Report on the Early History of the Alexandria, Virginia Sewerage System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upper Cenozoic Deposits of the Central Delmarva Peninsula, Maryland and Delaware

Upper Ceoozoic Deposits GEOLOGICAL SXJEVilY FRQfEBSIONAL lAPEE Upper Cenozoic Deposits of the Central Delmarva Peninsula, Maryland and Delaware By JAMES P. OWENS and CHARLES S. DENNY SURFACE AND SHALLOW SUBSURFACE GEOLOGIC STUDIES IN THE EMERGED COASTAL PLAIN OF THE MIDDLE ATLANTIC STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1067-A Upper Tertiary deltaic and shallow-water marine deposits form the backbone of the peninsula. The oldest marine deposits of Pleistocene age reach a maximum altitude of 15 meters (50 feet) and have been dated radiometrically at about 100,000 years UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1979 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR CECIL D. ANDRUS, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY H. William Menard, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Owens, James Patrick, 1924- Upper Cenozoic deposits of the central Delmarva Peninsula, Maryland and Delaware. (Surface and shallow subsurface geologic studies in the emerged coastal plain of the Middle Atlantic States) (Geological Survey professional paper ; 1067-A) Bibliography: p. Includes index. Supt. of Docs, no.: I 19.16:1067-A 1. Geology, Stratigraphic Cenozoic. 2. Geology Delmarva Peninsula. I. Denny, Charles Storrow, 1911- joint author. II. Title. III. Series. IV. Series: United States. Geological Survey. Professional paper ; 1067-A. QE690.093 551.7'8 77-608325 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 Stock Number 024-001-03191-4 CONTENTS Abstract._____________________________________________________________ -

2012-AG-Environmental-Audit.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER ONE: YOUGHIOGHENY RIVER AND DEEP CREEK LAKE .................. 4 I. Background .......................................................................................................... 4 II. Active Enforcement and Pending Matters ........................................................... 9 III. The Youghiogheny River/Deep Creek Lake Audit, May 16, 2012: What the Attorney General Learned............................................................................................. 12 CHAPTER TWO: COASTAL BAYS ............................................................................. 15 I. Background ........................................................................................................ 15 II. Active Enforcement Efforts and Pending Matters ............................................. 17 III. The Coastal Bays Audit, July 12, 2012: What the Attorney General Learned .. 20 CHAPTER THREE: WYE RIVER ................................................................................. 24 I. Background ........................................................................................................ 24 II. Active Enforcement and Pending Matters ......................................................... 26 III. The Wye River Audit, October 10, 2012: What the Attorney General Learned 27 CHAPTER FOUR: POTOMAC RIVER NORTH BRANCH AND SAVAGE RIVER 31 I. Background ....................................................................................................... -

Shoreline Management in Chesapeake Bay C

Shoreline Management In Chesapeake Bay C. S. Hardaway, Jr. and R. J. Byrne Virginia Institute of Marine Science College of William and Mary 1 Cover Photo: Drummond Field, Installed 1985, James River, James City County, Virginia. This publication is available for $10.00 from: Sea Grant Communications Virginia Institute of Marine Science P. O. Box 1346 Gloucester Point, VA 23062 Special Report in Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering Number 356 Virginia Sea Grant Publication VSG-99-11 October 1999 Funding and support for this report were provided by... Virginia Institute of Marine Science Virginia Sea Grant College Program Sea Grant Contract # NA56RG0141 Virginia Coastal Resource Management Program NA470Z0287 WILLIAM& MARY Shoreline Management In Chesapeake Bay By C. Scott Hardaway, Jr. and Robert J. Byrne Virginia Institute of Marine Science College of William and Mary Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062 1999 4 Table of Contents Preface......................................................................................7 Shoreline Evolution ................................................................8 Shoreline Processes ..............................................................16 Wave Climate .......................................................................16 Shoreline Erosion .................................................................20 Reach Assessment ................................................................23 Shoreline Management Strategies ......................................24 Bulkheads and Seawalls -

