UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Colianni Marty Grosz Quintet and His Hot Winds

THE TRI-STATE SKYLARK STRUTTER Member of South Jersey Cultural Alliance and Greater Philadelphia Cultural Alliance VOLUME 19 NUMBER 7 BEST OF SOUTH JERSEY 2008 MARCH 2009 ******************************************************************************************************************************** OUR NEXT CONCERTS SUNDAY, MARCH 15 SUNDAY MARCH 29 2 PM 2 PM JOHN COLIANNI MARTY GROSZ QUINTET AND HIS HOT WINDS BROOKLAWN AMERICAN LEGION HALL Dd CONCERT ADMISSION $20 ADMISSION $15 MEMBERS $10 STUDENTS $10 FIRST TIME MEMBER GUESTS Pay At the Door No Advanced Sales S SAINT MATTHEW LUTHERAN CHURCH JOHN COLIANNI 318 CHESTER AVENUE John Colianni grew up in the Washington, D.C. metro area and first heard Jazz MOORESTOWN, NJ 08057-2590 on swing-era LP re-issues (Ellington, Goodman, Jimmie Lunceford, Count Basie, Armstrong, etc.) in his parents' home. A performance by Teddy Wilson 3 BLOCKS from Main Street in Washington attended by John when he was about 12 years old also left a strong impression, as did a Duke Ellington performance (more later). 1 THE QUINTET : In 2006, looking for an outlet for his high velocity piano for Torme' from early 1991 to mid 1995, touring and recording six albums. improvisations, John formed the John Colianni Quintet. In July 2007, the group recorded its first CD, "Johnny Chops" (Patuxent Records), which was released PLAYERS FEATURED ON JOHN'S CURRENT CD this year. JUSTIN LEES: Justin, whose guitar work is characterized by a bluesy and LES PAUL: Les Paul offered the piano spot in his group to John in August infectiously swinging phrasing and a distinctive tone, is a fresh face on the jazz 2003. Les had not used a pianist in his combo since the 1950s and, in looking scene. -

Arnett Cobb the Complete Apollo Sessions Mp3, Flac, Wma

Arnett Cobb The Complete Apollo Sessions mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz / Blues Album: The Complete Apollo Sessions Country: France Released: 1984 Style: Bop, Swing MP3 version RAR size: 1855 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1437 mb WMA version RAR size: 1953 mb Rating: 4.1 Votes: 341 Other Formats: VOC AAC DXD MP1 VOX XM MPC Tracklist Hide Credits A1 Walkin' With Sid 3:02 A2 Still Flying 2:35 A3 Cobb's Idea 3:05 A4 Top Flight 2:53 When I Grow Too Old To Dream - Part I A5 3:03 Written-By – Hammerstein*, Romberg* When I Grow Too Old To Dream - Part II A6 3:03 Written-By – Hammerstein*, Romberg* Cobb's Boogie A7 2:45 Written By – LesterWritten-By – Arnett Cobb, Williams* A8 Cobb's Corner 2:40 B1 Dutch Kitchen Bounce 3:10 B2 Go, Red Go 2:37 B3 Pay It No Mind 2:57 Chick She Ain't Nowhere B4 2:57 Written-By – Arnett Cobb, Larkins* B5 Arnett Blows For 1300 2:46 B6 Running With Ray 2:50 Flower Garden Blues B7 2:57 Written By – O. ShawWritten-By – Arnett Cobb Big League Blues B8 2:33 Written-By – Arnett Cobb, Larkins* Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Apollo Records Copyright (c) – Vogue P.I.P. Distributed By – Vogue P.I.P. Made By – Disques Vogue P.I.P. Printed By – Offset France Credits Bass – Walter Buchanan Drums – George Jones Liner Notes, Photography By – André Clergeat Piano – George Rhodes Reissue Producer – André Vidal Tenor Saxophone – Arnett Cobb Trombone – Al King (tracks: A1 to A4), Michael "Booty" Wood* (tracks: A5 to B8) Trumpet – David Page* Vocals – Arnett Cobb (tracks: A5), Michael "Booty" Wood* (tracks: A5), David Page* (tracks: A5), George Jones (tracks: A5), George Rhodes (tracks: A5), Milt Larkins* (tracks: B7, B8), Walter Buchanan (tracks: A5) Written-By – Arnett Cobb (tracks: A1 to A4, A8 to B3, B5, B6) Notes ℗ 1947 Apollo Records. -

