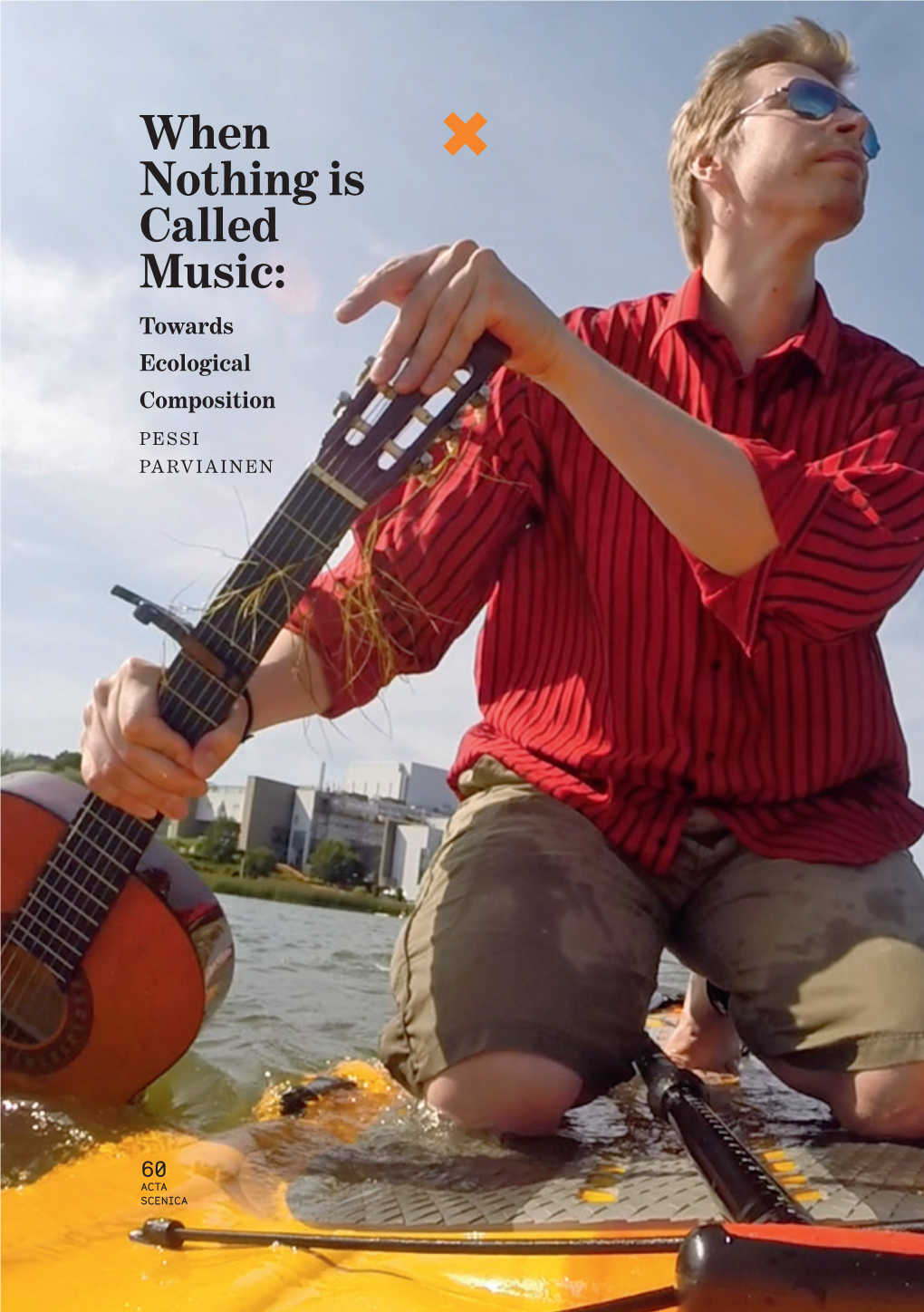

When Nothing Is Called Music: PESSI PARVIAINEN Towards Ecological Composition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P36-40Spe Layout 1

