About the Chesapeake Bay (Source

Total Page:16

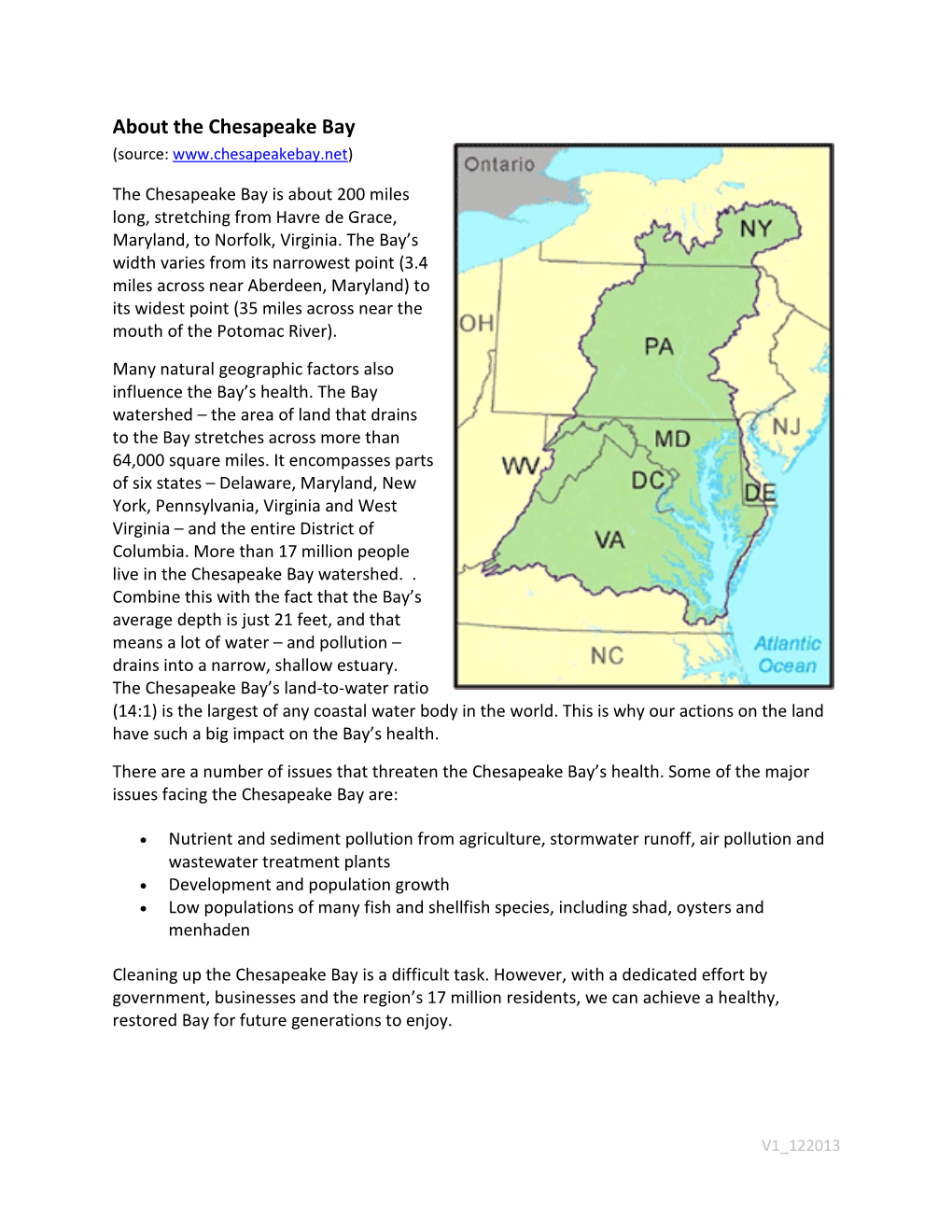

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upper Cenozoic Deposits of the Central Delmarva Peninsula, Maryland and Delaware

