Data Collection of Japanese Dialects and Its Influence Into Speech Recognition Ikuo KUDO, Takao NAKAMA, Tomoko WATANABE and Reiko KAMEYAMA

Total Page:16

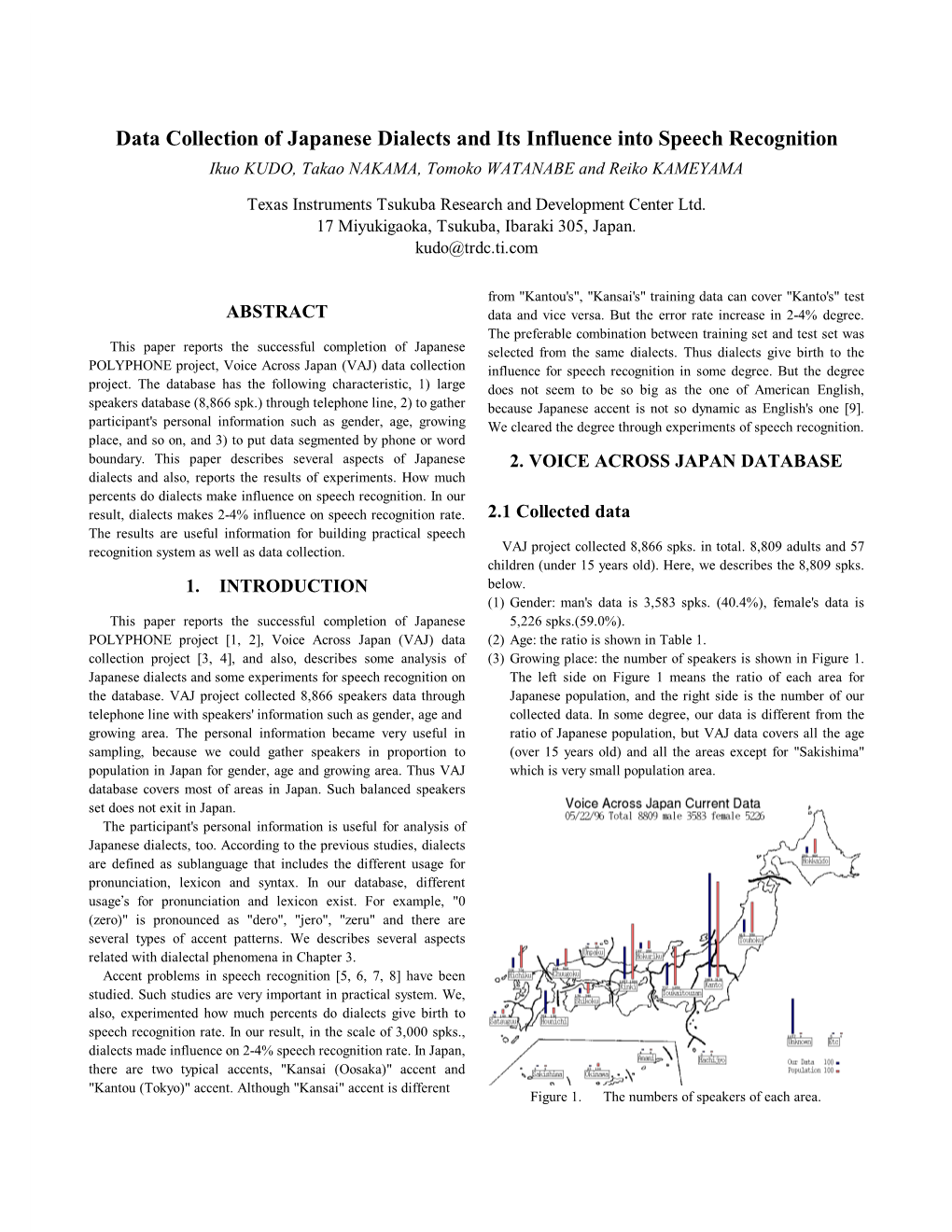

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research on Endangered Ryukuan Dialects with an Aim to Preserve

