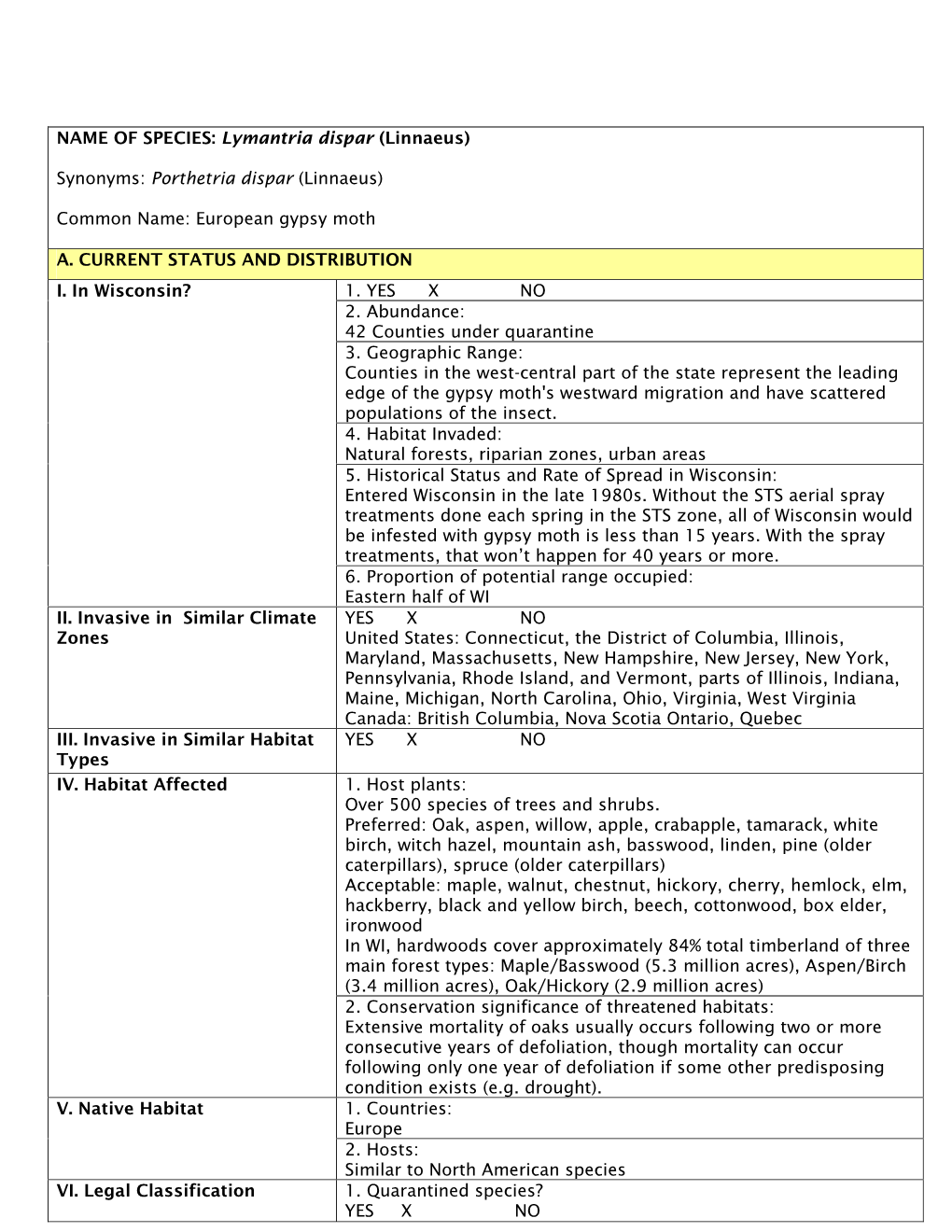

NAME of SPECIES: Lymantria Dispar (Linnaeus)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entomofauna Ansfelden/Austria; Download Unter

