April Gifts 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

APRIL GIFTS 2011 Compiled By: Susan F

APRIL GIFTS 2011 Compiled by: Susan F. Glassmeyer Cincinnati, Ohio, 2011 LittlePocketPoetry.Org APRIL GIFTS 2011 1 How Zen Ruins Poets Chase Twitchel 2 Words Can Describe Tim Nolan 3 Adjectives of Order Alexandra Teague 4 Old Men Playing Basketball B.H. Fairchild 5 Healing The Mare Linda McCarriston 6 Practicing To Walk Like A Heron Jack Ridl 7 Sanctuary Jean Valentine 8 To An Athlete Dying Young A.E. Housman 9 The Routine After Forty Jacqueline Berger 10 The Sad Truth About Rilke’s Poems Nick Lantz 11 Wall Christine Garren 12 The Heart Broken Open Ronald Pies, M.D. 13 Survey Ada Jill Schneider 14 The Bear On Main Street Dan Gerber 15 Pray For Peace Ellen Bass 16 April Saturday, 1960 David Huddle 17 For My Father Who Fears I’m Going To Hell Cindy May Murphy 18 Night Journey Theodore Roethke 19 Love Poem With Trash Compactor Andrea Cohen 20 Magic Spell of Rain Ann Blandiana 21 When Lilacs Frank X. Gaspar 22 Burning Monk Shin Yu Pai 23 Mountain Stick Peter VanToorn 24 The Hatching Kate Daniels 25 To My Father’s Business Kenneth Koch 26 The Platypus Speaks Sandra Beasley 27 The Baal Shem Tov Stephen Mitchell 28 A Peasant R.S. Thomas 29 A Green Crab’s Shell Mark Doty 30 Tieh Lien Hua LiChing Chao April Gifts #1—2011 How Zen Ruins Poets I never know exactly where these annual “April Gifts” selections will take us. I start packing my bags in January by preparing an itinerary of 30 poems and mapping out a probable monthlong course. -

Bulletin of the College of William and Mary in Virginia

Vol. 30, No. 4 Bulletin of the College of William and Mary April, 1936 CATALOGUE OF tKtie College of Wiilmm anb iWarp in liTirginia Two Hundred and Forty-Third Year 1935-36 Announcements , Session 1936-37 Williamsburg, Virginia 1936 Entered at the post office at Williamsburg, Virginia, July 3, 1926, under act of August 24, 1912, as second-class matter Issued January, February, March, April, June, August, November Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from LYRASIS IVIembers and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/bulletinofcolleg304coll Wren Building—Front View Showing Lord Botetourt's Statue Vol. 30, No. 4 Bulletin of the College of William and Mary April, 1936 CATALOGUE OF tKfje College of l^illiam anb ifHarp in "Virginia Two Hundred and Forty-Third Year 1935-36 Announcements , Session 1936-37 Williamsburg, Virginia 1936 Entered at the post office at Williamsburg, Virginia, July 3, 1926, under act of August 24, 1912, as second-class matter Issued January, February, March, April, June, August, November CONTENTS Page Calendar 4 College Calendar 5 Board of Visitors 6 Standing Committees of the Board of Visitors 7 Officers of Administration S Officers of Instruction 9 Standing Committees of the Officers of Instruction 16 Alumni Association 18 College Societies and Publications 20 Athletics for Men 22 Athletics for Women 23 Charter of the College 24 History of College 35 Chronological History of the College 38 Priorities 40 Buildings and Grounds 41 Government and Administration 49 Expenses 52 Financial Aid 57 Admission -

Man, Myth, Or Monster

the magazine of the broadSIDE SUMMER 2009 Man, Myth, or Monster A COLLABORATIVE EXHIBITION PRESENTED BY THE LIBRARY OF VIRGINIA AND THE POE MUSEUM, page 2 broadSIDE THE INSIDE STORY the magazine of the LIBRARY OF VIRGINIA Nurture Your Spirit at a Library SUMMER 2009 Take time this summer to relax, recharge, and dream l i b r a r i a n o f v i r g i n i a Sandra G. Treadway hatever happened to the “lazy, hazy, crazy days of l i b r a r y b o a r d c h a i r Wsummer” that Nat King Cole celebrated in song John S. DiYorio when I was growing up? As a child I looked forward to summer with great anticipation because I knew that the e d i t o r i a l b o a r d rhythm of life—for me and everyone else in the world Janice M. Hathcock around me—slowed down. I could count on having plenty Ann E. Henderson of time to do what I wanted, at whatever pace I chose. Gregg D. Kimball It was a heady, exciting feeling—to have days and days Mary Beth McIntire Suzy Szasz Palmer stretched out before me with few obligations or organized activities. I was free to relax, recharge, enjoy, explore, and e d i t o r dream, because that was what summer was all about. Ann E. Henderson My feeling that summer was a special time c o p y e d i t o r continued well into adulthood, then gradually diminished Emily J. -