KAKENHI NEWS2009 vol.2 Research on Endangered Ryukuan Dialects � Culture & � Society with an Aim to Preserve and Propagate Shigehisa Karimata� Professor� University of the Ryukyus 【Background】� /ã, õ, ı˜/and /ë˜/ for a total of 18 vowels. particle ga is spoken in the interrogative, UNESCO announced in February 2009 But the dialect of Yonakuni Island, the and nu in yes-or-no questions, to enable that of the over six thousand languages westernmost island in Japan, primarily the speaker to add extra meaning to his spoken in the world, 2500 are in danger use the three vowels a, i and u. The Miya- question. The Ryukyuan languages shed of becoming extinct. Among them are Ja- ko Ookami Island dialect has only 10 con- light on the history of the Japanese lan- pan's Ryukyuan languages (UNESCO sonants: /p, t, k, f, v, s, m, n, j/and /r/. But guage, and has many interesting linguistic treats each Ryukyuan dialect as a separate it has been discovered that the consonants typological features. � language). Although experts have long /f, v, s, m/ and n are used as monosylla- � been aware of the threat to the dialects, bles, that the /f/ and /s/ in words such as 【Outlook】� and research on their preservation and /kffi/ (make) and /pstu/ (person) function Urgent research is needed on the Ryu- propagation has been ongoing for more as vowels in a syllable, and that there are kyuan languages in order to pass them than 30 years, the inclusion of Ryukyu also long and short consonants, with down to future generations. -

'Accentless' and Standard Japanese Dialects

ICPhS XVII Regular Session Hong Kong, 17-21 August 2011 SUBTLE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THE SPEECH OF YOUNG SPEAKERS OF ‘ACCENTLESS’ AND STANDARD JAPANESE DIALECTS: AN ANALYSIS OF PITCH PEAK ALIGNMENT Akira Utsugia,b, Masatoshi Koizumic & Reiko Mazukaa,d aRIKEN Brain Science Institute, Japan; bJSPS; cTohoku University, Japan; dDuke University, USA [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] ABSTRACT ame (HL) ‘rain’ vs. ame (LH) ‘candy’, are non- existent; those words are distinguished only by Japanese dialects are largely classified into two context. types in terms of prosodic systems, one having a Previous studies have reported that younger lexical pitch contrast and the other having no such speakers in areas known as accentless dialects had contrast. Dialects of the latter type are called acquired the Standard Japanese tonal system and ‘accentless’ dialects. Many previous studies are thus no longer ‘accentless’ [11, 14, 16]. For reported that, in areas where an accentless dialect example, Onishi reported that “speakers of the had been originally spoken, younger speakers Sendai dialect, which was originally ‘accentless’, acquired Standard Japanese lexical pitch accent have acquired lexical pitch accent. This process and are thus no longer accentless. We replicated has completed in younger generation” [14]. this finding when we followed the traditional However, the subtle differences between the approach of categorically labeling recorded tokens. standard and accentless dialects may not be However, an acoustic analysis -

Ryukyu Language (The Shuri Dialect)

International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education (IJHSSE) Volume 2, Issue 11, November 2015, PP 115-123 ISSN 2349-0373 (Print) & ISSN 2349-0381 (Online) www.arcjournals.org Examining the Grammatical Functions of the Auxiliary Verb Rijun in the Shuri Dialect of Ryukyuan Languages Yan Kit Kwong Department of Asian and International Studies, City University of Hong Kong Y7714, Department of Asian and International Studies, Yellow Zone, 7/F, Academic 1, City University of Hong Kong, Tat Chee Avenue, Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong [email protected] Abstract: This paper reexamines the functions of the auxiliary verb rijun (or riin) in the Ryukyuan languages. Ryukyuan languages, which are widely considered as sister languages to Japanese language, can be divided into Northern Ryukyuan languages and Southern Ryukyuan languages. This paper focuses on the Shuri dialect, one of the dialects belonging to the Northern Ryukyuan languages. In Ryukyuan languages, the auxiliary verb rijun can be used to express passive, potential, and honorific morpheme. In this paper, the author aims to reexamine the functions of rijun in order to clarify the grammatical functions and characteristics of rijun. Keywords: Ryukyuan language, Shuri dialect, auxiliary verb, rijun, passive voice, honorifics, potential form. 1. INTRODUCTION Ryukyuan languages are widely considered as sister languages of the Japanese language [1]. Phonological and grammatical similarities are found between Ryukyuan languages and Japanese Kyushu dialects and they also show close lexical connections [2]. Ryukyuan languages can be divided into two main groups, namely Northern Ryukyu language and Southern Ryukyu language. Northern Ryukyu language is further divided into Northern Amami dialect, Southern Amami and Northern Okinawa dialect, and South Central Okinawa dialect; on the other hand, Southern Ryukyu language can be subdivided into Miyako dialect, Yaeyama dialect, and Yonaguni dialect [3]. -