lifestyle THURSDAY, JANUARY 15, 2015 Music & Movies Madonna, AC/DC to play Grammys ceremony op icon Madonna and veteran hard rockers AC/DC The Grammys also tapped heavy metal veterans last will join younger stars in performing at the Grammys year with a performance by Metallica, who played the 25- Pon February 8, organizers of the music industry’s pre- year-old song “One” with classical pianist Lang Lang. mier awards show announced Tuesday. Other musicians Another musician scheduled to play this year’s Grammys is chosen to play at one of the year’s most-watched concerts the country star Eric Church, who is in contention for four include the English singer and songwriter Ed Sheeran, awards. — AFP whose “X” is up for the Grammys’ prestigious Album of the Year, and the child star turned pop singer Ariana Grande, who is nominated in two categories. Madonna, who has won seven Grammys over her three- decade career, is scheduled in March to release a new album, “Rebel Heart,” in which she goes further in a hip- hop direction. She abruptly released six songs from the album in December after versions leaked on the Internet. Madonna, who has a large following in the gay community, also played the Grammys last year in a surprise move, join- ing Macklemore and Ryan Lewis in their same-sex marriage anthem, “Same Love,” as 33 couples of diverse backgrounds got married on the Grammys floor in Los Angeles. AC/DC will take the stage after tumult among the veter- an Australian hard rockers as drummer Phil Rudd faced allegations of hiring a hitman in New Zealand and found- ing member Malcolm Young retired to a special care home as he suffers dementia. -

Garth Brooks. the Life of Chris Gaines Free Download Garth Brooks

garth brooks. the life of chris gaines free download Garth brooks. the life of chris gaines free download. Our systems have detected unusual traffic activity from your network. Please complete this reCAPTCHA to demonstrate that it's you making the requests and not a robot. If you are having trouble seeing or completing this challenge, this page may help. If you continue to experience issues, you can contact JSTOR support. Block Reference: #44e3ed50-f665-11eb-94e5-7912fe89ce48 VID: #(null) IP: 188.246.226.140 Date and time: Fri, 06 Aug 2021 03:20:37 GMT. The Untold Truth Of Chris Gaines. In 1999, Garth Brooks was on top of the country music world. He decided to tackle rock next—but rather than just release a Garth Brooks rock album, he created an elaborate character named Chris Gaines. Sporting a soul patch and a long black wig, "Chris Gaines" was envisioned as the Ziggy Stardust to Brooks' David Bowie. In reality, he became the biggest embarrassment of Brooks' career. Here's a look at one of the weirdest episodes in music history. Gaines' only album was a "greatest hits" compilation. Garth Brooks didn't simply put out Chris Gaines' purported debut album—he released a Gaines greatest hits compilation. If it wasn't already confusing enough for fans wondering why Brooks was dressed like a goth teenager, he made it worse by pretending that people were supposed to have already heard of his alter ego. Creatively titled Chris Gaines' Greatest Hits , the album was supposedly the highlights of highly successful solo albums like Gaines' "debut," Straight Jacket , whose cover featured Gaines pictured in a straightjacket—flanked by naughty nurses, as is a rock star's wont. -

Aave- Alternative Audiovisual Event 11.–17.4.2016 Helsinki Aave- Alternative Audiovisual Event Festivaaliohjelmisto / Festival Program 11.–17.4.2016 Helsinki

