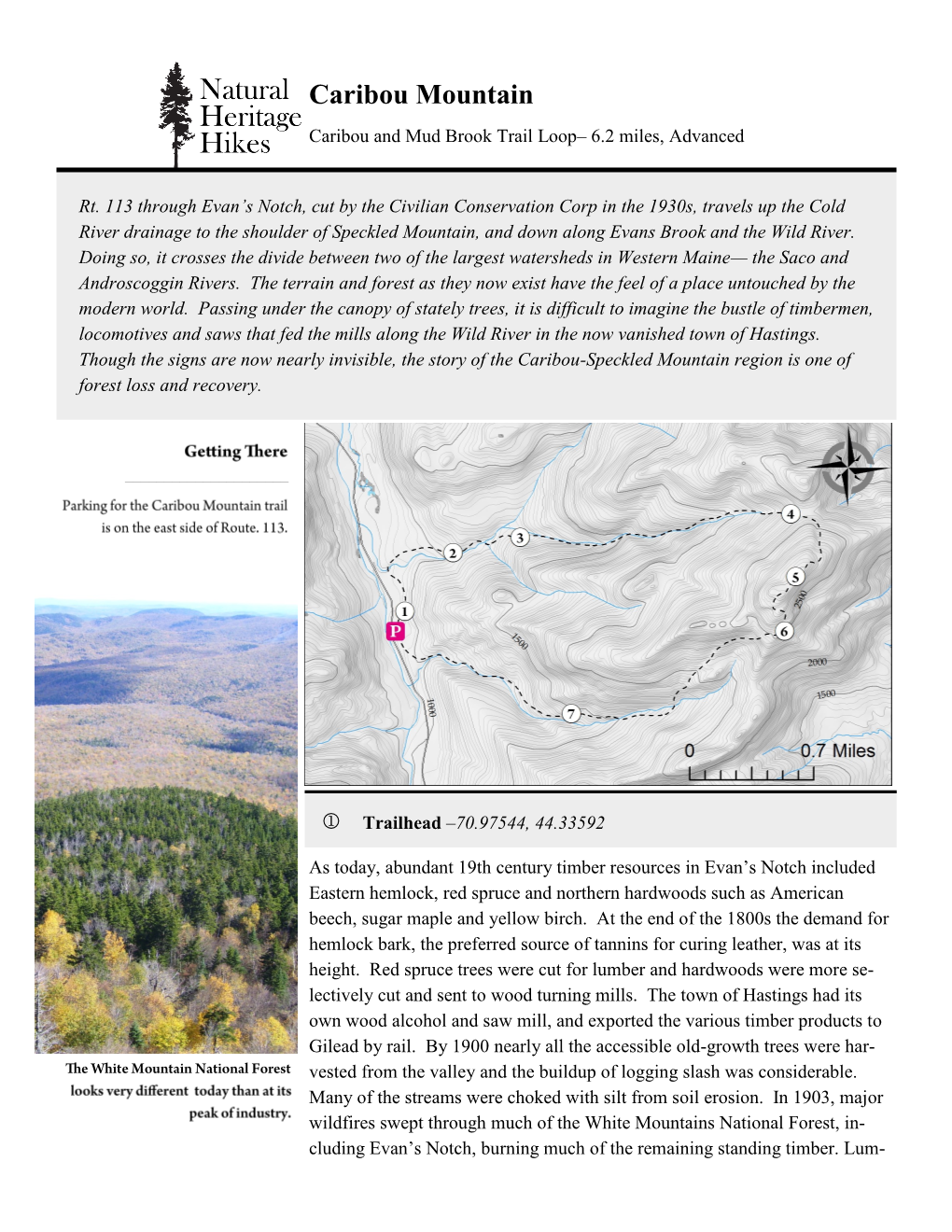

Caribou Mountain Caribou and Mud Brook Trail Loop– 6.2 Miles, Advanced

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Areas of the National Forest System