Art Meets Literature

ART MEETS LITERATURE ART MEETS LITERATURE ART MEETS LITERATURE ART MEETS LITERATURE AN UNDYING LOVE AFFAIR AN UNDYING LOVE AFFAIR AN UNDYING LOVE AFFAIR AN UNDYING LOVE AFFAIR 800 East Broad Street | Richmond, VA 23219 www.lva.virginia.gov 200 N. Boulevard | Richmond, Virginia USA 23220 www.VMFA.museum ART MEETS LITERATURE ART MEETS LITERATURE ART MEETS LITERATURE ART MEETS LITERATURE AN UNDYING LOVE AFFAIR AN UNDYING LOVE AFFAIR AN UNDYING LOVE AFFAIR AN UNDYING LOVE AFFAIR ART MEETS LITERATURE ART MEETS LITERATURE ART MEETS LITERATURE ART MEETS LITERATURE AN UNDYING LOVE AFFAIR AN UNDYING LOVE AFFAIR AN UNDYING LOVE AFFAIR AN UNDYING LOVE AFFAIR This limited-edition publication, created exclusively for the program Art Meets Literature: An Undying Love Affair, features a selection of nine works of art from the collections of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, chosen by the nine museum curators. Each art selection is accompanied by an original poem, written by one of nine award-winning poets. The program Art Meets Literature: An Undying Love Affair was developed to explore the relationship between poetry and the visual arts. The Library of Virginia and the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts are thrilled to welcome the Smithsonian Institution’s ever-popular presenter Dr. Aneta Georgievska-Shine for a magical evening uncovering the “undying love affair” between poetry and master works of art. Art Meets Literature is an event of the Virginia Literary Festival. Anchored by the elegant Library of Virginia Literary Awards Celebration and the popular James River Writers Conference, the Virginia Literary Festival celebrates Virginia’s rich literary resources with a weeklong series of events. -

2015 AWP Conference Schedule

2015 AWP Conference Schedule Wednesday, April 8, 2015 12:00 pm to 7:00 pm W100. Conference Registration Registration Area, Level 1 Attendees who have registered in advance may pick up their registration materials in AWP’s preregistered check-in area, located in the registration area on level 1 of the Minneapolis Convention Center. If you have not yet registered for the conference, please visit the unpaid registration area, also in the registration area on level 1. Please consult the bookfair map in the conference planner for location details. Students must present a valid student ID to check-in or register at our student rate. Seniors must present a valid ID to register at our senior rate. A $50 fee will be charged for all replacement badges. Thursday, April 9, 2015 9:00 am to 10:15 am R117. Literary Production and the Gift Economy Room 211 C&D, Level 2 ( Lisa Bowden, Teresa Carmody, Annie Guthrie) Editors, publishers, writers, and other culture-makers explore the often thorny topic of operating within, and against, the forces of both the market and gift economies at once. How do writers/artists and presenters work best with each other given a touchy cultural playing field where reading fees and literary citizenship are suspect, buying from big boxes online is cheap and easy, reviewers review who they know, and the economic reality of sustaining independent, literary enterprises is costly? 10:30 am to 11:45 am R139. Object and Subject: The Illustrated Book Room 200 F&G, Level 2 (Lincoln Michel, John Woods, Quintan Wikswo, Brad Zellar) “Bring back the illustrated book!” the New Yorker pled last year. -

87Th Annual Conference Schedule FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 13, 2015