Upper Ceoozoic Deposits GEOLOGICAL SXJEVilY FRQfEBSIONAL lAPEE Upper Cenozoic Deposits of the Central Delmarva Peninsula, Maryland and Delaware By JAMES P. OWENS and CHARLES S. DENNY SURFACE AND SHALLOW SUBSURFACE GEOLOGIC STUDIES IN THE EMERGED COASTAL PLAIN OF THE MIDDLE ATLANTIC STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1067-A Upper Tertiary deltaic and shallow-water marine deposits form the backbone of the peninsula. The oldest marine deposits of Pleistocene age reach a maximum altitude of 15 meters (50 feet) and have been dated radiometrically at about 100,000 years UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1979 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR CECIL D. ANDRUS, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY H. William Menard, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Owens, James Patrick, 1924- Upper Cenozoic deposits of the central Delmarva Peninsula, Maryland and Delaware. (Surface and shallow subsurface geologic studies in the emerged coastal plain of the Middle Atlantic States) (Geological Survey professional paper ; 1067-A) Bibliography: p. Includes index. Supt. of Docs, no.: I 19.16:1067-A 1. Geology, Stratigraphic Cenozoic. 2. Geology Delmarva Peninsula. I. Denny, Charles Storrow, 1911- joint author. II. Title. III. Series. IV. Series: United States. Geological Survey. Professional paper ; 1067-A. QE690.093 551.7'8 77-608325 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 Stock Number 024-001-03191-4 CONTENTS Abstract._____________________________________________________________ -

2012-AG-Environmental-Audit.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER ONE: YOUGHIOGHENY RIVER AND DEEP CREEK LAKE .................. 4 I. Background .......................................................................................................... 4 II. Active Enforcement and Pending Matters ........................................................... 9 III. The Youghiogheny River/Deep Creek Lake Audit, May 16, 2012: What the Attorney General Learned............................................................................................. 12 CHAPTER TWO: COASTAL BAYS ............................................................................. 15 I. Background ........................................................................................................ 15 II. Active Enforcement Efforts and Pending Matters ............................................. 17 III. The Coastal Bays Audit, July 12, 2012: What the Attorney General Learned .. 20 CHAPTER THREE: WYE RIVER ................................................................................. 24 I. Background ........................................................................................................ 24 II. Active Enforcement and Pending Matters ......................................................... 26 III. The Wye River Audit, October 10, 2012: What the Attorney General Learned 27 CHAPTER FOUR: POTOMAC RIVER NORTH BRANCH AND SAVAGE RIVER 31 I. Background ....................................................................................................... -

Shoreline Management in Chesapeake Bay C

Shoreline Management In Chesapeake Bay C. S. Hardaway, Jr. and R. J. Byrne Virginia Institute of Marine Science College of William and Mary 1 Cover Photo: Drummond Field, Installed 1985, James River, James City County, Virginia. This publication is available for $10.00 from: Sea Grant Communications Virginia Institute of Marine Science P. O. Box 1346 Gloucester Point, VA 23062 Special Report in Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering Number 356 Virginia Sea Grant Publication VSG-99-11 October 1999 Funding and support for this report were provided by... Virginia Institute of Marine Science Virginia Sea Grant College Program Sea Grant Contract # NA56RG0141 Virginia Coastal Resource Management Program NA470Z0287 WILLIAM& MARY Shoreline Management In Chesapeake Bay By C. Scott Hardaway, Jr. and Robert J. Byrne Virginia Institute of Marine Science College of William and Mary Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062 1999 4 Table of Contents Preface......................................................................................7 Shoreline Evolution ................................................................8 Shoreline Processes ..............................................................16 Wave Climate .......................................................................16 Shoreline Erosion .................................................................20 Reach Assessment ................................................................23 Shoreline Management Strategies ......................................24 Bulkheads and Seawalls -

Chesapeake Bay Restoration: Background and Issues for Congress

Chesapeake Bay Restoration: Background and Issues for Congress Updated August 3, 2018 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45278 SUMMARY R45278 Chesapeake Bay Restoration: Background and August 3, 2018 Issues for Congress Eva Lipiec The Chesapeake Bay (the Bay) is the largest estuary in the United States. It is Analyst in Natural recognized as a “Wetlands of International Importance” by the Ramsar Convention, a Resources Policy 1971 treaty about the increasing loss and degradation of wetland habitat for migratory waterbirds. The Chesapeake Bay estuary resides in a more than 64,000-square-mile watershed that extends across parts of Delaware, Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia. The Bay’s watershed is home to more than 18 million people and thousands of species of plants and animals. A combination of factors has caused the ecosystem functions and natural habitat of the Chesapeake Bay and its watershed to deteriorate over time. These factors include centuries of land-use changes, increased sediment loads and nutrient pollution, overfishing and overharvesting, the introduction of invasive species, and the spread of toxic contaminants. In response, the Bay has experienced reductions in economically important fisheries, such as oysters and crabs; the loss of habitat, such as underwater vegetation and sea grass; annual dead zones, as nutrient- driven algal blooms die and decompose; and potential impacts to tourism, recreation, and real estate values. Congress began to address ecosystem degradation in the Chesapeake Bay in 1965, when it authorized the first wide-scale study of water resources of the Bay. Since then, federal restoration activities, conducted by multiple agencies, have focused on reducing pollution entering the Chesapeake Bay, restoring habitat, managing fisheries, protecting sub-watersheds within the larger Bay watershed, and fostering public access and stewardship of the Bay. -