Shoreline Evolution Chesapeake Bay Shoreline City of Norfolk, Virginia

Shoreline Evolution Chesapeake Bay Shoreline City of Norfolk, Virginia Virginia Institute of Marine Science College of William & Mary Gloucester Point, Virginia 2005 Shoreline Evolution Chesapeake Bay Shoreline City of Norfolk, VA C. Scott Hardaway, Jr. 1 Donna A. Milligan 1 Lyle M. Varnell 2 Christine Wilcox 1 George R. Thomas 1 Travis R. Comer 1 Shoreline Studies Program 1 Department of Physical Sciences and Wetlands Program 2 Center for Coastal Resources Management Virginia Institute of Marine Science College of William & Mary Gloucester Point, Virginia 2005 This project was funded by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality’s Coastal Resources Management Program through Grant #NA17OZ2355 of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, under the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of NOAA or any of its subagencies or DEQ. LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1. Location of the City of Norfolk within the Chesapeake Bay estuarine system...................2 Figure 2. Location of localities in the Dune Act with jurisdictional and non-jurisdictional localities noted. ...2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Figure 3. Geological map of the City of Norfolk (from Mixon et al., 1989). ...........................3 Figure 4. Index of shoreline plates.............................................................4 TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................. i Figure 5. Variability of dune and beach profiles within the City of Norfolk ............................7 Figure 6. Typical profile of a Chesapeake Bay dune system. ........................................7 LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................... i Figure 7. Photo of the Norfolk shoreline showing dune site NF3.. ...................................9 Figure 8. -

Garrett County

Appendix D- Recreation Inventory County Acres Private/ quasi-public State/Federal Acres Courts Fields Trails (Miles) Campsites Basketball Basketball Baseball Multi Swimming XC Golf Public Beach Public Boat Site Recreation Resource Recreation Resource Recreation Resource Classification Ownership Comments/Amenities Indoor Outdoor Tennis Other Gymnasium Softball Soccer Purpose Pools Skiing Hiking Biking ORV Snowmobile Total Public Pvt Courses (ft.) Launch Areas Accident Community Park East 4.1 Neighborhood Park Town of Accident Ball field, walking trail, horseshoe pits 1 1 1 0.25 0.25 Accident Community Park West 12.5 Neighborhood Park Town of Accident Pavilions, volleyball Accident Elementary School 9.6 School Recreation Park Board of Education Basketball court, playground 1 1 1 1 Accident Community Pond 2.4 Community Park Town of Accident Fishing pond Aquatic Center 1.0 Marine Private Private marina 1 ASCI -Adventure Sports Center Int'l. 17.0 Special Use Area ASCI Man-made whitewater course Avilton Community Center 2.0 Special Use Area Avilton Community Assoc. Playground, basketball court, pavilion 1 Bear Creek Hatchery Fish Mgmt. Area 113.0 Natural Resource Area State of MD Fish management area Big Run State Park 300.0 State Park State of MD Camping, fishing, Savage River Reservoir access 29 1 Bill's Outdoor Center 1.0 Marine Private Lake access, shoreline Bills Marine Service, Inc. 1.0 Marine Private Marina, boat rentals 1 Bloomington Fire Co. Town Park 3.0 Community Park Bloomington Fire Co. Basketball court, walking trail, pavilion -

