and forestry plantations. The varied natural landscape of this area offers many opportunities for outdoor activities. Stenbjerg dune plantation from the car park at Førby Linie The Enebærsø trail blue, 2.3 km. Traverses a section of burned plantation Nature trails: This leaflet describes nine marked trails and suggests and skirts the Enebær lakes. three unmarked routes. Cycling trails: The West Coast Route (national cycle trail no. 1) runs Stenbjerg dune plantation from the car park on Kystvej through the area, and cycling is also permitted on the many good forest The Bislet trail red, 1.5 km. Heads for the viewing tower and follows the roads. southern edge of Bislet. The Fredskilde trail green, 8 km. Is a continuation to the east of the red trail. The West Coast Route /North Sea Trail: The section of the North Sea The depression leads to more fertile woodland south of Fredskilde lake. Trail that runs through Thy coincides with the West Coast Route Agger- Bulbjerg and to a large extent follows the old Rescue Route northwards. -

The Best of Denmark's Nature 88

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 08/24/2021 1:59:27 PM Anna Nielsen From: VisitDenmark <[email protected]> Sent: 26. februar 2021 07:59 To: Anna Nielsen Subject: Are you counting the days until spring? We are! VisitDenmark The best of Denmark's nature am 88 i: * > * I rA .1 Hornbaek Plantage © Daniel Overbeck, VisitNordsjaelland Now that winter's on the way out, we're dusting off our hiking boots and unfolding maps, dreaming of ways to embrace friluftsliv (our love of being outside in the free air). With five unique national parks to explore, Denmark has space and fresh air by the bucketload. Not to mention beaches, forests, easy hiking routes, hills, traces of the Vikings, fjords and ooh, lots more... Take an armchair trip with us Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 08/24/2021 1:59:27 PM Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 08/24/2021 1:59:27 PM K.*< . yfe. j ..u ■. '..j, •-• y. m. *■ ■f 3 r' m . ■■! * ~ ~~ The King's Garden © Astrid Maria Rasmussen, Copenhagen Central Hotel & Cafe © Andrea Nunez, Copenhagen Media Media Center Center Spring in Denmark New hotel trend fa The buds are bursting, the lambs are This story is for those of you who don't jumping and we're all frisky at the like sharing and have had enough of thought of being outside in the pale noisy neighbours. Our new hotel trend spring sunshine again. Take a peek at is the one-room hotel - with no other what spring looks like in Denmark. guests but you. -

Aalborg Universitet the Tales of Limfjorden a Danish Case Of

Aalborg Universitet The Tales of Limfjorden A Danish case of storytelling and destination development Larsen, Jacob Roesgaard Kirkegaard; Therkelsen, Anette Publication date: 2009 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Larsen, J. R. K., & Therkelsen, A. (2009). The Tales of Limfjorden: A Danish case of storytelling and destination development. Tourism Research Unit, Aalborg Universitet. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. ? Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. ? You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ? You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from vbn.aau.dk on: October 02, 2021 TRUprogress © Working papers from the Tourism Research Unit, Aalborg University Working Paper no. 6/December 2009 The Tales of Limfjorden A Danish case of storytelling and destination development by Jacob R. Kierkegaard Larsen & Anette Therkelsen Formål: Ophavsret : Kontak tadresse : TRUprogress © er en serie med længere TRUprogress © er en del af TRUs åbne Tourism Research Unit artikler, hvor det er hensigten, at forskningskoncept. -

Mobility Challenges in the Region of Northern Jutland, Denmark

Aalborg Universitet Mobility Challenges in the Region of Northern Jutland, Denmark Vestergaard, Maria Quvang Lund; Laursen, Lea Louise Holst; Jensen, Ole B.; Lassen, Claus Publication date: 2011 Document Version Early version, also known as pre-print Link to publication from Aalborg University Citation for published version (APA): Vestergaard, M. Q. L., Laursen, L. L. H., Jensen, O. B., & Lassen, C. (2011). Mobility Challenges in the Region of Northern Jutland, Denmark. Paper presented at XXIV European Congress for Rural Sociology, Chania, Crete, Greece. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. ? Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. ? You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain ? You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us at [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from vbn.aau.dk on: September 28, 2021 MOBILITY CHALLENGES IN THE REGION OF NORTHERN JUTLAND, DENMARK Paper for the ESRS 2011, "XXIV European Congress for Rural Sociology", 22-25 August 2011, Chania, Crete, Greece Maria Quvang Lund Vestergaard – Dept. of Development and Planning – [email protected] Lea Louise Holst Laursen - Dept. -

Ulv I Danmark - Konflikter Og Muligheder for Turismeforvaltningen

Forord Denne rapport præsenterer et 10. semesters masterprojekt udarbejdet af Zita Bak-Jensen på Norsk Miljø- og Biovidenskabelige Universitet. Rapporten er udarbejdet i perioden d. 14. december 2015 til d. 13. maj 2016. I rapporten anvendes NMBUs Harvardmetode gennem EndNote til kildeangivelse. Figurer og billeder uden kilder er udarbejdet til projektet af forfatteren selv. I forbindelse med udformningen af projektet, er der modtaget hjælp fra flere kanter, som ønskes takket. Der for vil jeg gerne takke administrationen hos Nationalpark Thy for, at være behjælpelige med deling af spørgeskema og data. Desuden vil jeg gerne takke Nystrup Camping Klitmøller for også at dele undersøgelsen. Der sak også lyde en tak til Eva Janik for oversættelse af spørgeskema. Projektet er skrevet, som et afsluttende projekt til mastergraden i Naturbaseret rejseliv, og vil derfor være henvendt til folk, med en rimelig forståelse for natur og/eller turismeforvaltning. II III Sammendrag Bak-Jensen, Z. Ulv i Danmark - konflikter og muligheder for turismeforvaltningen. Resultater af et litteraturstudie og en eksperimenterende kvantitativ spørgeundersøgelse, Masterprojekt i Naturbaseret Reiseliv ved NMBU 2016, 75 sider I 2012 fandt man for første gang i over 200 år beviser på, at ulven igen var på vej tilbage til de danske landskaber. Beviserne bestod af kadaveret af en ulv, som blev fundet i Hanstholm klitplantage, der er en del af Nationalpark Thy. Ulven er kendt for at være med til at skabe sociale konflikter, hvilket også ses i dagens Danmark. For Nationalpark Thy kan ulvens tilbagevenden være både positiv og negativ set i forhold til besøgsantallet. Gæster kan enten vælge Thy over andre nationalparker, da man her har muligheden for at se et af Danmarks mest omdiskuterede dyr, mens andre fravælger at besøge parken fx pga.