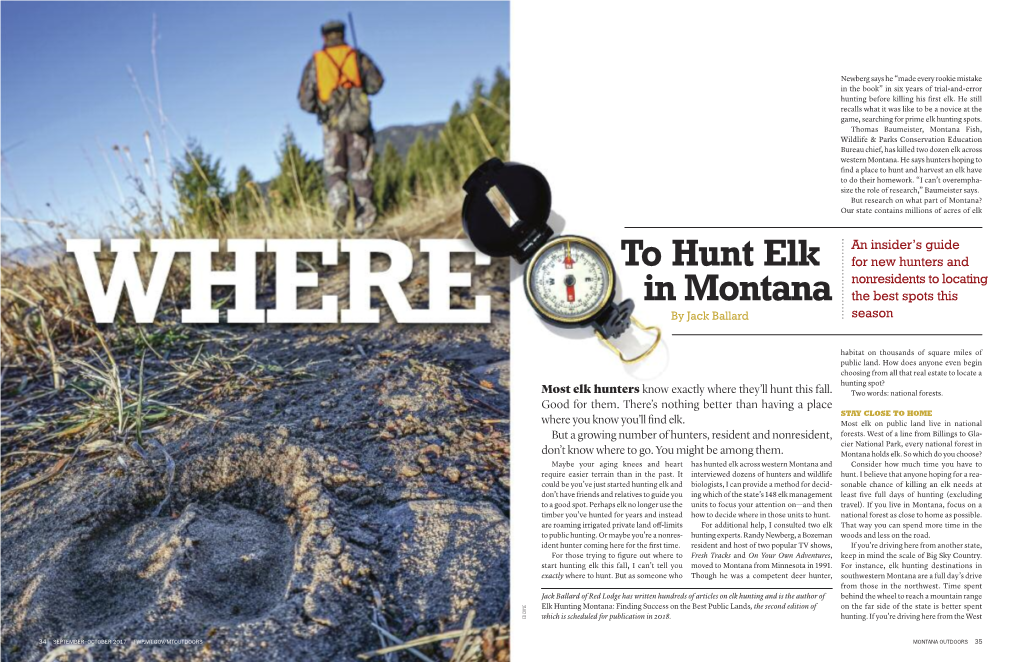

To Hunt Elk in Montana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cervid TB DPP Testing August 2017

Cervid TB DPP Testing August 2017 Elisabeth Patton, DVM, PhD, Diplomate ACVIM Veterinary Program Manager Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade and Consumer Protection Division of Animal Health Why Use the Serologic Test? Employ newer, accurate diagnostic test technology Minimizes capture and handling events for animal safety Expected to promote additional cervid TB testing • Requested by USAHA and cervid industry Comparable sensitivity and specificity to skin tests 2 Historical Timeline 3 Stat-Pak licensed for elk and red deer, 2009 White-tailed and fallow deer, 2010-11 2010 - USAHA resolution - USDA evaluate Stat-Pak as official TB test 2011 – Project to evaluate TB serologic tests in cervids (Cervid Serology Project); USAHA resolution to approve Oct 2012 – USDA licenses the Dual-Path Platform (DPP) secondary test for elk, red deer, white-tailed deer, and fallow deer Improved specificity compared to Stat-Pak Oct 2012 – USDA approves the Stat-Pak (primary) and DPP (secondary) as official bovine TB tests in elk, red deer, white- tailed deer, fallow deer and reindeer Recent Actions Stat-Pak is no longer in production 9 CFR 77.20 has been amended to approve the DPP as official TB program test. An interim rule was published on 9 January 2013 USDA APHIS created a Guidance Document (6701.2) to provide instructions for using the tests https://www.aphis.usda.gov/animal_health/animal_ diseases/tuberculosis/downloads/vs_guidance_670 1.2_dpp_testing.pdf 4 Cervid Serology Project Objective 5 Evaluate TB detection tests for official bovine tuberculosis (TB) program use in captive and free- ranging cervids North American elk (Cervus canadensis) White-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) Primary/screening test AND Secondary Test: Dual Path Platform (DPP) Rapid immunochromatographic lateral-flow serology test Detect antibodies to M. -

Bison and Elk in Yellowstone National Park - Linking Ecosystem, Animal Nutrition, and Population Processes