The Recreation the Delmarva Peninsula by David

THE RECREATION POTENTIAL OF THE DELMARVA PENINSULA BY DAVID LEE RUBIN S.B., Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1965) SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOT THE DEGREE OF MASTER IN CITY PLANNING at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June, 1966 Signature of Author.,.-.-,.*....... .. .*.0 .. .. ...... .. ...... ... Department of City and Regional Planning May 23, 1966 Certified by.... ....... .- -*s.e- Super....... Thesis Supervisor Accepted by... ... ...tire r'*n.-..0 *10iy.- .. 0....................0 Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students 038 The Recreation Potential of the Delmarva Peninsula By David Lee Rubin Submitted to the Department of City and Regional Planning on 23 May, 1966 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning. rhis thesis is a plan for the development of Lne recreation potential of the Delmarva Peninsyla, the lower counties of Delaware and the Eastern Shore of Maryland and Virginia, to meet the needs of the Megalopolitan population. Before 1952, the Delmarva Peninsula was isolated, and no development of any kind occurred. The population was stable, with no in migration, and the attitudes were rural. The economy was sagging. Then a bridge was built across the Chesapeake Bay, and the peninsula became a recreation resource for the Baltimore and Washington areas. Ocean City and Rehoboth, the major resorts, have grown rapidly since then. In 1964, the opening of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel further accellerated growth. There are presently plans for the development of a National Seashore on Assateague Island, home of the Chincoteague ponies, as well as state parks along the Chesapeake Bay, and such facilities as a causeway through the ocean and a residential complex in the Indian River Bay. -

Arlington County Code Chapter 61

ARLINGTON COUNTY CODE ARLINGTON COUNTY CODE Chapter 61 CHESAPEAKE BAY PRESERVATION ORDINANCE* __________ * Editors Note: Ord. No. 03-1, adopted Feb. 8, 2003, amended Ch. 61, in its entirety, to read as herein set out in §§ 61-1-61-19. __________ § 61-1. Title § 61-2. Purpose and Intent § 61-3. Definitions § 61-4. Administration. § 61-5. Areas of Applicability. § 61-6. Use Regulations. § 61-7. Allowable Development, Modifications, and Encroachments in RPAs. § 61-8. Minimum Lot Size. § 61-9. Interpretation of RPA Boundaries. § 61-10. General Performance Standards for Development in Chesapeake Bay Preservation Areas. § 61-11. Reserved. § 61-12. Water Quality Impact Assessment. § 61-13. Plan of Development Process in Chesapeake Bay Preservation Areas. § 61-14. Nonconforming Uses and Structures. § 61-15. Exemptions. § 61-16. Exceptions. § 61-17. Enforcement. § 61-18. Penalties. § 61-19. Severability. § 61-1. Title This chapter shall be known and referenced as the "Chesapeake Bay Preservation Ordinance" of Arlington County. (Ord. No. 03-1, 2-8-03) § 61-2. Purpose and Intent A. This chapter is enacted to implement the requirements of § 62.1-44.15:67 et seq., of the Code of Virginia, the Chesapeake Bay Preservation Act, and the Chesapeake Bay Preservation Area Designation and Management Regulations (9VAC25-830-10 et. seq.) The intent of the County Board and the purpose of the Chesapeake Bay Preservation Area Overlay District created herein is to: 1. Protect existing high quality state waters; 2. Restore all other state waters to a condition or quality that will permit all reasonable public uses and will support the propagation and growth of all aquatic life, which might reasonably be expected to inhabit them; 3. -

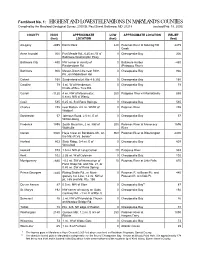

HIGHEST and LOWEST ELEVATIONS in MARYLAND's COUNTIES Compiled by the Maryland Geological Survey, 2300 St

