Download Article Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Grade 4 Library Week 5 Butterfly Lion Book Promotion Dear Grade 4S and Your Parents Every Year in Grade 4 Library, I Do

Grade 4 Library Week 5 Butterfly Lion book promotion Dear Grade 4s and your Parents Every year in Grade 4 library, I do a book promotion of Butterfly Lion by Michael Morpurgo Michael Morpurgo is a very highly regarded writer for children and I particularly love to promote this book as it has links to South Africa and the famous white lions of Timbavati. So first, I will take you to Michael Morpurgo’s official website …. https://www.michaelmorpurgo.com/ Whenever I go onto a website like this, I first look at all the books the author has written and boy, Michael Morpurgo has written many! Then I like to find out about the author’s life, which you can do here: https://www.michaelmorpurgo.com/about-michael-morpurgo/ So why do I choose to recommend Butterfly Lion to grade 4s? Well, it is actually a story within a story. It starts with a boy Michael, who runs away from his boarding school. He comes across a house and meets the old woman, Millie, who lives there. She tells him an amazing story about a boy and a white lion who became friends. This story takes place in southern Africa and is the story of a young boy who rescues an orphaned white lion cub from the African bush. They remain inseparable until Bertie has to go away to boarding school and the lion is sold to a circus. Years later they are reunited, until the lion gently dies of old age. Here is the author himself reading chapter one of Butterfly Lion, so this will give you a taste of the story: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YVQd2li8CgQ The white lion cub that Bertie befriends is based on the true fact that rare white lions have been observed for many years in the Timbavati area, near Kruger Park. -

White Lions: Reintroduction to Their Natural and Spiritual Homelands

White Lions: Reintroduction to Their Natural and Spiritual Homelands Linda Tucker Abstract—The Global White Lion Protection Trust is committed bushveld to our rescue. Amazingly, the lions seemed to calm to establishing the White Lions both as South Africa’s national down at her arrival. treasure and as a global heritage. All conservation issues today are After this mind-altering experience—which, as you global issues. With many species, including many of the big cats, can imagine, put everything else in my life in instant on the brink of extinction, urgent conservation measures need to be perspective—I gave up my high-powered advertising job in implemented to ensure their survival. The White Lions were born in London, and returned to my childhood haunt of Timbavati one place only—the Timbavati region—but were artificially removed and to Maria Khosa, who became my teacher. It was this because of their beauty and rarity. After 13 years of extinction in lion-hearted woman who taught me that the key to hu- the wild, the Trust has initiated a world-first reintroduction of the mankind’s relationship with wilderness is two-fold: LOVE White Lions to their unique endemic range, based on scientific and RESPECT. Through these two profoundly simple techniques of social bonding the White Lions with resident tawny principles, all the balance of nature can be maintained, lions, following successful lion reintroduction methods tried and and humankind has nothing to fear from wilderness and tested in a number of reserves (Van Dyk 1997). It is our hope that our natural environment. -

Headlines Most Added Lorraine Wraps up the Pd Gig at Waqx 1

THE 4 Trading Post Way Medford Lakes. New Jersey 08055 HARD REPORT April 1, 1988 Issue #72 609-654-7272 FRONTRUNNERS NEIL YOUNG SCORPIONS "TEN MEN WORKIN' " "RHYTHM OF LOVE" "Neil has succeeded over "We've been waiting for it for the years with a wide range months, and we're knocked of musical directions, but out on first listen. It's heavy his most flattering style out of the box, with the could prove to be this Monsters Of Rock' Tour blues -based horn -soaked making it an even bigger assassin of a song". .. event".. Lin Brehmer, WXRT Reprise Mercury Pam Edwards, KGB -FM DIVINYLS RECORD OF THE WEEK "THE FLAME" "BACK TO THE WALL" Cheap Trick Of this week's #1 Most Added LAP OF LUXURY Including: track WVNF's Charlie Logan Ms. Amphlett may be the The Flame/All We Need Is A Dream only female rocker with Ghost Town/Let Go says, "This is just a marvelous pipes that could peel paint, song that will return Cheap but Mike Chapman has Trick to its rightful position as finally given them the moves to cross rock to pop. one of the best bands in the Chry universe". Epic NEW PLAY PRIORITIES... ZIGGY MARLEY PAT McLAUGHLIN IRON MAIDEN JETHRO TULL 10,000 MANIACS JETHRO TULL CREST OF A KNAVEK. Including' Steel Monkey/Farm On The Freeway Jump Start "Tomorrow People'. (Virgin) "No Problem" (Capitol) ' Can IPlay (Capitol) "Budapest" (Chrysalis) "Like The Weather" (Elektra) CHARTSTARS HEADLINES MOST ADDED LORRAINE WRAPS UP THE PD GIG AT WAQX 1. Cheap Trick "The Flame" Epic 88 2. -

