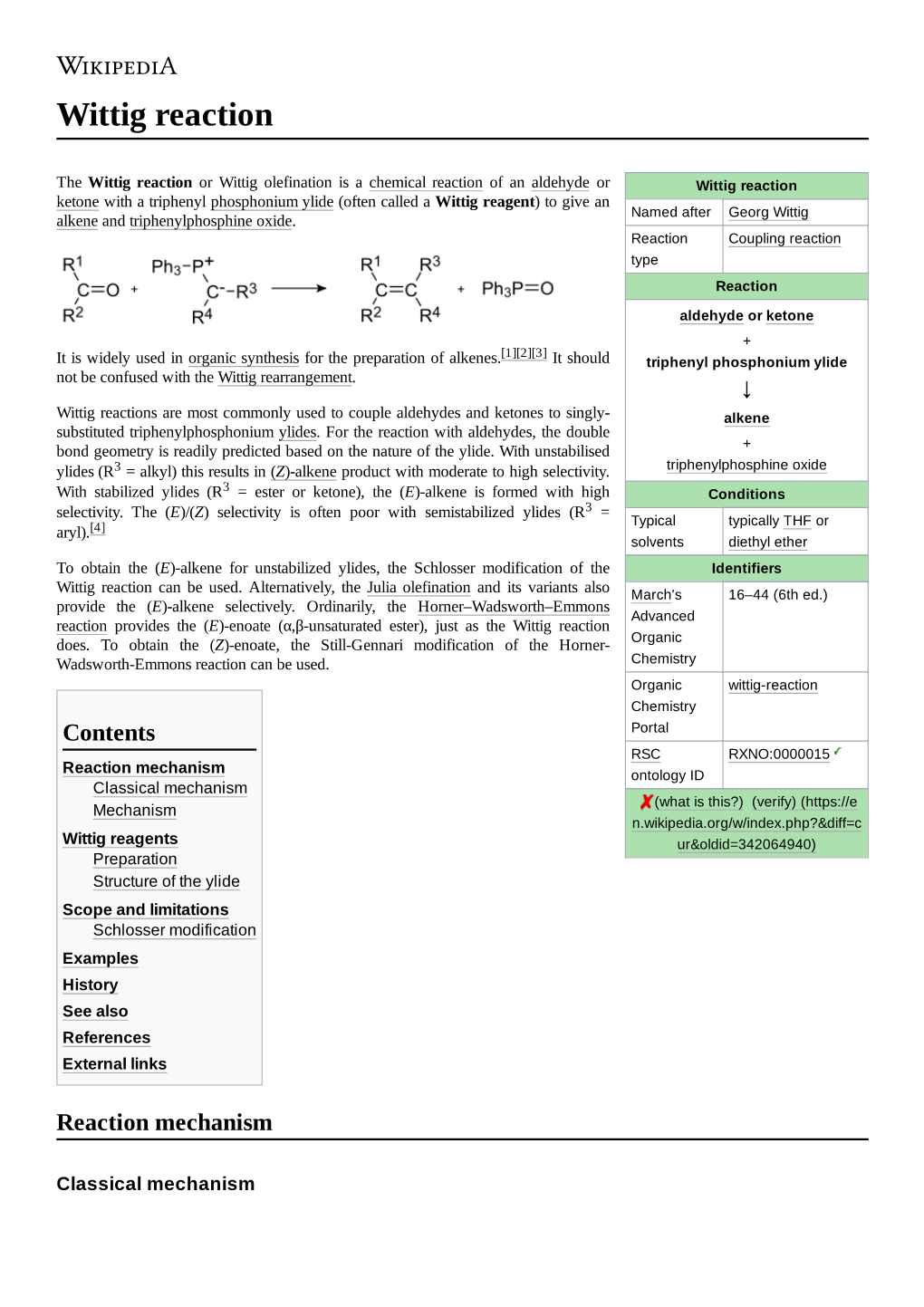

Wittig Reaction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Socit Chimique De France 2014 Prize Winners

