Yemen Multi-Sector Early Recovery Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tor Yemen Nutrition Cluster Revi

Yemen Nutrition Cluster كتله التغذية اليمن https://www.humanitarianresponse.info https://www.humanitarianresponse.info /en/operations/yemen/nutrition /en/operations/yemen/nutrition XXXXXXXX XXXXXXXX YEMEN NUTRITION CLUSTER TERMS OF REFERENCE Updated 23 April 2018 1. Background Information: The ‘Cluster Approach1’ was adopted by the interagency standing committee as a key strategy to establish coordination and cooperation among humanitarian actors to achieve more coherent and effective humanitarian response. At the country level, the aim is to establish clear leadership and accountability for international response in each sector and to provide a framework for effective partnership and to facilitat strong linkages among international organization, national authorities, national civil society and other stakeholders. The cluster is meant to strengthen rather than to replace the existing coordination structure. In September 2005, IASC Principals agreed to designate global Cluster Lead Agencies (CLA) in critical programme and operational areas. UNICEF was designated as the Global Nutrition Cluster Lead Agency (CLA). The nutrition cluster approach was adopted and initiated in Yemen in August 2009, immediately after the break-out of the sixth war between government forces and the Houthis in Sa’ada governorate in northern Yemen. Since then Yemen has continued to face complex emergencies that are largely conflict-generated and in part aggravated by civil unrest and political instability. These complex emergencies have come on the top of an already fragile situation with widespread poverty, food insecurity and underdeveloped infrastructure. Since mid-March 2015, conflict has spread to 20 of Yemen’s 22 governorates, prompting a large-scale protection crisis and aggravating an already dire humanitarian crisis brought on by years of poverty, poor governance and ongoing instability. -

Mocha: Maritime Architecture on Yemen's Red Sea Coast

Binghamton University The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB) Art History Faculty Scholarship Art History 2017 “Mocha: Maritime Architecture on Yemen’s Red Sea Coast.” In ‘Architecture That Fills My Eye’: The Building Heritage of Yemen. Exh. Cat. Ed. Trevor H.J. Marchand, 60-69. London: Gingko Library, 2017. Nancy Um Binghamton University--SUNY, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://orb.binghamton.edu/art_hist_fac Part of the Architectural History and Criticism Commons, Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Nancy Um, “Mocha: Maritime Architecture on Yemen’s Red Sea Coast.” In ‘Architecture That Fills My Eye’: The Building Heritage of Yemen. Exh. Cat. Ed. Trevor H.J. Marchand, 60-69. London: Gingko Library, 2017. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Art History Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. GINGKO LIBRARY ART SERIES Senior Editor: Melanie Gibson Architectural Heritage of Yemen Buildings that Fill my Eye Edited by Trevor H.J. Marchand First published in 2017 by Gingko Library 70 Cadogan Place, London SW1X 9AH Copyright © 2017 selection and editorial material, Trevor H. J. Marchand; individual chapters, the contributors. The rights of Trevor H. J. Marchand to be identified as the author of the editorial material, and of the individual authors as authors of their contributions, has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

Aden Sub- Office May 2020

FACT SHEET Aden Sub- Office May 2020 Yemen remains the world’s Renewed fighting in parts of UNHCR and partners worst humanitarian crisis, with the country, torrential rains provide protection and more than 14 million people and deadly flash floods and assistance to displaced requiring urgent protection and now a pandemic come to families, refugees, asylum- assistance to access food, water, exacerbate the already dire seekers and their host shelter and health. situation of millions of people. communities. KEY INDICATORS 1,082,430 Number of internally displaced persons in the south DTM March 2019 752,670 Number of returnees in the south DTM March 2019 161,000 UNHCR’s partner staff educate a Yemeni man on COVID-19 and key Number of refugees and asylum seekers in the preventive measures during a door-to-door distribution of hygiene material south UNHCR April 2020 including soap, detergent in Basateen, in Aden © UNHCR/Mraie-Joelle Jean-Charles, April 2020. UNHCR PRESENCE Staff: 85 National Staff 14 International Staff Offices: 1 Sub Office in Aden 1 Field Office in Kharaz 2 Field Units in Al Mukalla and Turbah www.unhcr.org 1 FACT SHEET > Aden Sub- Office/ May 2020 Main activities Protection INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS Protection Cluster ■ The Protection Cluster led by UNHCR and co-led by Intersos coordinates the delivery of specialised assistance to people with specific protection needs, including victims of violence and support to community centres, programmes, and protection networks. ■ At the Sub-National level, the Protection Cluster includes more than 40 partners. ■ UNHCR seeks to widen the protection space through protection monitoring (at community and household levels) and provision of protection services including legal, psychosocial support, child protection and prevention and response to sexual and gender-based violence. -

