Draft Environmental Assessment and Land Protection for the Flint Hills Legacy Conservation Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State of Colorado 2016 Wetland Plant List

5/12/16 State of Colorado 2016 Wetland Plant List Lichvar, R.W., D.L. Banks, W.N. Kirchner, and N.C. Melvin. 2016. The National Wetland Plant List: 2016 wetland ratings. Phytoneuron 2016-30: 1-17. Published 28 April 2016. ISSN 2153 733X http://wetland-plants.usace.army.mil/ Aquilegia caerulea James (Colorado Blue Columbine) Photo: William Gray List Counts: Wetland AW GP WMVC Total UPL 83 120 101 304 FACU 440 393 430 1263 FAC 333 292 355 980 FACW 342 329 333 1004 OBL 279 285 285 849 Rating 1477 1419 1504 1511 User Notes: 1) Plant species not listed are considered UPL for wetland delineation purposes. 2) A few UPL species are listed because they are rated FACU or wetter in at least one Corps Region. 3) Some state boundaries lie within two or more Corps Regions. If a species occurs in one region but not the other, its rating will be shown in one column and the other column will be BLANK. Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. 1/22 5/12/16 Scientific Name Authorship AW GP WMVC Common Name Abies bifolia A. Murr. FACU FACU Rocky Mountain Alpine Fir Abutilon theophrasti Medik. UPL UPL FACU Velvetleaf Acalypha rhomboidea Raf. FACU FACU Common Three-Seed-Mercury Acer glabrum Torr. FAC FAC FACU Rocky Mountain Maple Acer grandidentatum Nutt. FACU FAC FACU Canyon Maple Acer negundo L. FACW FAC FAC Ash-Leaf Maple Acer platanoides L. UPL UPL FACU Norw ay Maple Acer saccharinum L. FAC FAC FAC Silver Maple Achillea millefolium L. FACU FACU FACU Common Yarrow Achillea ptarmica L. -

Comparative Ecomorphology and Biogeography of Herpestidae and Viverridae (Carnivora) in Africa and Asia

Comparative Ecomorphology and Biogeography of Herpestidae and Viverridae (Carnivora) in Africa and Asia Gina D. Wesley-Hunt1, Reihaneh Dehghani2,3 and Lars Werdelin3 1Biology Department, Montgomery College, 51 Mannakee St. Rockville, Md. 20850, USA; 2Department of Zoology, Stockholm University, SE-106 91, Stockholm, Sweden; 3Department of Palaeozoology, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Box 50007, SE-104 05, Stockholm, Sweden INTRODUCTION Ecological morphology (ecomorphology) is a powerful tool for exploring diversity, ecology and evolution in concert (Wainwright, 1994, and references therein). Alpha taxonomy and diversity measures based on taxon counting are the most commonly used tools for understanding long-term evolutionary patterns and provide the foundation for all other biological studies above the organismal level. However, this provides insight into only a single dimension of a multidimensional system. As a complement, ecomorphology allows us to describe the diversification and evolution of organisms in terms of their morphology and ecological role. This is accomplished by using quantitative and semi-quantitative characterization of features of organisms that are important, for example, in niche partitioning or resource utilization. In this context, diversity is commonly referred to as disparity (Foote, 1993). The process of speciation, for example, can be better understood and hypotheses more rigorously tested, if it can be quantitatively demonstrated whether a new species looks very similar to the original taxon or whether its morphology has changed in a specific direction. For example, if a new species of herbivore evolves with increased grinding area in the cheek dentition, it can either occupy the same area of morphospace as previously existing species, suggesting increased resource competition, or it can occupy an area of morphospace that had previously been empty, suggesting evolution into a new niche. -

(Barbourofelinae, Nimravidae, Carnivora), from the Middle Miocene of China Suggests Barbourofelines Are Nimravids, Not Felids

UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works Title A new genus and species of sabretooth, Oriensmilus liupanensis (Barbourofelinae, Nimravidae, Carnivora), from the middle Miocene of China suggests barbourofelines are nimravids, not felids Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0g62362j Journal JOURNAL OF SYSTEMATIC PALAEONTOLOGY, 18(9) ISSN 1477-2019 Authors Wang, Xiaoming White, Stuart C Guan, Jian Publication Date 2020-05-02 DOI 10.1080/14772019.2019.1691066 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Journal of Systematic Palaeontology ISSN: 1477-2019 (Print) 1478-0941 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tjsp20 A new genus and species of sabretooth, Oriensmilus liupanensis (Barbourofelinae, Nimravidae, Carnivora), from the middle Miocene of China suggests barbourofelines are nimravids, not felids Xiaoming Wang, Stuart C. White & Jian Guan To cite this article: Xiaoming Wang, Stuart C. White & Jian Guan (2020): A new genus and species of sabretooth, Oriensmilusliupanensis (Barbourofelinae, Nimravidae, Carnivora), from the middle Miocene of China suggests barbourofelines are nimravids, not felids , Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, DOI: 10.1080/14772019.2019.1691066 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14772019.2019.1691066 View supplementary material Published online: 08 Jan 2020. Submit your article to this journal View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tjsp20 Journal of Systematic Palaeontology, 2020 Vol. 0, No. 0, 1–21, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14772019.2019.1691066 A new genus and species of sabretooth, Oriensmilus liupanensis (Barbourofelinae, Nimravidae, Carnivora), from the middle Miocene of China suggests barbourofelines are nimravids, not felids a,bà c d Xiaoming Wang , Stuart C. -

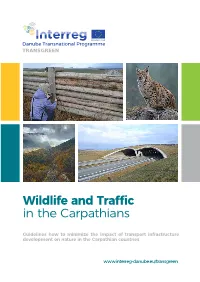

Guidelines for Wildlife and Traffic in the Carpathians

Wildlife and Traffic in the Carpathians Guidelines how to minimize the impact of transport infrastructure development on nature in the Carpathian countries Wildlife and Traffic in the Carpathians Guidelines how to minimize the impact of transport infrastructure development on nature in the Carpathian countries Part of Output 3.2 Planning Toolkit TRANSGREEN Project “Integrated Transport and Green Infrastructure Planning in the Danube-Carpathian Region for the Benefit of People and Nature” Danube Transnational Programme, DTP1-187-3.1 April 2019 Project co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) www.interreg-danube.eu/transgreen Authors Václav Hlaváč (Nature Conservation Agency of the Czech Republic, Member of the Carpathian Convention Work- ing Group for Sustainable Transport, co-author of “COST 341 Habitat Fragmentation due to Trans- portation Infrastructure, Wildlife and Traffic, A European Handbook for Identifying Conflicts and Designing Solutions” and “On the permeability of roads for wildlife: a handbook, 2002”) Petr Anděl (Consultant, EVERNIA s.r.o. Liberec, Czech Republic, co-author of “On the permeability of roads for wildlife: a handbook, 2002”) Jitka Matoušová (Nature Conservation Agency of the Czech Republic) Ivo Dostál (Transport Research Centre, Czech Republic) Martin Strnad (Nature Conservation Agency of the Czech Republic, specialist in ecological connectivity) Contributors Andriy-Taras Bashta (Biologist, Institute of Ecology of the Carpathians, National Academy of Science in Ukraine) Katarína Gáliková (National -

