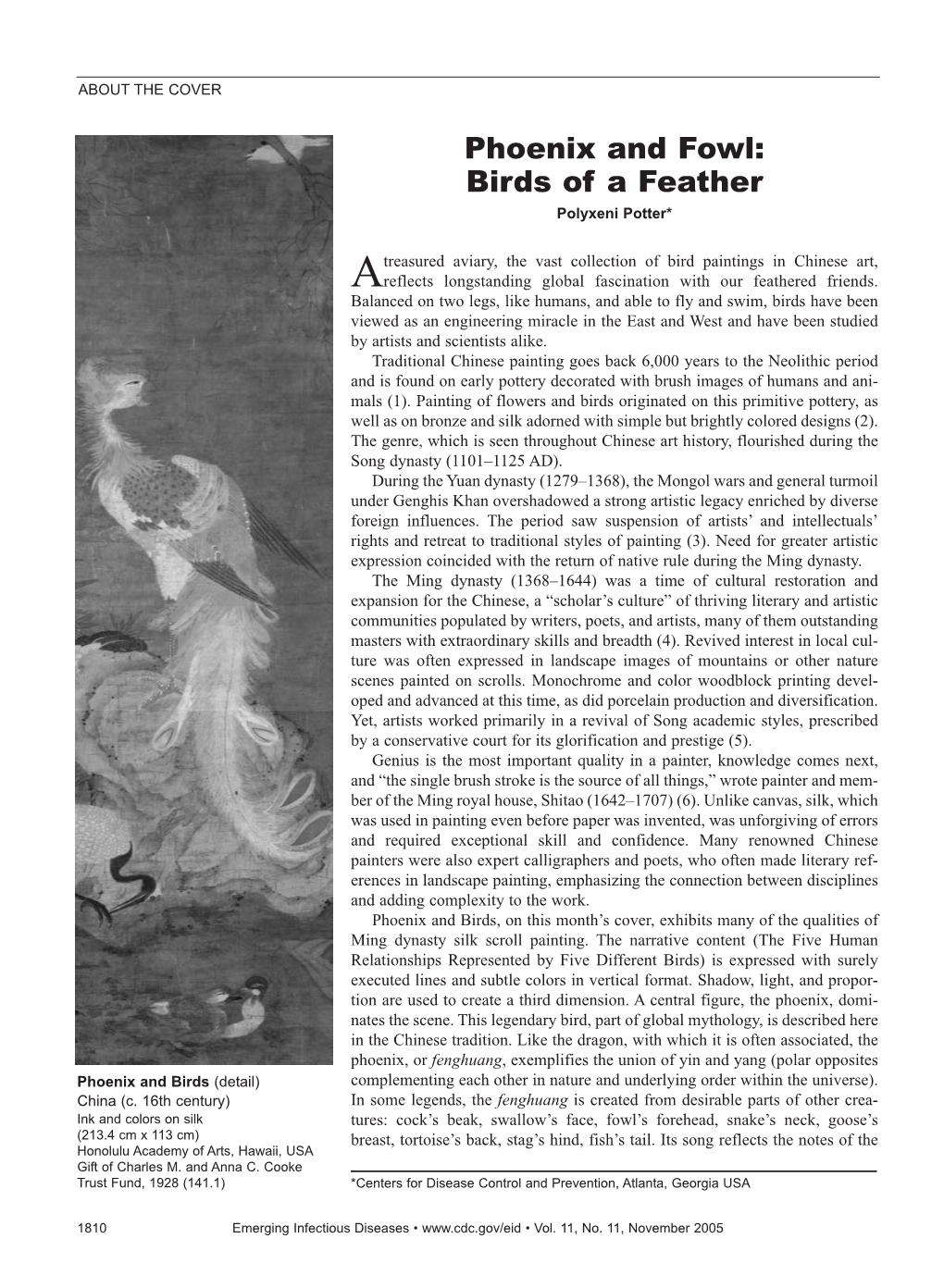

Phoenix and Fowl: Birds of a Feather Polyxeni Potter*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Iranian Therapist and Her Cambodian Clients

