Content-Based Regulation of Electronic Media: Indecent Speech on the Internet, 21 J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Design, Construction and Testing of a Low Energy Digital Frequency Modulation (FM) Transmitter

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research Volume 11, Issue 1, January-2020 534 ISSN 2229-5518 Design, Construction and Testing of a Low Energy Digital Frequency Modulation (FM) Transmitter JP. C. Mbagwu, F.M.Ezike, J.O.Ozuomba Abstract---- A rapidly growing demand for the use of Frequency Modulation (FM) transmitter exists within institutions and individuals. The FM transmitters are however a complex equipment demanding high power supply, high voltage system design, critical maintenance and exorbitant price. These problems of the transmitter constitute major impediments to institutions and individuals that may wish to adopt radio broadcast as means of electronic media. This study was therefore carried out to design and construct an FM transmitter that is of low cost, and simple in maintenance, efficient in use and yet operating on low power supply. The FM transmitter is designed to be received at a range of about 100metres in free air. The transmitter has a capacitor microphone which picks up very weak sound signals, a transistor, resistors, inductor, and capacitors. The design procedure involves the modification of an output of the transmitter. Based on the procedures adopted and the tests carried out, the specific findings include a range of 102.2MHz of transmission from a 9V DC battery. The work indicated that the practical frequency modulated (FM) transmitter requiring a low power can be designed and constructed. Index Terms----Frequency Modulation, FM Transmitter, Radio Broadcast, Antenna. 1.0 INTRODUCTION combined in one unit are called a transceiver. The In electronics and telecommunication, a transmitter term transmitter is often abbreviated ‘‘XMTR’’ or or radio transmitter is an electronic device which ‘‘TX’’ in technical documents. -

Electrical Engineering (ELEC ENG) 1

Electrical Engineering (ELEC_ENG) 1 Prerequisite: ELEC_ENG 302-0 or equivalent. ELECTRICAL ENGINEERING ELEC_ENG 334-0 Fundamentals of Blockchains and Decentralization (1 Unit) (ELEC_ENG) This course is partly an introduction to the fundamentals of blockchains and decentralized applications and partly a springboard toward ELEC_ENG 302-0 Probabilistic Systems (1 Unit) deeper understanding and further exploration. The course explains Introduction to probability theory and its applications. Axioms of how blockchains work; teaches the underlying fundamentals of probability, distributions, discrete and continuous random variables, distributed consensus; provides hands-on experience through computer conditional and joint distributions, correlation, limit laws, connection assignments; and also touches upon economic and policy issues. to statistics, and applications in engineering systems. May not receive Prerequisites: COMP_SCI 212-0 or ELEC_ENG 302-0 or equivalent or credit for both ELEC_ENG 302-0 and any of the following: IEMS 202-0; graduate standing and basic programming skills. MATH 310-1; STAT 320-1; ELEC_ENG 383-0, ELEC_ENG 385-0. Corequisite: MATH 228-2 or equivalent. ELEC_ENG 353-0 Digital Microelectronics (1 Unit) Logic families, comparators, A/D and D/A converters, combinational ELEC_ENG 307-0 Communications Systems (1 Unit) systems, sequential systems, solid-state memory, largescale integrated Analysis of analog and digital communications systems, including circuits, and design of electronic systems. modulation, transmission, and demodulation of AM, FM, and TV systems. Prerequisites: COMP_ENG 203-0, ELEC_ENG 225-0. Design issues, channel distortion and loss, bandwidth limitations, additive noise. ELEC_ENG 359-0 Digital Signal Processing (1 Unit) Prerequisites: ELEC_ENG 222-0, ELEC_ENG 302-0 or equivalent. Discrete-time signals and systems. -