The 2008 IUCN Red Listings of the World's Small Carnivores

The 2008 IUCN red listings of the world’s small carnivores Jan SCHIPPER¹*, Michael HOFFMANN¹, J. W. DUCKWORTH² and James CONROY³ Abstract The global conservation status of all the world’s mammals was assessed for the 2008 IUCN Red List. Of the 165 species of small carni- vores recognised during the process, two are Extinct (EX), one is Critically Endangered (CR), ten are Endangered (EN), 22 Vulnerable (VU), ten Near Threatened (NT), 15 Data Deficient (DD) and 105 Least Concern. Thus, 22% of the species for which a category was assigned other than DD were assessed as threatened (i.e. CR, EN or VU), as against 25% for mammals as a whole. Among otters, seven (58%) of the 12 species for which a category was assigned were identified as threatened. This reflects their attachment to rivers and other waterbodies, and heavy trade-driven hunting. The IUCN Red List species accounts are living documents to be updated annually, and further information to refine listings is welcome. Keywords: conservation status, Critically Endangered, Data Deficient, Endangered, Extinct, global threat listing, Least Concern, Near Threatened, Vulnerable Introduction dae (skunks and stink-badgers; 12), Mustelidae (weasels, martens, otters, badgers and allies; 59), Nandiniidae (African Palm-civet The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species is the most authorita- Nandinia binotata; one), Prionodontidae ([Asian] linsangs; two), tive resource currently available on the conservation status of the Procyonidae (raccoons, coatis and allies; 14), and Viverridae (civ- world’s biodiversity. In recent years, the overall number of spe- ets, including oyans [= ‘African linsangs’]; 33). The data reported cies included on the IUCN Red List has grown rapidly, largely as on herein are freely and publicly available via the 2008 IUCN Red a result of ongoing global assessment initiatives that have helped List website (www.iucnredlist.org/mammals). -

Vascular Plants and a Brief History of the Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands

United States Department of Agriculture Vascular Plants and a Brief Forest Service Rocky Mountain History of the Kiowa and Rita Research Station General Technical Report Blanca National Grasslands RMRS-GTR-233 December 2009 Donald L. Hazlett, Michael H. Schiebout, and Paulette L. Ford Hazlett, Donald L.; Schiebout, Michael H.; and Ford, Paulette L. 2009. Vascular plants and a brief history of the Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS- GTR-233. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 44 p. Abstract Administered by the USDA Forest Service, the Kiowa and Rita Blanca National Grasslands occupy 230,000 acres of public land extending from northeastern New Mexico into the panhandles of Oklahoma and Texas. A mosaic of topographic features including canyons, plateaus, rolling grasslands and outcrops supports a diverse flora. Eight hundred twenty six (826) species of vascular plant species representing 81 plant families are known to occur on or near these public lands. This report includes a history of the area; ethnobotanical information; an introductory overview of the area including its climate, geology, vegetation, habitats, fauna, and ecological history; and a plant survey and information about the rare, poisonous, and exotic species from the area. A vascular plant checklist of 816 vascular plant taxa in the appendix includes scientific and common names, habitat types, and general distribution data for each species. This list is based on extensive plant collections and available herbarium collections. Authors Donald L. Hazlett is an ethnobotanist, Director of New World Plants and People consulting, and a research associate at the Denver Botanic Gardens, Denver, CO. -

Evolutionary History of Carnivora (Mammalia, Laurasiatheria) Inferred

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.05.326090; this version posted October 5, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. This article is a US Government work. It is not subject to copyright under 17 USC 105 and is also made available for use under a CC0 license. 1 Manuscript for review in PLOS One 2 3 Evolutionary history of Carnivora (Mammalia, Laurasiatheria) inferred 4 from mitochondrial genomes 5 6 Alexandre Hassanin1*, Géraldine Véron1, Anne Ropiquet2, Bettine Jansen van Vuuren3, 7 Alexis Lécu4, Steven M. Goodman5, Jibran Haider1,6,7, Trung Thanh Nguyen1 8 9 1 Institut de Systématique, Évolution, Biodiversité (ISYEB), Sorbonne Université, 10 MNHN, CNRS, EPHE, UA, Paris. 11 12 2 Department of Natural Sciences, Faculty of Science and Technology, Middlesex University, 13 United Kingdom. 14 15 3 Centre for Ecological Genomics and Wildlife Conservation, Department of Zoology, 16 University of Johannesburg, South Africa. 17 18 4 Parc zoologique de Paris, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris. 19 20 5 Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, IL, USA. 21 22 6 Department of Wildlife Management, Pir Mehr Ali Shah, Arid Agriculture University 23 Rawalpindi, Pakistan. 24 25 7 Forest Parks & Wildlife Department Gilgit-Baltistan, Pakistan. 26 27 28 * Corresponding author. E-mail address: [email protected] bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.05.326090; this version posted October 5, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. This article is a US Government work. -