Recorded Jazz in the 20Th Century

Recorded Jazz in the 20th Century: A (Haphazard and Woefully Incomplete) Consumer Guide by Tom Hull Copyright © 2016 Tom Hull - 2 Table of Contents Introduction................................................................................................................................................1 Individuals..................................................................................................................................................2 Groups....................................................................................................................................................121 Introduction - 1 Introduction write something here Work and Release Notes write some more here Acknowledgments Some of this is already written above: Robert Christgau, Chuck Eddy, Rob Harvilla, Michael Tatum. Add a blanket thanks to all of the many publicists and musicians who sent me CDs. End with Laura Tillem, of course. Individuals - 2 Individuals Ahmed Abdul-Malik Ahmed Abdul-Malik: Jazz Sahara (1958, OJC) Originally Sam Gill, an American but with roots in Sudan, he played bass with Monk but mostly plays oud on this date. Middle-eastern rhythm and tone, topped with the irrepressible Johnny Griffin on tenor sax. An interesting piece of hybrid music. [+] John Abercrombie John Abercrombie: Animato (1989, ECM -90) Mild mannered guitar record, with Vince Mendoza writing most of the pieces and playing synthesizer, while Jon Christensen adds some percussion. [+] John Abercrombie/Jarek Smietana: Speak Easy (1999, PAO) Smietana -

Joe Henderson: a Biographical Study of His Life and Career Joel Geoffrey Harris

University of Northern Colorado Scholarship & Creative Works @ Digital UNC Dissertations Student Research 12-5-2016 Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career Joel Geoffrey Harris Follow this and additional works at: http://digscholarship.unco.edu/dissertations © 2016 JOEL GEOFFREY HARRIS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN COLORADO Greeley, Colorado The Graduate School JOE HENDERSON: A BIOGRAPHICAL STUDY OF HIS LIFE AND CAREER A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts Joel Geoffrey Harris College of Performing and Visual Arts School of Music Jazz Studies December 2016 This Dissertation by: Joel Geoffrey Harris Entitled: Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career has been approved as meeting the requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Arts in the College of Performing and Visual Arts in the School of Music, Program of Jazz Studies Accepted by the Doctoral Committee __________________________________________________ H. David Caffey, M.M., Research Advisor __________________________________________________ Jim White, M.M., Committee Member __________________________________________________ Socrates Garcia, D.A., Committee Member __________________________________________________ Stephen Luttmann, M.L.S., M.A., Faculty Representative Date of Dissertation Defense ________________________________________ Accepted by the Graduate School _______________________________________________________ Linda L. Black, Ed.D. Associate Provost and Dean Graduate School and International Admissions ABSTRACT Harris, Joel. Joe Henderson: A Biographical Study of His Life and Career. Published Doctor of Arts dissertation, University of Northern Colorado, December 2016. This study provides an overview of the life and career of Joe Henderson, who was a unique presence within the jazz musical landscape. It provides detailed biographical information, as well as discographical information and the appropriate context for Henderson’s two-hundred sixty-seven recordings. -

