11 Section 1: Physical Setting and Segmentation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Upper Cenozoic Deposits of the Central Delmarva Peninsula, Maryland and Delaware

Upper Ceoozoic Deposits GEOLOGICAL SXJEVilY FRQfEBSIONAL lAPEE Upper Cenozoic Deposits of the Central Delmarva Peninsula, Maryland and Delaware By JAMES P. OWENS and CHARLES S. DENNY SURFACE AND SHALLOW SUBSURFACE GEOLOGIC STUDIES IN THE EMERGED COASTAL PLAIN OF THE MIDDLE ATLANTIC STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 1067-A Upper Tertiary deltaic and shallow-water marine deposits form the backbone of the peninsula. The oldest marine deposits of Pleistocene age reach a maximum altitude of 15 meters (50 feet) and have been dated radiometrically at about 100,000 years UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1979 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR CECIL D. ANDRUS, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY H. William Menard, Director Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Owens, James Patrick, 1924- Upper Cenozoic deposits of the central Delmarva Peninsula, Maryland and Delaware. (Surface and shallow subsurface geologic studies in the emerged coastal plain of the Middle Atlantic States) (Geological Survey professional paper ; 1067-A) Bibliography: p. Includes index. Supt. of Docs, no.: I 19.16:1067-A 1. Geology, Stratigraphic Cenozoic. 2. Geology Delmarva Peninsula. I. Denny, Charles Storrow, 1911- joint author. II. Title. III. Series. IV. Series: United States. Geological Survey. Professional paper ; 1067-A. QE690.093 551.7'8 77-608325 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 Stock Number 024-001-03191-4 CONTENTS Abstract._____________________________________________________________ -

2012-AG-Environmental-Audit.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER ONE: YOUGHIOGHENY RIVER AND DEEP CREEK LAKE .................. 4 I. Background .......................................................................................................... 4 II. Active Enforcement and Pending Matters ........................................................... 9 III. The Youghiogheny River/Deep Creek Lake Audit, May 16, 2012: What the Attorney General Learned............................................................................................. 12 CHAPTER TWO: COASTAL BAYS ............................................................................. 15 I. Background ........................................................................................................ 15 II. Active Enforcement Efforts and Pending Matters ............................................. 17 III. The Coastal Bays Audit, July 12, 2012: What the Attorney General Learned .. 20 CHAPTER THREE: WYE RIVER ................................................................................. 24 I. Background ........................................................................................................ 24 II. Active Enforcement and Pending Matters ......................................................... 26 III. The Wye River Audit, October 10, 2012: What the Attorney General Learned 27 CHAPTER FOUR: POTOMAC RIVER NORTH BRANCH AND SAVAGE RIVER 31 I. Background ....................................................................................................... -

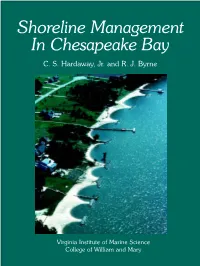

Shoreline Management in Chesapeake Bay C

Shoreline Management In Chesapeake Bay C. S. Hardaway, Jr. and R. J. Byrne Virginia Institute of Marine Science College of William and Mary 1 Cover Photo: Drummond Field, Installed 1985, James River, James City County, Virginia. This publication is available for $10.00 from: Sea Grant Communications Virginia Institute of Marine Science P. O. Box 1346 Gloucester Point, VA 23062 Special Report in Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering Number 356 Virginia Sea Grant Publication VSG-99-11 October 1999 Funding and support for this report were provided by... Virginia Institute of Marine Science Virginia Sea Grant College Program Sea Grant Contract # NA56RG0141 Virginia Coastal Resource Management Program NA470Z0287 WILLIAM& MARY Shoreline Management In Chesapeake Bay By C. Scott Hardaway, Jr. and Robert J. Byrne Virginia Institute of Marine Science College of William and Mary Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062 1999 4 Table of Contents Preface......................................................................................7 Shoreline Evolution ................................................................8 Shoreline Processes ..............................................................16 Wave Climate .......................................................................16 Shoreline Erosion .................................................................20 Reach Assessment ................................................................23 Shoreline Management Strategies ......................................24 Bulkheads and Seawalls -