Comparative Biology of Seed Dormancy-Break and Germination in Convolvulaceae (Asterids, Solanales)

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2008 COMPARATIVE BIOLOGY OF SEED DORMANCY-BREAK AND GERMINATION IN CONVOLVULACEAE (ASTERIDS, SOLANALES) Kariyawasam Marthinna Gamage Gehan Jayasuriya University of Kentucky, [email protected] Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Jayasuriya, Kariyawasam Marthinna Gamage Gehan, "COMPARATIVE BIOLOGY OF SEED DORMANCY- BREAK AND GERMINATION IN CONVOLVULACEAE (ASTERIDS, SOLANALES)" (2008). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 639. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/639 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Kariyawasam Marthinna Gamage Gehan Jayasuriya Graduate School University of Kentucky 2008 COMPARATIVE BIOLOGY OF SEED DORMANCY-BREAK AND GERMINATION IN CONVOLVULACEAE (ASTERIDS, SOLANALES) ABSRACT OF DISSERTATION A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Art and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Kariyawasam Marthinna Gamage Gehan Jayasuriya Lexington, Kentucky Co-Directors: Dr. Jerry M. Baskin, Professor of Biology Dr. Carol C. Baskin, Professor of Biology and of Plant and Soil Sciences Lexington, Kentucky 2008 Copyright © Gehan Jayasuriya 2008 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION COMPARATIVE BIOLOGY OF SEED DORMANCY-BREAK AND GERMINATION IN CONVOLVULACEAE (ASTERIDS, SOLANALES) The biology of seed dormancy and germination of 46 species representing 11 of the 12 tribes in Convolvulaceae were compared in laboratory (mostly), field and greenhouse experiments. -

The Carnivora of Madagascar

THE CARNIVORA OF MADAGASCAR 49 R. ALBIGNAC The Carizizrorn of Madagascar The carnivora of Madagascar are divided into 8 genera, 3 subfamilies and just one family, that of the Viverridae. All are peculiar to Madagascar except for the genus Viverricula, which is represented by a single species, Viverricula rasse (HORSFIELD),which is also found throughout southern Asia and was probably introduced to the island with man. Palaeontology shows that this fauna is an ancient one comprising many forms, which appear to be mainly of European origin but with very occasional kinships with the Indian region. For instance, Cvptofiroctaferox, although perhaps not directly related to Proailurus lenianensis (a species found in the phosphorites of the Quercy region of France and in the Aquitanian formations of Saint Gérand-le- Puy) , nevertheless appears to be the descendant of this line. Similarly, the origin of the Fossa and Galidiinae lines would seem to be close to that of the holarctic region. Only Eupleres raises a problem, having affinities with Chrotogale, known at present in Indochina. The likely springboard for these northern species is the continent of Africa. This archaic fauna has survived because of the conservative influence of the island, which has preserved it into modern times. In the classification of mammals G. G. SIMPSONputs the 7 genera of Madagascan carnivora in the Viverridae family and divides them into 3 subfamilies, as shown in the following table : VIVERRIDAE FAMILY Fossinae subfamily (Peculiar to Madagascar) Fossa fossa (Schreber) Eupleres goudotii Doyère Galidiinae subfamily (peculiar to Madagascar) Galidia elegans Is. Geoffroy Calidictis striata E. Geoffroy Mungotictis lineatus Pocock Salanoia concolor (I. -