Prestige Label Discography

Discography of the Prestige Labels Robert S. Weinstock started the New Jazz label in 1949 in New York City. The Prestige label was started shortly afterwards. Originaly the labels were located at 446 West 50th Street, in 1950 the company was moved to 782 Eighth Avenue. Prestige made a couple more moves in New York City but by 1958 it was located at its more familiar address of 203 South Washington Avenue in Bergenfield, New Jersey. Prestige recorded jazz, folk and rhythm and blues. The New Jazz label issued jazz and was used for a few 10 inch album releases in 1954 and then again for as series of 12 inch albums starting in 1958 and continuing until 1964. The artists on New Jazz were interchangeable with those on the Prestige label and after 1964 the New Jazz label name was dropped. Early on, Weinstock used various New York City recording studios including Nola and Beltone, but he soon started using the Rudy van Gelder studio in Hackensack New Jersey almost exclusively. Rudy van Gelder moved his studio to Englewood Cliffs New Jersey in 1959, which was close to the Prestige office in Bergenfield. Producers for the label, in addition to Weinstock, were Chris Albertson, Ozzie Cadena, Esmond Edwards, Ira Gitler, Cal Lampley Bob Porter and Don Schlitten. Rudy van Gelder engineered most of the Prestige recordings of the 1950’s and 60’s. The line-up of jazz artists on Prestige was impressive, including Gene Ammons, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Eric Dolphy, Booker Ervin, Art Farmer, Red Garland, Wardell Gray, Richard “Groove” Holmes, Milt Jackson and the Modern Jazz Quartet, “Brother” Jack McDuff, Jackie McLean, Thelonious Monk, Don Patterson, Sonny Rollins, Shirley Scott, Sonny Stitt and Mal Waldron. -

Arnett Cobb Tiny Grimes Quintet Live in Paris 1974 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Arnett Cobb Tiny Grimes Quintet Live in Paris 1974 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Live in Paris 1974 Country: France Released: 1989 Style: Soul-Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1793 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1357 mb WMA version RAR size: 1635 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 891 Other Formats: VOX XM ASF AIFF MP4 MIDI MP2 Tracklist A1 Smooth Sailing 6:12 A2 El Fonko 8:20 A3 Body And Soul 5:10 B1 Jumpin' At The Woodside 8:40 B2 Just You, Just Me 9:20 B3 Willow Weep For Me 8:25 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Esoldun Phonographic Copyright (p) – INA Distributed By – Wotre Music Recorded At – Maison de Radio France Credits Bass – Roland Lobligeois Drums – Panama Francis Electric Guitar – Tiny Grimes Piano – Lloyd Glenn Tenor Saxophone – Arnett Cobb Notes Recorded April 28, 1974, Paris, Maison de la Radio. Barcode and Other Identifiers Rights Society: SACEM SDRM Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Arnett Cobb Tiny Live in Paris 1974 (CD, France's FCD 133 FCD 133 France 1989 Grimes Quintet Album) Concert Related Music albums to Live in Paris 1974 by Arnett Cobb Tiny Grimes Quintet Arnett Cobb - Wild Man From Texas Various - Atlantic Honkers - A Rhythm & Blues Saxophone Anthology Arnett Cobb - A Proper Introduction To Arnett Cobb: The Wild Man From Texas Tiny Grimes And His Rocking Highlanders - Volume Two Tiny Grimes With Roy Eldridge - One Is Never Too Old To Swing Coleman Hawkins - Hawk Eyes! Arnett Cobb, Guy Lafitte - Tenor Abrubt (The Definitive Black & Blue Sessions) Ike Quebec Quintet - Blue Harlem / Tiny's Exercise Arnett Cobb & His Orchestra - Dutch Kitchen Bounce / Go Red Go Arnett Cobb - Sizzlin' Milt Buckner / Arnett Cobb, Candy Johnson - Midnight Slows Vol.3 Arnett Cobb - The Best Of. -

Jersey Jazz Society Dedicated to the Performance, Promotion and Preservation of Jazz