Introduction to Japanese Computational Linguistics Francis Bond and Timothy Baldwin

1 Introduction to Japanese Computational Linguistics Francis Bond and Timothy Baldwin The purpose of this chapter is to provide a brief introduction to the Japanese language, and natural language processing (NLP) research on Japanese. For a more complete but accessible description of the Japanese language, we refer the reader to Shibatani (1990), Backhouse (1993), Tsujimura (2006), Yamaguchi (2007), and Iwasaki (2013). 1 A Basic Introduction to the Japanese Language Japanese is the official language of Japan, and belongs to the Japanese language family (Gordon, Jr., 2005).1 The first-language speaker pop- ulation of Japanese is around 120 million, based almost exclusively in Japan. The official version of Japanese, e.g. used in official settings andby the media, is called hyōjuNgo “standard language”, but Japanese also has a large number of distinctive regional dialects. Other than lexical distinctions, common features distinguishing Japanese dialects are case markers, discourse connectives and verb endings (Kokuritsu Kokugo Kenkyujyo, 1989–2006). 1There are a number of other languages in the Japanese language family of Ryukyuan type, spoken in the islands of Okinawa. Other languages native to Japan are Ainu (an isolated language spoken in northern Japan, and now almost extinct: Shibatani (1990)) and Japanese Sign Language. Readings in Japanese Natural Language Processing. Francis Bond, Timothy Baldwin, Kentaro Inui, Shun Ishizaki, Hiroshi Nakagawa and Akira Shimazu (eds.). Copyright © 2016, CSLI Publications. 1 Preview 2 / Francis Bond and Timothy Baldwin 2 The Sound System Japanese has a relatively simple sound system, made up of 5 vowel phonemes (/a/,2 /i/, /u/, /e/ and /o/), 9 unvoiced consonant phonemes (/k/, /s/,3 /t/,4 /n/, /h/,5 /m/, /j/, /ó/ and /w/), 4 voiced conso- nants (/g/, /z/,6 /d/ 7 and /b/), and one semi-voiced consonant (/p/). -

How to Translate Dialects: a Segmentation-Centric Pivot Translation Approach

Information and Media Technologies 8(4): 1166-1186 (2013) reprinted from: Journal of Natural Language Processing 20(4): 563-583 (2013) © The Association for Natural Language Processing How to Translate Dialects: A Segmentation-Centric Pivot Translation Approach Michael Paul†, Andrew Finch† and Eiichiro Sumita† Recent research on multilingual statistical machine translation (SMT) focuses on the usage of pivot languages in order to overcome resource limitations for certain lan- guage pairs. This paper proposes a new method to translate a dialect language into a foreign language by integrating transliteration approaches based on Bayesian align- ment (BA) models with pivot-based SMT approaches. The advantages of the pro- posed method with respect to standard SMT approaches are threefold: (1) it uses a standard language as the pivot language and acquires knowledge about the relation between dialects and a standard language automatically, (2) it avoids segmentation mismatches between the input and the translation model by mapping the character sequences of the dialect language to the word segmentation of the standard language, and (3) it reduces the translation task complexity by using monotone decoding tech- niques. Experiment results translating five Japanese dialects (Kumamoto, Kyoto, Nagoya, Okinawa, Osaka) into four Indo-European languages (English, German, Rus- sian, Hindi) and two Asian languages (Chinese, Korean) revealed that the proposed method improves the translation quality of dialect translation tasks and outperforms standard pivot translation approaches concatenating SMT engines for the majority of the investigated language pairs. Key Words: Dialect Languages, Pivot Translation, Word Segmentation 1 Introduction The translation quality of SMT approaches heavily depends on the amount and coverage of the bilingual language resources available to train the statistical models. -