87th Annual Conference Schedule FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 13, 2015 (01) FRIDAY 8:30AM – 10:00AM 01-01 LAPSED CATHOLICS IN AMERICAN FICTION Bull Durham A Chair: Jordan Carson, Baylor University ([email protected]) Co-Chair: Ryan Womack, Baylor University ([email protected]) . Prophetic Drama in The Border Trilogy Jay Beavers, Baylor University ([email protected]) . “God don’t lie… and these are His words… He speaks in stones and trees, the bones of things”: Cormac McCarthy and the Iconographic Palimpsest Quinn Tooman, University of North Carolina at Wilmington ([email protected]) . Cormac McCarthy and the Absence of Grace Ryan Womack, Baylor University ([email protected]) . Don DeLillo’s American Religion Jordan Carson, Baylor University ([email protected]) 01-02 ORCHESTRATING AGENCY: IN WHAT WAYS IS OUR PEDAGOGY EVOLVING? Critical Thinking in the Rhet/Comp Classroom Bull Durham B Chair: Kathleen Bell, University of Central Florida ([email protected]) Co-Chair: Steffen Guenzel, University of Central Florida ([email protected]) . Inside the Positioned Voice Lois Markham, Florida Keys Community College ([email protected]) . Student Publications as Sites for Learning about and Testing Rhetorical Agency Deborah Weaver, University of Central Florida ([email protected]) Emily Proulx, University of Central Florida ([email protected]) Matthew Bryan, University of Central Florida ([email protected]) 1 . Transitioning from the Writer as Individual Subject to Networked Agency in Professional Writing Steffen Guenzel, University of Central Florida ([email protected]) 01-03 "TO MAKE YOU HEAR, TO MAKE YOU FEEL... TO MAKE YOU SEE" Joseph Conrad Society of America Crown A Chair: David Mulry, College of Coastal Georgia ([email protected]) Co-Chair: Joseph Lease, Wesleyan College ([email protected]) . -

Pulitzer Prize Winners and Finalists

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

UAA Catalog 2002-03 Pgs 1-464

CATALOG 2002-2003 UNIVERSITY OF ALASKA ANCHORAGE 3211 Providence Drive Anchorage, Alaska 99508-8046 www.uaa.alaska.edu The cover was designed by Gary Adams, University Advancement. Curriculum Manager: Bec Smith Desktop Publishing/Design: Brad Bodde David Woodley Photography Michael Dinneen Proof Reading: Dr. Will Jacobs John Mun Anissa Hauser It is the responsibility of the individual student to become familiar with the policies and regulations of UAA printed in this catalog. The responsibility for meeting all graduation requirements rests with the student. Every effort is made to ensure the accuracy of the information contained in this catalog. However, the University of Alaska Anchorage Catalog is not a contract but rather a guide for the convenience of students. The University reserves the right to change or withdraw courses; to change the fees, rules, and calendar for admission, registration, instruction, and graduation; and to change other regulations affecting the student body at any time. The University of Alaska Anchorage includes the units of Anchorage, Kenai, Kodiak, and Matanuska-Susitna. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. Welcome to UAA.........................................................................9 2. Enrollment Services...................................................................15 3. Tuition, Fees, and Financial Aid..............................................23 4. Advising, Learning, and Assistance .......................................35 5. Student Life ................................................................................41 -

2018-4-Winter-Webedition.Pdf

For more information or to make a gift, please contact us at: JEFFERSONTRUST.ORG Since 2006, The Je erson Trust has provided more than $7 million to support 179 innovative projects at the University of Virginia. CIVIL WARERA CHARLOTTESVILLE The John L. Nau III Center for Civil War History is working on a pair of new digital projects examining the lives of University of Virginia students and African American men from Albemarle County who served in the Union army or navy. Funding from the Je erson Trust helps complete both projects by hiring undergraduate and graduate research assistants, providing necessary research funds, and creating a project website dedicated to telling the stories of UVA Unionists. Jeerson portrait by Thomas Sully, courtesy of Monticello / The Thomas Jeerson Foundation JeffTrustAd_Winter2018.indd 6 11/8/2018 2:10:27 PM SUPPORTING ’HOOS AT EVERY STAGE OF THEIR LIVES Your gift to the Alumni Association Annual Fund supports nearly $2 million in scholarships that we award to promising students each year. Promoting academic excellence is just one way that we serve our alumni and our University. SUPPORT THE UVA ALUMNI ASSOCIATION ANNUAL FUND GiveToHoos.com 180Years_AnnualFundAd_Winter18-FINAL.indd 1 11/7/2018 2:27:01 PM TIMELESS APPEAL OFF GARTH ROAD AND UNDER 8 MINUTES FROM TOWN STRONG VIEWS ON 13 FARMINGTON ACRES IMMACULATE 157 ACRE WESTERN ALBEMARLE ESTATE - EXCELLENT VIEWS 2210 CAMARGO DRIVE $1,250,000 With exceptional curb appeal and premium construction quality in the Meriwether Lewis district, this 5 bedroom, 4.5 bathroom stone and hardiplank residence built in 2007 by Jacques Homes offers an excellent modern floor plan 2155 DOGWOOD LANE • $5,995,000 including 1st floor master, Sited on one of Farmington’s largest, most beautiful open casual living spaces and parcels, ‘Treetops’ is a center hall Georgian constructed in 2001 to uncompromising standards. -

