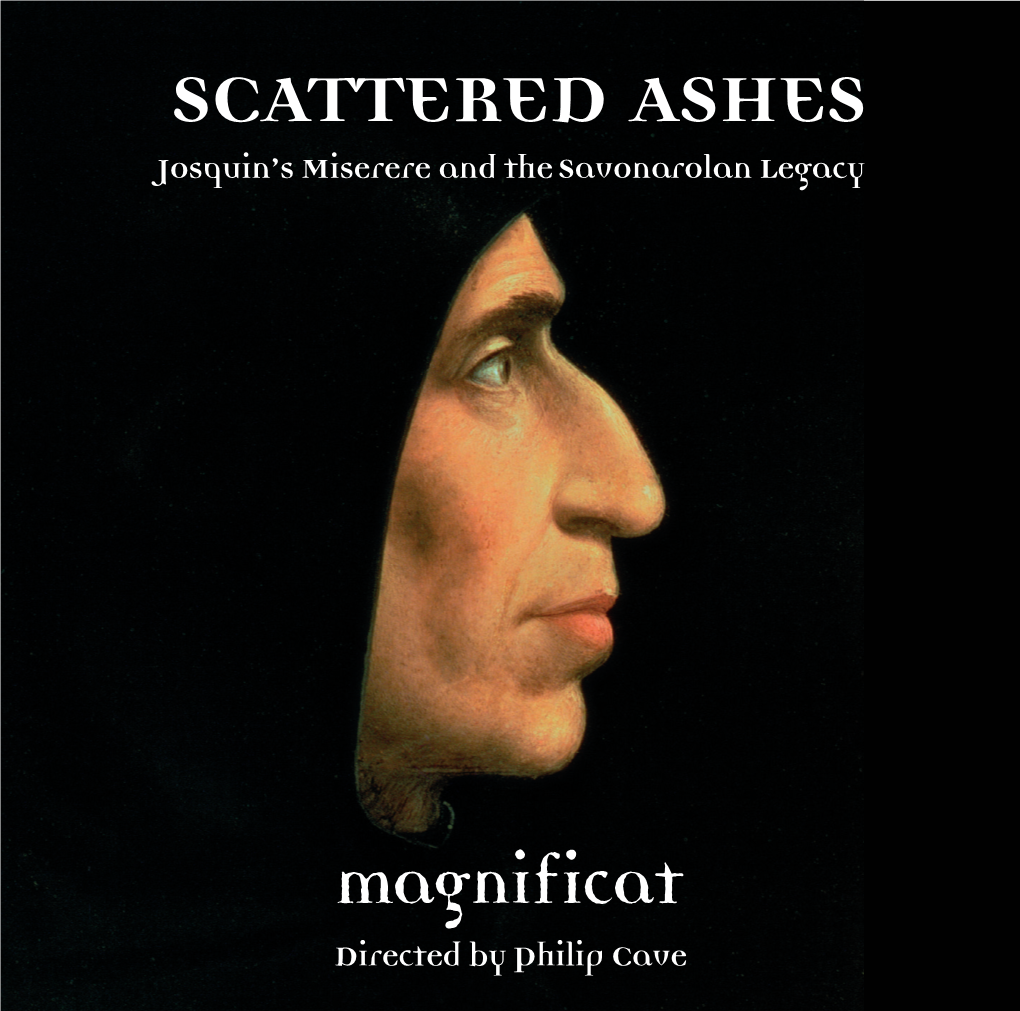

SCATTERED ASHES Josquin’S Miserere and the Savonarolan Legacy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Use of the Simultaneous Cross-Relation by Sixteenth Century English and Continental Composers Tim Montgomery