The Influence of the Mass Media in the Behavior Students: a Literature Study

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 2017, Vol. 7, No. 8 ISSN: 2222-6990 The Influence of the Mass Media in the Behavior Students: A Literature Study Noradilah Abdul Wahab1, Mohd Shahril Othman2, Najmi Muhammad3 1 Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin (UniSZA), Kampus Gong Badak. Kuala Terengganu 2 Lecturer, Faculty of Islamic Contemporary Studies, Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin (UniSZA) 3 Universiti Malaysia Perlis (UniMAP), Arau, Perlis. DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i8/3218 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v7-i8/3218 Abstract The highly developed and complex of technology has grown up along the current style of the world which had introduces the human to a wide range of communication tools, as well as communications today. Mass media is a means of conveying information simultaneously and accessible to the community all over the world. In present era of globalization, the modernization make it easier for people to carry out their daily lives. However, this sophistication has both positive and negative to the user. The mistake in using this facility will become a threat that can contribute the social problems in society. The objective of this writing is to see the influence of mass media in the formation of student personality. The method of writing is qualitative based on previous studies and research through documents, journals and books related to the discussion of the influence of mass media. The method of literature is the primary basis in this writing that inductively and deductively analyzes by studying literature from both local and western researchers until a strong conclusion in identifying mass media influences on student behavior can be achieved. -

Rtv 3001 Introduction to Telecommunication Section 4324

RTV 3001 INTRODUCTION TO TELECOMMUNICATION SECTION 4324 IMPORTANT INFORMATION: Instructor: William A. Renkus, Ph. D. Lecture: Tuesday, Period 10 (5:10 pm – 6:00 pm) & Thursday, Periods 10 - 11 (5:10 pm 7:05 pm)) Room: TUR L007 Office: 3065 Weimer (subject to change) Office Hours: Wednesday & Friday 1:45 PM – 2:45 PM & by appointment E-mail: [email protected] E-Learning: http://lss.at.ufl.edu/ COURSE DESCRIPTION: Electronic media encompass all contemporary paths of mass communication into our lives: radio, television, cable, satellite and the Internet. This course investigates their dynamic influence by unveiling principles that govern media channels of information and entertainment. The goal for students is to understand how our media tools were created, were nurtured into an information industry, and now shape our lives in political, economic, and social ways. We will critically analyze the latest developments from the standpoints of media owners, advertisers, managers, producers, and audiences. COURSE OBJECTIVES: Students will gain knowledge of the telecommunication industry with an emphasis on learning specifically about broadcasting and cable. In addition, changes in new media, business practices, converging markets, and regulatory philosophies will be addressed. This course is designed to offer you an overview of the origins, organizations, and movements that have shaped electronic media. We will learn and discuss the following developments: The historical development of electronic media The technologies involved in the creation of electronic media The structure, economics, and regulation of electronic media The political and legal issues involved in content and management decisions The economics of electronic media, including programming and ratings The lexicon involved within subsets of the telecommunication industry REQUIRED TEXTBOOK: Joseph R. -

Broad&Elec Media.Vp

REQUIREMENTS FOR THE BACHELOR OF ARTS IN JOURNALISM GAYLORD COLLEGE OF JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATION THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA Minimum Credit Hours and Grade Averages Required For Students Entering the Credit Hours: Journalism & Mass Oklahoma State System Total - 130 Upper-Division Within Total - 48 Communication— for Higher Education: Major - 33 Upper-Division Within Major -27 Broadcasting & Electronic Summer 2002 Grade Point Averages: Media— 0603G through Overall: Combined OU/Transfer - 2.25 OU - 2.00 Last 60 Hours - 2.25 Bachelor of Arts Spring 2003 Major: Combined OU/Transfer - 2.25 OU - 2.00 in Journalism GENERAL EDUCATION AND COLLEGE REQUIREMENTS MAJOR REQUIREMENTS Hours MAJOR REQUIREMENTS - Hours Courses graded S/U or P/NP will not apply. continued Courses for fulfillment of General Education and College of Journalism requirements JOURNALISM & MASS COMMUNICATION Requirements for admission to the Gaylord College must be from the approved General Education course list. of Journalism and Mass Communication are University-Wide General Education Requirements 1013 Intro. to Mass Communication 3 outlined on the back of this page. (minimum 40 hours) 2033 Writing for Mass Media 3 A maximum of 40 hours of Journalism and Mass Core Area I: Symbolic and Oral Communication (9-19 hours, 3-5 courses) Communication may be counted in the 130 hours a: English Composition (6 hours, 2 courses) 3622 Writing for Broadcast 2 required for graduation. No student will be awarded 1. English 1113, Principles of English Composition a BA in Journalism degree without completing at 2. English 1213, Principles of English Composition 3632 Audio Production 2 least 90 semester credit hours outside the College. -