Volume 43 • Issue 6 June 2015 Journal of the New Jersey Jazz Society Dedicated to the performance, promotion and preservation of jazz. Singer Tamar Korn and Jerron “Blindboy” Paxton joined Terry Waldo’s Gotham City Band on stage at The Players Club in NYC on May 3. Photo by Lynn Redmile. New York’s Hot Jazz Festival NJJS Presents Old Tunes, Young Turks A Billy Strayhorn A sold-out crowd that included such music world luminaries as George Wein and Gary Giddins and 130-plus top tier musicians Centennial Tribute filled a 19th century Gramercy Park mansion on May 3 for a June 14 | Mayo PAC, Morristown 14-hour marathon of traditional and swing era jazz at the 3rd Tickets On Sale NOW! annual New York Hot Jazz Festival. Jersey Jazz’s Lynn Redmile See Page 13 was there to take in the scene and you can read her report and see more photos beginning on page 26. New JerseyJazzSociety in this issue: New Jersey Jazz socIety Prez Sez. 2 Bulletin Board ......................2 NJJS Calendar ......................3 Jazz Trivia .........................4 Prez Sez Editor’s Pick/Deadlines/NJJS Info .......6 Crow’s Nest. 46 By Mike Katz President, NJJS Change of Address/Support NJJS/ Volunteer/Join NJJS. 47 NJJS/Pee Wee T-shirts. 48 hanks to NJJS Board member Sandy In addition, we are expecting a group from the New/Renewed Members ............48 TJosephson for contributing an outstanding jazz band of Newark Academy in Livingston to storIes guest column last month! open for the Strayhorn Orchestra, which is New York Hot Jazz Festival .......cover particularly -

![Morgenstern, Dan. [Record Review: Jean-Luc Ponty: More Than Meets the Ear] Down Beat 36:24 (November 27, 1969): 20–21](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7548/morgenstern-dan-record-review-jean-luc-ponty-more-than-meets-the-ear-down-beat-36-24-november-27-1969-20-21-3117548.webp)

Morgenstern, Dan. [Record Review: Jean-Luc Ponty: More Than Meets the Ear] Down Beat 36:24 (November 27, 1969): 20–21

Loose Wig and Lamplighter are the good hard-driving manner. The beat is standout big band sides. The former fea rock-style, and the performance has a tures a rich-toned sax section chopping certain vitality, especially in Lewis' breaks. away at a riff, answered by the unison The record opens and closes with // purr of the trombones. Cat And~rson You've Got It, although the second ver takes a few whacks in the first bndge, sion appears to be some sort of frag showing that he was a high note special mented take. It has neither beginning nor ist of the first order before joining Elling end; just a fade-in, fade-out 2: 18 of ton. Lamplighter has a small group feel heavy, driving chords. and draws much of its strength from a Enjoyable listening in the pop bag rather light, supple rhythm section and some than jazz. -McDonough superb trombone and sax voicings near the end. Mike Mainieri Overtime and Bag are more uptempo JOURNEY THRU AN lif.ECTRIC TUBE but far from the unrestrained bedlam Solid State 18049: It's All Becoming Clear Now• The Willd; Co111Jecticut Air; We' II SJ1eak Abov; which seems to have earned Hampton the the Roar; The Bush; I' II Sillg Y nu Softly of Mv indifference of some critics. Bag has Karl Life; Yes, l'111 the O11e; Allow Your Mind to W'ander. George in a straight-from-the-shoulder 16 Personnel: Jeremy Steig,. flute; Mainieri, vibra bars of trumpet. Illinois Jacquet also has harp; Warren Bernhardt, piano, organ; Joe Beck Sam Brown, guitars; Hal Gaylor, bass; Chuck 16 bars; his only solo appearance in t~e Rainey, electric bass; Donald MacDonald, drum~ LP. -

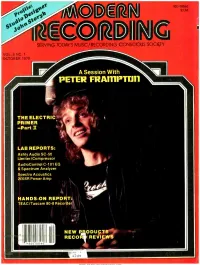

LAB REPORTS: A.Shly Audio SC -50 Limiter /Compressor Audiocontrol C -101 Ea & Spectrum Analyzer