Angewandte. Angewandte News Chemie Socit Chimique de France 2014 Prize Nazario Martn (Universidad Complutense de Winners Madrid) is the winner of the Prix franco-espagnol Awarded … Miguel Cataln–Paul Sabatier. Martn was featured The Socit Chimique de France has announced its here when he was awarded the 2012 EuCheMS 2014 prize winners. We congratulate all the awar- Lectureship.[4a] Martn is on the International dees and feature our authors and referees here. Advisory Boards of Chemistry—An Asian Journal, Max Malacria (Institut de Chimie des Substan- ChemPlusChem, and ChemSusChem. His report on ces Naturelles; ICSN) is the winner of the Prix modified single-wall nanotubes was recently fea- Joseph Achille Le Bel, which is awarded to tured on the cover of Chemistry—A European recognize internationally recognized research. Mal- Journal.[4b] acria studied at the Universit Aix-Marseille III, Michael Holzinger (Universit Joseph Four- where he completed his PhD under the supervision nier, Grenoble 1; UJF) is the winner of the Prix M. Malacria of Marcel Bertrand in 1974. From 1974–1981, he jeune chercheur from the Analytical Chemistry was matre-assistant with Jacques Gore at the Division. Holzinger carried out his PhD at the Universit Claude Bernard Lyon 1 (UCBL), and Friedrich-Alexander-Universitt Erlangen-Nrn- from 1981–1983, he carried out postdoctoral berg. After postdoctoral research at the Universit research with K. Peter C. Vollhardt at the Univer- Montpellier 2 (UM2) and the Max Planck Institute sity of California, Berkeley. He returned to the for Solid-State Research, and working at Robert UCBL as matre de conferences in 1983, and was Bosch, he joined Serge Cosniers group at the UJF made professor at the Universit Pierre et Marie as a CNRS charg de recherche. -

Catalytic Asymmetric Di Hydroxylation

Chem. Rev. 1994, 94, 2483-2547 2483 Catalytic Asymmetric Dihydroxylation Hartmuth C. Kolb,t Michael S. VanNieuwenhze,* and K. Barry Sharpless* Department of Chemistry, The Scripps Research Institute, 10666 North Torfey Pines Road, La Jolla, California 92037 Received Ju/y 28, 1994 (Revised Manuscript Received September 14, 1994) Contents 3.1.4. Differentiation of the Hydroxyl Groups by 2524 Selective, Intramolecular Trapping 1. Introduction and General Principles 2483 3.1.5. Miscellaneous Transformations 2525 2. Enantioselective Preparation of Chiral 1,2-Diols 2489 3.2. Preparation of Chiral Building Blocks 2527 from Olefins 3.2.1. Electrophilic Building Blocks 2527 2.1. Preparation of Ligands, Choice of Ligand, 2489 Scope, and Limitations 3.2.2. Chiral Diol and Polyol Building Blocks 2529 2.1.1. Preparation of the Ligands 2490 3.2.3. Chiral Monohydroxy Compounds Derived 2529 from Diols 2.1 -2. Ligand Choice and Enantioselectivity Data 2490 3.2.4. 5- and 6-Membered Heterocycles 2530 2.1.3. Limitations 2491 3.3. Preparation of Chiral Auxiliaries for Other 2530 2.2. Reaction Conditions 2493 Asymmetric Transformations 2.2.1. Asymmetric Dihydroxylation of the 2493 3.3.1. Preparation of 2530 “Standard Substrates” (1 R,2S)-trans-2-phenylcyclohexanol 2.2.2. Asymmetric Dihydroxylation of 2496 3.3.2. Optically Pure Hydrobenzoin (Stilbenediol) 2531 Tetrasubstituted Olefins, Including Enol and Derivatives Ethers 4. Recent Applications: A Case Study 2536 2.2.3. Asymmetric Dihydroxylation of 2496 Electron-Deficient Olefins 5. Conclusion 2538 2.2.4. Chemoselectivity in the AD of Olefins 2497 6. References and Footnotes 2542 Containing Sulfur 2.3. -

A Nobel Synthesis

MILESTONES IN CHEMISTRY Ian Grayson A nobel synthesis IAN GRAYSON Evonik Degussa GmbH, Rodenbacher Chaussee 4, Hanau-Wolfgang, 63457, Germany he first Nobel Prize for chemistry was because it is a scientific challenge, as he awarded in 1901 (to Jacobus van’t Hoff). described in his Nobel lecture: “The synthesis T Up to 2010, the chemistry prize has been of brazilin would have no industrial value; awarded 102 times, to 160 laureates, of whom its biological importance is problematical, only four have been women (1). The most but it is worth while to attempt it for the prominent area for awarding the Nobel Prize sufficient reason that we have no idea how for chemistry has been in organic chemistry, in to accomplish the task” (4). which the Nobel committee includes natural Continuing the list of Nobel Laureates in products, synthesis, catalysis, and polymers. organic synthesis we arrive next at R. B. This amounts to 24 of the prizes. Reading the Woodward. Considered by many the greatest achievements of the earlier organic chemists organic chemist of the 20th century, he who were recipients of the prize, we see that devised syntheses of numerous natural they were drawn to synthesis by the structural Alfred Nobel, 1833-1896 products, including lysergic acid, quinine, analysis and characterisation of natural cortisone and strychnine (Figure 1). 6 compounds. In order to prove the structure conclusively, some In collaboration with Albert Eschenmoser, he achieved the synthesis, even if only a partial synthesis, had to be attempted. It is synthesis of vitamin B12, a mammoth task involving nearly 100 impressive to read of some of the structures which were deduced students and post-docs over many years. -