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2018 Forest Service WO Lands FS-383 November 2018 United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS-383 System November 2018 As of September 30, 2018 Published by: USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, D.C. 20250-0003 Web site: https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar-index.shtml Cover photo courtesy of: Chris Chavez Statistics are current as of: 10/15/2018 The National Forest System (NFS) is comprised of: 154 National Forests 58 Purchase Units 20 National Grasslands 7 Land Utilization Projects 17 Research and Experimental Areas 28 Other Areas NFS lands are found in 43 States as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. TOTAL NFS ACRES = 192,948,059 NFS lands are organized into: 9 Forest Service Regions 112 Administrative Forest or Forest-level units 506 Ranger District or District-level units The Forest Service administers 128 Wild and Scenic Rivers in 23 States and 446 National Wilderness Areas in 39 States. The FS also administers several other types of nationally-designated areas: 1 National Historic Area in 1 State 1 National Scenic Research Area in 1 State 1 Scenic Recreation Area in 1 State 1 Scenic Wildlife Area in 1 State 2 National Botanical Areas in 1 State 2 National Volcanic Monument Areas in 2 States 2 Recreation Management Areas in 2 States 6 National Protection Areas in 3 States 8 National Scenic Areas in 6 States 12 National Monument Areas in 6 States 12 Special Management Areas in 5 States 21 National Game Refuge or Wildlife Preserves in 12 States 22 National Recreation Areas in 20 States Table of Contents Acreage Calculation ........................................................................................................... -

SMPDC Region

Southern Maine Regional Planning Commission Region Shelburne Batchelders Grant Twp Woodstock Sumner Hartford Mason Twp Beans Purchase Greenwood West Paris Miles Knob !! Miles Notch Number Eight Pond ! Albany Twp Shirley Brook ! Speckled Mountain ! Red Rock Brook Pine Mountain ! ! Lombard Pond ! Isaiah Mountain 3 ! 1 1 Hannah Brook E ! ! Ha T Stoneham ! y R R Sugarloaf Mountain d Willard Brook ! Goodwin Brook T Sugarloaf Mountain S ! B W Virginia Lake in Basin Brook ir Buckfield Brickett Place ! c B ! ! H h ! ro u Cecil Mountain w t A n R ! v R Bickford Brook d Co d d ld ! ! R Bro ok T rl B k Bartlett Brook o d a o R ! n r llen u C G B Beaver Brook ! d r r Mason Hill o Palmer Mountain M d o ! v f o d ! e u R k R r S n r c d i to t n a R e H A ld e R B o in u d k se Rattlesnake Mountain e d r i r Rd ! R Little Pond a f e a t d d m W e ! tl is R B l d t d s i d l n S L R A R l Rattlesnake Brook R n R il M A c ! I t ! a ! o B H in s ! d rs l e n e n r ! e l M S i a t e t d t Adams Mountain id e d u Shell Pond u l B n o l d h e Harding Hill o S o ! a y R R P G m d W d Stiles Mountain d d Great B!rook o Pine Hill R ! n n R ! R d ! y o n ! lle P Pine Hill d R a ee Cold B!rook d Pike's Peak V ll K n e c ! Foster Hill Little Deer HillDeer Hill ee h M Birch Island ! ! ! ! r S ! rg oe Mud Pond Upper Bay ve J Bradley Pond E ! Sheep Islan!d A ! ! nd Amos Mountain C Allen Mountain Paris re ! us ! n w Flat Hill h Rattlesnake Island L s m L ! Deer Hill Spring Harndon Hill Horseshoe Pond r n a Trout Pond ! ! ! e n W d P ! lm o ! Weymouth HillWeymouth -

Speckled Mountain Heritage Hikes Bickford Brook and Blueberry Ridge Trails – 8.2-Mile Loop, Strenuous

Natural Speckled Mountain Heritage Hikes Bickford Brook and Blueberry Ridge Trails – 8.2-mile loop, strenuous n the flanks and summit of Speckled Mountain, human and natural history mingle. An old farm Oroad meets a fire tower access path to lead you through a menagerie of plants, animals, and natural communities. On the way down Blueberry Ridge, 0with0.2 a sea 0.4 of blueberry 0.8 bushes 1.2 at 1.6 your feet and spectacular views around every bend, the rewards of the summit seem endless. Miles Getting There Click numbers to jump to descriptions. From US Route 2 in Gilead, travel south on Maine State Route 113 for 10 miles to the parking area at Brickett Place on the east side of the road. From US Route 302 in Fryeburg, travel north on Maine State Route 113 for 19 miles to Brickett Place. 00.2 0.4 0.8 1.2 1.6 Miles A House of Many Names -71.003608, 44.267292 Begin your hike at Brickett Place Farm. In the 1830s, a century before present-day Route 113 sliced through Evans Notch, John Brickett and Catherine (Whitaker) Brickett built this farmhouse from home- made bricks. Here, they raised nine children alongside sheep, pigs, cattle, and chick- ens. Since its acquisition by the White Mountain National Forest in 1918, Brickett Place Farmhouse has served as Civilian Conservation Corps headquarters (1930s), Cold River Ranger Station (1940s), an Appalachian Mountain Club Hut (1950s), and a Boy Scouts of America camp (1960-1993). Today, Brickett Place Farmhouse has gone through a thorough restoration and re- mains the oldest structure in the eastern region of the Forest Service. -