Download Honestly: My Life and Stryper Revealed Free Ebook

HONESTLY: MY LIFE AND STRYPER REVEALED DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Michael Sweet, Dave Rose, Doug Van Pelt | 286 pages | 06 May 2014 | Big3 Records | 9780996041805 | English | none Michael Sweet – "I’m Not Your Suicide": Hard Rock Daddy Review This might have something to do with the acoustics of the venue. For me, the best times musically came during the seventies and eighties. Robert: Brian is also an amazing guitar player, as well as a drummer. AXS: Stryper recently kicked off the U. Newer Posts Older Honestly: My Life and Stryper Revealed Home. While Stryper gambled on a more polished sound in and met with limited success, will this gamble on harder sounding album 30 years later be more successful? It exploded, had five number ones and made the cover of CCM Magazine, but at the same time, the label was hurting, and by the time I did Real, they were getting ready to close their doors. It was short lived, but they're very nice people and we get to see them over and over again…Blissed was a wonderful time re-vamping myself and coming alive again in the early s. Was that the Honestly: My Life and Stryper Revealed process you used for God Damn Evil? Why so Honestly: My Life and Stryper Revealed people have declared Michael Sweet a significant influence on their lives; from Larry the Cable Guy to professional wrestler Chris Jericho to Haitian musician and politician Wyclef Jean and more. Share on Facebook. The guitarist The first Christian rock band to see chart-topping success on MTV, Stryper went on to see over 10 million albums and has sold out arenas all over the world. -

Heavy Metal Band Names

320938_Text_v3.qxd:. 7/15/10 5:13 PM Page 84 84 HEAVY METAL BAND NAMES HEAVY METAL IS A GENRE OF ROCK distinctive names. Heavy metal bands view this darkness as FIGURE 1: WHAT IS HEAVY METAL REBELLING AGAINST? for its loudness, machismo, and theatricality. So complete and inescapable. Not only do they talk it’s no wonder that heavy metal band names are about the darkness in everyday life—Venom, similarly theatrical. What is perhaps unexpected is Poison, Anthrax, Anal Apocalypse—they go on to their universally pessimistic slant. You would think assure viewers that there is no light in the afterlife. being in a heavy metal band is fun: rocking out, hanging with the guys, scoring groupies. Yet most A large percentage of heavy metal band names are heavy metal names focus on the negative: death, open criticisms of modern culture (see Figure 1: darkness, and rampant misspelling. What is Heavy Metal Rebelling Against?), but their favorite thing to rebel against is definitely Of all the band name charts I’ve drawn(1), heavy organized religion, because it accomplishes mul- metal band names are the most homogenous in tiple goals. their philosophical worldview. Blackness and dark- ness are the prevailing themes of heavy metal band 1. It’s easy to make fun of God, because ever since the New Testament, he usually turns the 3. You gotta rebel against something. Why not (1) A cappella, Acid jazz, Adai-adai, Ambient, Anti-folk, other cheek. religion? Appalachia, Bamboo band, Bob Marley tribute bands, Calypso, Celtic Reggae, Delta Blues, Doo wop, Dubtronica, Emo, Ethereal Wave, Futurepop, Garage 2. -

Ebook Download Saving the White Lions: One Womans Battle For

SAVING THE WHITE LIONS: ONE WOMANS BATTLE FOR AFRICAS MOST SACRED ANIMAL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Linda G. Tucker | 374 pages | 10 Jun 2013 | North Atlantic Books,U.S. | 9781583946053 | English | Berkeley, CA, United States Saving the White Lions: One Womans Battle for Africas Most Sacred Animal PDF Book The rare white lion Mufasa has a home in Rustenburg's Wild for Life rehabilitation center since , when his pet owners held him without proper papers. Be Sociable, Share! They were born to a tawny lioness, demonstrating the gene still survives in the wild. You can opt-out using your browser settings, but the site will not work correctly, in particular the shopping cart. Their value as attractions may well send them down the same path as the white Bengal tiger: mass production, inbreeding and indiscriminate crossing with other subspecies e. Please login or join to leave a comment. About the author. In addition to the spectacular photos, Christo and Wilkinson share their memoirs of their expeditions to Africa, Asia and the Arctic, as they witness the dangers these endangered species face. June While accounts of white lions have been around for centuries, they were dismissed as superstition. White lions, also known as blond lions, are not albino, but are leucistic and are uncommon in the wild as they lack normal camouflage. Tucker, Linda. Females realize 4. At the age of about 2 years, this female left the Timbavati reserve and was unfortunately killed. Gurche gets his reference from fossil remains, as well as comparative ape and human anatomy studies. In March a female lion with 3 white cubs was observed neat Tshokwane. -

