Facilitation for Solar Energy Projects in a Rentier State: Opportunities and Challenges in Oman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study on Renewable Energy Resources, Oman: Final Report

Authority for Electricity Regulation, Oman Study on Renewable Energy Resources, Oman Final Report May 2008 Renewable Energy Resources in Oman Authority for Electricity Regulation, Oman Study on Renewable Energy Resources, Oman Final Report May 2008 COWI and Partners LLC P.O.Box 2115 RUWI Postal Code 112 Sultanate of Oman Tel +968 2460 4200 Fax +968 2460 4788 Report no. 66847-1-1 This report contains the views of the Consultant which do not Issue no. Rev. 0 necessarily correspond to the views of the Authority for Electric- Date of issue 12.05.2008 ity Regulation, Oman. Prepared SEM/NBP/KF/SAJ Checked JHA/DEM Approved SAJ . Page 3 of 134 Renewable Energy Resources in Oman . Page 4 of 134 Renewable Energy Resources in Oman Table of Contents 1 Introduction 8 1.1 Background to the Study 8 1.2 Study Methodology 9 1.3 Collection of data and information 9 1.4 Report Structure 10 1.5 Acknowledgements 10 1.6 Abbreviations and conversion factors 11 2 Executive Summary 13 2.1 Purpose of the Study 13 2.2 Conclusions 14 2.3 Recommendations 24 3 Key information for Oman 31 3.1 Demography 31 3.2 Industry 31 3.3 Electricity sector in Oman 36 3.4 Renewable energy activities in Oman 48 3.5 Conventional energy resources in Oman 48 4 Renewable energy resources in Oman 53 4.1 Wind energy 54 4.2 Solar energy 57 4.3 Biogas 60 4.4 Wave energy 63 4.5 Geothermal energy 64 5 Renewable energy technologies 67 5.1 Wind turbines 67 5.2 Solar PV panels and heaters 72 5.3 Biogas production 83 5.4 Wave energy absorption units 85 5.5 Geothermal power plants 88 5.6 Non energy benefits 90 5.7 Energy efficiency 91 . -

Enchanting Oman: Wadi Shab

al manhal A magazine exploring the oil and gas industry A fount of knowledge Issue two 2014 Enchanting Oman: Wadi Shab 02 10 12 Solar renewable Omani jobs A day in the energy: past, for skilled Omani life of... present and future workers “In a time of increasing importance of the role of media in contemporary life of communities and peoples, it is necessary to work on the development of Omani media, to lead message in the development of the capacity citizen and awareness in turn in the building and his country, and also it contributes to the consolidation of the relations of friendship and cooperation with the international community” His Majesty Sultan Qaboos bin Said Dear Readers, Welcome to issue two of al manhal for 2014. As ever, we have a range of features which we hope will enrich your knowledge about Oman’s oil and gas industry and the important role PDO plays within it. Production Manager a brand new feature series – My Oman – that celebrates the Karima al Shahaibi incomparableTurn to the beauty centre of ourpages country. and you’ll This colourfulalso find addition the first to ofal manhal is produced in association with PDO employee and keen Graphic Design Mohammed al Mahrazi natural wonder to be captured by his lens. photographer Mohammed al Mahrazy, with Wadi Shab the first Design Consultants Our main industry topic this issue looks at the potential for solar United Media Services LLC renewable energy to power the oil and gas sector, spotlighting the successful launch of PDO’s solar steam generation pilot at Amal Translation & Editing and revealing plans for an exciting new solar power project. -