Organic Seminar Abstracts

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://archive.org/details/organicsemin1971752univ / a ORGANIC SEMINAR ABSTRACTS 1971-1972 Semester II School of Chemical Sciences Department of Chemistry- University of Illinois Urbana, Illinois 3 SEMINAR TOPICS II Semester 1971-72 Reactions of Alkyl Ethers Involving n- Complexes on a Reaction Pathway 125 Jerome T. Adams New Syntheses of Helicenes 127 Alan Morrice Recent Advances in Drug Detection and Analysis I36 Ronald J. Convers The Structure of Carbonium Ions with Multiple Neighboring Groups 138 William J. Work Recent Reactions of the DMSO-DCC Reagent ll+O James A. Franz Nucleophilic Acylation 1^2 Janet Ollinger The Chemistry of Camptothecin lU^ Dale Pigott Stereoselective Syntheses and Absolute Configuration of Cecropia Juvenile Horomone 1U6 John C. Greenfield Uleine and Related Aspidosperma Alkaloids 155 Glen Tolman Strategies in Oligonucleotide Synthesis 162 Graham Walker Stable Carbocations: C-13 Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Studies 16U Moses W. McMillan Organic Chlorosulfinates 166 Steven W. Moje Recent Advances in the Chemistry of Penicillins and Cephalosporins 168 Ronald Stroshane Cerium (iv) Oxidations 175 William C. Christopfel A New Total Synthesis of Vitamin D 18 William Graham Ketone Transpositions 190 Ann L. Crumrine - 125 - REACTIONS OF ALKYL ETHERS INVOLVING n-COMPLEXES ON A REACTION PATHWAY Reported by Jerome T. Adams February 2k 1972 The n-complex (l) has been described as an intermediate on the reaction pathway for electrophilic aromatic substitution and acid catalyzed rearrange- ment of alkyl aryl ethers along with sigma (2) and pi (3) type intermediates. 1 ' 2 +xR Physical evidence for the existence of n-complexes of alkyl aryl ethers was found in the observation of methyl phenyl ononium ions by nmr 3 and ir observation of n-complexes of anisole with phenol. -

Bridging Mcmurry and Wittig in One-Pot

Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 1755 Bridging McMurry and Wittig in One-Pot Olefins from Stereoselective, Reductive Couplings of Two Aldehydes via Phosphaalkenes JURI MAI ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS ISSN 1651-6214 ISBN 978-91-513-0536-3 UPPSALA urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-368873 2019 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Häggsalen, Ångströmlaboratoriet, Lägerhyddsvägen 1, Uppsala, Friday, 15 February 2019 at 10:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Professor Dr. Christian Müller (Freie Universität Berlin, Institute of Chemistry and Biochemistry). Abstract Mai, J. 2019. Bridging McMurry and Wittig in One-Pot. Olefins from Stereoselective, Reductive Couplings of Two Aldehydes via Phosphaalkenes. Digital Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 1755. 112 pp. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-513-0536-3. The formation of C=C bonds is of great importance for fundamental and industrial synthetic organic chemistry. There are many different methodologies for the construction of C=C bonds in the literature, but currently only the McMurry reaction allows the reductive coupling of two carbonyl compounds to form alkenes. This thesis contributes to the field of carbonyl olefinations and presents the development of a new synthetic protocol for a one-pot reductive coupling of two aldehydes to alkenes based on organophosphorus chemistry. The coupling reagent, a phosphanylphosphonate, reacts with an aldehyde to yield a phosphaalkene intermediate which upon activation with a base undergoes an olefination with a second aldehyde. A general overview of synthetic methods for carbonyl olefinations and the chemistry of phosphaalkenes is given in the background chapter. -

PDF (Chapter 1)

