Geologic Site of the Month: Glacial and Postglacial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dry River Wilderness

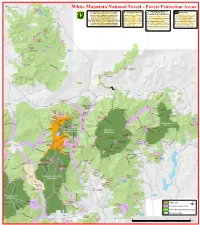

«¬110 SOUTH White Mountain National Forest - Forest Protection Areas POND !5 !B Forest Protection Areas (FPAs) are geographic South !9 Designated Sites !9 The Alpine Zone Wilderness Pond areas where certain activities are restricted to A Rarity in the Northeast Rocky prevent overuse or damage to National Forest Designated sites are campsites or Wilderness Areas are primitive areas Pond resources. Restrictions may include limits on picnic areas within a Forest The alpine zone is a high elevation area in with few signs or other developments. !B camping, use of wood or charcoal fires and Protection area where otherwise which trees are naturally absent or stunted Trails may be rough and difficult to maximum group size. FPAs surround certain features prohibited activities (camping at less that eight feet tall. About 8 square follow. Camping and fires are gererally miles of this habitat exists in the prohibited within 200 feet of any trail W (trails, ponds, parking areas, etc) with either a 200-foot and/or fires) may occur. These e s or ¼ mile buffer. They are marked with signs sites are identified by an official Northeast with most of it over 4000 feet unless at a designated site. No more t M as you enter and exit so keep your eyes peeled. sign, symbol or map. in elevation. Camping is prohibited in the than ten people may occupy a single i la TYPE Name GRID n alpine zone unless there is two or more campsite or hike in the same party. Campgrounds Basin H5 feet of snow. Fires are prohibited at all Big Rock E7 !B Blackberry Crossing G8 ROGERS times. -

Land Areas of the National Forest System

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2018 Forest Service WO Lands FS-383 November 2018 United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS-383 System November 2018 As of September 30, 2018 Published by: USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, D.C. 20250-0003 Web site: https://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar-index.shtml Cover photo courtesy of: Chris Chavez Statistics are current as of: 10/15/2018 The National Forest System (NFS) is comprised of: 154 National Forests 58 Purchase Units 20 National Grasslands 7 Land Utilization Projects 17 Research and Experimental Areas 28 Other Areas NFS lands are found in 43 States as well as Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. TOTAL NFS ACRES = 192,948,059 NFS lands are organized into: 9 Forest Service Regions 112 Administrative Forest or Forest-level units 506 Ranger District or District-level units The Forest Service administers 128 Wild and Scenic Rivers in 23 States and 446 National Wilderness Areas in 39 States. The FS also administers several other types of nationally-designated areas: 1 National Historic Area in 1 State 1 National Scenic Research Area in 1 State 1 Scenic Recreation Area in 1 State 1 Scenic Wildlife Area in 1 State 2 National Botanical Areas in 1 State 2 National Volcanic Monument Areas in 2 States 2 Recreation Management Areas in 2 States 6 National Protection Areas in 3 States 8 National Scenic Areas in 6 States 12 National Monument Areas in 6 States 12 Special Management Areas in 5 States 21 National Game Refuge or Wildlife Preserves in 12 States 22 National Recreation Areas in 20 States Table of Contents Acreage Calculation ........................................................................................................... -

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA)

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 10/01/2019 to 12/31/2019 White Mountain National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact White Mountain National Forest Androscoggin Ranger District (excluding Projects occurring in more than one District) R9 - Eastern Region Evans Brook Vegetation - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants In Progress: Expected:01/2020 06/2020 Patricia Nasta Management Project - Forest products Comment Period Public Notice 207-824-2813 EA - Vegetation management 05/15/2019 [email protected] *UPDATED* (other than forest products) Description: Proposed timber harvest using even-aged and uneven-aged management methods to improve forest health, improve wildlife habitat diversity, and provide for a sustainable yield of forest products. Connected road work will be proposed as well. Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=52040 Location: UNIT - Androscoggin Ranger District. STATE - Maine. COUNTY - Oxford. LEGAL - Not Applicable. The proposed units are located between Hastings Campground and Evans Notch along Route 113, and west of Route 113 from Bull Brook north. Peabody West Conceptual - Recreation management Developing Proposal Expected:12/2021 01/2022 Johnida Dockens Proposal Development - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants Est. Scoping Start 11/2019 207-323-5683 EA - Forest products johnida.dockens@usda. - Vegetation management gov (other than forest products) - Road management Description: The Androscoggin Ranger District of the White Mountain National Forest is in the early stages of proposal development for management activities within the conceptual Peabody West area, Coos County, NH. -