The Big Picture: HDTV and High-Resolution Systems (Part 6 Of

Chapter 4 TV and HRS Technologies INTRODUCTION picture on the TV screen by scanning electron beams (one for each primary color) across the picture tube As an entertainment medium, HDTV is not and varying their intensity in exact synchronism revolutionary. It is simply another step in the with the original picture signal. ongoing evolution of television that began with black and white (B&W) TV in the 1940s and will The 1950s technologies used today to bring color continue into the future with as yet undreamed of TV pictures to the home have a variety of shortcom- technologies. Each successive generation of TV ings and imperfections that modern systems can technology attempts to provide a more realistic correct. TV production formats, established in the picture and sound within the constraints of low-cost, 1930s and 40s, were originally based on 35-mm easy-to-use consumer technology. motion picture film. This gave today’s TV picture its Here we describe conventional NTSC1 television, nearly square shape (or aspect ratio) of 4 units wide Advanced Television (ATV) systems, and some of by 3 high (4:3). Research has found, however, a their underlying technologies (box 4-l). The conver- strong viewer preference for screens 5 to 6 units gence of ATVS, computer and telecommunications wide by 3 units high—as seen in today’s theatres— equipment toward High Resolution Systems (HRS) that correspond to the human field of vision.4 is discussed later. The original motion picture standard was 16 CONVENTIONAL TELEVISION: pictures per second—manually cranked cameras could go no faster.5 At that rate the viewer saw a PRODUCTION, TRANSMISSION, significant ‘flicker’ in the picture displayed (hence AND RECEPTION the term, the ‘flicks’ ‘).6 In developing TV transmis- Television systems involve three distinct activi- sion standards, engineers sought a system that sent ties: l)production, 2) transmission, and 3) display of pictures often enough that viewers did not see them the TV program. -

Game On: an Analysis of the Video Game Console Industry

Of Hedgehogs and Plumbers: An Investigation of Marketing Strategies in the American Home Console Industry By: Daniel DeMaiolo Michael G. Pontikos ADVER 3711 Marketing Communications Research April 23, 2008 Daniel DeMaiolo Michael G. Pontikos ADVER 3711 23 April 2008 Of Hedgehogs and Plumbers: An Investigation of Marketing Strategies in the American Home Console Industry From rescuing damsels in distress locked away in castles, slaying foul monsters in mythic lands, zooming through loop-de-loops in bizarre environments to realistic simulations of everyday life, the American video game home console industry emerges vibrant as ever. Even more interesting is the ability of such tiny pixels and sound bits to capture American minds and wallets. Through examination of the origin of the industry and the subsequent targeting, pricing, and positioning strategies, a portrait of the lucrative home video game console industry emerges. Although many of the major home console manufacturers over the years share a similar goal of selling home consoles to consumers, most of the corporations began in a completely different industry long before the birth of the gaming business and the subsequent console wars. To illustrate, Nintendo Co., Ltd. initially manufactured playing cards in 1889 “called ‘Hanafuda’ [which were] tenderly hand crafted using the bark from the mulberry and mitsu-mata trees” and later expanded to “love hotels” and “instant rice” (N-Sider Media, “Nintendo”). In addition, Sega Corporation, formerly known as Honolulu-based Standard Games in 1940, “began importing jukeboxes to supply American military bases in Japan…[and] eventually expanded into amusement game imports [with the slogan] ‘service and games’ ” from which their name is taken (Pollack, “Sega”). -

