The Role of Store-Image and Functional Image Congruity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Focusing on the Street Quarter of Mapo-Ro in Seoul Young-Jin

Urbanities, Vol. 8 · No 2· November 2018 © 2018 Urbanities High-rise Buildings and Social Inequality: Focusing on the Street Quarter of Mapo-ro in Seoul Young-Jin Kim (Sungshin University, South Korea) [email protected] In this article I discuss the cause and the effects of the increase in high-rise buildings in the ‘street quarter’ of Mapo-ro in Seoul, South Korea. First, I draw on official reports and Seoul Downtown Redevelopment Master Plans to explore why this phenomenon has occurred. Second, I investigate the sociocultural effects of high-rise buildings using evidence collected through an application of participant observation, that is, a new walking method for the study of urban street spaces. I suggest that the Seoul government’s implementation of deregulation and benefits for developers to facilitate redevelopment in downtown Seoul has resulted in the increase of high-rise buildings. The analysis also demonstrates that this increase has contributed to gentrification and has led to the growth of private gated spaces and of the distance between private and public spaces. Key words: High-rise buildings, residential and commercial buildings, walking, Seoul, Mapo-ro, state-led gentrification. Introduction1 First, I wish to say how this study began. In the spring of 2017, a candlelight rally was held every weekend in Gwanghwamun square in Seoul to demand the impeachment of the President of South Korea. On 17th February, a parade was added to the candlelight rally. That day I took photographs of the march and, as the march was going through Mapo-ro,2 I was presented with an amazing landscape filled with high-rise buildings. -

Interpretation of Social Media Identity in the Era of Contemporary Globalization

Interpretation of Social Media Identity in the Era of Contemporary Globalization By Laila Hyo-Sun Shin Rohani A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Management Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Laila Rohani, December, 2015 ABSTRACT INTERPRETATION OF SOCIAL MEDIA IDENTITY IN THE ERA OF CONTEMPORARY GLOBALIZATION Laila Rohani Advisor: University of Guelph, 2015 Dr. May Aung The new reality of contemporary globalization and its impact on consumers is an on-going interest to scholars from many disciplines. This study is positioned to take the understanding of this new reality to the context of social media consumers. The primary objective of this research is to explore how consumers create and portray their social media identities in the era of contemporary globalization by reflecting the global social media context as well as their own social and cultural backgrounds. In order to achieve the research objective, this study embraced the globalization conceptual background and the concept of self/others. Specifically, this research explores the social media consumption behaviour (the creation of self and others) of two groups of Facebook (FB) consumers, Canadian FB consumers and Korean FB consumers. Three sub-sets of FB consumption culture: personal identity building culture, social networking culture, and brand engagement culture relevant to Facebook consumption context are examined. This study involves three stages, starting with the preliminary examination of Facebook attributes using quantitative approach. The second stage involves participant observation and content analysis of 100 FB profile pages. The last stage involves in-depth interviews of Canadian and Korean FB users. -

How Will the Economic Policies of South Korea's New Administration

How will the Economic Policies of South Korea’s New Administration Influence Economic Relations with Japan? By Hidehiko Mukoyama Senior Economist Economics Department Japan Research Institute Summary 1. The presidential election held in South Korea in December 2012 was essentially a two-horse race between Park Geun-hye of the incumbent conservative Saenuri Party and Moon Jae-in from the progressive Democratic United Party, which was in opposition. A feature of the election that attracted intense interest was the fact that both candidates called for economic democratization and the enhancement of the welfare system because of their concern about the failure of the traditional pattern of growth led by the chaebol groups to contribute sufficiently to the improvement of living standards in South Korea. 2. Characteristics of the South Korean growth model that evolved during the first decade of the 21st century include global business expansion led by the chaebol groups, active government support for big business, and export-led growth. How- ever, while exports have been a growth driver, there have also been issues, such as employment problems and job insecurity for young people, and widening income disparity. In addition, deregulatory measures carried out by the Lee Myung-bak ad- ministration have had the effect of concentrating economic power in the hands of the chaebol, while small and medium enterprises have come under pressure from the ex- panding business activities of the chaebol. 3. Mr. Moon stated that he wanted to resurrect the equity investment ceiling system, which was abolished by the Lee Myung-bak administration, and announced a policy calling for the dissolution of cyclical investments within three years. -