AAVE- ALTERNATIVE AUDIOVISUAL EVENT 11.–17.4.2016 HELSINKI AAVE- ALTERNATIVE AUDIOVISUAL EVENT FESTIVAALIOHJELMISTO / FESTIVAL PROGRAM 11.–17.4.2016 HELSINKI LAUANTAI / SATURDAY 9.4.2016 FESTIVAALIOHJELMISTO / FESTIVAL PROGRAM 3 18:00–00:00 PRE-FESTIVAL EVENT / Night of the Beamers [PU] ESITTELY / INTRODUCTION 4 KALENTERI / TIMETABLE 6 KESKIVIIKKO / WEDNESDAY 13.4.2016 18:00–22:00 FESTIVAL WARM-UP / Andre Vicentini & Fernando Visockis: Conducting Senses [VT] (A) NIGHT OF THE BEAMERS 8 LÄMMITTELYTAPAHTUMA / WARM-UP EVENT 9 TORSTAI / THURSDAY 14.4.2016 OISHII! 10 18:00 FESTIVAL OPENING [MA] 18:30 OISHII / Shindō Kaneto: Naked Island [MA] LIVE CINEMA 14 20:30 LIVE CINEMA / Cine Fantom & Koelse: Jevgeni Kontradiev [MA] EN GARDE 21 KROKI 28 PERJANTAI / FRIDAY 15.4.2016 11:00–15:00 SEMINAR / Lenka Kabankova, Gleb Aleynikov, Anka & Wilhelm Sasnal [W] (A) CINE FANTOM 32 17:30 OISHII / Itami Jūzō: Tampopo [MA] KULJUNTAUSTA & VAN INGEN IN TANDEM 37 19:45 KROKI / Maciej Sobieszczański & Łukasz Ronduda: The Performer [MA] YLEN AVARUUSROMUA 25V. 41 21:00 LIVE CINEMA / Kuukka, Kuukka & Luukkonen: Taking Pictures [MA] 22:30 YLE AVARUUSROMUA 25V. / Rauli Valo &Jukka Mikkola + Random Doctors & Klaustrofobia [PO] NÄYTTELYT / EXHIBITIONS 42 SEMINAARI / SEMINAR 46 LAUANTAI / SATURDAY 16.4.2016 JÄRJESTÄJÄT / ORGANISERS 47 14:00 EN GARDE / Ghost Lights ’16: Matter, Memory and Midsummer [MA] (A) 15:00 KROKI / Anka & Wilhelm Sasnal: Parasite [MA] (A) YHTEISTYÖKUMPPANIT / COLLABORATORS 47 16:30 EN GARDE / Roee Rosen [MA] (A) 18:00 LIVE CINEMA / Destroyer2048: -

Helsinki in Early Twentieth-Century Literature Urban Experiences in Finnish Prose Fiction 1890–1940

lieven ameel Helsinki in Early Twentieth-Century Literature Urban Experiences in Finnish Prose Fiction 1890–1940 Studia Fennica Litteraria The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. Two additional subseries were formed in 2002, Historica and Litteraria. The subseries Anthropologica was formed in 2007. In addition to its publishing activities, the Finnish Literature Society maintains research activities and infrastructures, an archive containing folklore and literary collections, a research library and promotes Finnish literature abroad. Studia fennica editorial board Pasi Ihalainen, Professor, University of Jyväskylä, Finland Timo Kaartinen, Title of Docent, Lecturer, University of Helsinki, Finland Taru Nordlund, Title of Docent, Lecturer, University of Helsinki, Finland Riikka Rossi, Title of Docent, Researcher, University of Helsinki, Finland Katriina Siivonen, Substitute Professor, University of Helsinki, Finland Lotte Tarkka, Professor, University of Helsinki, Finland Tuomas M. S. Lehtonen, Secretary General, Dr. Phil., Finnish Literature Society, Finland Tero Norkola, Publishing Director, Finnish Literature Society Maija Hakala, Secretary of the Board, Finnish Literature Society, Finland Editorial Office SKS P.O. Box 259 FI-00171 Helsinki www.finlit.fi Lieven Ameel Helsinki in Early Twentieth- Century Literature Urban Experiences in Finnish Prose Fiction 1890–1940 Finnish Literature Society · SKS · Helsinki Studia Fennica Litteraria 8 The publication has undergone a peer review. The open access publication of this volume has received part funding via a Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation grant. -