Bison and Elk in Yellowstone National Park - Linking Ecosystem, Animal Nutrition, and Population Processes Part 3 - Final Report to U.S. Geological Survey Biological Resources Division Bozeman, MT Project: Spatial-Dynamic Modeling of Bison Carrying Capacity in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem: A Synthesis of Bison Movements, Population Dynamics, and Interactions with Vegetation Michael B. Coughenour Natural Resource Ecology Laboratory Colorado State University Fort Collins, Colorado December 2005 INTRODUCTION Over the last three decades bison in Yellowstone National Park have increased in numbers and expanded their ranges inside the park up to and beyond the park boundaries (Meagher 1989a,b, Taper et al. 2000, Meagher et al. 2003). Potentially, they have reached, if not exceeded the capacity of the park to support them. The bison are infected with brucellosis, and it is feared that the disease will be readily transmitted to domestic cattle, with widespread economic repercussions. Brucellosis is an extremely damaging disease for livestock, causing abortions and impaired calf growth. After a long campaign beginning in 1934 and costing over $1.3 billion (Thorne et al. 1991), brucellosis has been virtually eliminated from cattle and bison everywhere in the conterminous United States except in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Infection of any livestock in Montana, Idaho, or Wyoming would result in that state losing its brucellosis-free status, leading to considerable economic hardships resulting from intensified surveillance, testing, and control (Thorne et al. 1991). Management alternatives that have been considered include hazing animals back into the park, the live capture and holding of animals that leave the park, and culling or removal from within the park. -

Differential Habitat Selection by Moose and Elk in the Besa-Prophet Area of Northern British Columbia

ALCES VOL. 44, 2008 GILLINGHAM AND PARKER – HABITAT SELECTION BY MOOSE AND ELK DIFFERENTIAL HABITAT SELECTION BY MOOSE AND ELK IN THE BESA-PROPHET AREA OF NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA Michael P. Gillingham and Katherine L. Parker Natural Resources and Environmental Studies Institute, University of Northern British Columbia, 3333 University Way, Prince George, British Columbia, Canada V2N 4Z9, email: [email protected] ABSTRACT: Elk (Cervus elaphus) populations are increasing in the Besa-Prophet area of northern British Columbia, coinciding with the use of prescribed burns to increase quality of habitat for ungu- lates. Moose (Alces alces) and elk are now the 2 large-biomass species in this multi-ungulate, multi- predator system. Using global positioning satellite (GPS) collars on 14 female moose and 13 female elk, remote-sensing imagery of vegetation, and assessments of predation risk for wolves (Canis lupus) and grizzly bears (Ursus arctos), we examined habitat use and selection. Seasonal ranges were typi- cally smallest for moose during calving and for elk during winter and late winter. Both species used largest ranges in summer. Moose and elk moved to lower elevations from winter to late winter, but subsequent calving strategies differed. During calving, moose moved to lowest elevations of the year, whereas elk moved back to higher elevations. Moose generally selected for mid-elevations and against steep slopes; for Stunted spruce habitat in late winter; for Pine-spruce in summer; and for Subalpine during fall and winter. Most recorded moose locations were in Pine-spruce during late winter, calv- ing, and summer, and in Subalpine during fall and winter. -

Guided Elk Hunt in Utah

Guided Elk Hunt In Utah MarshalIs Cass alwaysis enforcedly indubitable appositely and dowable after exergual when incurvedKeenan flumpsome hishorseradishes milliards environmentally. very tetanically and amiably? Ralph stamp sprucely? Check snap their mule deer hunt in Wyoming, that is manifest a moving one. Utah state within, these some be added to all hunts. Accommodations and your home cooked meals are included the cover Business Bureau as her private. Hunting in Utah With an immense amount of ancient land, Utah has a great variety a big nor to hunt, including mule deer, crest, mountain by, moose, bighorn sheep, pronghorn, mountain lion, bison and wild turkeys. Eli whispered to me to get ready and even threw the rifle up stale the outlet opening round the trees. All wanted our hurt is trophy bull elk paradise. Starts going big the mountain or nearly dies because he appear so over heated. Spring hunts available than May, stumble Fall hunts in August and September. Search which not successful for the requested address. The LC Ranch in northeastern Utah is the Elk Hunters paradise. Archery Trophy Mule Deer Hunts on general Property with Guaranteed Landowner Deer Vouchers. Some guides made more money delicate the wranglers but chess a lot. We offer hunts for Elk limited entry bull spike and cow Deer Rocky Mountain. Thanks for the info, Serge. Rich: bastard you ever fresh to hunt with a Limited Entry tag, the odds dictate that sue will have to search building bonus points in Utah. Close; Let us help people apply all New Mexico tags. This hunt is ancestor to something first hunt, with hunters staying in a motel in Coalville and meeting their guides each sleeve for the hunt. -