11/11/2018 cerieastbay.org/web3/media/dragon.html excerpt from UNDER THE DRAGON California's New Culture by Lonny Shavelson and Fred Setterberg buy the book T h e I r a n i a n T h e r a p i s t a n d H e r C a m b o d i a n C l i e n t s by Lonny Shavelson and Fred Setterberg Dr. Mona Afari studied Lay’s impassive expression as the translator rendered his words from Cambodian into English. “My mother and father,” she heard the translator repeat, “…the Khmer Rouge take them. I never see again.” Mona watched Lay’s eyes spark with pain as he recounted the story of his parents’ murder, and she asked herself the question that had haunted her since founding the weekly therapy group: Could she— an Iranianborn, female therapist—breach the chasm separating her from these six middleaged male survivors of the Cambodian holocaust and provide the help they desperately needed? The Cambodian men had spilled into Oakland’s largely Latino Fruitvale District like victims thrown from a terrible traffic accident—uneducated villagers battered physically and psychologically, utterly unprepared for life in America. In stark contrast, Mona was the upper class daughter of an Iranian industrialist, an educated urban cosmopolite, a Jew from a Muslim nation, and a willing immigrant to the United States. Mona concentrated on the tone of Lay’s voice. She did not understand the Cambodian language, but neither was she completely comfortable in English. -

Zodiac Animal Masks

LUNAR NEW YEAR ZODIAC ANIMAL MASKS INTRODUCTION ESTIMATED TIME The Year of the Ox falls on February 12 this year. 15–20 minutes The festival is celebrated in East Asia and Southeast Asia and is also known as Chun Jié (traditional Chinese: 春節; simplified Chinese:春节 ), or the Spring MATERIALS NEEDED Festival, as it marks the arrival of the season on the lunisolar calendar. • Chart (on the next page) to find your birth year and corresponding zodiac animal The Chinese Zodiac, known as 生肖, is based on a • Zodiac animal mask templates twelve-year cycle. Each year in that cycle is correlated to an animal sign. These signs are the rat, ox, tiger, • Printer rabbit, dragon, snake, horse, goat, monkey, rooster, dog, • Colored pencils, markers, crayons, and/or pens and pig. It is calculated according to the Chinese Lunar • Scissors calendar. It is believed that a person’s zodiac animal offers insights about their personality, and the events • Hole punch in his or her life may be correlated to the supposed • String influence of the person’s particular position in the twelve-year zodiac cycle. Use the directions below to teach your little ones STEPS how to create their own paper zodiac animal mask to 1. Using the Chinese zodiac chart on the next page, celebrate the Year of the Ox! find your birth year and correlating zodiac animal. 2. Print out the mask template of your zodiac animal. 3. Color your mask, cut it out, and use a hole punch and string to make it wearable. CHINESE ZODIAC CHART LUNAR NEW YEAR CHINESE ZODIAC YEAR OF THE RAT YEAR OF THE OX YEAR OF THE TIGER 1972 • 1984 • 1996 • 2008 1973 • 1985 • 1997 • 2009 1974 • 1986 • 1998 • 2010 Rat people are very popular. -

Towards a Christian Pastoral Approach to Cambodian Culture

Thesis Title: Towards a Christian Pastoral Approach to Cambodian Culture In fulfilment of the requirements of Master’s in Theology (Missiology) Submitted by: Gerard G. Ravasco Supervised by: Dr. Bill Domeris, Ph D March, 2004 Towards a Christian Pastoral Approach to Cambodian Culture Table of Contents Page Chapter 1 1.0 Introduction 1 1.1 The world we live in 1 1.2 The particular world we live in 1 1.3 Our target location: Cambodia 2 1.4 Our Particular Challenge: Cambodian Culture 2 1.5 An Invitation to Inculturation 3 1.6 My Personal Context 4 1.6.1 My Objectives 4 1.6.2 My Limitations 5 1.6.3 My Methodology 5 Chapter 2 2.0 Religious Influences in Early Cambodian History 6 2.1 The Beginnings of a People 6 2.2 Early Cambodian Kingdoms 7 2.3 Funan 8 2.4 Zhen-la 10 2.5 The Founding of Angkor 12 2.6 Angkorean Kingship 15 2.7 Theravada Buddhism and the Post Angkorean Crisis 18 2.8 An Overview of Christianity 19 2.9 Conclusion 20 Chapter 3 3.0 Religions that influenced Cambodian Culture 22 3.1 Animism 22 3.1.1 Animism as a Philosophical Theory 22 3.1.2 Animism as an Anthropological Theory 23 3.1.2.1 Tylor’s Theory 23 3.1.2.2 Counter Theories 24 3.1.2.3 An Animistic World View 24 3.1.2.4 Ancestor Veneration 25 3.1.2.5 Shamanism 26 3.1.3 Animism in Cambodian Culture 27 3.1.3.1 Spirits reside with us 27 3.1.3.2 Spirits intervene in daily life 28 3.1.3.3 Spirit’s power outside Cambodia 29 3.2 Brahmanism 30 3.2.1 Brahmanism and Hinduism 30 3.2.2 Brahmin Texts 31 3.2.3 Early Brahmanism or Vedism 32 3.2.4 Popular Brahmanism 33 3.2.5 Pantheistic Brahmanism -

