1 Sustainable Mitigation Techniques for Coffee Leaf Rust in Loma Linda

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hemileia Vastatrix) on Coffee, in Chanchamayo (Junín-Peru) 1

Agronomía Mesoamericana ISSN: 2215-3608 [email protected] Universidad de Costa Rica Costa Rica Dynamics of severity of coffee leaf rust (Hemileia vastatrix) on Coffee, in Chanchamayo (Junín-Peru) 1 Alvarado-Huamán, Leonel; Borjas-Ventura, Ricardo; Castro-Cepero, Viviana; García-Nieves, Leslie; Jiménez-Dávalos, Jorge; Julca-Otiniano, Alberto; Gómez-Pando, Luz 1 Dynamics of severity of coffee leaf rust (Hemileia vastatrix) on Coffee, in Chanchamayo (Junín-Peru) Agronomía Mesoamericana, vol. 31, no. 3, 2020 Universidad de Costa Rica, Costa Rica Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=43764233001 DOI: https://doi.org/10.15517/am.v31i3.39726 © 2020 Agronomía Mesoamericana es desarrollada en la Universidad de Costa Rica bajo una licencia Creative Commons Atribución-NoComercial-SinDerivar 4.0 Internacional. Para más información escriba a [email protected], [email protected] This work is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International. PDF generated from XML JATS4R by Redalyc Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Leonel Alvarado-Huamán, et al. Dynamics of severity of coffee leaf rust (Hemileia vastatrix) on C... Artículo Dynamics of severity of coffee leaf rust (Hemileia vastatrix) on Coffee, in Chanchamayo (Junín-Peru) 1 Dinámica de la severidad de la roya (Hemileia vastatrix) en café, en Chanchamayo (Junín-Perú) Leonel Alvarado-Huamán DOI: https://doi.org/10.15517/am.v31i3.39726 Universidad Nacional Agraria La Molin, Perú Redalyc: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa? -

Studies of the Laboulbeniomycetes: Diversity, Evolution, and Patterns of Speciation

Studies of the Laboulbeniomycetes: Diversity, Evolution, and Patterns of Speciation The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40049989 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA ! STUDIES OF THE LABOULBENIOMYCETES: DIVERSITY, EVOLUTION, AND PATTERNS OF SPECIATION A dissertation presented by DANNY HAELEWATERS to THE DEPARTMENT OF ORGANISMIC AND EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Biology HARVARD UNIVERSITY Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2018 ! ! © 2018 – Danny Haelewaters All rights reserved. ! ! Dissertation Advisor: Professor Donald H. Pfister Danny Haelewaters STUDIES OF THE LABOULBENIOMYCETES: DIVERSITY, EVOLUTION, AND PATTERNS OF SPECIATION ABSTRACT CHAPTER 1: Laboulbeniales is one of the most morphologically and ecologically distinct orders of Ascomycota. These microscopic fungi are characterized by an ectoparasitic lifestyle on arthropods, determinate growth, lack of asexual state, high species richness and intractability to culture. DNA extraction and PCR amplification have proven difficult for multiple reasons. DNA isolation techniques and commercially available kits are tested enabling efficient and rapid genetic analysis of Laboulbeniales fungi. Success rates for the different techniques on different taxa are presented and discussed in the light of difficulties with micromanipulation, preservation techniques and negative results. CHAPTER 2: The class Laboulbeniomycetes comprises biotrophic parasites associated with arthropods and fungi. -