ICD 08560 IFii $1.50 f2Dll SERVING TODAY'S MUSIC/RECORDING-CONSCIOUS SOCIETY VOL. 5 NC. 1 OCCTOB E R 1979 LAB REPORTS: A.shly Audio SC -50 Limiter /Compressor AudioControl C -101 Ea & Spectrum Analyzer r o i 111 4 20 08560 www.americanradiohistory.com THE LONG AND THE SHORT OF SOUND REINFORCEMENT. You know about the equalizer, echo and from a compact source dance monitor output long part. Separate reverb control all in one that is easy to set up levels ( +4dB into 10K components can keep unit -great flexibility and operate. ohms, and 0dB into 600 your hands full, what with options to expand The EM -200 has ohms). Additionally, with the extra help and and enlarge. eight input channels eight patch points allow time needed to get your The EM -200 and and 120 -watt speaker you to connect acces- sound reinforcement EM -300 are ideal for output. The EM -300 has sories directly to the act together. small to medium size 12 input channels and mixer's power amp for Now for the short reinforcement applica- 200 -watt speaker out- dramatically lower part. The Yamaha tions, wherever you put. For increased noise levels. EM -200 and EM -300 need a precisely flexibility, both the The EM -200 and stereo output integrated placed, superbly clean EM -200 and EM -300 EM -300 give you the mixers. They leave and well- defined sound have hi and lo impe- short-cut to reinforce- you free to concentrate ment that won't short- on the creativity change the quality of of your job, not your sound. -

"The Texas Shuffle": Lone Star Underpinnings of the Kansas City

Bailey: The Texas Shuffle Produced by The Berkeley Electronic Press, 2006 1 'k8 Texas Shume ': Lone Star Underpinnings of the Kansas Civ Jcm Sound Journal of Texas Music History, Vol. 6 [2006], Iss. 1, Art. 3 7he story of Amerlcan juz is often .d~minakdby discussions of New Weans and of juz music's migro- 1 Won up the Mississippi RRlver into the urban centers of New York, Chicago, 1 Philadelphia, Detroit, and St. Louis. I mis narrative, whlle accurate in mony respecis, belies the true I nature of the music and, as with b any broad hisforIca1 generaliizu- tion, contulns an ultimate presump tlve flaw The emergence of jan cannot be aftributed solely fo any single clfy or reglon of he country. Instead, jan music Grew out of he collective experiences of Amerl- k b- .r~& cans from VU~~Wof backgrounds , living ihroughout the ndon.1 The routinely owrlookd conmibutions of T- &m to the dcvclopment of jazz unhmthe ndfor a broader un- of how chis music drew from a wide range of regidinfluenm. As dyas the I920s, mwhg pups of jm musidans, or %tory bands,* whicb indudad a n& of Tarnns, were hdping spread dmughout &t Souktand Miwest in such wwns as Kana City, Daltas. Fort Wod, Mo,Hnumn, Galveston. Sm Antonio, Tulsa, Oklahoma City, and beyond. The w11cctive iducnaof dmc musihbought many things to /bear on the dmeIopment of American jazz, including a cemh smsc of frcwlom md impraviaation dm later would be rcseewd in the erne- of bebop ad in the impromp jam dm,or eonmrs," rhac mn until dawn and helped spdighr youagu arrists and Md, new musical hmuiom.' The Tmas and sourhwesrern jas~ http://ecommons.txstate.edu/jtmh/vol6/iss1/3 2 Bailey: The Texas Shuffle scenes, while not heralded on the same scale as those in New in competitive jam sessions, or cutting contests, which allowed Orleans, Chicago, and New York City, have not gone artists to hone their skills, display their talents, and establish completely unnoticed by scholars. -