Tier 1 Manufacturing Sites

TIER 1 MANUFACTURING SITES - Produced January 2021 SUPPLIER NAME MANUFACTURING SITE NAME ADDRESS PRODUCT TYPE No of EMPLOYEES Albania Calzaturificio Maritan Spa George & Alex 4 Street Of Shijak Durres Apparel 100 - 500 Calzificio Eire Srl Italstyle Shpk Kombinati Tekstileve 5000 Berat Apparel 100 - 500 Extreme Sa Extreme Korca Bul 6 Deshmoret L7Nr 1 Korce Apparel 100 - 500 Bangladesh Acs Textiles (Bangladesh) Ltd Acs Textiles & Towel (Bangladesh) Tetlabo Ward 3 Parabo Narayangonj Rupgonj 1460 Home 1000 - PLUS Akh Eco Apparels Ltd Akh Eco Apparels Ltd 495 Balitha Shah Belishwer Dhamrai Dhaka 1800 Apparel 1000 - PLUS Albion Apparel Group Ltd Thianis Apparels Ltd Unit Fs Fb3 Road No2 Cepz Chittagong Apparel 1000 - PLUS Asmara International Ltd Artistic Design Ltd 232 233 Narasinghpur Savar Dhaka Ashulia Apparel 1000 - PLUS Asmara International Ltd Hameem - Creative Wash (Laundry) Nishat Nagar Tongi Gazipur Apparel 1000 - PLUS Aykroyd & Sons Ltd Taqwa Fabrics Ltd Kewa Boherarchala Gila Beradeed Sreepur Gazipur Apparel 500 - 1000 Bespoke By Ges Unip Lda Panasia Clothing Ltd Aziz Chowdhury Complex 2 Vogra Joydebpur Gazipur Apparel 1000 - PLUS Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Amantex Limited Boiragirchala Sreepur Gazipur Apparel 1000 - PLUS Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Asrotex Ltd Betjuri Naun Bazar Sreepur Gazipur Apparel 500 - 1000 Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Metro Knitting & Dyeing Mills Ltd (Factory-02) Charabag Ashulia Savar Dhaka Apparel 1000 - PLUS Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Tanzila Textile Ltd Baroipara Ashulia Savar Dhaka Apparel 1000 - PLUS Bm Fashions (Uk) Ltd Taqwa -

Daily Life for the Common People of China, 1850 to 1950

Daily Life for the Common People of China, 1850 to 1950 Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access China Studies published for the institute for chinese studies, university of oxford Edited by Micah Muscolino (University of Oxford) volume 39 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/chs Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access Daily Life for the Common People of China, 1850 to 1950 Understanding Chaoben Culture By Ronald Suleski leiden | boston Ronald Suleski - 978-90-04-36103-4 Downloaded from Brill.com04/05/2019 09:12:12AM via free access This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing cc-by-nc License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. Cover Image: Chaoben Covers. Photo by author. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Suleski, Ronald Stanley, author. Title: Daily life for the common people of China, 1850 to 1950 : understanding Chaoben culture / By Ronald Suleski. -

Records of the Transmission of the Lamp (Jingde Chuadeng

The Hokun Trust is pleased to support the fifth volume of a complete translation of this classic of Chan (Zen) Buddhism by Randolph S. Whitfield. The Records of the Transmission of the Lamp is a religious classic of the first importance for the practice and study of Zen which it is hoped will appeal both to students of Buddhism and to a wider public interested in religion as a whole. Contents Foreword by Albert Welter Preface Acknowledgements Introduction Appendix to the Introduction Abbreviations Book Eighteen Book Nineteen Book Twenty Book Twenty-one Finding List Bibliography Index Foreword The translation of the Jingde chuandeng lu (Jingde era Record of the Transmission of the Lamp) is a major accomplishment. Many have reveled in the wonders of this text. It has inspired countless numbers of East Asians, especially in China, Japan and Korea, where Chan inspired traditions – Chan, Zen, and Son – have taken root and flourished for many centuries. Indeed, the influence has been so profound and pervasive it is hard to imagine Japanese and Korean cultures without it. In the twentieth century, Western audiences also became enthralled with stories of illustrious Zen masters, many of which are rooted in the Jingde chuandeng lu. I remember meeting Alan Ginsburg, intrepid Beat poet and inveterate Buddhist aspirant, in Shanghai in 1985. He had been invited as part of a literary cultural exchange between China and the U. S., to perform a series of lectures for students at Fudan University, where I was a visiting student. Eager to meet people who he could discuss Chinese Buddhism with, I found myself ushered into his company to converse on the subject. -