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Honors Theses Student Research 1968 Use of the simultaneous cross-relation by sixteenth century English and continental composers Tim Montgomery Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Montgomery, Tim, "Use of the simultaneous cross-relation by sixteenth century English and continental composers" (1968). Honors Theses. 1033. https://scholarship.richmond.edu/honors-theses/1033 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. USE OF THE SIMULTANEOUS CROSS-RELATION BY SIXTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH AND CONTINENTAL COMPOSERS Tim Montgomery Music H 391 LmnARY ~tJ=N-IVE-R-·SJTY OF RICHMOND YIRGINIA 2317S The principle of the s~multaneous cross-relation in vocal music has generally and commonly been associated with the English composers of the sixteenth century.(M p.71; R 824 n.J4) This ~ssumption has been more specifically connected with secular music, namely the English madrigal.(Dy p.13) To find the validity of this assumption in relation to both secular and sacred music I have C()mpared the available vocal music of three English composers, two major and one minor: Thomas Tallis (1505-1585), William Byrd (1.543-1623), and Thomas Whythorne (1528-1596). In deciding whether the simultaneous cross-relation was an aspect of English music exclusively, I examined vocal music of three composers of the continent, con temporaries of the English, for the use, if any, of the simul taneous cross-relation. -

Early Fifteenth Century

CONTENTS CHAPTER I ORIENTAL AND GREEK MUSIC Section Item Number Page Number ORIENTAL MUSIC Ι-6 ... 3 Chinese; Japanese; Siamese; Hindu; Arabian; Jewish GREEK MUSIC 7-8 .... 9 Greek; Byzantine CHAPTER II EARLY MEDIEVAL MUSIC (400-1300) LITURGICAL MONOPHONY 9-16 .... 10 Ambrosian Hymns; Ambrosian Chant; Gregorian Chant; Sequences RELIGIOUS AND SECULAR MONOPHONY 17-24 .... 14 Latin Lyrics; Troubadours; Trouvères; Minnesingers; Laude; Can- tigas; English Songs; Mastersingers EARLY POLYPHONY 25-29 .... 21 Parallel Organum; Free Organum; Melismatic Organum; Benedica- mus Domino: Plainsong, Organa, Clausulae, Motets; Organum THIRTEENTH-CENTURY POLYPHONY . 30-39 .... 30 Clausulae; Organum; Motets; Petrus de Cruce; Adam de la Halle; Trope; Conductus THIRTEENTH-CENTURY DANCES 40-41 .... 42 CHAPTER III LATE MEDIEVAL MUSIC (1300-1400) ENGLISH 42 .... 44 Sumer Is Icumen In FRENCH 43-48,56 . 45,60 Roman de Fauvel; Guillaume de Machaut; Jacopin Selesses; Baude Cordier; Guillaume Legrant ITALIAN 49-55,59 · • · 52.63 Jacopo da Bologna; Giovanni da Florentia; Ghirardello da Firenze; Francesco Landini; Johannes Ciconia; Dances χ Section Item Number Page Number ENGLISH 57-58 .... 61 School o£ Worcester; Organ Estampie GERMAN 60 .... 64 Oswald von Wolkenstein CHAPTER IV EARLY FIFTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH 61-64 .... 65 John Dunstable; Lionel Power; Damett FRENCH 65-72 .... 70 Guillaume Dufay; Gilles Binchois; Arnold de Lantins; Hugo de Lantins CHAPTER V LATE FIFTEENTH CENTURY FLEMISH 73-78 .... 76 Johannes Ockeghem; Jacob Obrecht FRENCH 79 .... 83 Loyset Compère GERMAN 80-84 . ... 84 Heinrich Finck; Conrad Paumann; Glogauer Liederbuch; Adam Ile- borgh; Buxheim Organ Book; Leonhard Kleber; Hans Kotter ENGLISH 85-86 .... 89 Song; Robert Cornysh; Cooper CHAPTER VI EARLY SIXTEENTH CENTURY VOCAL COMPOSITIONS 87,89-98 ... -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} Savonarola Ebook Free Download