On Conservation and Development: the Role of Traditional Mud Brick Firms in Southern Yemen*

On Conservation and Development: The Role of Traditional Mud Brick Firms in Southern Yemen* Deepa Mehta Graduate School of Architecture, Planning & Preservation** Columbia University in the City of New York New York, NY 10027, USA [email protected] ABSTRACT A study of small and medium enterprises that make up the highly specialized mud brick construction industry in southern Yemen reveals how the practice has been sustained through closely-linked regional production chains and strong firm inter-relationships. Yemen, as it struggles to grow as a nation, has the potential to gain from examining the contribution that these institutions make to an ancient building practice that still continues to provide jobs and train new skilled workers. The impact of these firms can be bolstered through formal recognition and capacity development. UNESCO, ICOMOS, and other conservation agencies active in the region provide a model that emphasizes architectural conservation as well as the concurrent development of the existing socioeconomic linkages. The primary challenge is that mud brick construction is considered obsolete, but evidence shows that the underlying institutions are resilient and sustainable, and can potentially provide positive regional policy implications. Key Words: conservation, planning, development, informal sector, capacity building, Yemen, mud brick construction. * Paper prepared for GLOBELICS 2009: Inclusive Growth, Innovation and Technological Change: education, social capital and sustainable development, October 6th – -

The Special-Purpose Carrier of Pipe Joints

15JULY1988 MEED 25 Ramazarnanpour Ramazanianpour held talks Denktash. says he is ready for financial aspects of its offer. The group — with the ccfnmerce, heavy and light industry unconditional talks with Greek Cypnot Impreqilo, Cogefar and Gruppo m ministers arid visited the Iranian pavilion at the President George Vassiliou about the Industrie Elettromeccaniche per 24th Algiers international fair. future of the divided island. Impiantl all'Estero (GIE)—plans to start • The Mauntanian towns ot Ak|ou|t and Zouerat In March. Denktash insisted any talks work on the diversionary canal for the dam have received equipment including trucks, must be based on a proposal put forward m September (MEED 24:6:88). trailers, water tanks and tractors from their by UNSecretary-General Javier Perez de Bids for construction of the dam, which Algerian twin towns of Staoueli and Ouenza. Cuellar. The proposal has been reacted will replace the old Esna barrage, were by Greek Cypnots. submitted by 12 international groups in Denktash issued his statement on 6 July December 1986. The field was eventually after a three-day visit to Ankara, where he narrowed to three bidders — the Italian BAHRAIN met Turkey's President Evren and Prime group, Yugoslavia's Energoprojekt, and a Minister TurgutOzal. Canadian consortium of The SWC Group • Bahrain National Gas Company (Banagaa) Vassiliou has refused previous offers to and Canadian International produced 3.2 million barrels a day (b/d) ot Construction Corporation. liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) in 1987. This was meet Denktash on the grounds that the highest daily average since 1979 — its first unacceptable preconditions have been The Italian group brought in Switzerland's year of operations — and 5 percent up on the attached to any meeting. -

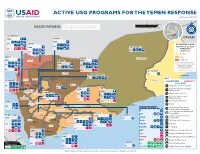

USG Yemen Complex Emergency Program

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE YEMEN RESPONSE Last Updated 02/12/20 0 50 100 mi INFORMA Partner activities are contingent upon access to IC TI PH O A N R U G SAUDI ARABIA conict-aected areas and security concerns. 0 50 100 150 km N O I T E G U S A A D ID F /DCHA/O AL HUDAYDAH IOM AMRAN OMAN IOM IPs SA’DAH ESTIMATED FOOD IPs SECURITY LEVELS IOM HADRAMAWT IPs THROUGH IPs MAY 2020 IPs Stressed HAJJAH Crisis SANA’A Hadramawt IOM Sa'dah AL JAWF IOM Emergency An “!” indicates that the phase IOM classification would likely be worse IPs Sa'dah IPs without current or planned IPs humanitarian assistance. IPs Source: FEWS NET Yemen IPs AL MAHRAH Outlook, 02/20 - 05/20 Al Jawf IP AMANAT AL ASIMAH Al Ghaedha IPs KEY Hajjah Amran Al Hazem AL MAHWIT Al Mahrah USAID/OFDA USAID/FFP State/PRM Marib IPs Hajjah Amran MARIB Agriculture and Food Security SHABWAH IPs IBB Camp Coordination and Camp Al Mahwit IOM IPs Sana'a Management Al Mahwit IOM DHAMAR Sana'a IPs Cash Transfers for Food Al IPs IPs Economic Recovery and Market Systems Hudaydah IPs IPs Food Voucher Program RAYMAH IPs Dhamar Health Raymah Al Mukalla IPs Shabwah Ataq Dhamar COUNTRYWIDE Humanitarian Coordination Al Bayda’ and Information Management IP Local, Regional, and International Ibb AD DALI’ Procurement TA’IZZ Al Bayda’ IOM Ibb ABYAN IOM Al BAYDA’ Logistics Support and Relief Ad Dali' OCHA Commodities IOM IOM IP Ta’izz Ad Dali’ Abyan IPs WHO Multipurpose Cash Assistance Ta’izz IPs IPs UNHAS Nutrition Lahij IPs LAHIJ Zinjubar UNICEF Protection IPs IPs WFP Ready-to-Use Therapeutic Food IOM Al-Houta ADEN FAO Refugee and Migrant Assistance IPs Aden IOM UNICEF Risk Management Policy and Practice Shelter and Settlements IPs WFP SOCOTRA DJIBOUTI, ETHIOPIA, U.S. -