©Entomofauna Ansfelden/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Entomofauna ZEITSCHRIFT FÜR ENTOMOLOGIE Band 28, Heft 28: 377-388 ISSN 0250-4413 Ansfelden, 30. November 2007 Phytophagous Noctuidae (Lepidoptera) of the Western Black Sea Region and their ichneumonid parasitoids Z. OKYAR & M. YURTCAN Abstract Eleven agricultural and silviculturally important species of Noctuidae and their parasitoids were determined in 33 localities from the Western Black Sea region between 2001 and 2004. The ichneumonid biological control agents Enicospilus ramidulus, Barylypa amabilis and Itoplectis alternans were obtained by rearing the host larvae. K e y w o r d s : Lepidoptera, Noctuidae, Hymenoptera, Ichneumonidae, parasitoidism, Western Black Sea Region, Turkey Zusammenfassung 11 land- und forstwirtschaftlich bedeutende Noctuidae-Arten einschließlich ihrer Parasitoide aus 33 Standorten des Gebietes des westlichen Schwarzen Meeres wurden im Zeitraum 2001 bis 2004 studiert. Ichneumonidae der Arten Enicospilus ramidulus, Barylypa amabilis and Itoplectis alternans konnten durch Aufzucht der Wirtslarven festgestellt werden. 377 ©Entomofauna Ansfelden/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Introduction The Noctuidae is the largest family of the Lepidoptera. Larvae of some species are par- ticularly harmful to agricultural and silvicultural regions worldwide. Consequently, for years intense efforts have been carried out to control them through chemical, biological, and cultural methods (LIBURD et al. 2000; HOBALLAH et al. 2004; TOPRAK & GÜRKAN 2005). In the field, noctuid control is often carried out by parasitoid wasps (CHO et al. 2006). Ichneumonids are one of the most prevalent parasitoid groups of noctuids but they also parasitize on other many Lepidoptera, Coleoptera, Hymenoptera, Diptera and Araneae (KASPARYAN 1981; FITTON et al. 1987, 1988; GAULD & BOLTON 1988; WAHL 1993; GEORGIEV & KOLAROV 1999). -

Range Expansion of Lymantria Dispar Dispar (L.) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) Along Its North‐Western Margin in North America Despite Low Predicted Climatic Suitability

Received: 22 December 2017 | Revised: 9 August 2018 | Accepted: 11 September 2018 DOI: 10.1111/jbi.13474 RESEARCH PAPER Range expansion of Lymantria dispar dispar (L.) (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) along its north‐western margin in North America despite low predicted climatic suitability Marissa A. Streifel1,2 | Patrick C. Tobin3 | Aubree M. Kees1 | Brian H. Aukema1 1Department of Entomology, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, Minnesota Abstract 2Minnesota Department of Agriculture, Aim: The European gypsy moth, Lymantria dispar dispar (L.), (Lepidoptera: Erebidae) St. Paul, Minnesota is an invasive defoliator that has been expanding its range in North America follow- 3School of Environmental and Forest Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, ing its introduction in 1869. Here, we investigate recent range expansion into a Washington region previously predicted to be climatically unsuitable. We examine whether win- Correspondence ter severity is correlated with summer trap captures of male moths at the landscape Brian Aukema, Department of Entomology, scale, and quantify overwintering egg survivorship along a northern boundary of the University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN. Email: [email protected] invasion edge. Location: Northern Minnesota, USA. Funding information USDA APHIS, Grant/Award Number: Methods: Several winter severity metrics were defined using daily temperature data A-83114 13255; National Science from 17 weather stations across the study area. These metrics were used to explore Foundation, Grant/Award Number: – ‐ 1556111; United States Department of associations with male gypsy moth monitoring data (2004 2014). Laboratory reared Agriculture Animal Plant Health Inspection egg masses were deployed to field locations each fall for 2 years in a 2 × 2 factorial Service, Grant/Award Number: 15-8130- / × / 0577-CA; USDA Forest Service, Grant/ design (north south aspect below above snow line) to reflect microclimate varia- Award Number: 14-JV-11242303-128 tion. -

Hawk Moths of North America Is Richly Illustrated with Larval Images and Contains an Abundance of Life History Information