SAVONAROLA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Elbert Hubbard | 38 pages | 10 Sep 2010 | Kessinger Publishing | 9781169194724 | English | Whitefish MT, United States Savonarola PDF Book Subsequently, Florence was governed along more traditional republican lines, until the return of the Medici in In he became prior of the monastery of San Marco. Character and influence Savonarola's religious actions have been compared to those of the later 17th and 18th century Jansenists, although theologically many differences exist. As the Pope himself frankly confessed, it was the Holy League that insisted. This tense situation came to a head on Palm Sunday, , when a mob comprised of approximately people converged on San Marco, where Savonarola acted as prior. Rather, he wanted to correct the transgressions of worldly popes and secularized members of the Papal Curia. Having made many powerful enemies, the Dominican friar and puritan fanatic Girolamo Savonarola was executed on 23 May That when you were chosen for such a grace: how greatly you are favored to have been made worthy of the blessings and felicity promised to you…. Savonarola ultimately proved unsuccessful in stamping out what had been a longstanding facet of Florentine culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, There he began to preach passionately about the Last Days, accompanied by testimony about his visions and prophetic announcements of direct communications with God and the saints. He drew up letters to the rulers of Christendom urging them to carry out this scheme which, on account of the alliance of the Florentines with Charles VIII, was not altogether beyond possibility. The papal delegates , the general of the Dominicans and the Bishop of Ilerda were sent to Florence to attend the trial. -

Direction 2. Ile Fantaisies

CD I Josquin DESPREZ 1. Nymphes des bois Josquin Desprez 4’46 Vox Luminis Lionel Meunier: direction 2. Ile Fantaisies Josquin Desprez 2’49 Ensemble Leones Baptiste Romain: fiddle Elisabeth Rumsey: viola d’arco Uri Smilansky: viola d’arco Marc Lewon: direction 3. Illibata dei Virgo a 5 Josquin Desprez 8’48 Cappella Pratensis Rebecca Stewart: direction 4. Allégez moy a 6 Josquin Desprez 1’07 5. Faulte d’argent a 5 Josquin Desprez 2’06 Ensemble Clément Janequin Dominique Visse: direction 6. La Spagna Josquin Desprez 2’50 Syntagma Amici Elsa Frank & Jérémie Papasergio: shawms Simen Van Mechelen: trombone Patrick Denecker & Bernhard Stilz: crumhorns 7. El Grillo Josquin Desprez 1’36 Ensemble Clément Janequin Dominique Visse: direction Missa Lesse faire a mi: Josquin Desprez 8. Sanctus 7’22 9. Agnus Dei 4’39 Cappella Pratensis Rebecca Stewart: direction 10. Mille regretz Josquin Desprez 2’03 Vox Luminis Lionel Meunier: direction 11. Mille regretz Luys de Narvaez 2’20 Rolf Lislevand: vihuela 2: © CHRISTOPHORUS, CHR 77348 5 & 7: © HARMONIA MUNDI, HMC 901279 102 ITALY: Secular music (from the Frottole to the Madrigal) 12. Giù per la mala via (Lauda) Anonymous 6’53 EnsembleDaedalus Roberto Festa: direction 13. Spero haver felice (Frottola) Anonymous 2’24 Giovanne tutte siano (Frottola) Vincent Bouchot: baritone Frédéric Martin: lira da braccio 14. Fammi una gratia amore Heinrich Isaac 4’36 15. Donna di dentro Heinrich Isaac 1’49 16. Quis dabit capiti meo aquam? Heinrich Isaac 5’06 Capilla Flamenca Dirk Snellings: direction 17. Cor mio volunturioso (Strambotto) Anonymous 4’50 Ensemble Daedalus Roberto Festa: direction 18. -

A Byrd Celebration

A Byrd Celebration William Byrd 1540–1623 A Byrd Celebration LECTURES AT THE WILLIAM BYRD FESTIVAL EDITED BY RICHARD TURBET CMAA Church Music Association of America Cover picture is of the Lincoln Cathedral, England, where William Byrd was the choirmaster and organ- ist for nine years, 1563–1572. Copyright © 2008 Church Music Association of America Church Music Association of America 12421 New Point Drive Harbor Cove Richmond, Virginia 23233 Fax 240-363-6480 [email protected] website musicasacra.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments . .7 Preface . .9 BIOGRAPHY . .11 William Byrd: A Brief Biography . .13 Kerry McCarthy “Blame Not the Printer”: William Byrd’s Publishing Drive, 1588–1591 . .17 Philip Brett Byrd and Friends . .67 Kerry McCarthy William Byrd, Catholic and Careerist . .75 Joseph Kerman MASSES . .85 The Masses of William Byrd . .87 William Peter Mahrt Byrd’s Masses in Context . .95 David Trendell CANTIONES . .103 Byrd’s Musical Recusancy . .105 David Trendell Grave and Merrie, Major and Minor: Expressive Paradoxes in Byrd’s Cantiones Sacrae, 1589 . .113 William Peter Mahrt Savonarola, Byrd, and Infelix ego . .123 David Trendell William Byrd’s Art of Melody . .131 William Peter Mahrt GRADUALIA . .139 Rose Garlands and Gunpowder: Byrd’s Musical World in 1605 . .141 Kerry McCarthy The Economy of Byrd’s Gradualia . .151 William Peter Mahrt 5 6 — A Byrd Celebration ENGLISH MUSIC . .159 Byrd the Anglican? . .161 David Trendell Byrd’s Great Service: The Jewel in the Crown of Anglican Music . .167 Richard Turbet Context and Meaning in William Byrd’s Consort Songs . .173 David Trendell UNPUBLISHED MOTETS . .177 Byrd’s Unpublished Motets . -