Origins of the Verbalizer Affixes in the Japonic Languages

ORIGINS OF THE VERBALIZER AFFIXES IN THE JAPONIC LANGUAGES Tyler Lau Advisors: Claire Bowern and Stephen R. Anderson May 1st, 2012 ABSTRACT The affix that verbalizes adjectives in the Japonic languages is traditionally viewed as deriving from one of two constructions: *ku a(r)-, an adverbializer + existential verb, or *-sa a(r)-, a nominalizer + existential verb (Martin 1987, Bentley 2001, Chamberlain 1895, etc.). However, Izuyama (1997) argues that this view is taken at face value and ignores phonological correspondences with the southern Japonic languages, notably Yaeyama and Yonaguni. She argues instead that the form originates in the completive forms of three or four reconstructed verbs *s(u), *k(u), *i(r ∼s), all meaning ‘to do’. In my work, I gathered comparative morphological and phonological evidence from wordlists, grammars and my own fieldwork with a speaker of Okinawan, to test these hypotheses. However, my findings also lead me to reject Izuyamas reconstruction of *i(r~s) as a valid reconstruction of ‘to do’ or as relevant to the verbalizer affix. Rather, I establish its origins in a Proto-Ryukyuan verb *er- ‘to get,’ descending from Proto-Japanese *e- that grammaticalized to attach to consonant-stem verbs, to create an inchoative or valency-changed class of vowel-stem verbs. I also tentatively reconstruct the verb ‘to do’ as *as-, a transitive form of the verb *ar- ‘to exist.’ In agreement with Izuyama, however, I found that there is ample evidence supporting the hypothesis that the verbalizer affix originates in the completive and/or past form of verbs meaning ‘to do’ and provide both comparative and theoretical evidence for this claim. -

Japanese Learners of English and Japanese Phonology

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE RESEARCH BULLETIN OF NARUTO UNIVERSITY OF EDUCATION Volume342019 Japanese Learners of English and Japanese Phonology KITA Yoko (Keywords: English language education, Japanese Learners of English, Japanese Phonology) 1. Introduction Globalization has brought a drastic change to English Education since English is now considered an International language in Japan. According to a survey given out in Japan by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology in 2017, most of the junior high schools nationwide conduct English lessons as a prioritized foreign language. Compulsory English Education in Japan starts the fifth year of elementary school at the age of ten and continues until the third year of junior high school. If a student attends high school and university, which is voluntary after the age of sixteen, then the student must take another three to seven years of English. Since all Japanese must go through a large amount of English education during school, there needs to be a focus on creating a learning environment that helps them become proficient in English. This paper will discuss how Japanese learners of English are influenced by their native language of Japanese, when producing English sounds and it will provide teaching methods to correct pronunciation errors. 2. Japanese Language Japanese is the official language of Japan. However, including Japanese emigrant countries, more than 120 million people speak Japanese throughout the world. The lingua franca of Japan is called Standard Language or Kyotsugo, which is principally based in the Tokyo area. -