The Tastes of Bomun Lake Resort Dining Guide for Visitors Bomun Lake Complex Within 3.5Km of HICO, One-Way Taxi Fare Under KRW 5,000

Dining Guide for Visitors for Guide Dining Bomun Lake Resort Lake Bomun The Tastes of Tastes The Bobul-ro within 8km of HICO, one-way taxi fare under KRW 10,000 Hollys Coffee Sandre 1 Coffee N’ Crema 2 Jeongsugaseong Cafe Numaru Hadong Reservoir Namcheon Stream Silla Arts and Science Museum Gunglim Kalguksu 3 Ssukbujaengi Gyeongju Folk Craft Village 4 Bobul-ro Lane Sotheby Coffee GS 25 Convenience Store HICO Bulguksa Temple 5 Cafe Road 100 Cafe Buyeon 6 Gosaekchangyeon 10, 11, 18, 100, 100-1, 150, 150-1 Angel-in-us Coffee Cafe Dalkongs 7 Yusujeong Ssambap Bobul-ro 8 Byeoldang Hanjeongsik Restaurant 1 Sandre (산드레) 2 Jeongsugaseong (정수가성) 3 Gunglim Kalguksu (궁림칼국수) 4 Ssukbujaengi (쑥부쟁이) Menu Traditional Korean meal Menu Tteokgalbi (minced shortribs) Menu Noodles with clams Menu Lotus leaf rice wraps Address 299-5, Bobul-ro (보불로 299-5) Address 318, Bobul-ro (보불로 318) Address 193, Saegol-gil (새골길 193) Address 147-5, Bobul-ro (보불로 147-5) Time 11:00-21:000 Time 09:00-21:30 Time 10:30~21:00 Time 11:30-21:00 Tel +82-(0)54-746-5400 Tel +82-(0)54-745-0066 Tel +82-(0)54-748-1049 Tel +82-(0)54-748-3903 Price KRW 15,000 Price KRW 10,000 Price KRW 6,000 Price KRW 15,000 5 Cafe Road 100 (카페 로드백) 6 Gosaekchangyeon (고색창연) 7 Yusujeong Ssambap (유수정쌈밥) 8 Byeoldang Hanjeongsik (별당한정식) Menu Brunch Menu Tteokgalbi (minced short ribs) Menu Bulgogi ssambap (rice wraps with beef) Menu Traditional Korean meal Address 100, Bobul-ro (보불로 100) Address 58-4, Bobul-ro (보불로 58-4) Address 26, Bobul-ro (보불로 26) Address 19, Madongtammaeul-gil (마동탑마을길 19) Time 10:00~22:30 -