Renewable Energy 2021

Renewable Energy 2021 A practical cross-border insight into renewable energy law First Edition Featuring contributions from: Bracewell (UK) LLP Gómez-Acebo & Pombo Abogados POSSER SPIETH WOLFERS & PARTNERS Cliffe Dekker Hofmeyr Inc (CDH) Gonzalez Calvillo The Law Firm of Wael A. Alissa in Dentons & Co. Jones Day association with Dentons & Co. Doulah & Doulah Mazghouny & Co UMBRA – Strategic Legal Solutions DS Avocats Nishimura & Asahi Wintertons European Investment Bank Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman LLP ISBN 978-1-83918-069-9 ISSN 2634-4300 Published by 59 Tanner Street London SE1 3PL United Kingdom Renewable Energy 2021 +44 207 367 0720 [email protected] www.iclg.com First Edition Consulting Group Publisher Rory Smith Publisher Blanca Alza Reguera Sub Editor Contributing Editor: Matthew Day Mhairi Main Garcia Senior Editor Sam Friend Dentons & Co. Head of Production Suzie Levy Chief Media Officer Fraser Allan CEO Jason Byles Printed by Ashford Colour Press Ltd. Cover image www.istockphoto.com ©2020 Global Legal Group Limited. All rights reserved. Unauthorised reproduction by any means, Strategic Partners digital or analogue, in whole or in part, is strictly forbidden. Disclaimer This publication is for general information purposes only. It does not purport to provide comprehen- sive full legal or other advice. Global Legal Group Ltd. and the contributors accept no responsibility for losses that may arise from reliance upon information contained in this publication. This publication is intended to give an indication of legal issues upon which you may need advice. Full legal advice should be taken from a qualified professional when dealing with specific situations. Table of Contents Expert Chapters Renewable Energy Fuelling a Green Recovery 1 Mhairi Main Garcia, Dentons & Co. -

Integrating Air Quality and Climate Change Strategies in Oman

Integrating air quality and climate change strategies in Oman Jehad Jabr Nasser Albusaidi Doctor of Philosophy University of York Environment September 2019 This thesis is dedicated to my lovely family: my husband Khalid and my children, Tasneem, Elaf, Alwaleed, and Ahmed, for the beauty they bring to my life. For my Oman and its prosperous future. 2 Abstract: Air pollution and climate change are two of the main environmental problems being faced at the moment across the globe and both have a major and costly impact on human health. Oman needs to avoid the negative scenario which could result, and this can best be done by the integration of air quality control and climate change mitigation strategies. This integration would improve air quality and meet climate goals and would be cost-effective as well as beneficial. This thesis investigates the potential for integrated climate and air quality strategies in Oman, and incorporates the mitigation of SLCPs, a group of pollutants that has not yet been considered in the country. The implications of the mitigation strategies on human health and the climate are analysed and the current air quality and climate change policies are examined. The thesis also develops the first emission inventory to be based on national data for the country, using the data for 2010; it presents Oman’s emissions of carbon dioxide, methane, carbon monoxide, sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, non-methane volatile organic compounds, ammonia, particulate matter, black carbon and organic carbon. The emission inventory estimated total emissions of CO2 of 50 Mt, CH4 of 565 kt, SO2 of 160 kt, NMVOCs of 142 kt, NOx of 137 kt, primary PM2.5 of 61 kt, CO of 51 kt, NH3 of 18 kt, BC of 4 kt, and OC of 0.9 kt. -

Oman Energy Master Plan 2040 Three Years on – What’S Happened?

Oman Energy Master Plan 2040 Three Years On – What’s Happened? PR OGRESS REpoRT 2016-2017-2018 Executive Summary: Progress Report 2016-2017-2018 hile the Sultanate of Oman has been able to use petro-dollars to fuel strong development over recent years, its economic and demographic growth is now poised to outstrip resources, posing a complex nexus of W questions about how best to diversify its energy mix, while ensuring energy security and is it possible to do both without liberalizing the economy. There is no doubt Oman faces major energy challenges in the coming decades as conventional fossil fuel resources dwindle and its young population continues to grow rapidly. Inevitably that leaves officials grappling about the long-term viability of the economy and the best energy sources and strategies to meet its needs and drive economic growth. Should Oman pursue clean coal, nuclear power or renewable resources? How important is R&D and the advent of new technology, what about addressing state subsidies that risk the frittering of cheap state energy. We need to ensure that industry-academia-government is adequately aligned to deliver the knowledge and labor force for overcoming tomorrow’s challenges. While there are divergent views on which of these questions are most important, a consensus emerges on the first step to resolving this riddle – that is the need to draft a 25-Year Oman Energy Master Plan. Rising domestic energy demand is presenting the country with a string of challenges and pressure on the Sultanate’s already tight natural gas resources. Oman will have to devise a long-term strategy that considers adding alternative power generation sources such as renewable energies, while also enhancing energy efficiency and improving demand-side management both on an individual and industrial level. -