08 caterpillars EUSA/pp244-273 3/9/05 6:37 PM Page 244 244 TULIP-TREE MOTH CECROPIA MOTH 245 Callosamia angulifera Hyalophora cecropia RECOGNITION Frosted green with shiny yellow, orange, and blue knobs over top and sides of body. RECOGNITION Much like preceding but paler or Dorsal knobs on T2, T3, and A1 somewhat globular and waxier in color with pale stripe running below set with black spinules. Paired knobs on A2–A7 more spiracles on A1–A10 and black dots on abdomen cylindrical, yellow; knob over A8 unpaired and rounded. lacking contrasting pale rings. Yellow abdominal Larva to 10cm. Caterpillars of larch-feeding Columbia tubercle over A8 short, less than twice as high as broad. Silkmoth (Hyalophora columbia) have yellow-white to Larva to 6cm. Sweetbay Silkmoth (Callosamia securifera) yellow-pink instead of bright yellow knobs over dorsum similar in appearance but a specialist on sweet bay. Its of abdomen and knobs along sides tend to be more white than blue (as in Cecropia) and are yellow abdominal tubercle over A8 is nearly three times as set in black bases (see page 246). long as wide and the red knobs over thorax are cylindrical (see page 246). OCCURRENCE Urban and suburban yards and lots, orchards, fencerows, woodlands, OCCURRENCE Woodlands and forests from Michigan, southern Ontario, and and forests from Canada south to Florida and central Texas. One generation with mature Massachusetts to northern Florida and Mississippi. One principal generation northward; caterpillars from late June through August over most of range. two broods in South with mature caterpillars from early June onward. -

2 Mechanisms Behind the Usurpation of Thyrinteina Leucocerae By

Mechanisms behind the Usurpation of Thyrinteina leucocerae by Glyptapanteles sp. Introduction It has frequently been proposed that parasites purposefully manipulate their hosts in order to increase their fitness, usually to the detriment of the host (Lefevre et al. 2008, Poulin & Thomas 1999). A recent hypothesis known as the ‘usurpation hypothesis’ argues that parasites manipulate hosts in such a way that the host guards their larvae from hyperparasitoids, or predators of the parasitoids (Harvey et al. 2008). Examples demonstrating the usurpation hypothesis are limited, but a few compelling instances do exist. In one system, parasitoid wasps cause aphid hosts to mummify in more concealed sites in order to protect diapausing aphid larva (Brodeur & McNeil 1989). The parasitoid Hymenoepimecis sp. has also been shown to induce its spider host Plesiometa argyra to build a specialized web designed to carry developing parasitoid cocoons (Eberhard 2000). It appears that the wasps may utilize some kind of fast acting chemical, as removal of the wasp larva results in spiders reverting back to normal web construction (Eberhard 2001). While these examples are compelling, evidence for the specific mechanisms utilized by parasitoids to alter their host’s behavior is largely unknown. However, a recent system of study may provide interesting insight on the mechanisms behind host usurpation. In this system parasitic wasps lay their eggs in the larva of caterpillars until they are ready to egress from the caterpillar and pupate (Grosman et al. 2008). Following parasite egression the host caterpillars cease to feed and walk, and defend the parsitoid pupae by producing head swings against approaching predators (Grosman et al. -

Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis Persius Persius

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis persius persius in Canada ENDANGERED 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis persius persius in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 41 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge M.L. Holder for writing the status report on the Eastern Persius Duskywing Erynnis persius persius in Canada. COSEWIC also gratefully acknowledges the financial support of Environment Canada. The COSEWIC report review was overseen and edited by Theresa B. Fowler, Co-chair, COSEWIC Arthropods Species Specialist Subcommittee. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur l’Hespérie Persius de l’Est (Erynnis persius persius) au Canada. Cover illustration: Eastern Persius Duskywing — Original drawing by Andrea Kingsley ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2006 Catalogue No. CW69-14/475-2006E-PDF ISBN 0-662-43258-4 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – April 2006 Common name Eastern Persius Duskywing Scientific name Erynnis persius persius Status Endangered Reason for designation This lupine-feeding butterfly has been confirmed from only two sites in Canada. -