New York Buffer Action Plan

Chesapeake Bay Buffer Action Strategy for New York Current Effort Based on the targets set in New York’s Phase III Watershed Implementation Plan, New York plans to implement 2,606 acres of forest buffer and 1,020 acres of grass buffers in the agriculture sector by 2025. In the urban sector, New York plans to implement 3,095 acres of forest buffer and 1,853 acres of tree planting by 2025. Table 1 shows the current progress in 2020 towards achieving riparian forest buffer targets, the percent achieved, and acres remaining. Table 1 Amount of riparian forest buffer and tree plantings to achieve NY’s WIP III. Best Management Practice 2020 WIP III Percent Acres Acres Progress (acres) Achieved Remaining Needed (acres) per Year Pasture Forest Buffers 2,058 3,543 58% 1,485 297 Pasture Grass Buffers 1,166 1,815 64% 649 130 Cropland Forest Buffers 1,003 2,124 47% 1,121 224 Cropland Grass Buffers 405 776 52% 371 74 Urban Forest Buffers 37 3,132 1% 3,095 619 Opportunities for Implementation Participating Partners New York’s key partners in buffer implementation are the Department of Environmental Conservation, Department of Agriculture and Markets, Upper Susquehanna Coalition, and Soil and Water Conservation Districts. Partners to be further engaged include Farm Service Agency, National Resources Conservation Service, local communities, nongovernment organizations, land trusts and members of the Climate Action Council. Strategy for Implementation As outlined in the Phase III WIP, New York proposes the following strategies to improve its riparian buffer delivery including increase voluntary implementation, explore new funding strategies, sustaining motivation and continuing to support technical capacity. -

Report on the Early History of the Alexandria, Virginia Sewerage System

Report on the Early History of the Alexandria, Virginia Sewerage System Jason Tercha January 16, 2017 In 1952, the Alexandria City Council created the first sanitation authority in Virginia. Four years later, the City of Alexandria Sewer Authority opened a water-treatment facility near the mouth of Hooff’s Run. Since 1956, the water treatment facility has treated the city’s sewerage discharge, purifying the sanitary water of the city and discharging clean water back into the environment. In response to more stringent environmental standards and renewed efforts to restore the health of the Chesapeake Bay, the Alexandria Sewer Authority upgraded the facility during the late 1990s and through the 2000s. Now known as Alexandria Renew Enterprises after a 2012 rebrand, the sewerage facility remains a crucial component of the city of Alexandria’s efforts to maintain the health and prosperity of its citizens and environment. This brief overview of the city of Alexandria’s twentieth and twenty-first century efforts to manage and treat its sewerage is well documented in city records, newspapers, and the annual reports of the Alexandria Sewer Authority.1 However, as much as these recent efforts to manage waste- and stormwater are known, the city’s earlier struggles to accomplish these goals have largely remained a mystery. The obscurity of Alexandria’s early sewerage control efforts might mistakenly suggest a dearth of water management efforts in the nineteenth century. As this report demonstrates, since the city’s founding Alexandrians exerted immense efforts to manage the excess stormwater and to dispose of the human and animal wastes by incorporating new technologies and practices to respond to evolving knowledge of human health and the environment of a growing regional entrepôt. -

Module 1 Overview

Module 1 Educator’s Guide Overview What’s up with Geography Standards World in Spatial Terms Earth’s water • Standard 1: How to use maps and other geographic representations, tools, and technologies to acquire, resources? process, and report information from a spatial perspective Places and Regions Module Overview • Standard 4: The physical and This module addresses issues that are of human characteristics of places fundamental importance to life. Four case Physical Systems studies of a coastal bay, an inland sea, a river, and mountain snow pack • Standard 7: The physical pro- investigate water resources important to millions of people in North cesses that shape the patterns of America, Asia, and Africa. Each investigation focuses on the physical Earth’s surface nature of the resource, how humans depend upon the resource, and how • Standard 8: Characteristics and human use affects the resource creating both problems and opportunities. distribution of ecosystems Environment and Society Investigation 1: Chesapeake Bay: Resource use or abuse? • Standard 14: How humans modify Students play roles of concerned citizens, public officials, and scientists the physical environment • while learning about the Chesapeake Bay and its environs. They use data Standard 15: How physical and satellite images to examine how human actions can degrade, im- systems affect human systems prove, or maintain the quality of the bay in order to make policy recom- The Uses of Geography • Standard 18: How to apply mendations for improving this resource for future use. geography to interpret the present and plan for the future Investigation 2: What is happening to the Aral Sea? Students work as teams of NASA geographers using satellite images to measure the diminishing size of the Aral Sea. -