Timeline of Maine Skiing New England Ski Museum in Preparation for 2015 Annual Exhibit

Timeline of Maine Skiing New England Ski Museum In preparation for 2015 Annual Exhibit Mid 1800s: “…the Maine legislature sought to populate the vast forests of northern Maine. It offered free land to anyone who would take up the challenge of homesteading in this wilderness. ...Widgery Thomas, state legislator and ex-Ambassador to Sweden…suggested that the offer of free land be made to people in Sweden. In May, 1870 Thomas sailed for Sweden to offer 100 acres of land to any Swede willing to settle in Maine. Certificates of character were required. Thomas himself had to approve each recruit.” Glenn Parkinson, First Tracks: Stories from Maine’s Skiing Heritage . (Portland: Ski Maine, 1995), 4. March 1869: “In March 1869 the state resolved “to promote the settlement of the public and other lands” by appointing three commissioners of settlement. William Widgery Thomas, Jr., one of the commissioners, had extensive diplomatic experience as ambassador to Sweden for Presidents Arthur and Harrison. Thomas had lived among the Swedes for years and was impressed with their hardy quality. He returned to the United States convinced that Swedes would make just the right sort of settlers for Maine. When Thomas became consul in Goteborg (Gothenburg), he made immediate plans for encouraging Swedes to emigrate to America.” E. John B. Allen, “”Skeeing” in Maine: The Early Years, 1870s to 1920s”, Maine Historical Society Quarterly , 30, 3 & 4, Winter, Spring 1991, 149. July 23, 1870 "Widgery Thomas and his group of 22 men, 11 women and 18 children arrived at a site in the woods north of Caribou. -

Geologic Site of the Month: Glacial and Postglacial

White Mountain National Forest, Western ME Maine Geological Survey Maine Geologic Facts and Localities December, 2002 Glacial and Postglacial Geology Highlights in the White Mountain National Forest, Western Maine 44° 18‘ 37.24“ N, 70° 49‘ 24.26“ W Text by Woodrow B. Thompson Maine Geological Survey Maine Geological Survey, Department of Agriculture, Conservation & Forestry 1 White Mountain National Forest, Western ME Maine Geological Survey Introduction The part of the White Mountain National Forest (WMNF) in western Maine contains scenic high mountains (including the Caribou-Speckled Wilderness), hiking trails, and campgrounds. A variety of interesting geological features can be seen along the Forest roads and trails. This field guide is intended as a resource for persons who are visiting the Forest and would like information about the glacial and postglacial geology of the region. The selection of sites included here is based on geologic mapping by the author, and more sites may be added to this website as they are discovered in the future. The WMNF in Maine is an irregular patchwork of Federal lands mingled with tracts of private property. Boundaries may change from time to time, but the Forest lands included in this field trip are shown on the Speckled Mountain and East Stoneham 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle maps. Most of the sites described here are within the Forest and open to the public. A few additional sites in the nearby Crooked River and Pleasant River valleys are also mentioned to round out the geological story. Please keep in mind that although the latter places may be visible from roads, they are private property. -

Land Areas of the National Forest System

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2012 Forest Service WO Lands FS-383 November 2012 United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS-383 System January 2013 As of September 30, 2012 Published by: USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, D.C. 20250-0003 Web site: http://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar/ Cover Photo: Mt. Edgecumbe, Kruzof Island, Alaska Courtesy of: Jeffery Wickett Table of Contents Table 1 – National and Regional Areas Summary ...............................................................1 Table 2 – Regional Areas Summary ....................................................................................2 Table 3 – Areas by Region...................................................................................................4 Table 4 – Areas by State ....................................................................................................17 Table 5 – Areas in Multiple States .....................................................................................51 Table 6 – NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County ..............................56 Table 7 – National Wilderness Areas by State ................................................................109 Table 8 – National Wilderness Areas in Multiple States .................................................127 Table 9 – National Wilderness State Acreage Summary .................................................130 -