FactSheet No. 1: HIGHEST AND LOWEST ELEVATIONS IN MARYLAND'S COUNTIES Compiled by the Maryland Geological Survey, 2300 St. Paul Street, Baltimore, MD 21218 (revised Feb. 18, 2005) COUNTY HIGH APPROXIMATE LOW APPROXIMATE LOCATION RELIEF (feet) LOCATION (feet) (feet) Allegany 2895 Dan's Rock 420 Potomac River at Sideling Hill 2475 Creek Anne Arundel 300 Fort Meade Rd., 0.25 mi. W of 0 Chesapeake Bay 300 Baltimore-Washington Pkwy Baltimore City $480 NW corner in vicinity of 0 Baltimore Harbor $480 Reisterstown Rd. (Patapsco River) Baltimore 966 Mason-Dixon Line near Stiltz, 0 Chesapeake Bay 966 Pa., on Middletown Rd. Calvert 168 Sunderland at jct Rte 4 & 262 0 Chesapeake Bay 168 Caroline 79 3 mi. W of Henderson, 0 Chesapeake Bay 79 N side of Bee Tree Rd. Carroll /1120 4 mi. NW of Manchester, 260 Patapsco River nr Marriottsville 858 0.6 mi. NW of Wentz Cecil 535 0.25 mi. S of Rock Springs 0 Chesapeake Bay 535 Charles 235 near Bolton, 4.5 mi. WNW of 0 Potomac River 235 Waldorf Dorchester 57 Johnson Road, 2.5 mi. E of 0 Chesapeake Bay 57 Williamsburg Frederick 1895 South Mountain, 2 mi. NW of 200 Potomac River at Monocacy 1695 Wolfsville River Garrett 3360 Hoye Crest on Backbone Mt., on 960 Potomac River at Bloomington 2400 the Md.-W.Va. border* Harford 803 Slate Ridge, 0.4 mi. E of 0 Chesapeake Bay 803 Whiteford Howard 873 1.5 mi. NW of Long Corner 20 Patapsco River 853 Kent 102 2.25 mi. W of Coleman 0 Chesapeake Bay 102 Montgomery /880 ~0.2 mi. -

Archaeological Survey of the Chesapeake Bay Shorelines Associated with Accomack County and Northampton County, Virginia

ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF THE ATLANTIC COAST SHORELINES ASSOCIATED WITH ACCOMACK COUNTY AND NORTHAMPTON COUNTY, VIRGINIA Survey and Planning Report Series No. 7 Virginia Department of Historic Resources 2801 Kensington Avenue Richmond, VA 23221 2003 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF THE ATLANTIC COAST SHORELINES ASSOCIATED WITH ACCOMACK COUNTY AND NORTHAMPTON COUNTY, VIRGINIA Virginia Department of Historic Resources Survey and Planning Report Series No. 7 Author: Darrin L. Lowery Chesapeake Bay Watershed Archaeological Research Foundation 5264 Blackwalnut Point Road, P.O. Box 180 Tilghman, MD 21671 2003 ii ABSTRACT This report summarizes the results of an archaeological survey conducted along the Atlantic shorelines of both Accomack County and Northampton County, Virginia. Accomack and Northampton Counties represent the southernmost extension of the Delmarva Peninsula. The study area encompasses all of the lands adjacent to the Atlantic Ocean and shorelines associated with the back barrier island bays. A shoreline survey was conducted along the Atlantic Ocean to gauge the erosion threat to the archaeological resources situated along the shoreline. Archaeological sites along shorelines are subjected to numerous natural processes which hinder site visibility and limit archaeological interpretations. Summaries of these natural processes are presented in this report. The primary goal of the project was to locate, identify, and record any archaeological sites or remains along the Atlantic seashore that are threatened by shoreline erosion. The project also served as a test of a prehistoric site predictive/settlement model that has been utilized during other archaeological surveys along the Chesapeake Bay shorelines and within the interior sections of the Delmarva Peninsula. The prehistoric site predictive/settlement model is presented in detail using archaeological examples from Maryland and Virginia’s Eastern Shore. -