Fenghuang and Phoenix: Translation of Culture

International Journal of Languages, Literature and Linguistics, Vol. 6, No. 3, September 2020 Fenghuang and Phoenix: Translation of Culture Lyujie Zhu Confucius‟ time, fenghuang was mainly used to describe Abstract—Fenghuang and phoenix from ancient myths are virtuous man, such as shi and king, and it was in Han dynasty both culture-loaded words that have unique features and that fenghuang‟s gender was gradually distinguished [18], as comprehensive historical developing routes. This paper focuses the male feng with the female huang respectively, in on their translations to find out the reflected cultural issues and symbolizing everlasting love that representing the yin-yang power influences under the ideas of cultural identity and language power. Classic literatures like The Analects and The balance. After Ming-Qing period, fenghuang was major Tempest in bilingual versions are compared in terms of the symbolization for female that such transformation is translation for both animals, as well as by searching the unavoidably related to the monarchal power of Chinese different social backgrounds and timelines of those literatures. empresses in indicating themselves by using The mixed usage of phoenix and fenghuang in both Chinese fenghuang-elements [16]. (East) and English (West) culture makes confusions but also As for phoenix in the West, it has the totally different enriches both languages and cultures. origins and characteristics. Phoenix dies in its nest, and then Index Terms—Fenghuang, phoenix, translation, language, is reborn from its own burned ashes, with a duration of about cultural identity. 500 years [19]. Phoenix is said to be originated from Egyptian solar myths of the sacred bird, benu, through association with the self-renewing solar deity, Osiris [20]. -

PENANG CHINESE CUSTOMS and TRADITIONS1 Goh Sang

Kajian Malaysia, Vol. 33, Supp. 2, 2015, 135–152 PENANG CHINESE CUSTOMS AND TRADITIONS1 Goh Sang Seong School of Humanities, Universiti Sains Malaysia, MALAYSIA Email: [email protected] The Chinese first settled in Penang about two centuries ago bringing along with them their cultural practices from China. However, with the passing of time their cultural practices had undergone significant changes especially among the Hokkien Chinese who comprise the majority of the Chinese community in Penang. This essay examines the customs and traditions of the Penang Chinese from the aspects of beliefs and prayer ceremonies, festive celebrations, artefacts and daily activities in a more comprehensive manner. The influences of modern education and geographical environments have resulted in the evolution of their own unique and distinctive variation of Chinese customs. Their festive celebrations, beliefs, practices and daily activities reveal the inheritance from their ancestors from China besides the incorporation of Malay sociocultural elements. In fact, some customs are peculiar only to the Penang Hokkien who had to survive in an environment that was different from China although these customs are still based on traditional Chinese concepts and philosophy. The difference is the way in which these customs and traditions are celebrated. Present day Penang Chinese remain loyal to traditional customs brought by their ancestors from China although there is evidence of assimilation with Malay elements. Keywords: Penang Chinese, customs, heritage, Malay elements INTRODUCTION As early as the 15th century, Penang (known to the Chinese as Bin Lang Yu) had already existed on the map used by Admiral Cheng Ho in his expeditions to Southeast and Central Asia (Tan, 2007: 17). -

Names of Chinese People in Singapore

101 Lodz Papers in Pragmatics 7.1 (2011): 101-133 DOI: 10.2478/v10016-011-0005-6 Lee Cher Leng Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore ETHNOGRAPHY OF SINGAPORE CHINESE NAMES: RACE, RELIGION, AND REPRESENTATION Abstract Singapore Chinese is part of the Chinese Diaspora.This research shows how Singapore Chinese names reflect the Chinese naming tradition of surnames and generation names, as well as Straits Chinese influence. The names also reflect the beliefs and religion of Singapore Chinese. More significantly, a change of identity and representation is reflected in the names of earlier settlers and Singapore Chinese today. This paper aims to show the general naming traditions of Chinese in Singapore as well as a change in ideology and trends due to globalization. Keywords Singapore, Chinese, names, identity, beliefs, globalization. 1. Introduction When parents choose a name for a child, the name necessarily reflects their thoughts and aspirations with regards to the child. These thoughts and aspirations are shaped by the historical, social, cultural or spiritual setting of the time and place they are living in whether or not they are aware of them. Thus, the study of names is an important window through which one could view how these parents prefer their children to be perceived by society at large, according to the identities, roles, values, hierarchies or expectations constructed within a social space. Goodenough explains this culturally driven context of names and naming practices: Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore The Shaw Foundation Building, Block AS7, Level 5 5 Arts Link, Singapore 117570 e-mail: [email protected] 102 Lee Cher Leng Ethnography of Singapore Chinese Names: Race, Religion, and Representation Different naming and address customs necessarily select different things about the self for communication and consequent emphasis. -