December 26 2018 German Release Date: January 31 2018

GALATÉE FILMS, OUTSIDE FILMS and STUDIOCANAL present FRENCH RELEASE DATE: DECEMBER 26 2018 GERMAN RELEASE DATE: JANUARY 31 2018 Run time: 1h 37 INTERNATIONAL PUBLICITY CONTACTS Alexandre Bourg [email protected] Erin Wellings [email protected] Tel: +44 (0)20 7534 2700 SYNOPSIS Ten year old Mia has her life turned upside down when her family decides to leave London to manage a lion farm in Africa. When a beautiful white lion, Charlie, is born, Mia finds happiness once again and develops a special bond with the growing cub. When Charlie reaches three, Mia’s life is rocked once again as she uncovers an upsetting secret kept hidden by her father. Distraught by the thought that Charlie could be in harm, Mia decides to run away with him. The two friends set out on an incredible journey across the South African savanna in search of another land where Charlie can live out his life in freedom. GILLES DE MAISTRE INTERVIEW Director Where did the idea for the story come from? It goes back years. I shot a series about children around the world who have deep bonds with wild animals for a French television documentary. My research took me to South Africa, where I filmed a child whose parents had a lion-breeding farm. They bred lions for conservation purposes - or so they claimed. The end goal was to sell them on to zoos and wildlife parks, to celebrate the king of animals in all its glory, and sometimes even to rewild them. There was a 10-year-old boy there who was in love with the lions. -

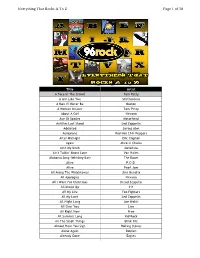

Of 30 Everything That Rocks a to Z

Everything That Rocks A To Z Page 1 of 30 Title Artist A Face In The Crowd Tom Petty A Girl Like You Smithereens A Man I'll Never Be Boston A Woman In Love Tom Petty About A Girl Nirvana Ace Of Spades Motorhead Achilles Last Stand Led Zeppelin Addicted Saving Abel Aeroplane Red Hot Chili Peppers After Midnight Eric Clapton Again Alice In Chains Ain't My Bitch Metallica Ain't Talkin' About Love Van Halen Alabama Song (Whiskey Bar) The Doors Alive P.O.D. Alive Pearl Jam All Along The Watchtower Jimi Hendrix All Apologies Nirvana All I Want For Christmas Dread Zeppelin All Mixed Up 311 All My Life Foo Fighters All My Love Led Zeppelin All Night Long Joe Walsh All Over You Live All Right Now Free All Summer Long Kid Rock All The Small Things Blink 182 Almost Hear You Sigh Rolling Stones Alone Again Dokken Already Gone Eagles Everything That Rocks A To Z Page 2 of 30 Always Saliva American Bad Ass Kid Rock American Girl Tom Petty American Idiot Green Day American Woman Lenny Kravitz Amsterdam Van Halen And Fools Shine On Brother Cane And Justice For All Metallica And The Cradle Will Rock Van Halen Angel Aerosmith Angel Of Harlem U2 Angie Rolling Stones Angry Chair Alice In Chains Animal Def Leppard Animal Pearl Jam Animal I Have Become Three Days Grace Animals Nickelback Another Brick In The Wall Pt. 2 Pink Floyd Another One Bites The Dust Queen Another Tricky Day The Who Anything Goes AC/DC Aqualung Jethro Tull Are You Experienced? Jimi Hendrix Are You Gonna Be My Girl Jet Are You Gonna Go My Way Lenny Kravitz Armageddon It Def Leppard Around -