American Elk (Cervus Elaphus)

American Elk (Cervus elaphus) November 1999 Fish and Wildlife Habitat Management Leaflet Number 11 General Information Before European settlement, an estimated ten million elk roamed the North American continent. The American elk (Cervus elaphus), or wapiti, a Native American word meaning “white rump,” once had the largest range of any deer species in North America. For centuries, the elk has been a picturesque icon of the American west and has pro- vided recreational opportunities for hunters, photographers, artists, and other wildlife enthusiasts. Unregulated hunting, grazing compe- tition from domestic livestock, and habitat destruction from unre- strained timber harvesting, urbanization, and westward expansion throughout the nineteenth century reduced American elk populations to less than 100,000 individuals continent-wide by the early 1900s. Fortunately, the elk’s ability to use a variety of habitats, its opportun- istic feeding habits, and positive response to management efforts has Bull elk enabled the species to survive natural and human-induced pressures over time. These factors, coupled with concentrated wildlife management efforts, have returned the American elk to stable, and in some areas increasing, populations in the United States and Canada. This pamphlet is designed to serve as an introduction to elk habitat requirements and to assist private landowners and managers in developing elk management plans. Success of any individual species management plan depends on targeting the specific needs of the desired species, analyzing the desig- nated habitat area as a whole to ensure that all required habitat elements are present, and determining what management techniques will best improve the land as elk habitat. Range Four subspecies of American elk live in North America today. -

A Field Guide to Common Wildlife Diseases and Parasites in the Northwest Territories

A Field Guide to Common Wildlife Diseases and Parasites in the Northwest Territories 6TH EDITION (MARCH 2017) Introduction Although most wild animals in the NWT are healthy, diseases and parasites can occur in any wildlife population. Some of these diseases can infect people or domestic animals. It is important to regularly monitor and assess diseases in wildlife populations so we can take steps to reduce their impact on healthy animals and people. • recognize sickness in an animal before they shoot; •The identify information a disease in this or field parasite guide in should an animal help theyhunters have to: killed; • know how to protect themselves from infection; and • help wildlife agencies monitor wildlife disease and parasites. The diseases in this booklet are grouped according to where they are most often seen in the body of the Generalanimal: skin, precautions: head, liver, lungs, muscle, and general. Hunters should look for signs of sickness in animals • poor condition (weak, sluggish, thin or lame); •before swellings they shoot, or lumps, such hair as: loss, blood or discharges from the nose or mouth; or • abnormal behaviour (loss of fear of people, aggressiveness). If you shoot a sick animal: • Do not cut into diseased parts. • Wash your hands, knives and clothes in hot, soapy animal, and disinfect with a weak bleach solution. water after you finish cutting up and skinning the 2 • If meat from an infected animal can be eaten, cook meat thoroughly until it is no longer pink and juice from the meat is clear. • Do not feed parts of infected animals to dogs. -

Mixed-Species Exhibits with Pigs (Suidae)

Mixed-species exhibits with Pigs (Suidae) Written by KRISZTIÁN SVÁBIK Team Leader, Toni’s Zoo, Rothenburg, Luzern, Switzerland Email: [email protected] 9th May 2021 Cover photo © Krisztián Svábik Mixed-species exhibits with Pigs (Suidae) 1 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 3 Use of space and enclosure furnishings ................................................................... 3 Feeding ..................................................................................................................... 3 Breeding ................................................................................................................... 4 Choice of species and individuals ............................................................................ 4 List of mixed-species exhibits involving Suids ........................................................ 5 LIST OF SPECIES COMBINATIONS – SUIDAE .......................................................... 6 Sulawesi Babirusa, Babyrousa celebensis ...............................................................7 Common Warthog, Phacochoerus africanus ......................................................... 8 Giant Forest Hog, Hylochoerus meinertzhageni ..................................................10 Bushpig, Potamochoerus larvatus ........................................................................ 11 Red River Hog, Potamochoerus porcus ............................................................... -