Economic Update

Economic Update NBK Economic Research Department I 3 November 2020 Projects > Ensaf Al-Matrouk Research Assistant +965 2259 5366 Kuwait: Project awards pick up in 3Q as [email protected] > Omar Al-Nakib lockdown measures ease Senior Economist +965 2259 5360 [email protected] Highlights The value of project awards increased almost 82% q/q to KD 192 million in 3Q20. Projects awarded were transport and power/water-related; no oil/gas or construction projects were signed. KD 2.1bn worth of awards were penciled in for 2020, however, we expect a smaller figure to materialize. Project awards gather pace in 3Q20, but still fall short of However, with the economy experiencing only a partial recovery expectations so far the projects market is likely to remain subdued; only projects essential to the development plan are likely to be After reaching a multi-year low of KD 106 million in 2Q20, a prioritized. (Chart 3.) quarter that saw business activity heavily impacted by the coronavirus pandemic, the value of project awards increased . Chart 2: Annual project awards nearly 82% q/q in 3Q20 to reach KD 192 million. This is still KD billion, *includes awarded and planned modest by previous standards, however, and is 45% lower than 9 9 the KD 350 million worth of projects approved in in 3Q19. (Chart 8 Transport 8 Power & Water 1). One project award from the Ministry of Public Works’ (MPW), 7 7 accounted for the bulk (86%) of total project awards in the Oil & Gas 6 Construction 6 quarter. 5 Industrial 5 Total projects awarded in 2020 so far stand at KD 866 million 4 4 (cumulative), with about KD 1.3 billion still planned for 4Q20. -

A New Model for Defeating Al Qaeda in Yemen

A New Model for Defeating al Qaeda in Yemen Katherine Zimmerman September 2015 A New Model for Defeating al Qaeda in Yemen KATHERINE ZIMMERMAN SEPTEMBER 2015 A REPORT BY AEI’S CRITICAL THREATS PROJECT TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Part I: Al Qaeda and the Situation in Yemen ................................................................................................. 5 A Broken Model in Yemen ...................................................................................................................... 5 The Collapse of America’s Counterterrorism Partnership ........................................................................ 6 The Military Situation in Yemen ........................................................................................................... 10 Yemen, Iran, and Regional Dynamics ................................................................................................... 15 The Expansion of AQAP and the Emergence of ISIS in Yemen ............................................................ 18 Part II: A New Strategy for Yemen ............................................................................................................. 29 Defeating the Enemy in Yemen ............................................................................................................ -

42 MEED Listfinal.Indd

“Dubai hopes the [$8bn] The MEED List Q capital injection will allow Nakheel to resume work” Agenda page 20 GCC BOND MARKET LAWYERS Six leading bond market lawyers in the region Craig Stoehr Richard O’Callaghan Anzal Mohammed POSITION Counsel, Latham & Watkins POSITION Partner, Linklaters POSITION Partner, Allen & Overy BIOGRAPHY Craig Stoehr led the opening of BIOGRAPHY Richard O’Callaghn joined Linklaters BIOGRAPHY In 2009, Anzal Mohammed advised Latham & Watkins office in Doha, Qatar in in Dubai in 2008, and worked on high-profile on the world’s largest sovereign sukuk, the 2008. Within 12 months he had worked on transactions in the region, including Abu Dubai government’s $2bn issue. He has a probably more bond deals by value than any- Dhabi’s Tourism Development & Investment strong track-record of working on bond and one else in the market, completing the state of Company’s $1bn sukuk issue in 2009, and its sukuk deals with the Abu Dhabi and Ras al- Qatar’s $7bn bond issue in November 2009, $1bn bond deal in the same year. He recently Khaimah governments, and state-backed cor- and its earlier $3bn deal. Stoehr also worked acted for the lead arrangers on Saudi real estate porates such as Mubadala Development on a $2.3bn bond for Ras Laffan Liquefied Nat- firm Dar al-Arkan’s $450m sukuk issue and is Company, Dubai Electricity & Water Author- ural Gas Company in 2009. His other clients currently representing the lead arrangers on ity, Jebel Ali Free Zone Authority, and the include Qatar Investment Authority, and state- Bahrain’s sovereign bond. -