Eastern Shore, VA

Community Info Sheet Eastern Shore, VA Total Population (2010): 45,553 Accomack County: 33,164 North Hampton County: 12,389 Parksley, VA: 842 (Northampton and Accomack Counties comprise the Eastern Shore of Virginia.) Things Eastern Shore is known for: Chincoteague Island & Chincoteague National Wildlife Refuge, The Chesapeake Bay, The Annual Wild Pony Round Up, NASA Wallops Flight Facility of the Eastern Shore, Tyson & Purdue Chicken Processing Plants, The Crabbing and Fishing Industry Eastern Shore Overview: The Eastern Shore of Virginia offers a historic setting, serene lifestyle, and abundant outdoor recreation. It is a 70-mile-long stretch of shoreline at the southern end of the Delmarva Peninsula. It is comprised of two counties – Accomack and North Hampton – and is bordered by the Chesapeake Bay to the West, the Atlantic Ocean to the East, and Maryland to the North. It is accessible to mainland Virginia by the 23-mile-long Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel. Prior to its completion in 1964, mainland Virginia was only accessible by ferry, or by lengthy commute through Maryland and Washington D.C. Despite being largely isolated from mainland Virginia, the Eastern Shore has a robust agricultural The Delmarva Peninsula The Eastern Shore of Virginia economy. Crabbing and fishing industries share the coastline, while large-scale produce and chicken farms utilize much of the peninsula itself. Tyson and Accomack County Census 2010 Stats* Perdue both maintain poultry processing plants on the shore and are two of the largest employers in Population: 33,164 the area. The agricultural community has drawn Race: many Hispanic or Latino immigrants and migrant 68% White workers to the area; these workers spend all or 29% African American parts of their year working in farms or factories. -

Report on the Early History of the Alexandria, Virginia Sewerage System

Report on the Early History of the Alexandria, Virginia Sewerage System Jason Tercha January 16, 2017 In 1952, the Alexandria City Council created the first sanitation authority in Virginia. Four years later, the City of Alexandria Sewer Authority opened a water-treatment facility near the mouth of Hooff’s Run. Since 1956, the water treatment facility has treated the city’s sewerage discharge, purifying the sanitary water of the city and discharging clean water back into the environment. In response to more stringent environmental standards and renewed efforts to restore the health of the Chesapeake Bay, the Alexandria Sewer Authority upgraded the facility during the late 1990s and through the 2000s. Now known as Alexandria Renew Enterprises after a 2012 rebrand, the sewerage facility remains a crucial component of the city of Alexandria’s efforts to maintain the health and prosperity of its citizens and environment. This brief overview of the city of Alexandria’s twentieth and twenty-first century efforts to manage and treat its sewerage is well documented in city records, newspapers, and the annual reports of the Alexandria Sewer Authority.1 However, as much as these recent efforts to manage waste- and stormwater are known, the city’s earlier struggles to accomplish these goals have largely remained a mystery. The obscurity of Alexandria’s early sewerage control efforts might mistakenly suggest a dearth of water management efforts in the nineteenth century. As this report demonstrates, since the city’s founding Alexandrians exerted immense efforts to manage the excess stormwater and to dispose of the human and animal wastes by incorporating new technologies and practices to respond to evolving knowledge of human health and the environment of a growing regional entrepôt. -

Scenic Landforms of Virginia

Vol. 34 August 1988 No. 3 SCENIC LANDFORMS OF VIRGINIA Harry Webb . Virginia has a wide variety of scenic landforms, such State Highway, SR - State Road, GWNF.R(T) - George as mountains, waterfalls, gorges, islands, water and Washington National Forest Road (Trail), JNFR(T) - wind gaps, caves, valleys, hills, and cliffs. These land- Jefferson National Forest Road (Trail), BRPMP - Blue forms, some with interesting names such as Hanging Ridge Parkway mile post, and SNPMP - Shenandoah Rock, Devils Backbone, Striped Rock, and Lovers Leap, National Park mile post. range in elevation from Mt. Rogers at 5729 feet to As- This listing is primarily of those landforms named on sateague and Tangier islands near sea level. Two nat- topographic maps. It is hoped that the reader will advise ural lakes occur in Virginia, Mountain Lake in Giles the Division of other noteworthy landforms in the st& County and Lake Drummond in the City of Chesapeake. that are not mentioned. For those features on private Gaps through the mountains were important routes for land always obtain the owner's permission before vis- early settlers and positions for military movements dur- iting. Some particularly interesting features are de- ing the Civil War. Today, many gaps are still important scribed in more detail below. locations of roads and highways. For this report, landforms are listed alphabetically Dismal Swamp (see Chesapeake, City of) by county or city. Features along county lines are de- The Dismal Swamp, located in southeastern Virginia, scribed in only one county with references in other ap- is about 10 to 11 miles wide and 15 miles long, and propriate counties. -