Shoreline Evolution Chesapeake Bay Shoreline City of Norfolk, Virginia

Shoreline Evolution Chesapeake Bay Shoreline City of Norfolk, Virginia Virginia Institute of Marine Science College of William & Mary Gloucester Point, Virginia 2005 Shoreline Evolution Chesapeake Bay Shoreline City of Norfolk, VA C. Scott Hardaway, Jr. 1 Donna A. Milligan 1 Lyle M. Varnell 2 Christine Wilcox 1 George R. Thomas 1 Travis R. Comer 1 Shoreline Studies Program 1 Department of Physical Sciences and Wetlands Program 2 Center for Coastal Resources Management Virginia Institute of Marine Science College of William & Mary Gloucester Point, Virginia 2005 This project was funded by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality’s Coastal Resources Management Program through Grant #NA17OZ2355 of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, under the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of NOAA or any of its subagencies or DEQ. LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1. Location of the City of Norfolk within the Chesapeake Bay estuarine system...................2 Figure 2. Location of localities in the Dune Act with jurisdictional and non-jurisdictional localities noted. ...2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Figure 3. Geological map of the City of Norfolk (from Mixon et al., 1989). ...........................3 Figure 4. Index of shoreline plates.............................................................4 TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................. i Figure 5. Variability of dune and beach profiles within the City of Norfolk ............................7 Figure 6. Typical profile of a Chesapeake Bay dune system. ........................................7 LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................... i Figure 7. Photo of the Norfolk shoreline showing dune site NF3.. ...................................9 Figure 8. -

Garrett County

Appendix D- Recreation Inventory County Acres Private/ quasi-public State/Federal Acres Courts Fields Trails (Miles) Campsites Basketball Basketball Baseball Multi Swimming XC Golf Public Beach Public Boat Site Recreation Resource Recreation Resource Recreation Resource Classification Ownership Comments/Amenities Indoor Outdoor Tennis Other Gymnasium Softball Soccer Purpose Pools Skiing Hiking Biking ORV Snowmobile Total Public Pvt Courses (ft.) Launch Areas Accident Community Park East 4.1 Neighborhood Park Town of Accident Ball field, walking trail, horseshoe pits 1 1 1 0.25 0.25 Accident Community Park West 12.5 Neighborhood Park Town of Accident Pavilions, volleyball Accident Elementary School 9.6 School Recreation Park Board of Education Basketball court, playground 1 1 1 1 Accident Community Pond 2.4 Community Park Town of Accident Fishing pond Aquatic Center 1.0 Marine Private Private marina 1 ASCI -Adventure Sports Center Int'l. 17.0 Special Use Area ASCI Man-made whitewater course Avilton Community Center 2.0 Special Use Area Avilton Community Assoc. Playground, basketball court, pavilion 1 Bear Creek Hatchery Fish Mgmt. Area 113.0 Natural Resource Area State of MD Fish management area Big Run State Park 300.0 State Park State of MD Camping, fishing, Savage River Reservoir access 29 1 Bill's Outdoor Center 1.0 Marine Private Lake access, shoreline Bills Marine Service, Inc. 1.0 Marine Private Marina, boat rentals 1 Bloomington Fire Co. Town Park 3.0 Community Park Bloomington Fire Co. Basketball court, walking trail, pavilion -