Pests and Diseases of Coffee in East Africa

Pests and Diseases of Coffee in Eastern Africa: A Technical and Advisory Manual compiled & edited by Mike A. Rutherford CABI UK Centre (Ascot) and Noah Phiri CABI Africa Regional Centre (Nairobi) Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank all those who contributed towards the preparation of this manual, in terms of provision of information, photographic material and advice. Gratitude is also extended to the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID) for providing financial report through the Renewable Natural Resources Research Strategy Crop Protection Programme (RNRRS CPP). Copyright statement © Copyright CAB International (2006) Extracts of this publication may be freely reproduced and distributed on a non-commercial basis for teaching and training purposes only, providing that the source is clearly acknowledged as: CAB International (2006) Pests and diseases of coffee in eastern Africa: a technical and advisory manual. CAB International, Wallingford, UK Compiled & edited by Mike Rutherford and Noah Phiri The copyright works may not be used for any other purpose without the express written consent of CAB International (trading as CABI), and such notice shall be placed on all copies distributed by whatever means. This publication is an output from the Crop Protection Programme of the UK Department for International Development (DFID), for the benefit of developing countries. The views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID. 2 CONTENTS Page no. Part 1 Introduction 4 Part 2 Coffee Pests 7 Coffee Berry Borer -

Coffee Leaf Rust Is Bad News

Coffee leaf rust is bad news Published 5 October 2020, with Stuart McCook.1 When I think of Ceylon — Sri Lanka — I think of tea, but that’s because I wasn’t alive 150 years ago. In the 1860s, coffee was the island’s most important crop. Coffee leaf rust, a fungus, put paid to the coffee, but only after a global downturn in coffee prices, and planters switched to tea. The rust, however, is not the reason the Brits drink tea rather than coffee, just one of the things I learned from Stuart McCook, who has studied the history of coffee leaf rust and what it might hold for the future. Stuart McCook: My name is Stuart McCook. I am a historian at the University of Guelph in Ontario, Canada, and my research focuses on the environmental history of coffee. Most recently I've published a book called Coffee is Not Forever which is a global history of the coffee leaf rust. Coffee leaf rust is a fungus which is native to equatorial Africa. You can think of it running from western Africa in Liberia through to the eastern part of Africa; Kenya, Ethiopia, and places like that. Jeremy: Of course, it didn't stay in Africa. When coffee went global, so, eventually, did coffee leaf rust. We'll get to that. First, though, there's something we need to get out of the way right at the outset. Like many of the diseases that attack our favourite commodities, in the short term, at least, coffee leaf rust is not a threat to your coffee. -

6 Production Details of Organic Tea Estates in Sri Lanka

Status of organic agriculture in Sri Lanka with special emphasis on tea production systems (Camellia sinensis (L.) O. Kuntze) Dissertation zur Erlangung des Grades „Doktor der Agrarwissenschaften“ am Fachbereich Pflanzenbau der Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen PhD Thesis Faculty of Plant Production, Justus-Liebig-University of Giessen vorgelegt von / submitted by Ute Williges OCTOBER 2004 Acknowledgement The author gratefully acknowledges the financial assistance received from the German Academic Exchange Service (Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst, DAAD) for the field work in Sri Lanka over a peroid of two years and the „Hochschul- und Wissenschaftsprogramm (HWP)“ for supporting the compilation of the thesis afterwards in Germany. My sincere thanks goes to my teacher Prof. Dr. J. Sauerborn whose continuous supervision and companionship accompanied me throughout this work and period of live. Further I want to thank Prof. Dr. Wegener and Prof. Dr. Leithold for their support regarding parts of the thesis and Dr. Hollenhorst for his advice carrying out the statistical analysis. My appreciation goes to Dr. Nanadasena and Dr. Mohotti for their generous provision of laboratory facilities in Sri Lanka. My special thanks goes to Mr. Ekanayeke whose thoughts have given me a good insight view in tea cultivation. I want to mention that parts of the study were carried out in co-operation with the Non Governmental Organisation Gami Seva Sevana, Galaha, Bio Foods (Pvt) Ltd., Bowalawatta, the Tea Research Institute (TRI) of Sri Lanka, Talawakele; The Tea Small Holders Development Authority (TSHDA), Regional Extension Centre, Sooriyagoda; The Post Graduate Institute of Agriculture (PGIA), Department of Soil Science, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya and The Natural Resources Management Services (NRMS), Mahaweli Authority of Sri Lanka, Polgolla. -