Technology, Media and Telecommunications Review

Telecommunications Review Telecommunications the Technology, Media and and Media Technology, Technology, Media and Telecommunications Review Eleventh Edition Editor Matthew T Murchison Eleventh Edition lawreviews © 2020 Law Business Research Ltd Technology, Media and Telecommunications Review Eleventh Edition Reproduced with permission from Law Business Research Ltd This article was first published in December 2020 For further information please contact [email protected] Editor Matthew T Murchison lawreviews © 2020 Law Business Research Ltd PUBLISHER Tom Barnes SENIOR BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT MANAGER Nick Barette BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT MANAGER Joel Woods SENIOR ACCOUNT MANAGERS Pere Aspinall, Jack Bagnall ACCOUNT MANAGERS Olivia Budd, Katie Hodgetts, Reece Whelan PRODUCT MARKETING EXECUTIVE Rebecca Mogridge RESEARCH LEAD Kieran Hansen EDITORIAL COORDINATOR Gavin Jordan PRODUCTION AND OPERATIONS DIRECTOR Adam Myers PRODUCTION EDITOR Anna Andreoli SUBEDITOR Martin Roach CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Nick Brailey Published in the United Kingdom by Law Business Research Ltd, London Meridian House, 34–35 Farringdon Street, London, EC4A 4HL, UK © 2020 Law Business Research Ltd www.TheLawReviews.co.uk No photocopying: copyright licences do not apply. The information provided in this publication is general and may not apply in a specific situation, nor does it necessarily represent the views of authors’ firms or their clients. Legal advice should always be sought before taking any legal action based on the information provided. The publishers -

Radio for the 1990S: Legal Strategies in an Emerging Global Marketplace Thomas Joseph Cryan

University of Miami Law School Institutional Repository University of Miami Inter-American Law Review 7-1-1991 Radio for the 1990s: Legal Strategies in an Emerging Global Marketplace Thomas Joseph Cryan Susan V. Massey James S. Crane Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr Recommended Citation Thomas Joseph Cryan, Susan V. Massey, and James S. Crane, Radio for the 1990s: Legal Strategies in an Emerging Global Marketplace, 22 U. Miami Inter-Am. L. Rev. 377 (1991) Available at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umialr/vol22/iss2/9 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Inter- American Law Review by an authorized administrator of Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 377 SPECIAL FEATURE RADIO FOR THE 1990s: LEGAL STRATEGIES IN AN EMERGING GLOBAL MARKETPLACE THOMAS JOSEPH CRYAN* SUSAN V. MASSEY** JAMES S. CRANE*** I. INTRODUCTION ................. 378 II. THE CURENT TECHNOLOGICAL STAGE.. ......................... 381 A. Amplitude Modulation ....... ......................... 381 B. Frequency Modulation ........... ......................... 383 C. Satellite Distribution ........ 383 D. Digital Technology ............ 385 III. THE GLOBAL MARKEtPLACE ......... 387 A. The United States ............. 388 B . E urope ............... ...... 390 1. England ............... .......................I I 391 2. France .................. ......................... 392 3. Eastern Bloc Nations ... ......................... 393 C. Asia and Latin America ...... ......................... 395 IV. INTERNATIONAL REGULATORY REGIME 396 * President, Southwestern Broadcasting Corporation; J.D., University of Miami School of Law, 1984. J.D., University of Miami School of Law, 1991. *** General Counsel, Southwestern Broadcasting Corporation; J.D. Florida State University College of Law, 1983. INTER-AMERICAN LAW REVIEW [Vol. -