Multiple Choice

Unit 4: Renaissance Practice Test 1. The Renaissance may be described as an age of A. the “rebirth” of human creativity B. curiosity and individualism C. exploration and adventure D. all of the above 2. The dominant intellectual movement of the Renaissance was called A. paganism B. feudalism C. classicism D. humanism 3. The intellectual movement called humanism A. treated the Madonna as a childlike unearthly creature B. focused on human life and its accomplishments C. condemned any remnant of pagan antiquity D. focused on the afterlife in heaven and hell 4. The Renaissance in music occurred between A. 1000 and 1150 B. 1150 and 1450 C. 1450 and 1600 D. 1600 and 1750 5. Which of the following statements is not true of the Renaissance? A. Musical activity gradually shifted from the church to the court. B. The Catholic church was even more powerful in the Renaissance than during the Middle Ages. C. Every educated person was expected to be trained in music. D. Education was considered a status symbol by aristocrats and the upper middle class. 6. Many prominent Renaissance composers, who held important posts all over Europe, came from an area known at that time as A. England B. Spain C. Flanders D. Scandinavia 7. Which of the following statements is not true of Renaissance music? A. The Renaissance period is sometimes called “the golden age” of a cappella choral music because the music did not need instrumental accompaniment. B. The texture of Renaissance music is chiefly polyphonic. C. Instrumental music became more important than vocal music during the Renaissance. -

Les Pseaumes De David (Vol

CONVIVIUMchoir for renaissance·MUSICUM music Scott Metcalfe, music director Les pseaumes de David (vol. II) Les pseaumes mis en rimes francoise, par Clément Marot, & Théodore de Bèze (Geneva, 1562) Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck (1562–1621) Claude Le Jeune (c. 1530–1600) Claude Goudimel (c. 1520–1572) Ps. 114 Quand Israel hors d’Egypte sortit 1. Clément Marot (poem) & Loys Bourgeois (tune), Les pseaumes mis en rimes francoise (Geneva, 1562) 2. Jan Pieterszoon Sweelinck, Livre second des pseaumes de David (Amsterdam, 1613) Ps. 127 On a beau sa maison bâtir 1. Théodore de Bèze (poem) & Loys Bourgeois (tune),Les pseaumes mis en rimes francoise 2. Sweelinck, Livre second des pseaumes de David Ps. 130 Du fonds de ma pensée 1. Marot & Bourgeois, Les pseaumes mis en rimes francoise 2. Claude Goudimel, Les 150 pseaumes de David (Paris, 1564) 3. Goudimel, Les cent cinquante pseaumes de David (Paris, 1568) 4. Sweelinck, Livre second des pseaumes de David Sweelinck: Motets from Cantiones sacrae (Antwerp, 1619) De profundis clamavi (Ps. 130) O domine Jesu Christe Ps. 23 Mon Dieu me paist sous sa puissance haute 1. Marot & Bourgeois, Les pseaumes mis en rimes francoise 2. Claude Le Jeune, Les cent cinquante pseaumes de David (Paris, 1601) 3. Le Jeune, Dodecachorde, contenant douze pseaumes de David (La Rochelle, 1598) intermission Ps. 104 Sus sus, mon ame, il te faut dire bien 1. Marot, Les pseaumes mis en rimes francoise 2. Claude Goudimel, Les 150 pseaumes de David 3. Goudimel, Les cent cinquante pseaumes de David 4. Sweelinck, Livre quatriesme et conclusionnal de pseaumes de David (Haarlem, 1621) Le Jeune: Two psalms from Pseaumes en vers mesurez mis en musique (1606) Ps. -