ENCORP PACIFIC (CANADA) Registered Brands

ENCORP PACIFIC (CANADA) Registered Brands 1 7 10 Cal Aquafina Plus Vitamins 7 select 10 YEARS OIL PATCH TOUGH LONGHORN 7 Select Café 100 Plus 7 UP 100PLUS 7 up Lemon 1181 7-Select 1818 Alberni 7-SELECT 7-Up 2 7-Up 2 Guys With Knives 7D Mango Nectar 2% 7SELECT 24 Hour Collision Center 7Select 24 Mantra Mango Juice 7SELECT Natural Spring Water 24K 7UP 27 North 7up 28 Black 7up Lemon Lemon Sparkling Lemonade 3 8 3 The Terraces Three 80 Degrees 33 Acres Of Heart 80 Degrees North 33 Acres of Mineral 33 Acres of Pacific 9 33 Acres of Sunrise 9 MM Energy Drink 365 A 365 Everyday Value A & W 365 Organic Lemonade A (Futura) 365 Organic Limeade A&W 365 Whole Foods Market A&W Apple Juice 4 A&W Orange Juice 49th Parallel Cascara A-Team Mortgages 49th Parallel Cold Brew A2Z Capital 49th Parallel Grocery Abbott Wealth Management 49th Parallel Iced Tea Aberfoyle Springs 49th Parallel Sparkling Green Tea Abhishek Mehta-MarforiGroup, Mr Home Inspector ABK Restoration Services 5 Abstract Creating Iconic Spaces 5 Hour Energy Abstract Developments 5 Hour Energy Acapulcoco 5 Hour Energy Extra Strength Accelerade 5-hour Energy Extra Strength Access Roadside Assistance 5-HOUR EXTRA STRENGTH Accompass 52 North Beverages Acme Analytical Laboratories Ltd. 52° North Acqua Di Aritzia 59th Street Food Co. Acqua Filette 6 Acqua Italia 6 Hour Power Acqua Panna 601 West Hastings ACTIVATE BALANCE - Fruit Punch ACTIVATE BEAUTY - Exotic Berry ACTIVATE CHARGED - Lemon Lime Wednesday, September 01, 2021 The General Identification Guidelines should be read along with this brand registry listing. -

Pub. No.: US 2011/0260440 A1 HAFF Et Al

US 20110260440A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2011/0260440 A1 HAFF et al. (43) Pub. Date: Oct. 27, 2011 (54) DISPOSABLE CUP WITH INTERNAL AND (52) U.S. Cl. ........................................ 283/67; 206/459.1 EXTERNAL FLUID LEVEL INDICATORS AND METHOD (57) ABSTRACT A method for using an associated visual implementing appa (76) Inventors: Maurice HAFF, Bethesda, MD ratus with which a first person may audibly or otherwise (US); John M. White, Bethesda, specify, e.g., a head nod, to a second person the amount of MD (US) unoccupied volume or void to be available in an illustrated cup when partially filled with coffee or other liquid, in (21) Appl. No.: 12/955,409 response to an easily understood inquiry by the second per son. The method includes the steps of a first person exhibiting (22) Filed: Nov. 29, 2010 the illustrated cup to a second person while inquiring as to the unoccupied Volume desired to remain while making refer Related U.S. Application Data ence to the illustrated cup. The visual implementing appara (60) Provisional application No. 61/327,887, filed on Apr. tus cup includes repeating vertically oriented illustrations, the 26, 2010. illustrations being at least one of representations of human fingers, cows, text based words describing cow Sounds, num bers, geographic shapes, logos, and/or indentations. The Publication Classification repeating illustrations being representative of the relative (51) Int. C. remaining proportional Void levels in the cup and residing on B42D IS/00 (2006.01) at least one of the exterior and/or the interior of the cup near B65D 85/00 (2006.01) the rim thereof. -

Café Especial Del Mercado De Corea Del Sur

ÍNDICE COREA DEL SUR 1 Perfil de Café Especial del mercado de Corea del Sur el Sur a d - Co re ducto re o Pro - P a C e e d - d rf e r i l il l u S f d S r u e e l r P e P - d r C o - o a d e r o u r e t c a o c t u o C d d - - e o P r r l e P r e u f S i l d S u l r e - d C o a e r Ministerio de Comercio Exterior y Turismo 2 Perfil de Producto:CAFÉ ESPECIAL “Este perfil de producto ha sido elaborado en el mercado coreano, utilizando fuentes primarias y secundarias. El trabajo realizado ha sido supervisado y validado por la OCEX Seúl, y ha contado con la colaboración de la Dirección de Desarrollo de Mercados Internacionales del MINCETUR y de PROMPERÚ. Se autoriza la reproducción de la información contenida en este documento siempre y cuando se mencione la fuente: “MINCETUR. Plan de Desarrollo de Mercado de Corea del Sur” ÍNDICE COREA DEL SUR 3 4 Perfil de Producto:CAFÉ ESPECIAL Índice Introducción 6 1. Tamaño del Mercado 8 1.1 Tamaño del mercado del café terminado 10 1.2 Tamaño del mercado por franquicias 13 1.3 Producción local 16 1.4 Exportaciones del país de destino 17 1.5 Importaciones del país destino y análisis de los principales competidores 17 2. Análisis de la Demanda 22 2.1 Usos y formas de consumo 22 2.2 Análisis de tendencias 23 2.3 Atributos y percepción del producto peruano 25 3. -