A Thesis Entitled Influence of Soil-Quality on Coffee-Plant Quality

A Thesis entitled Influence of Soil-Quality on Coffee-Plant Quality and a Complex Tropical Insect Food Web by David J. Gonthier Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science in Biology (Ecology track) Dr. Stacy Philpott, Committee Chair Dr. Scott Heckathorn, Committee Member Dr. Ivette Perfecto, Committee Member Dr. Patricia Komuniecki, Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo May 2010 Copyright 2010, David J. Gonthier This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author. An Abstract of Influence of Soil-Quality on Coffee-Plant Quality and a Complex Tropical Insect Food Web by David J. Gonthier Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science in Biology (Ecology track) The University of Toledo May 2010 Tropical systems are complex, species diverse, and are often regulated by top-down forces (higher trophic levels control lower trophic levels). In many ecosystems insects, especially herbivores and their mutualists, may be strongly affected by plant quality and other bottom-up controls (nutrient availability, plant genetic variation, ect.). Yet few have asked how plant quality (nutritional and defensive plant traits) can contribute to the population regulation and the complexity of these systems. In this thesis, I investigate the importance of soil-quality to both the elemental and secondary metabolite content in coffee and ask how changes to plant quality can influence hemipteran herbivores, their ant-mutualists, predators, and insect communities in a tropical coffee agroecosystem. -

Obituary Notice

obituary notice ... dean of the world’s living hemp breeders. ... the world's foremost expert on hemp. ... elder statesman of the exploding hemp movement. ... world-renowned expert on hemp breeding and cultivation. ... the eldest, and one of the most successful, active hemp breeders of Europe. ... hemp guru. Dr Bócsa Iván Born: Arad, July 09, 1926 Died: Budapest, May 04, 2007 1948 Fleischmann Rudolf Kompolt Institute 1970 February 15, 1949 February 15, 1949 57 years Alfalfa – Medicago sativa L. Sainfoin – Onobrychis viciifolia Scop. Crown wetch – Coronilla varia L. Hemp – Cannabis sativa L. “Energy grass” Italian hemp Fleischmann = = F-kender (1923) Fleischmann Rudolf 1920 • biology of flowering • photoperiodism • heterosis (F-kender x Kymington (USA) Italian hemp Fleischmann = = F-kender (1923) Reconstruction (1951) Bócsa (1951-): fiber content increase Fleischmann Rudolf 1920 Kompolti by Bredemann method • biology of flowering (1954) • photoperiodism • heterosis (F-kender x Kymington (USA) preservation breeding Czechoslovakia, Bulgaria, Romania, Yugoslavia ... 1995- : Holland, Austria England, Germany, Switzerland Kompolti Kínai B-7 F1 + 23% straw yield 1954 + 18% fiber yield Breeding of F1 cultivar-hybrid hemp (Bócsa, 1950-) Ukrainian monoecious CENTRAL SOUTHERN ASIATIC RUSSIAN dioecious monoiecious dioecious and unisexual TRANSITIONAL French monoecious an hybrids Hemp ecological form groups Kínai Fibrimon 21 (dioecious) F1 Kinai Backcross BC1 Kínai Kínai (monoecious) Breeding of monoecious hemp (Bócsa, 1953-1960) Dioecious (SE -

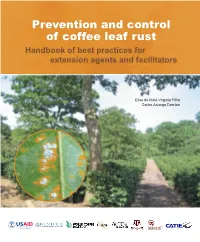

Prevention and Control of Coffee Leaf Rust Handbook of Best Practices for Extension Agents and Facilitators