Renewable Energy in the GCC Countries Resources, Potential, and Prospects

Renewable Energy in the GCC Countries Resources, Potential, and Prospects Renewable Energy in the GCC Countries Resources, Potential, and Prospects Imen Jeridi Bachellerie Gulf Research Center The cover image shows the Beam Down Pilot Project at Masdar City. Photo Credit: Masdar City Gulf Research Center E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.grc.net First published March 2012 Gulf Research Center © Gulf Research Center 2012 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Gulf Research Center. ISBN: 978-9948-490-05-0 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author alone and do not necessarily state or reflect the opinions or position of the Gulf Research Center or the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. By publishing this volume, the Gulf Research Center (GRC) seeks to contribute to the enrichment of the reader’s knowledge out of the Center’s strong conviction that ‘knowledge is for all.’ Dr. Abdulaziz O. Sager Chairman Gulf Research Center About the Gulf Research Center The Gulf Research Center (GRC) is an independent research institute founded in July 2000 by Dr. Abdulaziz Sager, a Saudi businessman, who realized, in a world of rapid political, social and economic change, the importance of pursuing politically neutral and academically sound research about the Gulf region and disseminating the knowledge obtained as widely as possible. The Center is a non-partisan think-tank, education service provider and consultancy specializing in the Gulf region. -

College of Engineering Annual Report 2015 Annual Report Cover May 2016 72497.Indd 2 Sultan Qaboos University

6/9/16 12:12 PM College of Engineering Annual Report 2015 Annual Report cover May 2016 72497.indd 2 Sultan Qaboos University 2015 ANNUAL REPORT COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING College of Engineering Contents 6 College of Engineering 32 Department of Civil and Architectural Engineering 66 Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering 114 Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering 158 Department of Petroleum and Chemical Engineering 3 College of Engineering PUBLICATION AND WEB COMMITTEE «FOCUSING ON PUBLICATIONS OF OUR COLLEGE» Prof. Sabah Ahmed Al-Sulaiman (Chair, Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering) Dr. Abdullah Özer (Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering) Dr. Ashish M. Gujrathi (Department of Petroleum and Chemical Engineering) Dr. Muhammad Bilal Waris (Department of Civil and Architectural Engineering) Dr. Mohammed M. Bait-Suwailam (Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering) Eng. Mohsen Ghanma (Department of Civil and Architectural Engineering) Mr. Ibrahim Mattar Al-Saifi (Assistant Director of Administration, Dean`s Office) 4 Directions by: Prof. Abdullah Hamed Al-Badi (Dean, College of Engineering) Designed by: Athra Hamed Al-Amri (Center for Educational Technology) Photographs by: Mr. Sagharoun Said Al-Hammadi (Center for Educational Technology) Mr. Mohammed Ali Al-Mawali (Center for Educational Technology) Mr. Nabil Humaid Al-Rawahi (Center for Educational Technology) Mr. Yasser Saif Al-Shukaily (Center for Educational Technology) Mr. Issa Salem Al-Fori (Dean`s Office) 5 College of Engineering College of Engineering College of Engineering EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The College of Engineering at Sultan Qaboos University is among the first-ranked Engineering Colleges in GCC and the best Engineering College in Oman. It offers eight internationally accredited undergraduate engineering programs in Architectural, Chemical and Process, Civil, Electrical and Computer, Industrial, Mechanical, Mechatronics, and Petroleum and Natural Gas engineering. -