SMPDC Region

Southern Maine Regional Planning Commission Region Shelburne Batchelders Grant Twp Woodstock Sumner Hartford Mason Twp Beans Purchase Greenwood West Paris Miles Knob !! Miles Notch Number Eight Pond ! Albany Twp Shirley Brook ! Speckled Mountain ! Red Rock Brook Pine Mountain ! ! Lombard Pond ! Isaiah Mountain 3 ! 1 1 Hannah Brook E ! ! Ha T Stoneham ! y R R Sugarloaf Mountain d Willard Brook ! Goodwin Brook T Sugarloaf Mountain S ! B W Virginia Lake in Basin Brook ir Buckfield Brickett Place ! c B ! ! H h ! ro u Cecil Mountain w t A n R ! v R Bickford Brook d Co d d ld ! ! R Bro ok T rl B k Bartlett Brook o d a o R ! n r llen u C G B Beaver Brook ! d r r Mason Hill o Palmer Mountain M d o ! v f o d ! e u R k R r S n r c d i to t n a R e H A ld e R B o in u d k se Rattlesnake Mountain e d r i r Rd ! R Little Pond a f e a t d d m W e ! tl is R B l d t d s i d l n S L R A R l Rattlesnake Brook R n R il M A c ! I t ! a ! o B H in s ! d rs l e n e n r ! e l M S i a t e t d t Adams Mountain id e d u Shell Pond u l B n o l d h e Harding Hill o S o ! a y R R P G m d W d Stiles Mountain d d Great B!rook o Pine Hill R ! n n R ! R d ! y o n ! lle P Pine Hill d R a ee Cold B!rook d Pike's Peak V ll K n e c ! Foster Hill Little Deer HillDeer Hill ee h M Birch Island ! ! ! ! r S ! rg oe Mud Pond Upper Bay ve J Bradley Pond E ! Sheep Islan!d A ! ! nd Amos Mountain C Allen Mountain Paris re ! us ! n w Flat Hill h Rattlesnake Island L s m L ! Deer Hill Spring Harndon Hill Horseshoe Pond r n a Trout Pond ! ! ! e n W d P ! lm o ! Weymouth HillWeymouth -

Speckled Mountain Heritage Hikes Bickford Brook and Blueberry Ridge Trails – 8.2-Mile Loop, Strenuous

Natural Speckled Mountain Heritage Hikes Bickford Brook and Blueberry Ridge Trails – 8.2-mile loop, strenuous n the flanks and summit of Speckled Mountain, human and natural history mingle. An old farm Oroad meets a fire tower access path to lead you through a menagerie of plants, animals, and natural communities. On the way down Blueberry Ridge, 0with0.2 a sea 0.4 of blueberry 0.8 bushes 1.2 at 1.6 your feet and spectacular views around every bend, the rewards of the summit seem endless. Miles Getting There Click numbers to jump to descriptions. From US Route 2 in Gilead, travel south on Maine State Route 113 for 10 miles to the parking area at Brickett Place on the east side of the road. From US Route 302 in Fryeburg, travel north on Maine State Route 113 for 19 miles to Brickett Place. 00.2 0.4 0.8 1.2 1.6 Miles A House of Many Names -71.003608, 44.267292 Begin your hike at Brickett Place Farm. In the 1830s, a century before present-day Route 113 sliced through Evans Notch, John Brickett and Catherine (Whitaker) Brickett built this farmhouse from home- made bricks. Here, they raised nine children alongside sheep, pigs, cattle, and chick- ens. Since its acquisition by the White Mountain National Forest in 1918, Brickett Place Farmhouse has served as Civilian Conservation Corps headquarters (1930s), Cold River Ranger Station (1940s), an Appalachian Mountain Club Hut (1950s), and a Boy Scouts of America camp (1960-1993). Today, Brickett Place Farmhouse has gone through a thorough restoration and re- mains the oldest structure in the eastern region of the Forest Service. -