Album Booklet

Calvin Psalter Calvin Psalter Mon Dieu me paist Verses 1 & 3 harm. Claude Goudimel (c. 1505–1572) harm. Claude Goudimel Psalms by Verse 2 harm. Claude Le Jeune (1528–1600) 14. C’est un Judée (Psalm 76) [0:55] Claude Le Jeune (1528/30–1600) 1. Or sus serviteurs du Seigneur (Psalm 134) [2:20] Claude Le Jeune C’est un Judée (Psalm 76) Calvin Psalter Du dixiesme mode harm. Claude Goudimel 15. C’est un Judée proprement [2:30] 2. Mon Dieu me paist (Psalm 23) [1:10] 16. La void-on par lui fracassez [1:27] The Choir of St Catharine’s College, Cambridge 17. On a pillé comme endormis [1:53] Claude Le Jeune 18. Tu es terrible et plein d’effroi [1:28] Mon Dieu me paist (Psalm 23) 19. Alors ô Dieu! [2:09] Edward Wickham conductor Du quatriesme mode 20. Quelque jour tu viendras trouser [1:58] 3. Mon Dieu me paist [2:21] 21. Offrez vos dons à lui [1:28] 4. Si seurement, que quand au val viendroye [2:57] Calvin Psalter 5. Tu oins mon chef d’huiles [1:46] harm. Claude Goudimel 22. Dés qu’adversité (Psalm 46) [0:59] Calvin Psalter 6. Propos exquis (Psalm 45) [1:01] Claude Le Jeune Dés qu’adversité (Psalm 46) Claude Le Jeune Du neufiesme mode Propos exquis (Psalm 45) 23. Dés qu’adversité nous offense [2:22] Du troisieme mode 24. Voire deusent les eaux profondes [2:00] 7. Propos exquis [2:16] 25. Il est certain qu’au milieu d’elle [2:44] 8. -

The Renaissance Period

The Renaissance Period The Renaissance, which literally means “rebirth” in French, saw movement and change in many different spheres of cultural activity as Europe began to rediscover and identify with its Greco-Roman heritage. The natural sciences (in particular astronomy) began advancing at a rapid pace, and some philosophers began to discuss secular humanism as a valid system. The discovery of the American continents by European navigators resulted in the first widespread speculations of international law and began a crisis of consci ence over human rights that would haunt the West for centuries to come. In particular, however, the Renaissance is remembered for a great a flourishing of the Arts. Secular instrumental music (for early instruments like shawms, crumhorns, and sackbuts) became increasingly popular during this period and composers began to write it down for the first time. The polyphonic madrigal became very popular in England thanks to composers like John Dowland and William Byrd. The motet, a three-part polyphonic composition written for voices or instruments, became popular around this time as well. Despite the increase in secularism, it was still within a religious context that the Renaissance arts truly thrived. Renaissance popes (corrupt as they were) were great patrons of such artists as Michelangelo, Raphael, and Gianlorenzo Bernini. Composers of church music expanded polyphony to six, eight, or even ten interwoven parts. The masses of Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, Tomás Luis de Victoria, and Orlando di Lasso in particular remain some of the most beautiful music ever composed. This polyphonic style was also used by the French composer Josquin des Prez, who wrote both sacred and secular music. -