Chapter 1–Evolving Strategies Toward the Synthesis of Curcusone C 1 CHAPTER 1 Evolving Strategies Toward the Synthesis of Curcusone Ci 1.1 INTRODUCTION AND ALTERNATE SYNTHETIC STRATEGIES 1.1.1 INTRODUCTION Indigenous to Central America, the flowering plant Jatropha curcas has traditionally been used in the manufacturing of soaps and lamp oil but has also drawn attention due to its potential applications in the biodiesel industry.1 J. curcas has also received notice by organic chemists owing to its structurally diverse array of diterpenoid secondary metabolites, which includes the curcusone (i) This research was a collaborative effort between A. C. Wright and C. W. Lee, see: reference 6, reference 19, and reference 20. Chapter 1–Evolving Strategies Toward the Synthesis of Curcusone C 2 family of natural products. This family comprises various synthetically challenging and biologically active rhamnofolane diterpenoid natural products. In 1986, Naengchomnong and coworkers first isolated curcusones A–D (1–4, Figure 1.1.1) and elucidated the structures of 2 and 3 via X-ray diffraction.2 Over the ensuing three decades, several more members of this family were structurally identified and were further discovered to possess anticancer activity.3 Among them, curcusone C (3) demonstrates the most potent and varied anticancer properties, including anti- proliferative activity against human hepatoma (IC50 in 2.17 uM), ovarian carcinoma (IC50 in 0.160 2 uM), and promyeolycytic leukemia (IC50 in 1.36 uM). Figure 1.1.1. Reported Structures of Curcusones A–J O O H O H H H H H R2 H Me Me R1 HO MeO O O O R1, R2 = Me, H : Curcusone A (1) Curcusone E Curcusone F R1, R2 = H, Me : Curcusone B (2) R1, R2 = Me, OH : Curcusone C (3) R1, R2 = OH, Me : Curcusone D (4) O O O H H H H H H H R2 O OH R1 O OH MeO O O O Curcusone G Curcusone H R1, R2 = Me, H : Curcusone I (5) R1, R2 = H, Me : Curcusone J (6) Despite these enticing biological features, 3 and all of its structural relatives have yet to surrender to any total synthesis campaigns. -

Title Synthetic Studies on the Chemistry of Gem-Dimetalation with Inter-Element Compounds( Dissertation 全文 )

Synthetic Studies on the Chemistry of gem-Dimetalation with Title Inter-element Compounds( Dissertation_全文 ) Author(s) Kurahashi, Takuya Citation Kyoto University (京都大学) Issue Date 2003-03-24 URL http://dx.doi.org/10.14989/doctor.k10168 Right Type Thesis or Dissertation Textversion author Kyoto University Synthetic Studies on the Chemistry ofgem-Dimetalation with Inter-element Compounds Takuya Kurahashi 2003 Synthetic Studies on the Chemistry ofgem-Dimetalation with Inter-element Compounds Takuya Kurahashi 2003 Contents Chapter 1 Introduction and General Summary 1 Chapter 2 Silylborylation and Diborylation of Alkylidene-type Carbenoids. Synthesis of 1-Boryl-1-silyl-1-alkenes and 1,1-Diboryl-1-alkenes 21 Chapter 3 Stereospecific Silylborylation of a-Chloroallyllithiums. Synthesis and Reactions of Allylic gem-Silylborylated Reagents 53 Chapter 4 Synthesis and Reactions of 1-Silyl-1-borylallenes 81 Chapter 5 Efficient Synthesis of 2,3-Diboryl-1,3-butadiene and Synthetic Applications 95 List ofPublications - 115 Acknowledgments - 117 Abbreviations Ac acetyl J coupling constant in Hz Anal. element analysis LDA lithium diisopropylamide aq. aqueous m multiplet (spectral) Bn benzyl M mol per liter Bpin 4,4,5,5-tetramethyl-I,3,2-dioxabolan-2-yl Me methyl brs broad singlet (spectral) MEM 2-methoxyethoxymethyI Bu butyl min minute(s) calcd calculated mL mililiter cat. catalytic mp melting point Cy cyclohexyl Ms mesyl d doublet (spectral) NMR nuclear magnetic resonance dba dibenzylideneacetone Pent pentyl DME 1,2,-dimethoxyethane Ph phenyl DMF N,N-dimethylformamide -

GEORG WITTIG Heidelberg, Federal Republic of Germany Translation from the German Text