Amc Cold River Camp

AMC COLD RIVER CAMP NORTH CHATHAM, NEW HAMPSHIRE Winter 2018 ◊ Number 37 www.amccoldrivercamp.org 44 ˚ 14’ 10.1” N 71 ˚ 0’ 42.8” W CHAIRMAN’S WELCOME Dover, New Hampshire, January 2018 Dear Cold River Camp community, ctober 27, 2017. Needle ice. Those exquisite, fragile crystalline columns of ice that grow out of the ground when conditions are right – mois- Oture-saturated unfrozen dirt and the air temperature below freezing. Beth and I were headed up the A-Z and Mount Tom Spur trails to the Mount Tom summit. Not much of a view to be had up there, but what a special hike! A couples miles of trail whose sides were strewn with oodles of patches and swaths of needle ice. A fairyland of sorts. You just never know what treasure the next hike will reveal. July 1, 2018. That day will mark the one hundred years duration of Cold River Camp’s operation serving guests as an Appalachian Mountain Club facility. Imagine that! All the guest footsteps walking our same trails. All the conver- sations at meals. The songs, poems and skits evoked and shared on Talent Nights. And volunteer-managed all that time. It is marvelous that so many of our CRC community carry on that tradition of committed investment. But we’ll hold our enthusiasm in check and do our celebrating in our 100th anniversary year, which will be 2019. A celebration committee has been at hard at work for about two years. You can read more about that on page 18 of this LDD. -

Building a Sustainable Natural Resource-Based Economy

Blaine House Conference on Maine’s Natural Resource-based Industry: Charting a New Course November 17, 2003 onference Report With recommendations to Governor John E. Baldacci Submitted by the Conference Planning Committee Richard Barringer and Richard Davies, Co-chairs February 2004 . Acknowledgements The following organizations made the conference possible with their generous contributions: Conference Sponsors The Betterment Fund Finance Authority of Maine LL Bean, Inc. Maine Community Foundation US Fish and Wildlife Service US Forest Service This report was compiled and edited by: Maine State Planning Office 38 State House Station Augusta, ME 04333 (207) 287-3261 www.maine/gov/spo February 2004 Printed under Appropriation #014 07B 3340 2 . Conference Planning Committee Richard Barringer, Co-chair, Richard Davies, Co-chair Professor, Muskie School of Public Service, Senior Policy Advisor, Governor Office USM Dann Lewis Spencer Apollonio Director, Office of Tourism, DECD Former Commissioner, Dept of Marine Resources Roland D. Martin Commissioner, Dept of Inland Fisheries and Edward Bradley Wildlife Maritime Attorney Patrick McGowan Elizabeth Butler Commissioner, Dept of Conservation Pierce Atwood Don Perkins Jack Cashman President, Gulf of Maine Research Institute Commissioner, Dept of Economic and Community Development Stewart Smith Professor, Sustainable Agriculture Policy, Charlie Colgan UMO Professor, Muskie School of Public Service, USM Robert Spear Commissioner, Dept of Agriculture Martha Freeman Director, State Planning Office -

Open Space Policy 8 04 09

Western Maine Regional Open Space Bethel Area Chamber of Commerce Policy Bruce Clendenning May 2009 1 Table of Contents Section 1: Background For Policy Development Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................. 1 Regional Background .............................................................................................................................................. 4 The Regional Policy Framework ........................................................................................................................... 12 Regional Policy Development ............................................................................................................................... 14 Section 2: Policy Overarching Policy and Priorities .......................................................................................................................... 17 Special Considerations for Municipal Planning .................................................................................................... 18 Landscape Conservation Including Large Blocks and Remote Areas .................................................................. 19 National Areas, Endangered and Threatened Species, and Critical Habitats and Other Land Supporting Vital Ecological Values or Functions ................................................................................ 21 Riparian Areas and Wildlife Corridors; Riparian Areas for Active -

Timeline of Maine Skiing New England Ski Museum in Preparation for 2015 Annual Exhibit