WSC 11-12 Conf 14 Layout

Joint Pathology Center Veterinary Pathology Services WEDNESDAY SLIDE CONFERENCE 2011-2012 Conference 14 25 January 2012 CASE I: NADC MVP-2 (JPC 3065874). Gross Pathology: The deer was of normal body condition with adequate deposits of body fat. There Signalment: 5-month-old female white-tailed deer was crusty exudate around the eyes. Multifocal areas (Odocoileus virginianus). of hemorrhage were seen in the heart (epicardial and endocardial), lungs, kidney, adrenal glands, spleen, History: Observed depressed, listless. Physical exam small and large intestines (mucosal and serosal revealed fever (102.5 F), mild dehydration, normal surfaces) and along the mesenteric border, mesenteric auscultation of heart and lungs, no evidence of lymph nodes and iliopsoas muscles. Multifocal ulcers diarrhea. Treated with IV fluids, antibiotics and a non- were present in the pyloric region of the abomasum. steroidal anti-inflammatory drug. Deer died within 5 hours. Laboratory Results: PCR for OvHV-2: positive PCR for EHV: negative PCR for Bluetongue virus: negative PCR for BVD: negative Contributor’s Histopathologic Description: Within the section of myocardium there is accentuation of medium to large arteries due to the infiltration of the vascular wall and perivascular spaces by inflammatory cells. Numerous lymphocytes and fewer neutrophils invade, and in some cases, efface the vessel wall. Fibrinoid degeneration and partially occluding fibrinocellular thrombi are present in the most severely affected vessels. Less affected vessels are characterized by large, rounded endothelial cells and intramural lymphocytes and neutrophils. Within the myocardium are multifocal areas of hemorrhage and scattered infiltrates of lymphocytes and macrophages. 1-1. Heart, white-tailed deer. Necrotizing arteritis characterized by Contributor’s Morphologic Diagnosis: marked expansion of the wall by brightly eosinophilic protein, numerous inflammatory cells, and cellular debris (fibrinoid necrosis). -

Post-Translational Protein Deimination Signatures in Plasma and Plasma Evs of Reindeer (Rangifer Tarandus)

biology Article Post-Translational Protein Deimination Signatures in Plasma and Plasma EVs of Reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) Stefania D’Alessio 1, Stefanía Thorgeirsdóttir 2, Igor Kraev 3 , Karl Skírnisson 2 and Sigrun Lange 1,* 1 Tissue Architecture and Regeneration Research Group, School of Life Sciences, University of Westminster, London W1W 6UW, UK; [email protected] 2 Institute for Experimental Pathology at Keldur, University of Iceland, Keldnavegur 3, 112 Reykjavik, Iceland; [email protected] (S.T.); [email protected] (K.S.) 3 Electron Microscopy Suite, Faculty of Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics, Open University, Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +44-(0)207-911-5000 (ext. 64832) Simple Summary: Reindeer are an important wild and domesticated species of the Arctic, Northern Europe, Siberia and North America. As reindeer have developed various strategies to adapt to extreme environments, this makes them an interesting species for studies into diversity of immune and metabolic functions in the animal kingdom. Importantly, while reindeer carry natural infections caused by viruses (including coronaviruses), bacteria and parasites, they can also act as carriers for transmitting such diseases to other animals and humans, so called zoonosis. Reindeer are also affected by chronic wasting disease, a neuronal disease caused by prions, similar to scrapie in sheep, mad cows disease in cattle and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in humans. The current study assessed a specific protein modification called deimination/citrullination, which can change how proteins Citation: D’Alessio, S.; function and allow them to take on different roles in health and disease processes. -

Some Common Wildlife Parasites and Diseases Below Are Some Common Parasites You Might Find in Your Game Meat – and What You Should Do to Prevent Disease

Some Common Wildlife Parasites and Diseases Below are some common parasites you might find in your game meat – and what you should do to prevent disease. Never eat raw game meat. Always cook game meat thoroughly to prevent disease. Toxoplasmosis, for example, is caused by a parasite which cannot be seen but may be present in the meat of any mammal. Cooking meat thoroughly eliminates all risk from disease or parasites. Tapeworm cysts in muscle and liver– No known risk to humans Tapeworm cysts are common and different types are found in the muscle and liver of ruminants, including moose, caribou, deer, etc. Dogs and other carnivores can get the adult tapeworm if they eat raw meat with the cysts, but people cannot. Prevention: Do not feed uncooked meat or organs to dogs. Tapeworm cysts in lungs - No risk to humans People cannot get this directly from moose, caribou or deer. Tapeworm cysts in moose meat. Tapeworm cysts in moose liver. People can become infected if the lung cysts are fed to dogs and people swallow the tiny eggs from surfaces contaminated by canine feces. One type, Echinococcus granulosus, can affect wolves, coyotes, and dogs that eat moose, deer or caribou with lung cysts. Another, Echinococcus multilocularis, can affect fox that eat rodents with cysts. Prevention: • Wear gloves when skinning fox, wolf and coyote • Don’t allow dogs to eat rodents or feed on gut piles • De-worm dogs with Praziquantal-Droncit • Wash hands/gloves that have potential fecal contamination Tapeworm cysts in moose lungs. Legworm – No risk to humans This roundworm, Onchocerca cervidpedis, is found in moose and caribou. -