Uhm Phd 4271 R.Pdf

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I LIBRARY A RECONSTRUCTION OF THE ACCENTUAL HISTORY OF THE JAPANESE AND RYUKYUAN LANGUAGES A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN LINGUISTICS DECEMBER 2002 BY Moriyo Shimabukuro Dissertation Committee: Leon A. Serafim, Chairman Robert Blust Kenneth Rehg Patricia Donegan Robert Huey llJ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Looking back upon my life in Honolulu, I have realized how wonderful my life has been. Vivid memories come back as if I am turning pages of a picture album. People that I have met made my life here precious. My studies at the University of Hawai'i at Manoa have been very fruitful. Since the day I arrived, I have learned a great number of things about the Japonic languages from Leon A. Serafim, my advisor. I have really enjoyed myself being with him. This dissertation could not have been completed without his valuable comments, insightful suggestions, and encouragement. lowe him a great amount, especially his time and energy that he spent with me while I was writing my dissertation. To express my appreciation, I would like to say "Ippee nihwee deebiru." I would also like to thank my other committee members, Ken Rehg, Robert Blust, Patricia Donegan, and Robert Huey, for reading this dissertation and giving me insightful comments. I learned a lot from discussions with them. I am grateful to them for being on my committee. I would also like to express my gratitude to Alexander Vovin, who has taught me a lot in class and outside classrooms while I was at the university. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. THE EARLY FICTION OF MATSUMOTO SEICHO: DETECTIVE FICTION AS SOCIAL CRITIQUE DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the The Ohio State University By Michael S. Tangeman, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2002 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Dr. William J. Tyler, Adviser Dr. Richard Torrance JcMl Dr. Mark Bender / Adviser department of East/Asian Languages and Literatures Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Regional Variation on Loanword Adaptation in Japanese

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2020 Regional Variation on Loanword Adaptation in Japanese Yuki Hattori [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the Modern Languages Commons, and the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Hattori, Yuki, "Regional Variation on Loanword Adaptation in Japanese" (2020). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 7583. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/7583 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Regional Variation on Loanword Adaptation in Japanese Yuki Hattori Thesis submitted To the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in World Languages, Literatures, and Linguistics (Linguistics) Department -

Prosodic Structures of Different Japanese Dialects and the Universality of the Syllable

Prosodic structures of different Japanese dialects and the universality of the syllable Wan-Lung David LI Student number 10620133 Supervisor: Silke Hamann Thesis submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (MA) in the Programme Master of Arts in General Linguistics Graduate School of Humanities © David Li 2014 University of Amsterdam 2014 Acknowledgments I would like to express my gratitude and appreciation for some persons who have helped me during the process of writing this thesis. First of all, much of the gratitude goes to my supervisor Silke Hamann, who has guided and helped me a lot in my study throughout my master programme. Without her valuable comments the completion of this thesis would not have been possible. Thank you a lot for giving me many opinions not only about this thesis, but also about my study and my future. I also want to thank Jeroen Breteler for giving me many important insights in the formalizations. The discussion I have had with you was really helpful. Besides those helping me during the writing of this thesis, I would like to express my gratitude to all other teachers who have taught me in this year. It has been difficult for me to pursue in linguistics since I did not get my bachelor degree in linguistics, so I really appreciate all study opportunities I have got in this programme. My special gratitude goes to Kees Hengeveld and Enoch Aboh, who allowed me to sit in the course Perspective of Universals I and taught me a lot, although I was not registered for the course. -

Accounts of an Eikaiwa Sensei. Sociolinguistics of Japanese and the Impact of EFL on Its Society

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 471 313 FL 027 511 AUTHOR Drakos, Joe TITLE Accounts of an Eikaiwa Sensei. Sociolinguistics of Japanese and the Impact of EFL on Its Society. PUB DATE 2001-08-10 NOTE 23p. PUB TYPE. Reports - Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01!PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Elementary Secondary Education; *English (Second Language); Foreign Countries; Higher Education; *Linguistic Borrowing; Regional Dialects; Second Language Learning; *Socio1inguistics; Writing (Composition) IDENTIFIERS *Japan; *Language Contact ABSTRACT This paper explains that change is part of every language, noting that it occurs from both internal manipulation (e.g., youth culture) and external influences (contact with other languages). The paper focuses on external influences as they apply to Japanese and discusses how much external influence, specifically English, is too much. Today, Japan utilizes more than 30,000 English words, many of which have been "Japanized." This migration to English has led to the abandonment of the original Japanese translations, and the characters that accompany them have given way to "Katakana," the Japanese syllabic set for foreign words. This paper examines the impact of English on Japanese, noting the linguistic and social aspects of Japanese. Information comes from observations, interviews, and experiences as a teacher of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) to Japanese students of varying ages. It discusses the following: the linguistics of Japanese; writing systems; variants of speech; dialects of Japanese; sociolinguistics of Japanese; the impact of English on Japan; and how to teach EFL to Japanese people. The paper examines 5 years of fieldwork, offering four case studies of different types of students in different teaching contexts.