1 International Publications Reviewed by Referees and Listed in SCI

International publications reviewed by referees and listed in SCI * Corresponding Author Karlhofer, J., Schafellner, C., Hoch, G.* 2012: Reduced activity of juvenile hormone esterase in microsporidia-infected Lymantria dispar larvae. J. Invertrebr. Pathol. Meurisse, N.*, Hoch, G., Schopf, A., Battisti, A., Gregoire, J.-C. 2012: Low temperature tolerance and starvation ability of the oak processionary moth: implications in a context of increasing epidemics. Agric. For. Entomol. Goertz, D.*, Hoch, G. 2011: Modeling horizontal transmission of microsporidia infecting gypsy moth, Lymantria dispar (L.), larvae. Biol. Contr. 56, 263-270. Hoch, G.*, Petrucco Toffolo, E., Netherer, S., Battisti, A., Schopf, A. 2009: Survival at low temperature of larvae of the pine processionary moth, Thaumetopoea pityocampa from an area of range expansion. Agric. For. Entomol. 11, 313-320. Goertz, D.*, Hoch, G. 2009: Three microsporidian pathogens infecting Lymantria dispar larvae do not differ in their success in horizontal transmission. J. Appl. Ent. 133, 568- 570. Hendrichs, J.*, Bloem, K., Hoch, G., Carpenter, J.E., Greany, P., Robinson, A.S. 2009: Improving the cost-effectiveness, trade and safety of biological control for agricultural insect pests using nuclear techniques. Biocontr. Sci. Techn, 19, S1, 3-22. Hoch, G.*, Solter, L.F., Schopf, A. 2009: Treatment of Lymantria dispar (Lepidoptera, Lymantriidae) host larvae with polydnavirus/venom of a braconid parasitoid increases spore production of entomopathogenic microsporidia. Biocontr. Sci. Techn. 19, S1, 35-42. Hoch, G.*, Marktl, R.C., Schopf, A. 2009: Gamma radiation-induced pseudoparasitization as a tool to study interactions between host insects and parasitoids in the system Lymantria dispar (Lep., Lymantriidae) - Glyptapanteles liparidis (Hym., Braconidae). -

CURRICULUM VITAE Matthew P. Ayres

CURRICULUM VITAE Matthew P. Ayres Department of Biological Sciences, Dartmouth College, Hanover, NH 03755 (603) 646-2788, [email protected], http://www.dartmouth.edu/~mpayres APPOINTMENTS Professor of Biological Sciences, Dartmouth College, 2008 - Associate Director, Institute of Arctic Studies, Dartmouth College, 2014 - Associate Professor of Biological Sciences, Dartmouth College, 2000-2008 Assistant Professor of Biological Sciences, Dartmouth College, 1993 to 2000 Research Entomologist, USDA Forest Service, Research Entomologist, 1993 EDUCATION 1991 Ph.D. Entomology, Michigan State University 1986 Fulbright Fellowship, University of Turku, Finland 1985 M.S. Biology, University of Alaska Fairbanks 1983 B.S. Biology, University of Alaska Fairbanks PROFESSIONAL AFFILIATIONS Ecological Society of America Entomological Society of America PROFESSIONAL SERVICES Member, Board of Editors: Ecological Applications; Member, Editorial Board, Population Ecology Referee: (10-15 manuscripts / year) American Naturalist, Annales Zoologici Fennici, Bioscience, Canadian Entomologist, Canadian Journal of Botany, Canadian Journal of Forest Research, Climatic Change, Ecography, Ecology, Ecology Letters, Ecological Entomology, Ecological Modeling, Ecoscience, Environmental Entomology, Environmental & Experimental Botany, European Journal of Entomology, Field Crops Research, Forest Science, Functional Ecology, Global Change Biology, Journal of Applied Ecology, Journal of Biogeography, Journal of Geophysical Research - Biogeosciences, Journal of Economic -