Thought Leadership Report GCC LOGISTICS 2017

Thought Leadership Report GCC LOGISTICS 2017 Sponsored By: FOREWORD Mark Geilenkirchen, Chief Executive Officer SOHAR Port and Freezone The office we sit in, the clothes we wear and the food we eat all rely on business planning frameworks that manage material, service, information and capital flows around the globe. This is logistics and by necessity, in today’s increasingly complex business environment, it centres on the communication and control systems required to keep our world moving twenty-four hours a day, each and every day of the year. As one of the world’s fastest growing Port and Freezone developments, logistics is at the core of our business in SOHAR and connects us with markets all over the world. As this is our Year of Logistics, we asked MEED Insight to prepare this special report on the Middle East logistics industry as part of a series of SOHAR sponsored thought leadership reports. We define thought leaders as people or organisations whose efforts are aligned to improve the world by sharing their expertise, knowledge, and lessons learned with others. We believe this knowhow can be the spark behind innovative change, and that’s what we’ve set out to inspire by commissioning this series of reports. 2 GCC LOGISTICS 2016 The GCC Economy GCC Macroeconomic Overview GDP GROWTH GCC VISION PLANS The petrodollar fuelled GCC economies been fairly successful in lowering its oil All the GCC states have formalised strategic, have had a strong run during the first dependency to 42% of GDP in 2014, long- term plans aimed at transforming decade of this millennium, registering a down from 55% in 2008. -

0 Desk Study

DESK STUDY Multidimensional Livelihoods Assessment in Conflict-Affected Areas 0 Contents Executive summary ............................................................................................................... 3 I. Introduction ................................................................................................................... 7 1. Background ....................................................................................................................................... 7 2. Objectives.......................................................................................................................................... 8 3. Methodology ..................................................................................................................................... 8 II. Population .................................................................................................................. 8 III. Poverty ....................................................................................................................... 9 IV. Structure of the Yemen economy .............................................................................. 11 V. Impact of the 2011 crisis on employment, skilled and unskilled labour, and the private sector ........................................................................................................................ 12 VI. Main livelihood activities and the impact of conflict on selected sectors .................... 14 A. Main livelihood activities ............................................................................................................... -

The Dubai Logistics Cluster

THE DUBAI LOGISTICS CLUSTER Alanood Bin Kalli, Camila Fernandez Nova, Hanieh Mohammadi, Yasmin Sanie-Hay, Yaarub Al Yaarubi MICROECONOMICS OF COMPETITENESS COUNTRY OVERVIEW The United Arab Emirates (UAE) is a federation of seven emirates, each governed by its own monarch. The seven Emirates - Abu Dhabi, Ajman, Dubai, Fujairah, Ras al-Khaimah, Sharjah, and Umm al-Quwain - jointly form the Federal Supreme Council, which chooses a president every five years. Since independence from Britain in 1971, the ruler of Abu Dhabi has been elected as the president, while the ruler of Dubai has been elected as the Vice President and Prime Minister. Abu Dhabi serves as the capital and each emirate enjoys a high degree of autonomy. The country is strategically located in the Middle East, bordering the Persian Gulf, the Arabian Sea, Oman and Saudi Arabia. It occupies a total area of 83,600 km2 with around 1,318 km of coastline1. The population is estimated to be 9.3 million in 2015 with only 13% nationals2. UAE Economic Performance The UAE is an oil rich country, with most of its oil and gas production coming from Abu Dhabi. The country was ranked eighth worldwide in terms of oil and gas production in 2012 and seventh in terms of reserves3. Since the UAE’s establishment, oil revenues have been used strategically to develop basic infrastructure and provide UAE citizens with government services including subsidized utilities, free education, and medical services. As a result of oil price fluctuation, the country has understood the importance of diversifying away from this resource and started to develop its petrochemical sector.