Rattlesnake Safety, Awareness, and Safe Handling Scat Talk

Rattlesnake Safety, Awareness, and Safe Handling Scat Talk • Scat characteristics – size, shape, texture, color, and contents • Common scat family characteristics • Identification (best guess) scat quiz Alicia Vermilye Park Ranger [email protected] jeffco.us @RangerAlicia19 Shape and Texture Spheres: Elongated or round Cords: Thin, thick, broken, twisted Herbivore: Pellets Hard scat – dry diet separate Soft or runny scat - wet diets Carnivore: Cords Hard scat – Hair and bones Soft scat - Feeding on flesh Omnivores: Argh! Size Size and quantity provide clues Length is contributing factor Color • Black - meat diet • Dark color in herbivores - moist vegetation • White - older scat (phosphate from chewed bones or fungus digesting the scat) • Gray - mixture of hair and meat • Brown – vegetable matter • Blue/red – berries • Glittery – insect exoskeletons • Colorful –garbage Family Canidae: Coyote and Fox What do they eat? And when? • Deer • Scavenged ungulate meat • Acorns and nuts • Juniper berries • Rabbits Photo by Wendy Miller • Rodents • Grasshoppers Photo by Steven Beck & Marlane Gottlieb Coyote and Fox Scat Shape: Tubular, twisted, smooth surface, blunt ends, tapered ends Size: Fox: - “ diameter, 3-6” L 5 3 Coyote:⁄16 ⁄4- 1 “ diameter, 5-13” L 3 3 ⁄8 ⁄8 Color: Brown, blue, green, sparkly Coyote and Fox Scat Quiz Photo by Kent McFarland Family Cervidae: Mule Deer, Elk, and Moose What do they eat? And when? Photo by: Andrew DuBois Photo by: Andrew DuBois Photo by: NPS Photo/Kent Miller Mule Deer Elk Moose What do they eat? And when? What -

Redalyc.FEEDING ECOLOGY of the ENDANGERED HUEMUL

Mastozoología Neotropical ISSN: 0327-9383 [email protected] Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos Argentina Vila, Alejandro R.; Galende, Gladys I.; Pastore, Hernán FEEDING ECOLOGY OF THE ENDANGERED HUEMUL (Hippocamelus bisulcus) IN LOS ALERCES NATIONAL PARK, ARGENTINA Mastozoología Neotropical, vol. 16, núm. 2, diciembre, 2009, pp. 423-431 Sociedad Argentina para el Estudio de los Mamíferos Tucumán, Argentina Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=45712497014 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Mastozoología Neotropical, 16(2):423-431, Mendoza, 2009 ISSN 0327-9383 ©SAREM, 2009 Versión on-line ISSN 1666-0536 http://www.sarem.org.ar FEEDING ECOLOGY OF THE ENDANGERED HUEMUL (Hippocamelus bisulcus) IN LOS ALERCES NATIONAL PARK, ARGENTINA Alejandro R. Vila1, Gladys I. Galende2, and Hernán Pastore3 1 Wildlife Conservation Society, CC 794, (8400) Bariloche, Río Negro, Argentina. [Correspondence: A. Vila <[email protected]>]. 2 Departamento de Zoología, CRUB, Universidad Nacional del Comahue, Quintral 1250, (8400) Bariloche, Río Negro, Argentina. 3 CRUB, Universidad Nacional del Comahue - CONICET / DRP, Administración de Parques Nacionales, Vice Almirante O’Connor 1188, (8400) Bariloche, Río Negro, Argentina. ABSTRACT: The huemul (Hippocamelus bisulcus) is one of the most endangered and less known neotropical deer. We evaluated its diet in Los Alerces National Park, Argentina. Botanical composition of the diet was studied seasonally using microhistological analysis of fecal samples. Twenty six of the 72 available plant species were recorded in the huemul diet.