Airwaves (1983-02 And

·AIRWAVES A Service of Continuing Education and Extension tm · University of Minnesota, Qulut~ ·- - . February-March 1983 .... C 0 -a (1) 0 :::c -a C C ..c-.... -0 ...z '"I- ....0 \ Cl) / 0 ..c C Cl) Cl) (I) Ii.. C ' '.'> "<C ·~. \ ..c "' 1 f 0 \ - - ..._ I I\UM() \taff S1a1ion Managtt , ...... Tum Livingsion Program Dittc;tor ... •. ... • John Zi~glrr -,\nt. Program Dirl'<'1or . .• •. Paul Schmitz t:nginttring .. .. .. ... ..... Kirk Kintm Producn/Ou1ttach ....... Jran Johnson AIRWAVES is the bi-monthly program Re or>t to the Listener guide of KUMD, which is the 100,000 watt public radio station at the University of Minnesota-Duluth, broadcasting at 103.3 fro. KUMD is part By Tom Livingston, Station Manager of University Media Resources, a department of Continuing Education The next several weeks will see the NPR PLAYHOUSE - A 5 days/week ½ help. If you just can't wait, go to the and Extension at the University of worst of winter over and the first glimmer- hour radio drama program. With Twin Cities and visit some of the big Minnesota . KUMD's program ings of spring (How's that for optimistic?). the demise of "CBS Mystery record stores there. If that isn't pos- · philosophy is to provide the highest It will also bring another several weeks Theater", I think it will be the sible I suggest you write the record quality non-commercial program- of some of the finest radio anywhere only daily radio drama program company and ask if they will send you ming, including music, news and from KUMD (a lead-pipe cinch). -

Main Artist (Group) Album Title Other Artists Date Cannonball Adderley

Julian Andrews Collection (LPs) at the Pendlebury Library of Music, Cambridge list compiled by Rachel Ambrose Evans, August 2010 Main Artist (Group) Album Title Other Artists Date Cannonball Adderley Coast to Coast Adderley Quintet 1959/62 and Sextet (Nat Adderley, Bobby Timmons, Sam Jones, Louis Hayes, Yusef Lateef, Joe Zawinul) Cannonball Adderley The Cannonball Wes Montgomery, 1960 Adderley Victor Feldman, Collection: Ray Brown, Louis Volume 4 Hayes Nat Adderley Work Songs Wes Montgomery, 1978 Cannonball Adderley, Yusef Lateef Larry Adler Extracts from the film 'Genevieve' Monty Alexander Monty Strikes Ernest Ranglin, 1974 Again. (Live in Eberhard Weber, Germany) Kenny Clare Monty Alexander, Ray Brown, Herb Triple Treat 1982 Ellis The Monty Alexander Quintet Ivory and Steel Monty Alexander, 1980 Othello Molineux, Robert Thomas Jr., Frank Gant, Gerald Wiggins Monty Alexander Ivory and Steel (2) Othello Molineux, 1988 Len Sharpe, Marshall Wood, Bernard Montgomery, Robert Thomas Jr., Marvin Smith Henry Allen Henry “Red” 1929 Allen and his New York Orchestra. Volume 1 (1929) Henry Allen The College Steve Kuhn, 1967 Concert of Pee Charlie Haden, Wee Russell and Marty Morell, Henry Red Allen Whitney Balliett Mose Allison Local Color Mose Allison Trio 1957 (Addison Farmer, Nick Stabulas) Mose Allison The Prestige Various 1957-9 Collection: Greatest Hits Mose Allison Mose Allison Addison Farmer, 1963 Sings Frank Isola, Ronnie Free, Nick Stabulas Mose Allison Middle Class Joe Farrell, Phil 1982 White Boy Upchurch, Putter Smith, John Dentz, Ron Powell Mose Allison Lessons in Living Jack Bruce, Billy 1982 Cobham, Lou Donaldson, Eric Gale Mose Allison Ever Since the Denis Irwin, Tom 1987 World Ended Whaley Laurindo Almeida Laurindo Almeida Bud Shank, Harry quartet featuring Babasin, Roy Bud Shank Harte Bert Ambrose Ambrose and his Various 1983 Orchestra: Swing is in the air Albert Ammons, Pete Johnson Boogie Woogie 1939 Classics Albert Ammons, Pete Johnson, Jimmy Boogie Woogie James F.