A Dissertation Submitted to T

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE BET-HEDGING IN HETEROCARPIC GRINDELIA CILIATA (ASTERACEAE) A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By MICHAEL KISTENMACHER Norman, Oklahoma 2017 BET-HEDGING IN HETEROCARPIC GRINDELIA CILIATA (ASTERACEAE) A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF MICROBIOLOGY AND PLANT BIOLOGY BY ______________________________ Dr. J. Phil Gibson, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Bruce Hoagland ______________________________ Dr. Heather McCarthy ______________________________ Dr. Abigail Moore ______________________________ Dr. Lara Souza © Copyright by MICHAEL KISTENMACHER 2017 All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements I wish to thank Dr. J. Phil Gibson and Dr. Gordon Uno for seeing potential in me and for making the transition into graduate school possible. I also wish to thank Dr. J. Phil Gibson for mentoring me through this dissertation, which I imagine took a lot of patience and understanding. I thank all of my committee members for helping me develop my knowledge and projects. A special thanks to the faculty of the University of Oklahoma Department of Microbiology and Plant Biology for guiding me towards understanding all aspects of plant biology, from the subcellular to ecosystems. A very special thank you to my parents, Monika and Hans, for your never ending support and love. Thank you to my brothers, Martin and Peter, for sharing your experiences and insight of college and life. The completion of this dissertation -

Fragrant Annuals Fragrant Annuals

TheThe AmericanAmerican GARDENERGARDENER® TheThe MagazineMagazine ofof thethe AAmericanmerican HorticulturalHorticultural SocietySociety JanuaryJanuary // FebruaryFebruary 20112011 New Plants for 2011 Unusual Trees with Garden Potential The AHS’s River Farm: A Center of Horticulture Fragrant Annuals Legacies assume many forms hether making estate plans, considering W year-end giving, honoring a loved one or planting a tree, the legacies of tomorrow are created today. Please remember the American Horticultural Society when making your estate and charitable giving plans. Together we can leave a legacy of a greener, healthier, more beautiful America. For more information on including the AHS in your estate planning and charitable giving, or to make a gift to honor or remember a loved one, please contact Courtney Capstack at (703) 768-5700 ext. 127. Making America a Nation of Gardeners, a Land of Gardens contents Volume 90, Number 1 . January / February 2011 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS 5 NOTES FROM RIVER FARM 6 MEMBERS’ FORUM 8 NEWS FROM THE AHS 2011 Seed Exchange catalog online for AHS members, new AHS Travel Study Program destinations, AHS forms partnership with Northeast garden symposium, registration open for 10th annual America in Bloom Contest, 2011 EPCOT International Flower & Garden Festival, Colonial Williamsburg Garden Symposium, TGOA-MGCA garden photography competition opens. 40 GARDEN SOLUTIONS Plant expert Scott Aker offers a holistic approach to solving common problems. 42 HOMEGROWN HARVEST page 28 Easy-to-grow parsley. 44 GARDENER’S NOTEBOOK Enlightened ways to NEW PLANTS FOR 2011 BY JANE BERGER 12 control powdery mildew, Edible, compact, upright, and colorful are the themes of this beating bugs with plant year’s new plant introductions. -

Which Morningglory Do I Have?

Which Morningglory Do I Have? With the adoption of herbicide resistant crops in today’s crop production systems, weed population shifts can and do occur. In particular, fields where crops resistance to glyphosate are grown in a continuous or semi-continuous basis, morningglory populations will increase due to the tolerance of this species to glyphosate (Roundup and other names). This, of course leads to the question of ‘Which morningglory do I have in my field?’ In North Carolina, we have many morningglory species. Generally, four species occur most frequently. These are ivyleaf, entireleaf, tall, and pitted. SCIENTIFIC NAMES: Ivyleaf Morningglory (Ipomoea hederacea) Entirelaef Morningglory (Ipomoea hederacea var. integriuscula). Tall Morningglory (Ipomoea purpurea) Pitted Morningglory (Ipomoea lacunosa) COTYLEDON SHAPE AND CONFIGURATION: Of course, the earlier a weed is identified, the better chance a grower has of controlling it. So the first feature to try to identify morningglories is the cotyledon. If a grower knows what the weed is before the first true leaf appears, he/she has the upper hand. Most morningglories have cotyledons that are shaped like butterfly wings. The shape and configuration of these "wings" will help separate the species. Ivy/Entire. As you can see by the scientific names above, ivyleaf and entireleaf morningglory are very similar. In fact, when you look at the cotyledon, you can not distinguish between the two. The butterfly wings on the cotyledons of both of these have rounded tips and the angle of the wings is <90 degrees. The outer edges of the wings are not parallel with one another. This is sometimes referred to as an "open butterfly" cotyledon.