Helsinki Scurt Istoric

23-29 aprilie 2017 Finlanda – o ţară a contrastelor Aurora Boreala ȚARA CELOR 1000 DE LACURI Helsinki Scurt istoric • Până în 1809 Finlanda a constituit o provincie estică a Suediei. • Ulterior devine Mare Ducat Autonom, în cadrul Imperiului Rus. • Abia în 6 decembrie 1917 îşi proclamă independenţa, dupa 108 ani de dominaţie rusească şi alti 600 ca parte integrantă a Suediei. 100 de ani de la proclamarea independenţei - termen finlandez care poate fi tradus ca forță a voinței, hotărârii, perseverenței și acțiunii raționale în fața adversității Introducere în programul cursului Informaţii despre English Matters - 23 aprilie 2017 - Participanţi din 17 ţări europene Germania Slovenia Franţa Luxemburg Spania Romania Italia Georgia Belgia Luxemburg Irlanda Polonia Grecia Cehia Slovacia Materiale pentru curs 24 aprilie 2017 • Tur al oraşului „Welcome to Finland! - Helsinki” • Istorie, cultură şi civilizaţie • Seminar la Universitatea din Helsinki – Anna Ikonnen – Sistemul Educaţional Finlandez Întâlnire în Piaţa Senatului Senate Square Piaţa Senatului – Senate Square Catedrala din Helsinki – Helsinki Cathedral Țarul Alexandru al II- lea Temppeliaukio Church - Rock Church Temppeliaukio Church - Rock Church interior Temppeliaukio Church - Rock Church cupola interioară Ateneul – Ateneum Art Museum Campusul universitar – City Center Campus Biblioteca Universităţii din Helsinki Catedrala Uspensky Biserica germană - German Church Clădirea Guvernului Palatul Prezidenţial National Library Muzeul National - National Museum Muzeul de artă contemporană -

See Helsinki on Foot 7 Walking Routes Around Town

Get to know the city on foot! Clear maps with description of the attraction See Helsinki on foot 7 walking routes around town 1 See Helsinki on foot 7 walking routes around town 6 Throughout its 450-year history, Helsinki has that allow you to discover historical and contemporary Helsinki with plenty to see along the way: architecture 3 swung between the currents of Eastern and Western influences. The colourful layers of the old and new, museums and exhibitions, large depart- past and the impact of different periods can be ment stores and tiny specialist boutiques, monuments seen in the city’s architecture, culinary culture and sculptures, and much more. The routes pass through and event offerings. Today Helsinki is a modern leafy parks to vantage points for taking in the city’s European city of culture that is famous especial- street life or admiring the beautiful seascape. Helsinki’s ly for its design and high technology. Music and historical sights serve as reminders of events that have fashion have also put Finland’s capital city on the influenced the entire course of Finnish history. world map. Traffic in Helsinki is still relatively uncongested, allow- Helsinki has witnessed many changes since it was found- ing you to stroll peacefully even through the city cen- ed by Swedish King Gustavus Vasa at the mouth of the tre. Walk leisurely through the park around Töölönlahti Vantaa River in 1550. The centre of Helsinki was moved Bay, or travel back in time to the former working class to its current location by the sea around a hundred years district of Kallio. -

In This Issue

04 helen 2013 English Newsletter | www.helen.fi in this issue 01 ENERGy fROm aN UNDERGROUND NETWORK 02 YOu aRE IMPORTANt to uS 03 TOWARDS a sMARt hOME 04 NEWS ENERGY 01 from an underground network The city centre of Helsinki Markus Parviainen, Investment Mana- erties in the city centre of Helsinki and ger at Helen Sähköverkko Oy, is becko- taken into use in 2011. has often been called ‘cheese ning us at the roundabout to follow his The substation is located at the cen- with holes’. Its most important estate car. In just a moment, we arri- tre of the greatest load density in Fin- ve at the crossroad of Aleksanterinkatu land’s electricity use, and its output is con- holes are the energy tunnels and Mannerheimintie – albeit 30 metres sumed already within the area of about that contribute to the security underground. one square kilometre. The Kluuvi substation is located al- – Consumption of a hundred mega- of energy supply in the capital. most directly beneath the Three Smiths watts per one square kilometre is quite Statue. It was excavated in connection unique in the Finnish conditions, Parviainen Pertti Suvanto | PHOTOS Pekka Nieminen with the service tunnel serving the prop- points out. continues on page 2 © Helsingin Energia from previous page Crisscrossing and overlapping network There is a simple reason for having the net- work underground: there is no free land left to build on in the most efficient and densely built areas in Helsinki. – Here, we are in the middle of the city and still out of sight. -