The Recreation the Delmarva Peninsula by David

THE RECREATION POTENTIAL OF THE DELMARVA PENINSULA BY DAVID LEE RUBIN S.B., Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1965) SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOT THE DEGREE OF MASTER IN CITY PLANNING at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June, 1966 Signature of Author.,.-.-,.*....... .. .*.0 .. .. ...... .. ...... ... Department of City and Regional Planning May 23, 1966 Certified by.... ....... .- -*s.e- Super....... Thesis Supervisor Accepted by... ... ...tire r'*n.-..0 *10iy.- .. 0....................0 Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students 038 The Recreation Potential of the Delmarva Peninsula By David Lee Rubin Submitted to the Department of City and Regional Planning on 23 May, 1966 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning. rhis thesis is a plan for the development of Lne recreation potential of the Delmarva Peninsyla, the lower counties of Delaware and the Eastern Shore of Maryland and Virginia, to meet the needs of the Megalopolitan population. Before 1952, the Delmarva Peninsula was isolated, and no development of any kind occurred. The population was stable, with no in migration, and the attitudes were rural. The economy was sagging. Then a bridge was built across the Chesapeake Bay, and the peninsula became a recreation resource for the Baltimore and Washington areas. Ocean City and Rehoboth, the major resorts, have grown rapidly since then. In 1964, the opening of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel further accellerated growth. There are presently plans for the development of a National Seashore on Assateague Island, home of the Chincoteague ponies, as well as state parks along the Chesapeake Bay, and such facilities as a causeway through the ocean and a residential complex in the Indian River Bay. -

Environmental Literacy in Delaware

DELAWARE CHESAPEAKE BAY WATERSHED PORTION Environmental Literacy in Delaware Why environmental literacy? How does Delaware compare to the The well-being of the Chesapeake Bay watershed Chesapeake Bay watershed? will soon rest in the hands of its youngest citizens: 2.7 Environmental Literacy Planning: School districts’ self-identified preparedness million students in kindergarten through twelfth grade. to put environmental literacy programs in place Establishing strong environmental education programs Delaware now provides a vital foundation for these future stew- 63% 25% 13% ards. Chesapeake Bay watershed Along with Maryland, Pennsylvania, Virginia and 9% 24% 8% 59% Washington, D.C., Delaware has committed to helping Well-prepared Somewhat prepared its students graduate with the knowledge and skills Not prepared Non-reporting needed to act responsibly to protect and restore their local watersheds. They will do this through: Meaningful Watershed Educational Experiences (MWEEs): School districts that reported providing MWEEs to their students • Environmental Literacy Planning: Developing a MWEE Availability in Elementary Schools comprehensive and systemic approach to environ- Delaware mental literacy for students that includes policies, 13% 25% 50% 13% practices and voluntary metrics. Chesapeake Bay watershed • Meaningful Watershed Educational Experiences 16% 13% 11% 59% (MWEEs): Continually increasing students’ under- MWEE Availability in Middle Schools standing of the watershed through participation in Delaware teacher-supported Meaningful Watershed Edu- 50% 13% 25% 13% cational Experiences and rigorous, inquiry-based Chesapeake Bay watershed instruction. 18% 14% 9% 59% MWEE Availability in High Schools • Sustainable Schools: Continually increasing the number of schools that reduce the impact of their Delaware buildings and grounds on the environment and 25% 25% 38% 13% human health. -

Strategies for Financing Chesapeake Bay Restoration in New York State

StrategiesPrepared by the for University Financing of Maryland Chesapeake Environmental Bay Finance Center and the Syracuse University Environmental Finance RestorationCenter for the Chesapeake in New YorkBay Program State Office and the State of New York February 2019 efc.umd.edu efc.syr.edu Prepared by the University of Maryland Environmental Finance Center and the Syracuse University Environmental Finance Center for the Chesapeake Bay Program Office and the State of New York March 2019 efc.umd.edu efc.syr.edu - 1 - This report was prepared by the Environmental Finance Center at the University of Maryland (UMD-EFC) and the Syracuse University Environmental Finance Center (SU-EFC), with funding from the US EPA Chesapeake Bay Program Office. The EFC project team included Kristel Sheesley, Jen Cotting, Khris Dodson, and Bill Whipps. EFC would like to thank the following individuals for their input and feedback: Greg Albrecht, New York Department of Agriculture and Markets; Ruth Izraeli, Chesapeake Bay Program Office; Ben Sears, New York Department of Environmental Conservation; Lauren Townley, New York Department of Environmental Conservation, and Wendy Walsh, Upper Susquehanna Coalition. Cover photos courtesy of Syracuse University Environmental Finance Center. About the Environmental Finance Center at the University of Maryland The Environmental Finance Center at the University of Maryland is part of a network of university-based centers across the country that works to advance finance solutions to environmental challenges. Our focus is protecting natural resources by strengthening the capacity of decision-makers to analyze challenges, develop effective financing methods, and build consensus to catalyze action. Through research, policy analysis, and direct technical assistance, we work to equip communities with the knowledge and tools they need to create more sustainable environments, more resilient societies, and more robust economies.