ECCK Connect

Autumn 2016 Social Responsibility ECCK Connect Médicins Sans Frontières (MSF) Page 20 The Quarterly Green Drinks Seoul Page 22 Government Project Korean Free Economic Zones Page 24 Magazine of the EU Presidency - Slovakia Page 26 European Chamber of Cover Story Interview with Gerard Consulting Page 30 Commerce in Korea spiritsEUROPE Page 34 Cover Story Food & Beverage Market in Korea Page 28 2 President’s Message Dear Readers, Welcome to the Autumn 2016 edition of ECCK Connect. I hope you had a wonderful summer vacation, and are enjoy- ing the start of beautiful autumn weather in Korea. The beginning of autumn was highlighted with the ECCK Breakfast Seminar with Director of the Cartels Directorate, DG Competition of the European Commission, which discussed on the topic of ‘latest trends in EU Cartel Policy’. The ECCK was pleased to have organized the meeting, and we will conti- nue to effectively function as the representative of members’ voices at a policy level. Meanwhile, the ECCK has held several information sessions and seminars on Compliance, IP Capaci- ty building, and CFO Forum, while launching the ECCK Acade- my which provides training courses for employees of European companies operating in Korea. As we are gearing up for the upcoming events in the following months, ECCK Connect has prepared articles about Korea’s industry landscape in more detail. This edition covers the food and beverages market, for the industry has seen interesting changes lately interacting with foreign influence. With the support of the ECCK, a worldwide networking event for people who work for and interested in the environmental field known as Green Drinks, is finally launching in Seoul. -

BDO Preferred Merchants P150 OFF on Grabfood with BDO Mastercard November 16 to December 15, 2020 Total No. of Merchants: 1,699

BDO Preferred Merchants P150 OFF on GrabFood with BDO Mastercard November 16 to December 15, 2020 Total No. of Merchants: 1,699 A. Top Merchants (Count: 39) 7 24 Chicken 1 Botejyu 8 24/7 Burser 2 Buffalo Wild Winss 9 24/7 Milk Tea 3 California Pizza Kitchen 10 24/7 Party Trays 4 Chilis 11 24/7 Rice Bowls 5 Cibo 12 24/7 Super Chicken 6 Classic Savory 13 24/7 Super Healthy 7 Dencio's 14 24/7 Winss 8 Din Tai Funs 15 250 Cafe 9 FRNK Milk Bar 16 28 Treasure 10 Gerry's Grill Restaurant & Bar 17 390 Desrees 11 Gloria Maris Shark's Fin Restaurant 18 3M Pizza 12 Hap Chan 19 4k's Homemade Specialtes 13 J Co 20 7997 Brown Mandarin Asian Streetood 14 Jamba Juice 21 8Cuts 15 Joybean 22 8t5 Milk Tea Staton 16 Kimono Ken 23 90 Tea's Boba Tea Cafe 17 Kins Chef 24 A Veneto Pizzeria Ristorante 18 Kuya J 25 A'Toda Madre 19 La Chinesca at The Grid 26 A+ Premium Milk Tea 20 Lola Café 27 Ababu Persian Kitchen 21 Lusans 28 Abe 22 Macao Imperial Tea 29 About Tea by Cha Tuk Chak 23 Mama Lou's 30 Above Sea Level 24 Manam 31 Adobo Connecton 25 Mann Hann 32 Adobowls 26 Max's Restaurant 33 Adriano's Resto Bar 27 Mo' Cookies 34 Afters Espresso & Desserts 28 Pancake House 35 Asave 29 Pepper Lunch 36 Asico Vesetarian Cafe 30 Seatle's Best Coffee 37 Ah Mah 31 Shi Lin 38 Al Jabrez Halal Restaurant 32 Sizzlin' Steak 39 Al Josrats 33 Soban K-Town 40 Alas Pares Maceda 34 Starbucks 41 Alba Restaurante Espanol 35 Teriyaki Boy 42 Alcoline.ph 36 Tim Ho Wan 43 Alejandro`s Roasted Chicken 37 Tim Horton's 44 Alins Banans's 38 Tons Yans 45 Alins Tonans's Pancit Palabok 39 Wild Flour 46 Alipapa Cafe 47 Alishan at the Alley 48 All The Winss of Love 49 All You Need Diner B. -

Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper Mckinley Rd. Mckinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel

Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper McKinley Rd. McKinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel. No. 238-6300 Website: http://www.ipophil.gov.ph e-mail: [email protected] Publication Date: February 23, 2015 1 ALLOWED MARKS PUBLISHED FOR OPPOSITION ............................................................................................... 2 1.1 ALLOWED NATIONAL MARKS ....................................................................................................................................... 2 Intellectual Property Center, 28 Upper McKinley Rd. McKinley Hill Town Center, Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City 1634, Philippines Tel. No. 238-6300 Website: http://www.ipophil.gov.ph e-mail: [email protected] Publication Date: February 23, 2015 1 ALLOWED MARKS PUBLISHED FOR OPPOSITION 1.1 Allowed national marks Application No. Filing Date Mark Applicant Nice class(es) Number 29 June 1 4/2011/00007637 HOLLYS COFFEE HOLLYS F&B CO., LTD. [KR] 43 2011 6 2 4/2011/00014525 December ERGODYNAMIC OMESH VASWANI [PH] 20 2011 NORTHERN GLOBAL 2 August 3 4/2012/00009536 CONSUMER FOOD 29 and 30 2012 SOLUTIONS, INC. [PH] 3 August SANTINOS SUPER PIZZA PEDERICO`S FOOD 4 4/2012/00009594 30 2012 SLICE! CORPORATION [PH] BLAINE PERSONAL BLAINE PERSONAL AND 6 August 5 4/2012/00009706 AND HOME CARE HOME CARE 1; 3; 35 and 44 2012 CORPORATION CORPORATION [PH] REFAMED RESEARCH 6 August 6 4/2012/00009707 REFAMED LABORATORY 1; 5; 31; 35 and 44 2012 CORPORATION [PH] REFAMED RESEARCH 6 August 7 4/2012/00009708 REFAMED LABORATORY 1; 5; 31; 35 and 44 2012 CORPORATION [PH] 19 October 8 4/2012/00012869 KING DRAGON DEXTER C. CHIONG [PH] 7 2012 25 June LABORATOIRES D`ANJOU 9 4/2012/00501609 CEBELIA 3 2012 [FR] 20 July MICROSOFT CORPORATION 10 4/2012/00501872 9; 38 and 42 2012 [US] 29 May CATHERINE ISRAEL 11 4/2013/00006114 SPARKLES 16; 28 and 41 2013 ANGELES [PH] 18 July FURUTEC ELECTRICAL SDN 12 4/2013/00008553 FURUTEC 9 2013 BHD [MY] INJOY ICE 12 August SCRAMBLE DOXO INGREDIENTS INC. -