Titles Earned January 1 - December 31, 2018 Compiled by Laura Wright

Titles Earned January 1 - December 31, 2018 Compiled by Laura Wright. Please send corrections/omissions to [email protected] Agility Course Test 1 Seven Marshall-Enrietlo NA ACT1 Panacea's Crazy Not To Have An Alibi RN JH ACT2 TKP Shine's Bright Like A Diamond NA Rheingold Froh Guinness For Strength ACT1 Skipfire's One And Only Gibbs NA Seven Marshall-Enrietlo ACT1 CH Szikra Bit O Honey At Firestorm NA NF Sincerus Je's Everglow What A Wonderful World ACT1 CH Topaz's Classic Andre CD BN RA JH NA THDN CGC TKA Venari's Crimson Gem NA NF Agility Course Test 2 Whimzi's Mountain Pride Crimson Glory NA CGCA TKN Barben's Boom Boom Syrah ACT2 Xtra Point Benelli Black Eagle NA Legacy's Scarlet Begonia ACT2 Zola Hathor NA NAJ NF Panacea's Crazy Not To Have An Alibi RN JH ACT2 TKP Pinewoods Perfect Whiskey Manhattan CD PCD BN RN Novice Agility Preferred ACT2 CGCA CGCU TKI GCHS CH Aislinn's RR Elite Edition JH NAP NJP CA CGCA CH River Run's It's A Sweet Sweet Life JH ACT2 CGCA CGCU TKA GCH CH Firelight's First Lady Liesl RA NAP NJP CGC Novice Agility Pinewoods Perfect Whiskey Manhattan CD PCD BN RI Barkley Young NA NAP ACT2 SIN CGCA CGCU TKI GCHB CH Cruiser's All The Right Moves BN RN MH NA CA GCH CH Priden Joy Mighty Joe PCD BN RE NAP NJP NFP Derby's New Girl In Town At Windswept Acre's NA Rockwoods Give 'Em 'El Hobbes NAP NJP Desert Sunset Saige Of Faha Farms NA CH Sommer's Captain Morgan CD BN RAE JH NAP NJP Dorratz Edenvale Stars Align NA CAA BCAT RATN CGC Dorratz Koppertone Dreams Come True JH NA NAJ GCHP CH Szizlin Rhapsody Never Say Never -

À the Dark Knight Rises (2012) Jérôme Rossi

Document généré le 25 sept. 2021 12:01 Revue musicale OICRM Essai de caractérisation de l’évolution des musiques super-héroïques de Batman (1989) à The Dark Knight Rises (2012) Jérôme Rossi Création musicale et sonore dans les blockbusters de Remote Control Résumé de l'article Volume 5, numéro 2, 2018 Vingt-trois années séparent les musiques des films Batman (Tim Burton, 1989) et The Dark Knight Rises (Christopher Nolan, 2012) avec les compositions URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1054146ar respectives de Danny Elfman et Hans Zimmer. Si les compositeurs restent tous DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1054146ar deux fidèles à une conception signalétique des thèmes, Zimmer propose toutefois un nombre plus élevé de matériaux thématiques, avec la présence Aller au sommaire du numéro d’un « ostinato identifiant » pour chacun des trois personnages principaux, en plus de leurs thèmes propres. Élaborée par une véritable équipe, la « narration sonore » constitue également un enjeu majeur de l’esthétique de Nolan et Zimmer avec l’élaboration, sur Éditeur(s) l’ensemble du film, d’un continuum bruit/musique, dont ce que nous avons Observatoire interdisciplinaire de création et recherche en musique (OICRM) appelé l’« effects underscoring » constitue l’une des stratégies les plus novatrices parmi celles proposées. L’« effects underscoring » est une technique ISSN compositionnelle par laquelle la musique se voit destinée à former un écrin émotionnel non plus aux voix, mais aux bruits lors de séquences où ce sont eux 2368-7061 (numérique) qui, par leur -

Contemporary Film Music

Edited by LINDSAY COLEMAN & JOAKIM TILLMAN CONTEMPORARY FILM MUSIC INVESTIGATING CINEMA NARRATIVES AND COMPOSITION Contemporary Film Music Lindsay Coleman • Joakim Tillman Editors Contemporary Film Music Investigating Cinema Narratives and Composition Editors Lindsay Coleman Joakim Tillman Melbourne, Australia Stockholm, Sweden ISBN 978-1-137-57374-2 ISBN 978-1-137-57375-9 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-57375-9 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017931555 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017 The author(s) has/have asserted their right(s) to be identified as the author(s) of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