Prevention and control of coffee leaf rust Handbook of best practices for extension agents and facilitators Elias de Melo Virginio Filho Carlos Astorga Domian Technical series Technical manual no. 131 Prevention and control of coffee leaf rust Handbook of best practices for extension agents and facilitators Elias de Melo Virginio Filho Carlos Astorga Domian Tropical Agricultural Research and Higher Education Center (CATIE) August 2019 CATIE does not assume responsibility for the opinions and statements expressed in this document by the authors. The ideas of the authors do not necessarily reflect the point of view of the institution. Partial repro- duction of the information is authorized, as long as the source is cited. © Tropical Agricultural Research and Higher Education Center (CATIE), 2019 ISBN: 978-9977-57-704-3 Credits Authors Elias de Melo Virginio Filho Carlos Astorga Domian Reviewers: Jacques Avelino Mirna Barrios Rolando Cerda Kauê de Sousa Edition Layout: Rocío Jiménez Salas, CATIE Photography: Jacques Avelino: p.14; Shirley Orozco: p. 18, 25; Isabelle Merle: p. 19; Silvia Chaves: p. 33; Shaline Fernandes: p. 44, 83; Elias de Melo V.F.: p. 48, 58, 70, 76. Translation: Elena M. Florian Content Presentation ................................................................................5 Acknowledgments ..........................................................................6 Acronyms ...................................................................................7 Relevance and how to use the handbook ..................................................8 Section I. Disease characterization...................................................... 10 Chapter 1. Origin, epidemics and impacts of coffee leaf rust ........................... 10 1.1 Origin and distribution of coffee leaf rust in the world . 11 1.2 Epidemics and impacts of coffee rust on production and economy ........... 13 1.3 How to develop a technical session with coffee farmers ...................... 16 References .................................................................... -

Phylogenetic Analysis of Hemileia Vastatrix and Related Taxa Using a Genome-Scale Approach Diogo N

Phylogenetic analysis of Hemileia vastatrix and related taxa using a genome-scale approach Diogo N. Silva, Ana Vieira, Pedro Talhinhas, Helena Gil Azinheira, Maria Do Ceu Silva, Diana Fernandez, Octavio S Paulo, Sébastien Duplessis, Dora Batista To cite this version: Diogo N. Silva, Ana Vieira, Pedro Talhinhas, Helena Gil Azinheira, Maria Do Ceu Silva, et al.. Phylogenetic analysis of Hemileia vastatrix and related taxa using a genome-scale approach. 24. International Conference on Coffee Science. ASIC 2012, Nov 2012, San Jose, Costa Rica. hal- 01267895 HAL Id: hal-01267895 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01267895 Submitted on 3 Jun 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Phylogenetic analysis of Hemileia vastatrix and related taxa using a genome-scale approach SILVA, DIOGO N.*¥, VIEIRA, ANA*, TALHINHAS, PEDRO*, AZINHEIRA, HELENA G.*, SILVA, MARIA DO CÉU*, FERNANDEZ, DIANA§, DUPLESSIS, SÉBASTIEN£, PAULO, OCTÁVIO S¥, BATISTA, DORA*. * CIFC/IICT - Centro de Investigação das Ferrugens do Cafeeiro/Instituto de Investigação Científica -

Vote:125 National Animal Genetic Res

Agriculture Vote Budget Framework Paper FY 2020/21 Vote:125 National Animal Genetic Res. Centre and Data Bank V1: Vote Overview (i) Snapshot of Medium Term Budget Allocations Table V1.1: Overview of Vote Expenditures Billion Uganda Shillings FY2018/19 FY2019/20 FY2020/21 MTEF Budget Projections Approved Spent by Proposed 2021/22 2022/23 2023/24 2024/25 Outturn Budget End Sep Budget Recurrent Wage 2.526 4.028 0.970 4.028 4.028 4.028 4.028 4.028 Non Wage 1.553 5.870 1.048 5.870 7.044 8.453 10.144 12.173 Devt. GoU 6.324 53.344 7.480 53.344 53.344 53.344 53.344 53.344 Ext. Fin. 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 GoU Total 10.403 63.242 9.498 63.242 64.416 65.825 67.516 69.545 Total GoU+Ext Fin 10.403 63.242 9.498 63.242 64.416 65.825 67.516 69.545 (MTEF) A.I.A Total 2.004 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 Grand Total 12.407 63.242 9.498 63.242 64.416 65.825 67.516 69.545 (ii) Vote Strategic Objective 1. Enhance Animal Genetic Improvement efforts for increased animal Production and Productivity. 2. Conservation of Biodiversity, Sustainable Utilization and Development of Indigenous Animal Genetic resources. 3. Strengthened Institutional capacity, growth and development. 4. Client oriented services, collaborations, and entrepreneurship. 5. Establish a National Animal information resource and development centre. -