The Effect of the Corporate Social Responsibility of Franchise Coffee

sustainability Article The Effect of the Corporate Social Responsibility of Franchise Coffee Shops on Corporate Image and Behavioral Intention Jae-Bin Cha 1 and Mi-Na Jo 2,* 1 Department of Public Health Administration, Kyungmin University, Euijeongbu 11618, Korea; [email protected] 2 Division of Hotel & Tourism, The University of Suwon, Suwon 18323, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-31-229-8308 Received: 27 October 2019; Accepted: 22 November 2019; Published: 2 December 2019 Abstract: This study investigated the effects of the corporate social responsibility (CSR) of franchise coffee shops on their corporate image and their customers’ behavioral intention. From 5 October 2017 to 26 October 2017, a total of 300 survey questionnaires were distributed, out of which 285 were analyzed. Accordingly, among the dimensions of CSR, only the economic, discretionary, and legal responsibilities had significant effects on corporate image. Moreover, corporate image had a significant effect on customers’ behavioral intention. Therefore, the CSR of franchise coffee shops is an important antecedent of corporate image, while corporate image is an important antecedent of behavioral intention. With respect to the pyramid of CSR, economic responsibilities should be first fulfilled prior to other social responsibilities. In addition, CSR programs will become the core task of corporate sustainable management because CSR can potentially influence consumers to have a positive behavioral intention and can result in product preferences by conveying a particular corporate image. Keywords: CSR; corporate image; behavioral intention 1. Introduction Despite the global economic recession, the coffee industry in Korea has witnessed continued growth in the last decade. Korea Customs Service reported that one adult consumes 512 cups of coffee a year in 2017, thus indicating coffee is consumed more often than kimchi or rice. -

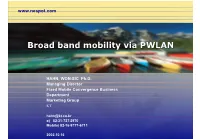

Broad Band Mobility Via PWLAN

www.nespot.com Broad band mobility via PWLAN HAHN, WON-SIC Ph.D. Managing Director Fixed Mobile Convergence Business Department Marketing Group KT [email protected] o) 82-31-727-2970 Mobile) 82-16-9777-6711 2002.10.16 OverviewOverview Part I. Market Push Part II. Motivation of PWLAN Part III. NESPOT, PWLAN Service in KOREA www.nespot.com Part I. Market Push Broadband Global Market Share 60 53.54 50 40 Market Share 30 15.66 20 14.49 7.81 10 5.79 2.71 0 etc USA Korea Japan China Germany 2002 Broadband Market Share in Korea 60 50 48.99 40 Market Share 30 27.13 20 16.57 10 7.32 0 KT Hanaro Thruet etc Broadband Extension for Hidden Market in KOREA (I) Speed /Users 10M (Sep. 2002) Hidden Market 8Mbps Broad band WLAN 31M(2001.12) 2Mbps CDMA Mobility Stationary Quasi- Mobile Broad band WLAN CDMA Coverage Home, Office Hot spots + Home + Office Wide area Throughput high high Low Terminals PC PDA, Notebook,Desk top Phone, PDA Applications WEB E-book, VOD, AOD, mp3 Voice, POP3 Mail, Messenger Short Message Customers Students at home Students/businessmen at home, Ordinary users campus and office Internet power users in hotspot area Promoted PC, DSL, Router, PDA, Wireless-LAN, Notebook CDMA, Phone Industry Portal Industry Broadband Extension for Hidden Market in KOREA (II) Unit:1,000 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 Broadband Subscribers Expected 9,536 10,691 11,574 11,928 12,167 Net Addition 1,691 1,155 884 354 239 Wireless LAN + BB Users Expected 191 1,829 3,089 3,632 4,068 Subscription Ratio out of Broadband sub.(%) 2.0% 17.1% 26.7% 30.4% 33.4% 14000 12000 10000 8000 6000 4000 2000 0 2002E 2003F 2004F 2005F 2006F Source : LG Investment & security.