Leonardo Dicaprio Ing a Break from Her Wonder Woman “Sexual Content, Action/Violence and Brief Duties)

lifestyle THURSDAY, OCTOBER 20, 2016 MUSIC & MOVIES Hundreds mourn top filmmaker Andrzej Wajda in Poland undreds of people mourning for Poland’s leading film- maker Andrzej Wajda are paying their respect by pass- Hing in silence before an urn with Wajda’s ashes at a church in southern Poland ahead of his funeral. Poland’s President Andrzej Duda, foreign diplomats, actors and intel- lectuals attended the funeral Mass at the Dominican friars’ church in Krakow. Later Wajda will be laid to rest at the city’s historic Salwator Cemetery, where the movie director’s moth- er is buried. Wajda died in a Warsaw hospital Oct 9 at the age of 90, just months after finishing “Afterimage,” Poland’s entry for a for- eign language Academy Award. In 2000 he received an hon- orary lifetime achievement Oscar. On Tuesday, hundreds of people in Warsaw, where he lived, bid Wajda farewell in a spe- cial Mass. — AP The urn with the ashes of Poland People pay their respects to late Polish filmmaker Andrzej Wajda attend a mourning filmmaker Andrzej Wajda is set out Mass, in Krakow, Poland yesterday. — AP photos during a farewell ceremony. Michael Jordan’s ‘Space Jam’ Review returning to theaters ‘The Joneses’ is another ichael Jordan, Bugs Bunny Fathom Events and Warner Bros. and friends are returning to say the screenings will take place on Mthe court, and theaters, to Sunday, Nov 13, and Wednesday, Nov mark the 20th anniversary of “Space 16. Basketball greats Larry Bird, studio comedy misfire Jam.” The 1996 basketball-themed Charles Barkley and Patrick Ewing adventure, which combined the real also appear in the film, as does Bill life Jordan with animated Looney Murray, who joins with Jordan to he modern studio comedy increas- But what makes the Joneses most jeal- Tunes characters, will be back on defeat a team of aliens. -

Uma Perspectiva Musicológica Sobre a Formação Da Categoria Ciberpunk Na Música Para Audiovisuais – Entre 1982 E 2017

Uma perspectiva musicológica sobre a formação da categoria ciberpunk na música para audiovisuais – entre 1982 e 2017 André Filipe Cecília Malhado Dissertação de Mestrado em Ciências Musicais Área de especialização em Musicologia Histórica Setembro de 2019 I Dissertação apresentada para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Ciências Musicais – Área de especialização em Musicologia Histórica, realizada sob a orientação científica da Professora Doutora Paula Gomes Ribeiro. II Às duas mulheres da minha vida que permanecem no ciberespaço do meu pensamento: Sara e Maria de Lourdes E aos dois homens da minha vida com quem conecto no meu quotidiano: Joaquim e Ricardo III Agradecimentos Mesmo tratando-se de um estudo de musicologia histórica, é preciso destacar que o meu objecto, problemática, e uma componente muito substancial do método foram direccionados para a sociologia. Por essa razão, o tema desta dissertação só foi possível porque o fenómeno social da música ciberpunk resulta do esforço colectivo dos participantes dentro da cultura, e é para eles que direciono o meu primeiro grande agradecimento. Sinto-me grato a todos os fãs do ciberpunk por manterem viva esta cultura, e por construírem à qual também pertenço, e espero, enquanto aca-fã, ter sido capaz de fazer jus à sua importância e aos discursos dos seus intervenientes. Um enorme “obrigado” à Professora Paula Gomes Ribeiro pela sua orientação, e por me ter fornecido perspectivas, ideias, conselhos, contrapontos teóricos, ajuda na resolução de contradições, e pelos seus olhos de revisora-falcão que não deixam escapar nada! Como é evidente, o seu contributo ultrapassa em muito os meandros desta investigação, pois não posso esquecer tudo aquilo que me ensinou desde o primeiro ano da Licenciatura.