Journalism & Electronic Media

Journalism & Electronic Media Reporting Editorial/column writing Feature writing Investigative journalism Sports Newspaper Online journalism & Magazine Photo journalism Publishing Editing Proofreading Circulation Marketing/promotion Production Foreign correspondence Large circulation newspapers Local newspapers: • Dailies • Alternative weeklies Newspaper Wire services & Magazine Trade newspapers Online publishers Publishing Major publishers Employers Consumer magazines News magazines Specialized magazines Mechanical and industrial publications Work with a college newspaper, yearbook, or alumni publication. Take an active role, preferably leadership, in journalism organizations. Complete an internship with a publisher. Seek experience with on-campus or community Newspaper publications. Find a part-time or summer job with a newspaper, & Magazine magazine, or print shop. Publishing Obtain sales experience. Strategies Join a professional journalism organization. Demonstrate creative spirit, writing skills, verbal skills, and proofreading ability. Create a portfolio of writing samples. Consider obtaining a minor in photography for photojournalistic specialty. Editing Sales Book Promotion Publishing Publicity Production Subsidiary rights Publishers: • Tradebooks • Children’s books • Paperbacks • Textbooks Book • Periodicals Publishing Book clubs Employers University presses Religious presses Technical, scientific, or medical presses Internet sites Attend a summer publishing institute to sharpen skills and build contacts. Become familiar with -

Examining the Dynamics of the US Video Game Console Market

Can Nintendo Get its Crown Back? Examining the Dynamics of the U.S. Video Game Console Market by Samuel W. Chow B.S. Electrical Engineering, Kettering University, 1997 A.L.M. Extension Studies in Information Technology, Harvard University, 2004 Submitted to the System Design and Management Program, the Technology and Policy Program, and the Engineering Systems Division on May 11, 2007 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degrees of Master of Science in Engineering and Management and Master of Science in Technology and Policy at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology June 2007 C 2007 Samuel W. Chow. All rights reserved The author hereby grants to NIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now know and hereafter created. Signature of Author Samuel W. Chow System Design and Management Program, and Technology and Policy Program May 11, 2007 Certified by James M. Utterback David J. cGrath jr 9) Professor of Management and Innovation I -'hs Supervisor Accepted by Pat Hale Senior Lecturer in Engineering Systems - Director, System Design and Management Program Accepted by Dava J. Newman OF TEOHNOLoGY Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics and Engineering Systems Director, Technology and Policy Program FEB 1 E2008 ARCHNOE LIBRARIES Can Nintendo Get its Crown Back? Examining the Dynamics of the U.S. Video Game Console Market by Samuel W. Chow Submitted to the System Design and Management Program, the Technology and Policy Program, and the Engineering Systems Division on May 11, 2007 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degrees of Master of Science in Engineering and Management and Master of Science in Technology and Policy Abstract Several generations of video game consoles have competed in the market since 1972. -

LESSON 1 Mass Media. Definition

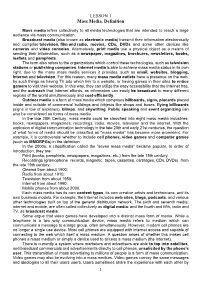

LESSON 1 Mass Media. Definition Mass media refers collectively to all media technologies that are intended to reach a large audience via mass communication. Broadcast media (also known as electronic media) transmit their information electronically and comprise television, film and radio, movies, CDs, DVDs and some other devices like cameras and video consoles. Alternatively, print media use a physical object as a means of sending their information, such as a newspaper, magazines, brochures, newsletters, books, leaflets and pamphlets. The term also refers to the organizations which control these technologies, such as television stations or publishing companies. Internet media is able to achieve mass media status in its own right, due to the many mass media services it provides, such as email, websites, blogging, Internet and television. For this reason, many mass media outlets have a presence on the web, by such things as having TV ads which link to a website, or having games in their sites to entice gamers to visit their website. In this way, they can utilize the easy accessibility that the Internet has, and the outreach that Internet affords, as information can easily be broadcast to many different regions of the world simultaneously and cost-efficiently. Outdoor media is a form of mass media which comprises billboards, signs, placards placed inside and outside of commercial buildings and /objects like shops and buses, flying billboards (signs in tow of airplanes), blimps, and skywriting. Public speaking and event organizing can also be considered as forms of mass media. In the late 20th Century, mass media could be classified into eight mass media industries: books, newspapers, magazines, recordings, radio, movies, television and the internet.