Lepidoptera: Noctuoidea: Erebidae) and Its Phylogenetic Implications

EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF ENTOMOLOGYENTOMOLOGY ISSN (online): 1802-8829 Eur. J. Entomol. 113: 558–570, 2016 http://www.eje.cz doi: 10.14411/eje.2016.076 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome of Spilarctia robusta (Lepidoptera: Noctuoidea: Erebidae) and its phylogenetic implications YU SUN, SEN TIAN, CEN QIAN, YU-XUAN SUN, MUHAMMAD N. ABBAS, SAIMA KAUSAR, LEI WANG, GUOQING WEI, BAO-JIAN ZHU * and CHAO-LIANG LIU * College of Life Sciences, Anhui Agricultural University, 130 Changjiang West Road, Hefei, 230036, China; e-mails: [email protected] (Y. Sun), [email protected] (S. Tian), [email protected] (C. Qian), [email protected] (Y.-X. Sun), [email protected] (M.-N. Abbas), [email protected] (S. Kausar), [email protected] (L. Wang), [email protected] (G.-Q. Wei), [email protected] (B.-J. Zhu), [email protected] (C.-L. Liu) Key words. Lepidoptera, Noctuoidea, Erebidae, Spilarctia robusta, phylogenetic analyses, mitogenome, evolution, gene rearrangement Abstract. The complete mitochondrial genome (mitogenome) of Spilarctia robusta (Lepidoptera: Noctuoidea: Erebidae) was se- quenced and analyzed. The circular mitogenome is made up of 15,447 base pairs (bp). It contains a set of 37 genes, with the gene complement and order similar to that of other lepidopterans. The 12 protein coding genes (PCGs) have a typical mitochondrial start codon (ATN codons), whereas cytochrome c oxidase subunit 1 (cox1) gene utilizes unusually the CAG codon as documented for other lepidopteran mitogenomes. Four of the 13 PCGs have incomplete termination codons, the cox1, nad4 and nad6 with a single T, but cox2 has TA. It comprises six major intergenic spacers, with the exception of the A+T-rich region, spanning at least 10 bp in the mitogenome. -

Browntail Moth and the Big Itch: Public Health Implications and Management of an Invasive Species

Browntail Moth and the Big Itch: Public Health Implications and Management of an Invasive Species July 22, 2021 Jill H. Colvin, MD, FAAD MDFMR Dermatology photo credits: Jon Karnes, MD Thomas E. Klepach, PhD Assistant Professor of Biology, Colby College Ward 3 City Councilor, Waterville, Maine Financial disclosure statement Jill H Colvin MD and Thomas E. Klepach, PhD do not have a financial interest/arrangement or affiliation with any organizations that could be perceived as a conflict of interest in the context of this presentation. OBJECTIVES • Identify: • Impacts of browntail moth (BTM) infestation on humans and the environment • Review: • Presentation and treatment of BTM dermatoses • Biology of the BTM • Population trends of the BTM • BTM mitigation strategies JUNE 2021, AUGUSTA, MAINE PERVASIVE! COMPLICATIONS OF INVASIVE BROWNTAIL MOTH SOCIAL MEDIA RADIO ARBORISTS PHARMACY NEWSPAPERS FRIENDS COLLEAGUES HEALTH CARE FAMILY TEXTS TOURISM PATIENTS MAINE.GOV SELF REALTY PHONE CALLS ACTIVISM TREES SOCIAL MEDIA IMPACT: TOURISM, REAL ESTATE, DAILY LIFE Maine.gov Maine.gov Photo credit: Jon Karnes, MD Photo credit: Robert Kenney, DO BTM: Risk to Human Health Mediated by: Toxic hairs on caterpillars, female moths, environment Direct contact Airborne Damage skin, eye, airway in multiple ways Mechanical: Barbs on hair Chemical: toxin Irritant Allergen One report of Death – 1914: ”severe internal poisoning caused by inhaling the hairs” Definitions Lepidopterism is the term for cutaneous and systemic reactions that result from contact with larvae (ie, caterpillars) or adult forms of moths and butterflies (order, Lepidoptera). Erucism (from Latin "eruca," caterpillar) is also used to refer to reactions from contact with caterpillars. photo credit: Jon Karnes, MD “The BTM, its caterpillar and their rash” Clinical and Experimental Dermatology (1979), Cicely P. -

Effect of Food Resources on Adult Glyptapanteles Militaris And

PHYSIOLOGICAL ECOLOGY Effect of Food Resources on Adult Glyptapanteles militaris and Meteorus communis (Hymenoptera: Braconidae), Parasitoids of Pseudaletia unipuncta (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae) A. C. COSTAMAGNA AND D. A. LANDIS Department of Entomology, 204 Center for Integrated Plant Systems, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824Ð1311 Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/ee/article/33/2/128/375331 by guest on 29 September 2021 Environ. Entomol. 33(2): 128Ð137 (2004) ABSTRACT Adult parasitoids frequently require access to food and adequate microclimates to maximize host location and parasitization. Realized levels of parasitism in the Þeld can be signiÞcantly inßuenced by the quantity and distribution of extra-host resources. Previous studies have demon- strated a signiÞcant effect of landscape structure on parasitism of the armyworm Pseudaletia unipuncta (Haworth) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae). As a possible mechanism underlying this pattern, we inves- tigated the effect of carbohydrate food sources on the longevity and fecundity of armyworm para- sitoids under laboratory conditions of varying temperature, host availability, and mating status. Glyptapanteles militaris (Walsh) (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) adults lived signiÞcantly longer when provided with honey as food and when reared at 20ЊC versus 25ЊC. Meteorus communis (Cresson) (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) adults also lived signiÞcantly longer when provided with honey, although longevity was reduced when females were provided hosts. Honey-fed females of M. communis parasitized signiÞcantly more hosts because of their increased longevity, but did not differ in daily oviposition from females provided only water. Mating signiÞcantly increased parasitism by honey-fed M. communis, but not those provided water alone. These results indicate that the presence of both carbohydrate resources and moderated microclimates may signiÞcantly increase the life span and parasitism of these parasitoids. -