Shoreline Evolution Chesapeake Bay Shoreline City of Norfolk, Virginia

Shoreline Evolution Chesapeake Bay Shoreline City of Norfolk, Virginia Virginia Institute of Marine Science College of William & Mary Gloucester Point, Virginia 2005 Shoreline Evolution Chesapeake Bay Shoreline City of Norfolk, VA C. Scott Hardaway, Jr. 1 Donna A. Milligan 1 Lyle M. Varnell 2 Christine Wilcox 1 George R. Thomas 1 Travis R. Comer 1 Shoreline Studies Program 1 Department of Physical Sciences and Wetlands Program 2 Center for Coastal Resources Management Virginia Institute of Marine Science College of William & Mary Gloucester Point, Virginia 2005 This project was funded by the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality’s Coastal Resources Management Program through Grant #NA17OZ2355 of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Ocean and Coastal Resource Management, under the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972, as amended. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of NOAA or any of its subagencies or DEQ. LIST OF FIGURES Figure 1. Location of the City of Norfolk within the Chesapeake Bay estuarine system...................2 Figure 2. Location of localities in the Dune Act with jurisdictional and non-jurisdictional localities noted. ...2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Figure 3. Geological map of the City of Norfolk (from Mixon et al., 1989). ...........................3 Figure 4. Index of shoreline plates.............................................................4 TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................. i Figure 5. Variability of dune and beach profiles within the City of Norfolk ............................7 Figure 6. Typical profile of a Chesapeake Bay dune system. ........................................7 LIST OF FIGURES ....................................................................... i Figure 7. Photo of the Norfolk shoreline showing dune site NF3.. ...................................9 Figure 8. -

Garrett County

Appendix D- Recreation Inventory County Acres Private/ quasi-public State/Federal Acres Courts Fields Trails (Miles) Campsites Basketball Basketball Baseball Multi Swimming XC Golf Public Beach Public Boat Site Recreation Resource Recreation Resource Recreation Resource Classification Ownership Comments/Amenities Indoor Outdoor Tennis Other Gymnasium Softball Soccer Purpose Pools Skiing Hiking Biking ORV Snowmobile Total Public Pvt Courses (ft.) Launch Areas Accident Community Park East 4.1 Neighborhood Park Town of Accident Ball field, walking trail, horseshoe pits 1 1 1 0.25 0.25 Accident Community Park West 12.5 Neighborhood Park Town of Accident Pavilions, volleyball Accident Elementary School 9.6 School Recreation Park Board of Education Basketball court, playground 1 1 1 1 Accident Community Pond 2.4 Community Park Town of Accident Fishing pond Aquatic Center 1.0 Marine Private Private marina 1 ASCI -Adventure Sports Center Int'l. 17.0 Special Use Area ASCI Man-made whitewater course Avilton Community Center 2.0 Special Use Area Avilton Community Assoc. Playground, basketball court, pavilion 1 Bear Creek Hatchery Fish Mgmt. Area 113.0 Natural Resource Area State of MD Fish management area Big Run State Park 300.0 State Park State of MD Camping, fishing, Savage River Reservoir access 29 1 Bill's Outdoor Center 1.0 Marine Private Lake access, shoreline Bills Marine Service, Inc. 1.0 Marine Private Marina, boat rentals 1 Bloomington Fire Co. Town Park 3.0 Community Park Bloomington Fire Co. Basketball court, walking trail, pavilion -

The Recreation the Delmarva Peninsula by David

THE RECREATION POTENTIAL OF THE DELMARVA PENINSULA BY DAVID LEE RUBIN S.B., Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1965) SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOT THE DEGREE OF MASTER IN CITY PLANNING at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June, 1966 Signature of Author.,.-.-,.*....... .. .*.0 .. .. ...... .. ...... ... Department of City and Regional Planning May 23, 1966 Certified by.... ....... .- -*s.e- Super....... Thesis Supervisor Accepted by... ... ...tire r'*n.-..0 *10iy.- .. 0....................0 Chairman, Departmental Committee on Graduate Students 038 The Recreation Potential of the Delmarva Peninsula By David Lee Rubin Submitted to the Department of City and Regional Planning on 23 May, 1966 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in City Planning. rhis thesis is a plan for the development of Lne recreation potential of the Delmarva Peninsyla, the lower counties of Delaware and the Eastern Shore of Maryland and Virginia, to meet the needs of the Megalopolitan population. Before 1952, the Delmarva Peninsula was isolated, and no development of any kind occurred. The population was stable, with no in migration, and the attitudes were rural. The economy was sagging. Then a bridge was built across the Chesapeake Bay, and the peninsula became a recreation resource for the Baltimore and Washington areas. Ocean City and Rehoboth, the major resorts, have grown rapidly since then. In 1964, the opening of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel further accellerated growth. There are presently plans for the development of a National Seashore on Assateague Island, home of the Chincoteague ponies, as well as state parks along the Chesapeake Bay, and such facilities as a causeway through the ocean and a residential complex in the Indian River Bay. -