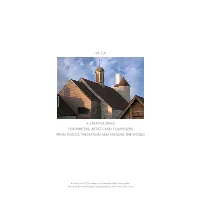

A Creative Space for Writers, Artists and Composers from Across the Nation and Around the World

VCCA A CREATIVE SPACE FOR WRITERS, ARTISTS AND COMPOSERS FROM ACROSS THE NATION AND AROUND THE WORLD Roofline of VCCA studios in a renovated 1930s dairy barn Photo by Bernard Handzel, photographer, New York, New York CONTENTS President’s Report 4 Executive Director’s Report 6 40th Anniversary Celebrations 8 VCCA-France + International 10 Sweet Briar College + VCCA 12 Fellow Stories 13 Composers-in-Residence 14 Artists-in-Residence 16 Writers-in-Residence 20 Cy Twombly and VCCA 24 Suny Monk Fund for Fellows 26 Contributors 28 Government + Foundation Support 38 Financial Information 39 Board of Directors 40 Advisory Council + Fellows Council 41 Senior Staff 43 OPPOSITE PAGE: VCCA Filmmakers Showcase at Mt. San Angelo. The showcase featured a collage of clips from 12 of our filmmaker Fellows. Shown is a frame from “The Weather Inside Us” by Karl Nussbaum Bird by Bryant Holsenbeck, Durham, North Carolina Photo by Karl Nussbaum, filmmaker, New York, New York Photo by Maysey Craddock, artist, Memphis, Tennessee President’s rePort FISCAL YEAR 2011 Fiscal year 2011 was dynamic and was manifest in the visual transformation that took place under transformative for VCCA. The her direction. As international exchanges grew and Fellow challenging economic climate capacity increased, the facilities expanded and improved, and highlighted our strengths: a committed the grounds flourished. Under her leadership, VCCA acquired network of friends, a dedicated Moulin à Nef in Auvillar, France, the jewel in our international board and staff, and a solid 40-year crown. Now in its ninth year, Moulin à Nef continues to grow foundation of serving outstanding as a connection between cultures and communities. -

Contributors, Advertisements

CutBank Volume 1 Issue 69 CutBank 69 Article 30 Summer 2008 Contributors, Advertisements Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cutbank Part of the Creative Writing Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation (2008) "Contributors, Advertisements," CutBank: Vol. 1 : Iss. 69 , Article 30. Available at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cutbank/vol1/iss69/30 This Back Matter is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in CutBank by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. C ontributors GEOFFREY BABBIT is a Ph.D. student in poetry at the University of Utah, where he serves as an associate poetry editorQuarterly for West and Western Humanities Review. His poems have appearedColorado in Review, Interim, Hawaii Review, Confrontation, Pebble Lake Review, West Wind Review, and elsewhere. MATTHEW CLARK teaches and writes in Iowa City. He is working on a series of written portraits that investigate what it means to know someone. A. J. COLLINS recendy completed his first manuscript of poems, graciously supported by the International Institute for Modern Letters. He has taught poetry and composition at the University of California-Irvine, and at the University of Maine-Farmington. He’s currently working on a feature film project in Austin, Texas. In July 2008, he’ll begin development and resource- management projects in South Africa with the Peace Corps. G e o ffre y D e tra n i is a visual artist and writer whose work has been exhibited in New York, Los Angles, and South Korea.