The Ecological Values of the Western Maine Mountains

DIVERSITY, CONTINUITY AND RESILIENCE – THE ECOLOGICAL VALUES OF THE WESTERN MAINE MOUNTAINS By Janet McMahon, M.S. Occasional Paper No. 1 Maine Mountain Collaborative P.O. Box A Phillips, ME 04966 © 2016 Janet McMahon Permission to publish and distribute has been granted by the author to the Maine Mountain Collaborative. This paper is published by the Maine Mountain Collaborative as part of an ongoing series of informational papers. The information and views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Maine Mountain Collaborative or its members. Cover photo: Caribou Mountain by Paul VanDerWerf https://www.flickr.com/photos/12357841@N02/9785036371/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/ DIVERSITY, CONTINUITY AND RESILIENCE – THE ECOLOGICAL VALUES OF THE WESTERN MAINE MOUNTAINS Dawn over Crocker and Redington Mountains Photo courtesy of The Trust for Public Land, Jerry Monkman, EcoPhotography.com Abstract The five million acre Western Maine Mountains region is a landscape of superlatives. It includes all of Maine’s high peaks and contains a rich diversity of ecosystems, from alpine tundra and boreal forests to ribbed fens and floodplain hardwood forests. It is home to more than 139 rare plants and animals, including 21 globally rare species and many others that are found only in the northern Appalachians. It includes more than half of the United States’ largest globally important bird area, which provides crucial habitat for 34 northern woodland songbird species. It provides core habitat for marten, lynx, loon, moose and a host of other iconic Maine animals. Its cold headwater streams and lakes comprise the last stronghold for wild brook trout in the eastern United States. -

Discover New Places to Hike, Bike

Allagash Falls by Garrett Conover Explore MAINE 2019 WHAT’S INSIDE: Discover New Places to Hike, Bike, Swim, & More Favorite Protected Places Where in Maine do you want to go this summer? This year’s edition of Explore Maine offers spectacular places personally picked by NRCM staff, board, and members who know them well. Working together, over the last Books & Blogs 60 years, we helped ensure these places would be always be protected, for generations to come. We hope by NRCM Members you’ll make time to enjoy any and all of these recommendations. For even more ideas, visit our online Explore Maine map at www.nrcm.org. Cool Apps It is also our pleasure to introduce you to books and blogs by NRCM members. Adventure books, Explore Great Maine Beer biographies, children’s books, poetry—this year’s collection represents a wonderful diversity that you’re sure to enjoy. Hear first-hand from someone who has taken advantage of the discount many Maine sporting camps Maine Master provide to NRCM members. Check out our new map of breweries who are members of our Maine Brewshed Naturalist Program Alliance, where you can raise a glass in support of the clean water that is so important for great beer. And Finding Paradise we’ve reviewed some cool apps that can help you get out and explore Maine. Enjoy, and thank you for all you do to help keep Maine special. Lots More! —Allison Wells, Editor, Senior Director of Public Affairs and Communications Show your love for Explore Maine with NRCM a clean, beautiful Paddling, hiking, wildlife watching, cross-country skiing—we enjoy spending time in Maine’s great outdoors, and you’re invited to join us! environment Find out what’s coming up at www.nrcm.org. -