Salisbury/Wicomico Area Long-Range Transportation Plan

Salisbury/Wicomico Area Long-Range Transportation Plan final report prepared for Salisbury/Wicomico Area Metropolitan Planning Organization Maryland Department of Transportation October 20, 2006 Salisbury/Wicomico Area Long-Range Transportation Plan Salisbury/Wicomico Area Metropolitan Planning Organization Board Members Marvin R. Long, Wicomico County, MPO Chair Rick Pollitt, City of Fruitland, MPO Vice Chair Michael P. Dunn, City of Salisbury Charles Fisher, Tri-County Council for the Lower Eastern Shore of Maryland Luther Hitchens, Town of Delmar, Maryland Mike Nixon, Maryland Department Of Transportation John F. Outten, Town of Delmar, Delaware (Non-Voting) Stevie Prettyman, Wicomico County Ralph Reeb, Delaware Department of Transportation (Non-Voting) Theodore E. Shea II, Wicomico County Barrie P. Tilghman, City of Salisbury Technical Advisory Committee John Redden, Wicomico County Department of Public Works, Chair Ray Birch, City of Salisbury Public Works, Vice Chair Dr. Kwame Arhin, Federal Highway Administration Brad Bellaccico, City of Salisbury Chamber of Commerce, Transportation Subcommittee Bob Bryant, Ocean City/Wicomico County Airport Authority Salisbury/Wicomico Area Metropolitan Planning Organization Salisbury/Wicomico Area Long-Range Transportation Plan Bob Cook, Delmarva Water Transport Advisory Committee, (Ex-Officio) James Dooley, State Highway Administration Tracey Gordy, Maryland Department of Planning Rob Hart, Shore Transit Lenny Howard, Maryland Transit Administration Dan Johnson, Federal Highway Administration -

Water-Quality Assessment of the Delmarva Peninsula, Delaware

Water-Quality Assessment of the Delmarva Peninsula, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia-Effects of Agricultural Activities on, and Distribution of, Nitrate and Other Inorganic Constituents in the Surficial Aquifer By Pixie A. Hamilton, Judith M. Denver, Patrick J. Phillips, and Robert J. Shedlock U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Open-File Report 93-40 Towson, Maryland 1993 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director For additional information write to: Copies of this report can be purchased from: Area Assistant Regional Hydrologist, U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey, WRD Books and Open-File Reports Section 8600 LaSalle Rd, 208 Carroll Bldg. U.S. Geological Survey Denver Federal Center, Box 25425 Towson, MD21286 Denver, CO 80225 CONTENTS Abstract................................................................................................ 1 Introduction............................................................................................. 2 Purpose and scope................................................................................. 3 Acknowledgments ................................................................................ 4 Description of study area................................................................................... 4 Hydrogeology.................................................................................... 4 Description of the surficial aquifer ............................................................ 6 Occurrence and flow of ground -

Arlington County Code Chapter 61

ARLINGTON COUNTY CODE ARLINGTON COUNTY CODE Chapter 61 CHESAPEAKE BAY PRESERVATION ORDINANCE* __________ * Editors Note: Ord. No. 03-1, adopted Feb. 8, 2003, amended Ch. 61, in its entirety, to read as herein set out in §§ 61-1-61-19. __________ § 61-1. Title § 61-2. Purpose and Intent § 61-3. Definitions § 61-4. Administration. § 61-5. Areas of Applicability. § 61-6. Use Regulations. § 61-7. Allowable Development, Modifications, and Encroachments in RPAs. § 61-8. Minimum Lot Size. § 61-9. Interpretation of RPA Boundaries. § 61-10. General Performance Standards for Development in Chesapeake Bay Preservation Areas. § 61-11. Reserved. § 61-12. Water Quality Impact Assessment. § 61-13. Plan of Development Process in Chesapeake Bay Preservation Areas. § 61-14. Nonconforming Uses and Structures. § 61-15. Exemptions. § 61-16. Exceptions. § 61-17. Enforcement. § 61-18. Penalties. § 61-19. Severability. § 61-1. Title This chapter shall be known and referenced as the "Chesapeake Bay Preservation Ordinance" of Arlington County. (Ord. No. 03-1, 2-8-03) § 61-2. Purpose and Intent A. This chapter is enacted to implement the requirements of § 62.1-44.15:67 et seq., of the Code of Virginia, the Chesapeake Bay Preservation Act, and the Chesapeake Bay Preservation Area Designation and Management Regulations (9VAC25-830-10 et. seq.) The intent of the County Board and the purpose of the Chesapeake Bay Preservation Area Overlay District created herein is to: 1. Protect existing high quality state waters; 2. Restore all other state waters to a condition or quality that will permit all reasonable public uses and will support the propagation and growth of all aquatic life, which might reasonably be expected to inhabit them; 3.