FROM DIYLS TO YLIDES TO MY IDYLL Nobel Lecture, 8 December 1979 by GEORG WITTIG Heidelberg, Federal Republic of Germany Translation from the German text Chemical research and mountaineering have much in common. If the goal or the summit is to be reached, both initiative and determination as well as perseverance are required. But after the hard work it is a great joy to be at the goal or the peak with its splendid panorama. However, especially in chemical research - as far as new territory is concerned - the results may sometimes be quite different: they may be disappointing or delightful. Looking back at my work in scientific research, I will confine this talk to the positive results (1). Some 50 years ago I was fascinated by an idea which I investigated experi- mentally. The question was how ring strain acts on a ring if an accumulation of phenyl groups at two neighboring carbon atoms weakens the C-C linkage and predisposes to the formation of a diradical (for brevity called diyl) (Fig. 1). Among the many experimental results (2) I choose the synthesis of the hydrocarbons 1 and 4 (3), which we thought capable of diyl formation. Starting materials were appropriate dicarboxylic esters, which we transformed into the corresponding glycols. While these were obtained under the influence of phenylmagnesium halide only in modest yield, phenyllithium proved to be superior and was readily accessible by the method of K. Ziegler, using bromobenzene and lithium. The glycolates resulting from the reaction with potassium phenylisopropylide formed - on heating with methyl iodide - the corresponding dimethyl ethers, which supplied the equivalent hydrocarbons 1 and 4 by alkali metal splitting and demetalation with tetramethylethylene dibromide. -

Nickel-Catalyzed Hydrosilylation of Alkenes and Transition-Metal-Free

Nickel-catalyzed Hydrosilylation of Alkenes and Transition- Metal-Free Intermolecular α-C-H Amination of Ethers THÈSE NO 7129 (2016) PRÉSENTÉE LE 28 JUILLET 2016 À LA FACULTÉ DES SCIENCES DE BASE LABORATOIRE DE SYNTHÈSE ET DE CATALYSE INORGANIQUE PROGRAMME DOCTORAL EN CHIMIE ET GÉNIE CHIMIQUE ÉCOLE POLYTECHNIQUE FÉDÉRALE DE LAUSANNE POUR L'OBTENTION DU GRADE DE DOCTEUR ÈS SCIENCES PAR Ivan BUSLOV acceptée sur proposition du jury: Prof. K. Severin, président du jury Prof. X. Hu, directeur de thèse Prof. E. P. Kündig, rapporteur Prof. M. Driess, rapporteur Prof. H.-A. Klok, rapporteur Suisse 2016 Acknowledgements First, I would like to thank my scientific advisor, Prof. Xile Hu, for giving me the opportunity to carry out my doctoral studies in his group. I am deeply grateful for his support, encouragement and guidance during my time as a Ph.D. student at EPFL. His optimistic energy and confidence in my research always inspired me and helped me to move forward. I would like to thank my thesis jury: Prof. Kay Severin, Prof. Ernst Peter Kündig, Prof. Matthias Driess and Prof. Harm-Anton Klok for accepting to examine this manuscript. Many thanks to the people working at EPFL: Annelise Carrupt, Gladys Pache and Benjamin Kronenberg - the team of BCH chemical store - for their excellent work; Dr. Pascal Miéville for his help with NMR machines and methods; Dr. Rosario Scopelliti and Dr. Euro Solari for performing the X-ray and elemental analyses; Dr. Laure Menin, Daniel Baumann and Francisco Sepulveda for the mass spectrometry analyses; Christina Zamanos-Epremian and Anne Lene Odegaard for their kind support and for the administrative work. -

The Emergence of the Structure of the Molecule and the Art of Its Synthesis

Total Synthesis DOI: 10.1002/anie.200((will be filled in by the editorial staff)) The Emergence of the Structure of the Molecule and the Art of Its Synthesis K. C. Nicolaou* At the core of the science of chemistry lie the structure of the molecule, the art of its synthesis, and the design of function within it. These attributes elevate chemistry to an essential, indispensable, and powerful discipline whose impact on the life and materials sciences is paramount, undisputed, and expanding. Indeed, today the combination of structure, synthesis, and function is driving many scientific frontiers forward, including drug discovery and development, biology and biotechnology, materials science and nanotechnology, and molecular devices of all kinds. What connects structure and function is synthesis, whose flagship is total synthesis, the art of constructing the molecules of nature and their derivatives. The power of chemical synthesis at any given time is reflected and symbolized by the state of the art of total synthesis, and as such the condition and sophistication of the latter needs to be continuously nourished and advanced. In this review the understanding of the structure of the molecule, the emergence of organic synthesis, and the art of total synthesis are traced from the nineteenth century to the present day. 1. Introduction other sciences, technologies, and engineering, and how did it come to be so advanced and enabling? The power of chemistry is The celebration of Angewandte Chemie’s 125th anniversary in primarily derived from its ability to understand molecular structure, 2013 gives us the opportunity to reflect on both the past and the synthesize it, and build function within it through molecular design future of the central, and yet universal and ubiquitous, science of and synthesis. -

The Ziegler Catalysts Serendipity Or Systematic Research?