5 Regions of Virginia Bordering States Major Rivers & Cities Bordering

5 Regions of Virginia Bordering States West to East All Virginia Bears Play Tag Appalachian Plateau Valley & Ridge Never Taste Ketchup Without Mustard Blue Ridge Piedmont North Carolina Tidewater/Coastal Plain Tennessee Kentucky West Virginia Maryland Major Rivers & Cities Bordering Bodies of Water North to South Alex likes Potatoes Alexandria (and DC) are on the Potomac River. Fred likes to Rap Fredericksburg is on the Rappahannock River Chesapeake Bay Yorktown is on the York River Separates mainland Atlantic King James was Rich. VA and Eastern Shore Ocean Jamestown & Richmond are on the James River. Eastern Shore Rivers Eastern Shore Peninsula Flow into the Chesapeake Bay Source of food Pathway for exploration and settlement Chesapeake Bay Provided a safe harbor Was a source of food and transportation Atlantic Ocean Provided transportation Peninsula: links between Virginia and other places (Europe, Piece of land bordered by Africa, Caribbean) water on 3 sides Fall Line Tidewater - Coastal Plain Region Low, flat land; East of the Fall Land; Includes Eastern Shore; Natural Border between Waterfalls prevent near Atlantic Ocean and Chesapeake Bay Piedmont & Tidewater further travel on Regions the rivers. Piedmont Region Relative Location The mouse is next to the box. The ball is near the box. West of the Fall Line Means "Land at the Foot of the Mountain" Blue Ridge Mountain Region Valley and Ridge Region Old, Rounded Mountains West of Blue Ridge Region Source of Many Rivers Includes the Great Valley of Virginia Piedmont to East/Valley & Ridge to West Valleys separated by ridges Part of Appalachian Mountain System Part of Appalachian Mountain System Appalachian Plateau Region Plateau Area of elevated land that is flat on top Located in Southwest Virginia Only Small Part of Plateau Located in Virginia Dismal Swamp and Valley, Ridge Definition Lake Drummond Ridge: chain of hills Located in Tidewater/Coastal Plain Region Dismal Swamp: Surveyed by George Washington; lots of wildlife Lake Drummond: Shallow lake surrounded by Valley: land between hills swamp . -

11 Section 1: Physical Setting and Segmentation

Chesapeake Bay Program Phase 6 Watershed Model – Section 11 – Physical Setting and Segmentation Final Model Documentation for the Midpoint Assessment – 10/22/2018 11 Section 1: Physical Setting and Segmentation 11.1 Physical Setting The Chesapeake Bay’s 64,000-square-mile watershed includes parts of New York, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and the entire District of Columbia (Figure 11-2). Throughout the Chesapeake Bay watershed there are more than 100,000 streams and rivers that eventually flow into the Bay (USEPA 2003a). Runoff and groundwater from the watershed flow into an estuary with a surface area of 4,500 square miles, resulting in a land-to-water surface-area ratio of 14 to 1. That high ratio is a key factor in explaining the significant influence that the watershed has on Chesapeake Bay water quality. The nine major basins of the Chesapeake Bay watershed are the Susquehanna, Potomac, Patuxent, Rappahannock, York, and James rivers and the Maryland Western Shore, Maryland Eastern Shore, and the Virginia Eastern Shore. The Chesapeake Bay Figure 11-1: States within the Chesapeake watershed is within the Bay watershed Appalachian, Ridge and Valley, Piedmont, and Atlantic Coastal Plain geologic provinces (Figure 11-1). The Atlantic Coastal Plain is a flat, lowland area with a maximum elevation of about 300 feet. The Coastal Plain extends from the edge of the continental shelf, east to a fall line that ranges from 15 to 90 miles west of the Chesapeake Bay. The fall line forms the boundary between the Piedmont Plateau and the Coastal Plain. Waterfalls and rapids clearly mark the line, which is marked by the Bay watershed cities of Baltimore, Washington, D.C., Fredericksburg, and Richmond. -

City of Alexandria, Virginia Chesapeake Bay TMDL Action Plan Phase I for 5% Compliance

City of Alexandria, Virginia Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) Action Plan for 5% Compliance June 30, 2015 For compliance with 9VAC25-890 et. seq., “General VPDES Permit for Discharges of Stormwater from Small Municipal Separate Storm Sewer Systems, Permit No. VAR040057 Prepared by: City of Alexandria, Virginia Department of Transportation and Environmental Services Infrastructure and Environmental Quality PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK Chesapeake Bay TMDL Action Plan City of Alexandria Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 1 A. MS4 Service Area ......................................................................................................................... 2 B. Existing Source Loads and Calculated Reductions ....................................................................... 2 C. Increased Loads from 2009-2014 Sources .................................................................................... 3 D. Grandfathered Projects .................................................................................................................. 4 E. Means and Methods to Meet Target Reductions ........................................................................... 4 F. Summary of Reductions ................................................................................................................ 6 G. Estimated Costs and Reductions per Strategy ..............................................................................