Assessing the Effectiveness of Solar and Wind Energy in Sultanate of Oman

Journal of Student Research (2017) MEC, Muscat, OMAN Assessing the Effectiveness of Solar and Wind Energy in Sultanate of Oman Mohammed – Hasham Azama, Mohammed F.M. Abushammalaa The Sultanate of Oman is a fast growing region and has fifth largest economy in the GCC regions. The oil and gas sectors are the main promoters of Oman’s economy. The reservoirs of natural resources are insufficient to satisfy for a continuation of the current trends. The electricity sector of Oman mostly depends on natural gas: 97.5% and Diesel: 2.5%. Renewable energy has no major role in the country’s energy supply despite of having valuable wind and solar resources. This review paper tends to bring forward the current and future renewable plans and situations of solar and wind energy in Sultanate of Oman. Therefore this objective is achieved by carrying out literature review of the importance of the wind and solar sources according to the conditions of Oman and by visiting the existing renewable energy plants. Keywords: Energy Sources, Renewable Energy, Solar Energy, Wind Energy. and Water Procurement Company (OPWP) [5], the single buyer Introduction of electricity and water in Oman, peak power demand reached Like rest of the GCC, the Sultanate of Oman has large 4.7gigawatt (GW) in 2013; representing an 89% increase reserves of oil and natural gas which provide a cheaper source compared to 2004, see the figure of power than renewable options made these countries to underutilize [1] the energy renewable resources. Oman is reliant on its oil sector for the majority of its export incomes and government finances. -

Project for Energy Conservation Master Plan in the Power Sector in the Sultanate of Oman

The Sultanate of Oman Public Authority for Electricity and Water Project for Energy Conservation Master Plan in the Power Sector in the Sultanate of Oman Final Report February 2013 Japan International Cooperation Agency Tokyo Electric Power Company IL JR 13-002 Table of Contents Executive Summary Chapter 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background of the Study ......................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Scope and Objective of the Study ............................................................................................ 1 1.2.1 Scope of the Study ............................................................................................................ 1 1.2.2 Objective .......................................................................................................................... 1 1.2.3 Scope of Work .................................................................................................................. 2 1.3 Implementation Schedule ........................................................................................................ 3 1.3.1 Work Flow of the Study .................................................................................................... 3 1.3.2 Work Schedule .................................................................................................................. 5 1.4 Study Team Structure ............................................................................................................. -

Imperial College London a Study of the Challenges and Opportunities To

Imperial College London Faculty of Natural science Centre for Environmental Policy A study of the challenges and opportunities to adopting renewable energy in Oman By Aaisha Al-Sarihi Supervisor: Dr Judith A. Cherni A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy and Diploma of the Imperial College (DIC), in the Centre for Environmental Policy 2018 1 Declaration of Own work I, Aisha Al-Sarihi, declare that this thesis A study of the challenges and opportunities to adopting renewable energy in Oman is entirely my own work and that where any material could be constructed as the work of others, it is fully cited and referenced and/or with appropriate acknowledgement given. Signature: Name of student: Aaisha Al-Sarihi Name of supervisor: Dr Judith A. Cherni 2 Copyright Declaration ‘The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives licence. Researchers are free to copy, distribute or transmit the thesis on the condition that they attribute it, that they do not use it for commercial purposes and that they do not alter, transform or build upon it. For any reuse or redistribution, researchers must make clear to others the licence terms of this work’ 3 Acknowledgements First and foremost, thanks to almighty Allah for giving me wisdom, strength, good health, perseverance and patience to complete the PhD. Thanks to Dr Judith A. Cherni for supervising this PhD. The structure of this thesis would not be the same without her continuous feedback and comments. Thanks for all the intellectual criticism, guidance and support in times of PhD blues. -