GENERAL ARTICLE The Ziegler Catalysts Serendipity or Systematic Research? S Sivaram Fifty-four years after the Nobel Prize was awarded to Karl Ziegler and Giulio Natta for the polymerization of olefins by complex organometallic catalysts, the field continues to elicit enormous interest, both from the academia and the indus- try. Furthermore, this chemistry and technology occupy a high ground in the annals of 20th-century science. The el- S Sivaram is currently a egance and simplicity of Ziegler’s chemistry continue to as- Honorary Professor and tound researchers even today, and the enormous impact this INSA Senior Scientist at the chemistry has had on the quality of our life is truly incred- Indian Institute of Science Education and Research, ible. Polyethylene, produced using Ziegler’s chemistry has Pune. Prior to this, he was a touched every aspect of common man’s life, so much so that, CSIR-Bhatnagar Fellow today it is impossible to imagine life on this planet without (2011–16) and Director of polyethylene. Equally fascinating is the story of how Ziegler CSIR-NCL (2002–10). Apart from pursuing research in stumbled on this most impactful discovery. Ziegler’s disci- polymer chemistry, Sivaram pline and rigor in systematically following every lead in the is a keen student of history of laboratory, however trivial it seemed, and his penchant for science and the origin and understanding the basics of science culminated in 1954, with evolution of thoughts that drive the scientific enterprise. a simple reaction for converting ethylene to polyethylene, the (www.swaminathansivaram.in) quintessential carbon-carbon (C-C) bond forming reaction. -

Image-Brochure-LNLM-2020-LQ.Pdf

NOBEL LAUREATES PARTICIPATING IN LINDAU EVENTS SINCE 1951 Peter Agre | George A. Akerlof | Kurt Alder | Zhores I. Alferov | Hannes Alfvén | Sidney Altman | Hiroshi Amano | Philip W. Anderson | Christian B. Anfinsen | Edward V. Appleton | Werner Arber | Frances H. Arnold | Robert J. Aumann | Julius Axelrod | Abhijit Banerjee | John Bardeen | Barry C. Barish | Françoise Barré-Sinoussi | Derek H. R. Barton | Nicolay G. Basov | George W. Beadle | J. Georg Bednorz | Georg von Békésy |Eric Betzig | Bruce A. Beutler | Gerd Binnig | J. Michael Bishop | James W. Black | Elizabeth H. Blackburn | Patrick M. S. Blackett | Günter Blobel | Konrad Bloch | Felix Bloch | Nicolaas Bloembergen | Baruch S. Blumberg | Niels Bohr | Max Born | Paul Boyer | William Lawrence Bragg | Willy Brandt | Walter H. Brattain | Bertram N. Brockhouse | Herbert C. Brown | James M. Buchanan Jr. | Frank Burnet | Adolf F. Butenandt | Melvin Calvin Thomas R. Cech | Martin Chalfie | Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar | Pavel A. Cherenkov | Steven Chu | Aaron Ciechanover | Albert Claude | John Cockcroft | Claude Cohen- Tannoudji | Leon N. Cooper | Carl Cori | Allan M. Cormack | John Cornforth André F. Cournand | Francis Crick | James Cronin | Paul J. Crutzen | Robert F. Curl Jr. | Henrik Dam | Jean Dausset | Angus S. Deaton | Gérard Debreu | Petrus Debye | Hans G. Dehmelt | Johann Deisenhofer Peter A. Diamond | Paul A. M. Dirac | Peter C. Doherty | Gerhard Domagk | Esther Duflo | Renato Dulbecco | Christian de Duve John Eccles | Gerald M. Edelman | Manfred Eigen | Gertrude B. Elion | Robert F. Engle III | François Englert | Richard R. Ernst Gerhard Ertl | Leo Esaki | Ulf von Euler | Hans von Euler- Chelpin | Martin J. Evans | John B. Fenn | Bernard L. Feringa Albert Fert | Ernst O. Fischer | Edmond H. Fischer | Val Fitch | Paul J.