'The Performing Pitch of William Byrd's Latin Liturgical Polyphony: a Guide

The Performing Pitch of William Byrd’s Latin Liturgical Polyphony: A Guide for Historically Minded Interpreters Andrew Johnstone REA: A Journal of Religion, Education and the Arts, Issue 10, 'Sacred Music', 2016 The choosing of a suitable performing pitch is a task that faces all interpreters of sixteenth- century vocal polyphony. As any choral director with the relevant experience will know, decisions about pitch are inseparable from decisions about programming, since some degree of transposition—be it effected on the printed page or by the mental agility of the singers—is almost invariably required to bring the conventions of Renaissance vocal scoring into alignment with the parameters of the more modern SATB ensemble. To be sure, the problem will always admit the purely pragmatic solution of adopting the pitch that best suits the available voices. Such a solution cannot of itself be to the detriment of a compelling, musicianly interpretation, and precedent for it may be cited in historic accounts of choosing a pitch according to the capabilities of the available bass voices (Ganassi 1542, chapter 11) and transposing polyphony so as to align the tenor part with the octave in which chorale melodies were customarily sung (Burmeister 1606, chapter 8). At the same time, transpositions oriented to the comfort zone of present-day choirs will almost certainly result in sonorities differing appreciably from those the composer had in mind. It is therefore to those interested in this aspect of the composer’s intentions, as well as to those curious about the why and the wherefore of Renaissance notation, that the following observations are offered. -

Image and Influence: the Political Uses of Music at the Court of Elizabeth I

Image and Influence: The Political Uses of Music at the Court of Elizabeth I Katherine Anne Butler Royal Holloway, University of London Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Acknowledgements With thanks to all the people who supported me throughout my research, especially: My supervisor, Stephen Rose, My advisors, Elizabeth Eva Leach and Anna Whitelock, The Arts and Humanities Research Council for funding this research, Royal Holloway Music Department for conference grants, My proofreaders, Holly Winterton, Sarah Beal, Janet McKnight and my Mum, My parents and my fiancé, Chris Wedge, for moral support and encouragement. Declaration of Authorship I, Katherine Butler, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: ______________________ Date: ________________________ 2 Abstract In their Cantiones sacrae (1575), court musicians William Byrd and Thomas Tallis declared that ‘music is indispensable to the state’ (necessarium reipub.). Yet although the relationship between Elizabethan politics and literature has been studied often, there has been little research into the political functions of music. Most accounts of court music consist of documentary research into the personnel, institutions and performance occasions, and generally assume that music’s functions were limited to entertainment and displays of magnificence. However, Elizabethans believed that musical concord promoted a social harmony that would ease the process of government; hence politics and music were seen as closely connected. This thesis is an interdisciplinary investigation into the role of music in constructing royal and courtly identities and influencing Elizabeth’s policies and patronage. -

William Byrd Festival 2008

This book has been published by the Church Music Association of America for distribution at the William Byrd Festival 2008. It is also available for online sales in two editions. Clicking these links will take you to a site from which you can order them. Softcover Hardcover A Byrd Celebration William Byrd 1540–1623 A Byrd Celebration LECTURES AT THE WILLIAM BYRD FESTIVAL EDITED BY RICHARD TURBET CMAA Church Music Association of America Cover picture is of the Lincoln Cathedral, England, where William Byrd was the choirmaster and organ- ist for nine years, 1563–1572. Copyright © 2008 Church Music Association of America Church Music Association of America 12421 New Point Drive Harbor Cove Richmond, Virginia 23233 Fax 240-363-6480 [email protected] website musicasacra.com TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments . .7 Preface . .9 BIOGRAPHY . .11 William Byrd: A Brief Biography . .13 Kerry McCarthy “Blame Not the Printer”: William Byrd’s Publishing Drive, 1588–1591 . .17 Philip Brett Byrd and Friends . .67 Kerry McCarthy William Byrd, Catholic and Careerist . .75 Joseph Kerman MASSES . .85 The Masses of William Byrd . .87 William Peter Mahrt Byrd’s Masses in Context . .95 David Trendell CANTIONES . .103 Byrd’s Musical Recusancy . .105 David Trendell Grave and Merrie, Major and Minor: Expressive Paradoxes in Byrd’s Cantiones Sacrae, 1589 . .113 William Peter Mahrt Savonarola, Byrd, and Infelix ego . .123 David Trendell William Byrd’s Art of Melody . .131 William Peter Mahrt GRADUALIA . .139 Rose Garlands and Gunpowder: Byrd’s Musical World in 1605 . .141 Kerry McCarthy The Economy of Byrd’s Gradualia . .151 William Peter Mahrt 5 6 — A Byrd Celebration ENGLISH MUSIC .