Barriers, Risks and Policies for Renewables in the Gulf States

Energies 2015, 8, 8263-8285; doi:10.3390/en8088263 OPEN ACCESS energies ISSN 1996-1073 www.mdpi.com/journal/energies Article Barriers, Risks and Policies for Renewables in the Gulf States Johan Lilliestam †,* and Anthony Patt † Institute for Environmental Decisions, Climate Policy Group, ETH Zürich, Universitätstrasse 22, 8092 Zürich, Switzerland; E-Mail: [email protected] † These authors contributed equally to this work. * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +41-44-632-6037. Academic Editor: Vincenzo Dovì Received: 28 February 2015 / Accepted: 16 July 2015 / Published: 5 August 2015 Abstract: The countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) have both large fossil fuel resources and vast renewable energy potentials. Here, we investigate in a literature meta-analysis and a survey, whether there is a need for renewables in the GCC, what barriers and risks presently deter investments, and what possible policy-solutions could be. We find that there is a long-term need for renewables, to diversify the economy and prepare for a post-fossil fuel era. In the short term, two main obstacles deter investments: inefficient bureaucracy, and the combination of fossil fuel/electricity subsidies and the absence of renewable energy support. Removing fossil fuel and consumption subsidies or introducing a support scheme could make investments in renewables profitable. Eliminating energy subsidies appears particularly beneficial to the economic outlook but this seems particularly difficult to implement, due to the political economy of rentier states. Increased bureaucratic transparency and efficiency is needed, so that potentially attractive investments can rapidly and predictably obtain the necessary permissions. -

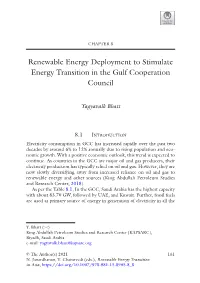

Renewable Energy Deployment to Stimulate Energy Transition in the Gulf Cooperation Council

CHAPTER 8 Renewable Energy Deployment to Stimulate Energy Transition in the Gulf Cooperation Council Yagyavalk Bhatt 8.1 INTRODUCTION Electricity consumption in GCC has increased rapidly over the past two decades by around 6% to 12% annually due to rising population and eco- nomic growth. With a positive economic outlook, this trend is expected to continue. As countries in the GCC are major oil and gas producers, their electricity production has typically relied on oil and gas. However, they are now slowly diversifying away from increased reliance on oil and gas to renewable energy and other sources (King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center, 2018). As per the Table 8.1, In the GCC, Saudi Arabia has the highest capacity with about 83.70 GW, followed by UAE, and Kuwait. Further, fossil fuels are used as primary source of energy in generation of electricity in all the Y. Bhatt (*) King Abdullah Petroleum Studies and Research Center (KAPSARC), Riyadh, Saudi Arabia e-mail: [email protected] © The Author(s) 2021 161 N. Janardhanan, V. Chaturvedi (eds.), Renewable Energy Transition in Asia, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-8905-8_8 162 Y. BHATT Table 8.1 Peak load, available capacity and share of fuel mix in GCC for 2016–2017 Country Available Peak Fuel mix capacity load Gigawatt Gigawatt Natural Crude Heavy fuel Diesel gas oil oil % of fuel mix Year 2016–17 Saudi Arabia 83.7 60.828 45% 23% 24% 8% United Arab 29.06 21 98% 0 2% 0 Emirates Kuwait 18.9 13.39 99.9% 0 0 0 Qatar 10.21 11 100% 0 0 0 Oman 7.8 5.92 97% 0 0 3% Bahrain 4.82 3.418 78% 0 22% 0 Source: Kingdom of Bahrain Electricity & Water Authority, Kuwait Ministry of Electricity & Water, Oman Power and Water Procurement Company, Qatar Electricity & Water Corporation, Electricity & Cogeneration Regulatory Authority, Abu Dhabi Water and Electricity Company, Dubai Electricity and Water Authority, Sharjah Electricity and Water Authority, Federal Energy and Water Authority, KAPSARC data portal GCC countries, primarily natural gas and crude oil and its products.