Frontrunners Headlines

THE 4 Trading Post Way Medford Lakes. New Jersey 08055 HARD REPORT February 26, 1988 Issue #67 609-654-7272 alb FRONTRUNNERS THE DEL -LORDS JUDAS PRIEST "JUDAS KISS" "JOHNNY B. GOODE" "The best new record I've Watch this incredible heard in years-and one interpretation emerge as play a lot-from a band / the biggest cover tune of probably wouldn't have the first quarter-and one walked across the street to of the biggest hits of this see before".. band's career. ... Russ Mottla, KTYD Atlantic Enigma KINGDOM COME RECORD OF THE WEEK "KINGDOM COME" ROBERT PLANT KINGDOM "Considering they're a band new on the scene, this "NOW AND ZEN" COME is without a doubt the most With an a/bum debut at 1*, all kinds explosive thing I've of instant request activity, pages of participated in in my 17 programmer raves and five more years in radio". ... ofiej4v.charted tracks-it's obvious this is Bruce McGregor, WRIF the biggest thing to date in '88.... Polydor E s Pa r a nz a / At I NEW PLAY PRIORITIES... JONI GEORGE ROBERT DWEEZIL THOROGOOD PALMER ZAPPA MSG MITCHELL ERT PALMER MOOG JONI MITCHELL "Born To Be Bad" (EMI/Manhattan) "Sweet Lies" (Island) ' My Guitar (Chrysalis) 'Follow The Night" (capitol)"Snakes And Ladders" (Geffen) CHARTSTARS HEADLINES MOST ADDED SALE OF NBC RADIO GETS $121.5 MILLION 1. Robert Plant "Tall Cool One" EsParanza/Atl 91 LONE STAR LISLE TO DO MORNINGS AT KISW 2. B. Springsteen "All That Heaven . ." Columbia 52 3. Robert Plant "Ship Of Fools" EsParanza/Atl 47 11 MILLION DOLLAR DEAL: KSJO FOR SALE BIGGEST MOVERS RANDY CRITTENTON SIGNS WITH DB RECORDS B. -

MIKE TRAMP's WHITE LION Last Roar (Hard Rock)

MIKE TRAMP'S WHITE LION Last roar (Hard Rock) Année de sortie : 2004 Nombre de pistes : 64 Durée : 12' Support : CD Provenance : Reçu du label Le chanteur danois Mike TRAMP fut dans les années 80’ et début 90’ le talentueux chanteur du groupe américain WHITE LION. Quatre albums couronnèrent la trop courte carrière d’un groupe resté dans les mémoires du hard rock et des hard rockers. Hyper inspirés, Fight To Survive (1985), Pride (1987), Big Game (1989), Mane Attraction (1991) imposèrent le Lion Blanc parmi l’élite et révélèrent un guitariste d’exception, M. Vito BRATTA. La section rythmique était quant à elle composée de James LORENZO à la basse et Greg D’ANGELO aux baguettes. Les meilleures choses devant apparemment connaître une fin, M. Vito BRATTA disparu de la circulation et Mike TRAMP poursuivit sa carrière avec FREAK KITCHEN et en publiant régulièrement des albums solos. La section rythmique se fit entendre aussi sur diverses réalisations. Mike TRAMP décida pour sa part, en l’année 1999 de réenregistrer, avec des musiciens amis, cette rétrospective composée de 12 covers repensés de bien belle manière. Les esprits dérangés crieront à la démarche mercantile et se tromperont sur toute la ligne. Car ce Last Roar, enfin disponible chez nous, respire la sincérité, le talent et l’inspiration. Les compositions de départ du duo TRAMP / BRATTA respirent la mélodie et la classe et s’attaquer à ce patrimoine aurait pu être un combat de trop. Mais le lion voulait encore rugir et le boulot de TRAMP et ses amis mérite un grand respect. -

Global White Lion Protection Trust White Lion Conservation Project

Global White Lion Protection Trust White Lion Conservation Project A Solution Based Approach -Linda Tucker “No-one in their right mind would ever travel to Siam and there murder the rare White Elephants that we find in that country. But people come to South Africa to brutally murder the White Lions of Timbavati in the name of manliness and in the name of sport. The sacred icons of other races and nations in this world are respected, revered and protected. But the icons of Africa are massacred with cold impunity” -Credo Mutwa Engaging the South African Government, Communities, Parks and Tourism 2003 -2008 WLT Representatives • Linda Tucker: –MA CANTAB from Cambridge University (1987) –Author “Mystery of the WhiteLions”( 2001) –Founder Global White Lion Protection Trust (2002) • Jason Turner: –MSc Wildlife Management -University of Pretoria (2005) –White Lion Ecologist and Scientific Advisor –Head of White Lion Reintroduction –Professional Memberships: •Member Cat Specialist Group •Member African Lion Working Group •Member Conservation Breeding Specialist Group •Member SA Veterinary Association • Wendy Strauss: –BA (Hons) –University of the Witwatersrand (1992) –MA Mass Communication –Leicester University (2000) –Senior Communications Partner –Head of White Lion Community Development and Heritage Mission Statement The protection of the White Lions, their endemic land and their cultural heritage in perpetuity through science and sacred science. International Congresses •World Wilderness Congress(2001), •World Summit of Sustainable Utilization