Wax Structures of Scymnus Louisianae Attenuate Aggression from Aphid-Tending Ants

CHEMICAL ECOLOGY Wax Structures of Scymnus louisianae Attenuate Aggression From Aphid-Tending Ants EZRA G. SCHWARTZBERG,1,2 KENNETH F. HAYNES,1 DOUGLAS W. JOHNSON,1 1 AND GRAYSON C. BROWN Environ. Entomol. 39(4): 1309Ð1314 (2010); DOI: 10.1603/EN09372 ABSTRACT The cuticular wax structures of Scymnus louisianae J. Chapin larvae were investigated as a defense against ant aggression by Lasius neoniger Emery. The presence of wax structures provided signiÞcant defense against ant aggression compared with denuded larvae in that these structures attenuated the aggressive behavior of foraging ants. Furthermore, reapplication of wax dissolved in hexane partially restored defenses associated with intact structures, showing an attenuation of aggression based in part on cuticular wax components rather than solely on physical obstruction to ant mouthparts. KEY WORDS Scymnus louisianae, Aphis glycines, Lasius neoniger, ant-tending Many ants tend aphids and use the collected honeydew wax in promoting physical obstruction to the mouthparts as a sugar source. In return, the aphids beneÞt from the of aphid-tending ants, little has been done to elucidate tending ants (Way 1963, Ho¨lldobler and Wilson 1990). In the role that wax plays in eliciting avoidance behavior or these systems, aphids can beneÞt through reduced pre- in attenuating aggression. SpeciÞcally, physical or chem- dation (Banks 1962) and increased Þtness (Flatt and ical mimicry, camoußage, or repellency has not been Weisser 2000). The relationship between ants and aphids looked at as a potential means of avoidance of ant ag- is often a mutualistic one but ranges from obligatory to gression in the Scymnus beetles. It has been suggested facultative (Dixon 1998). -

Status Report on Arthropod Predators of the Asian Citrus Psyllid in Mexico

Status report on arthropod predators of the Asian Citrus Psyllid in Mexico Esteban Rodríguez-Leyva Colegio de Postgraduados, Montecillo, Texcoco, MEXICO. Importance of Citrus in Mexico 525 000 ha 23 States Citrus production 6.7 million ton/year 68% Orange, 20% Mexican lime, 5% Persian lime 2.5% Grapefruit , 2.5% Tangerine The insect problem Diaphorina citri in Mexico (www.senasica.gob.mx) Searching for natural enemies of ACP on citrus trees and orange jessamine Coccinellidae Azya orbigera Brachiacantha decora Chilocorus cacti Cycloneda sanguinea Harmonia axyridis Hippodamia convergens Olla v-nigrum López- Arroyo et al. 2008 Marín 2009, personal com. Sánchez-González & Arredondo-Bernal 2009, personal com. Gaona-García et al. 2009 Chrysopidae Chrysoperla rufilabris C. comanche C. externa Ceraeochrysa sp. nr. cincta C. valida López- Arroyo et al. 2008 Cortez-Mondaca et al. 2008 Syrphidae Allographa obliqua Pseudodoros clavatus Toxomerus marginatus Toxomerus politus Miscelaneous predators of ACP Spiders, Wasps (Vespidae), Ants (Ponerinae) López- Arroyo et al. 2008 Sánchez-González & Arredondo-Bernal 2009, personal com. Abundance of ladybirds (Coccinellidae) predators on citrus trees, at Nuevo Leon (northeast), Mexico. (Insect net, two sides of each mature tree, n=30). López-Arroyo, 2010, personal com. Abundance of lacewings (Chrysopidae) predators on citrus trees, at Nuevo Leon (northeast), Mexico. (Insect net two sides of each mature tree, n=30). López-Arroyo, 2010, personal com. Abundance of lacewings (Chrysopidae) predators on citrus trees, at Nuevo Leon (northeast), Mexico. (Insect net two sides of each mature tree, n=30). López-Arroyo, 2010, personal com. Abundance of predators (specially C. rufilabris) on Diaphorina citri on citrus trees at Nuevo Leon (northeast), Mexico.