CHATHAM TRAILS ASSOCIATION 2062 Main Road, Chatham, NH 03813

AMC COLD RIVER CAMP NORTH CHATHAM, NEW HAMPSHIRE Guest Information: 2) Managers Welcome 18) Volunteer Info & Registration 4) Extension Season Crew 22) CTA & Registration 5) CRC Centennial 25) CRC Schedule 2017 6) Trip Leaders Welcome 27) CRC Wishlist 8) Helpful Hints 28) The Winter Cabin 10) Reservations 29) Fall & Spring Opportunities 12) Naturalist Info 31) Committee Contacts 18) GUEST INFO 32) CAMP MAP SUMMER 2016 ◊ Number 34 www.amccoldrivercamp.org 44 ˚ 14’ 10.1” N 71 ˚ 0’ 42.8” W WELCOME TO COLD RIVER CAMP, FROM YOUR MANAGERS AND CREW e are looking forward to our eighth season as summer managers at Cold River Camp! We’re also so grateful for the help of Liz and Jar- Wed Murphy, who will be filling in for us as managers in the middle of this season. Liz worked as an assistant manager here in years past so we know that camp will be in good hands. Richard Hall joins us this year as our assistant manager, and we know you’ll enjoying getting to know him. We are so happy that Zachary Porter will be heading up the kitchen staff again this year! Long-time staffer Fiona Graham joins him as the Assistant Cook. Zachary and Fiona will be joined by Ryan Brennan as our Prep Cook. We’ve hired a fantastic and energetic crew for this season. Our one returning crew member Sylvia Cheever brings both a savvy under- standing of the inner workings of camp as well as the perspective of a long-time camp guest. Eva Thibeault has worked as fill-in crew and has been coming to camp for years. -

Spirit Leveling in Maine

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRANKLIN K. LANE, Secretary UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, Director Bulletin 633 <- < -££>, SPIRIT LEVELING IN MAINE 1899-1915 R. B. MARSHALL, CHIEF GEOGRAPHER Work done in cooperation with the State WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1916 ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE PKOCUKED FKOM THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON, D. C. AT 5 CENTS PER COPY CONTENTS. Introduction............................................................. 5 Cooperation.......................................................... 5 Previous publication................................................. 5 Personnel............................................................. 5 Classification.......................................................... 5 Bench marks......................................................... 6 Datum............................................................... 6 Topographic maps.................................................... 7 Precise leveling.......................................................... 8 Bath, Freeport, Gray, Kezar Falls, Portland, and Sebago quadrangles (Cum berland and Oxford counties)........................................ 8 Primary leveling......................................................... 10 Portland quadrangle (Cumberland and York counties).................. 10 Anson, Augusta, Bingham, Brassua Lake, Kingsbury, Moosehead, Norridge- wock, Skowhegan, The Forks, Vassalboro, and Waterville quadrangles (Kennebec, Somerset, -

Explore Maine 2016

2016 SPECIAL EDITION EXPLORE MAINE TUMBLEDOWN MOUNTAIN BY BILL AMOS WINNER OF OUR “I LOVE OUR MAINE LANDS” PHOTO CONTEST Places to Explore, Books by NRCM Members, and Much More This year’s edition of Explore Maine is so packed with ways to enjoy our great state that we expanded it to eight pages! In honor of the 50th anniversary of the Allagash Wilderness Waterway—the issue upon which the Natural Resources Council of Maine was founded—you’ll find an in-depth article highlighting the Thard work and the individuals who made it happen, as well as NRCM’s special role in that effort. This year also marks the 100th anniversary of Acadia National Park, another of Maine’s unique gems. To keep with that theme—special places that are federally protected, owned by the people of the United States—NRCM staff, board, and fellow members share with you their experiences and tips for exploring Maine’s national wildlife refuges, wilderness areas, Acadia National Park, and the lands proposed for a new national monument. And don’t forget to download our app (see page 7). As always, you’ll also find books, blogs, sporting camps—this year, even sporting gear!—and more ways to celebrate Maine. Be sure to start your planning now, and enjoy all of what Maine’s summer has to offer.—Allison Childs Wells, Editor Are you an author? Artist? Musician? Nature-based business owner? If so, we invite you to send us information about your work so we can make it available on our website and perhaps feature it in next year’s edition of Explore Maine. -

Western Mountains Region Management Plan

Western Mountains Region Management Plan View of Mahoosuc Mountains from Table Rock Maine Department of Conservation Bureau of Parks and Lands January 4, 2011 Table of Contents Acknowledgements........................................................................................................................iii I. Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 1 About This Document..................................................................................................................... 1 What Parks and Lands are included in the Western Mountains Region?....................................... 2 II. The Planning Process and Resource Allocation System ...................................................... 5 Statutory and Policy Guidance........................................................................................................ 5 Public Participation and the Planning Process........................................................................ 5 Summary of the Resource Allocation System ................................................................................ 7 III. The Planning Context ......................................................................................................... 10 Conservation Lands and Initiatives in the Western Mountains Region........................................ 10 Recreation Resources and Initiatives in the Western Mountains Region..................................... 14 Planning