Un/Sceghs/15/Inf.8 Committee of Experts on the Transport of Dangerous Goods and on the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals

UN/SCEGHS/15/INF.8 COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS ON THE TRANSPORT OF DANGEROUS GOODS AND ON THE GLOBALLY HARMONIZED SYSTEM OF CLASSIFICATION AND LABELLING OF CHEMICALS Sub-Committee of Experts on the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals Fifteenth session, Geneva, 9-11 July 2008 Item 7 of the provisional agenda OTHER BUSINESS Application for consultative status by the International Fireworks Association (IFA) Note by the secretariat 1. The secretariat reproduces below information received from the International Fireworks Association (IFA) requesting consultative status as a non-governmental organization for participation in the work of the Sub-Committee of Experts on the Globally Harmonized System of Classification and Labelling of Chemicals. 2. The Sub-Committee is invited to decide whether IFA may participate in its work with a consultative status. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in the attachment do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Application for Consultative Status With the Economic and Social Council Application documents from International Fireworks Association (IFA) Content 1.—(2) Application letter 2.—(3-11) Application form 3.—(12) Introduction of International Fireworks Association 4.—(13-16) Charters of International Fireworks Association 5.—(17) -

Middle Byzantine Appropriation of the Chinese Feng-Huang Bird Alicia Walker Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College History of Art Faculty Research and Scholarship History of Art 2010 Patterns of Flight: Middle Byzantine Appropriation of the Chinese Feng-Huang Bird Alicia Walker Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs Custom Citation Alicia Walker, "Patterns of Flight: Middle Byzantine Appropriation of the Chinese Feng-Huang Bird," Ars Orientalis 37 (2010): 188-216. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/hart_pubs/56 For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARS ORIENTALIS 38 ars orientalis 38 ars orientalis volume 38 issn 0571–1371 Printed in the United States of America editorial board © 2010 Smithsonian Institution, Lee Glazer and Jane Lusaka, co-editors Washington, D.C. Martin J. Powers Debra Diamond Cosponsored by the Department of the History of Art, University of Michigan, and the Massumeh Farhad Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Institution, Ars Orientalis solicits scholarly manuscripts Thelma K. Thomas on the art and archaeology of Asia, including the ancient Near East and the Islamic world. Fostering a broad range of themes and approaches, articles of interest to scholars in diverse editorial committee fields or disciplines are particularly sought, as are suggestions for occasional thematic issues Sussan Babaie and reviews of important books in Western or Asian languages. Brief research notes and Kevin Carr responses to articles in previous issues of Ars Orientalis will also be considered. -

Religion and Nationalism in Chinese Societies

RELIGION AND SOCIETY IN ASIA Kuo (ed.) Kuo Religion and Nationalism in Chinese Societies Edited by Cheng-tian Kuo Religion and Nationalism in Chinese Societies Religion and Nationalism in Chinese Societies Religion and Society in Asia The Religion and Society in Asia series presents state-of-the-art cross-disciplinary academic research on colonial, postcolonial and contemporary entanglements between the socio-political and the religious, including the politics of religion, throughout Asian societies. It thus explores how tenets of faith, ritual practices and religious authorities directly and indirectly impact on local moral geographies, identity politics, political parties, civil society organizations, economic interests, and the law. It brings into view how tenets of faith, ritual practices and religious authorities are in turn configured according to socio-political, economic as well as security interests. The series provides brand new comparative material on how notions of self and other as well as justice and the commonweal have been predicated upon ‘the religious’ in Asia since the colonial/imperialist period until today. Series Editors Martin Ramstedt, Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, Halle Stefania Travagnin, University of Groningen Religion and Nationalism in Chinese Societies Edited by Cheng-tian Kuo Amsterdam University Press This book is sponsored by the 2017 Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange (Taiwan; SP002-D-16) and co-sponsored by the International Institute of Asian Studies (the Netherlands). Cover illustration: Chairman Mao Memorial Hall in Beijing © Cheng-tian Kuo Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Typesetting: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press.