Implicating an Introduced Generalist Parasitoid in the Invasive Browntail Moth’S Enigmatic Demise

Ecology, 87(10), 2006, pp. 2664–2672 Ó 2006 by the Ecological Society of America IMPLICATING AN INTRODUCED GENERALIST PARASITOID IN THE INVASIVE BROWNTAIL MOTH’S ENIGMATIC DEMISE 1,3 2 1 JOSEPH S. ELKINTON, DYLAN PARRY, AND GEORGE H. BOETTNER 1Department of Plant, Soil and Insect Science and Graduate Program in Organismic and Evolutionary Biology, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Massachusetts 01003 USA 2College of Environmental Science and Forestry, State University of New York, Syracuse, New York 13210 USA Abstract. Recent attention has focused on the harmful effects of introduced biological control agents on nontarget species. The parasitoid Compsilura concinnata is a notable example of such biological control gone wrong. Introduced in 1906 primarily for control of gypsy moth, Lymantria dispar, this tachinid fly now attacks more than 180 species of native Lepidoptera in North America. While it did not prevent outbreaks or spread of gypsy moth, we present reanalyzed historical data and experimental findings suggesting that parasitism by C. concinnata is the cause of the enigmatic near-extirpation of another of North America’s most successful invaders, the browntail moth (Euproctis chrysorrhoea). From a range of ;160 000 km2 a century ago, browntail moth (BTM) populations currently exist only in two spatially restricted coastal enclaves, where they have persisted for decades. We experimentally established BTM populations within this area and found that they were largely free of mortality caused by C. concinnata. Experimental populations of BTM at inland sites outside of the currently occupied coastal enclaves were decimated by C. concinnata, a result consistent with our reanalysis of historical data on C. -

“Thermal Time” Constraints in Papilio: Latitudinal and Local Size Clines Differ in Response to Regional Climate Change

Insects 2014, 5, 199-226; doi:10.3390/insects5010199 OPEN ACCESS insects ISSN 2075-4450 www.mdpi.com/journal/insects/ Article Adaptations to “Thermal Time” Constraints in Papilio: Latitudinal and Local Size Clines Differ in Response to Regional Climate Change J. Mark Scriber *, Ben Elliot, Emily Maher, Molly McGuire and Marjie Niblack Department of Entomology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824, USA; E-Mails: [email protected] (B.E.); [email protected] (E.M.); [email protected] (M.M.); [email protected] (M.N.) * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]. Received: 22 October 2013; in revised form: 20 December 2013 / Accepted: 8 January 2014 / Published: 21 January 2014 Abstract: Adaptations to “thermal time” (=Degree-day) constraints on developmental rates and voltinism for North American tiger swallowtail butterflies involve most life stages, and at higher latitudes include: smaller pupae/adults; larger eggs; oviposition on most nutritious larval host plants; earlier spring adult emergences; faster larval growth and shorter molting durations at lower temperatures. Here we report on forewing sizes through 30 years for both the northern univoltine P. canadensis (with obligate diapause) from the Great Lakes historical hybrid zone northward to central Alaska (65° N latitude), and the multivoltine, P. glaucus from this hybrid zone southward to central Florida (27° N latitude). Despite recent climate warming, no increases in mean forewing lengths of P. glaucus were observed at any major collection location (FL to MI) from the 1980s to 2013 across this long latitudinal transect (which reflects the “converse of Bergmann’s size Rule”, with smaller females at higher latitudes).