Timeline of Maine Skiing New England Ski Museum In preparation for 2015 Annual Exhibit Mid 1800s: “…the Maine legislature sought to populate the vast forests of northern Maine. It offered free land to anyone who would take up the challenge of homesteading in this wilderness. ...Widgery Thomas, state legislator and ex-Ambassador to Sweden…suggested that the offer of free land be made to people in Sweden. In May, 1870 Thomas sailed for Sweden to offer 100 acres of land to any Swede willing to settle in Maine. Certificates of character were required. Thomas himself had to approve each recruit.” Glenn Parkinson, First Tracks: Stories from Maine’s Skiing Heritage . (Portland: Ski Maine, 1995), 4. March 1869: “In March 1869 the state resolved “to promote the settlement of the public and other lands” by appointing three commissioners of settlement. William Widgery Thomas, Jr., one of the commissioners, had extensive diplomatic experience as ambassador to Sweden for Presidents Arthur and Harrison. Thomas had lived among the Swedes for years and was impressed with their hardy quality. He returned to the United States convinced that Swedes would make just the right sort of settlers for Maine. When Thomas became consul in Goteborg (Gothenburg), he made immediate plans for encouraging Swedes to emigrate to America.” E. John B. Allen, “”Skeeing” in Maine: The Early Years, 1870s to 1920s”, Maine Historical Society Quarterly , 30, 3 & 4, Winter, Spring 1991, 149. July 23, 1870 "Widgery Thomas and his group of 22 men, 11 women and 18 children arrived at a site in the woods north of Caribou. -

Camp Pondicherry Weekend Excursions (Updated Summer 2018)

Camp Pondicherry Weekend Excursions (updated Summer 2018) Hiking, Walking Trails & Scenic Sites Pleasant Mountain, Denmark, ME Pleasant Mountain is the tallest mountain in southern Maine, reaching over 2,000 feet. With a 10.5 mile network of trails, the mountain offers a wide range of trail options. Home of Shawnee Peak ski area. https://www.mainetrailfinder.com/trails/trail/pleasant-mountain-trails Holt Pond Preserve, Bridgton, ME Less than 3 miles away, this preserve was created to educate people on wetlands. It encompasses 400 acres, and is home to a variety of wildlife, such as sub-tropical birds, beavers, moose, and various fish. The trail travels through mixed forests and swampland, as well as rivers and bog areas. The trail consists of easy terrain across the forest floor, and established boardwalks. http://www.mainelakes.org/trailspreserves/holt-pond-preserve/ Hawk Mountain, Waterford, ME A moderate-grade 0.7 mile trail which leads to an open summit. The summit features broad cliffs and a panoramic view – great for picnics and birdwatching – containing Pleasant Mountain. https://www.mainetrailfinder.com/trails/trail/hawk-mountain Blueberry Mountain, Stoneham, ME Within Evans Notch in the White Mountain National Forest is Blueberry Mountain, with a short 3.9 mile trail even small children can enjoy. If you get hot along the way, there is a small side trail along the Blueberry Mountain path that leads to Rattlesnake Pond, great for a cooling dip. https://www.outdoors.org/articles/amc-outdoors/hiking-blueberry-mountain-and Pondicherry Park, Bridgton, ME Just 5 miles from Camp Pondicherry, the park features 66 acres of woodlands and streams in the heart of Bridgton. -

The Regions of Maine MAINE the Maine Beaches Long Sand Beaches and the Most Forested State in America Amusements

the Regions of Maine MAINE The Maine Beaches Long sand beaches and The most forested state in America amusements. Notable birds: Piping Plover, Least Tern, also has one of the longest Harlequin Duck, and Upland coastlines and hundreds of Sandpiper. Aroostook County lakes and mountains. Greater Portland The birds like the variety. and Casco Bay Home of Maine’s largest city So will you. and Scarborough Marsh. Notable birds: Roseate Tern and Sharp-tailed Sparrow. Midcoast Region Extraordinary state parks, islands, and sailing. Notable birds: Atlantic Puffin and Roseate Tern. Downeast and Acadia Land of Acadia National Park, national wildlife refuges and state parks. Notable birds: Atlantic Puffin, Razorbill, and The Maine Highlands Spruce Grouse. Maine Lakes and Mountains Ski country, waterfalls, scenic nature and solitude. Notable birds: Common Loon, Kennebec & Philadelphia Vireo, and Moose River Downeast Boreal Chickadee. Valleys and Acadia Maine Lakes Kennebec & and Mountains Moose River Valleys Great hiking, white-water rafting and the Old Canada Road scenic byway. Notable birds: Warbler, Gray Jay, Crossbill, and Bicknell’s Thrush. The Maine Highlands Site of Moosehead Lake and Midcoast Mt. Katahdin in Baxter State Region Park. Notable birds: Spruce Grouse, and Black-backed Woodpecker. Greater Portland and Casco Bay w. e. Aroostook County Rich Acadian culture, expansive agriculture and A rich landscape and s. rivers. Notable birds: Three- cultural heritage forged The Maine Beaches toed Woodpecker, Pine by the forces of nature. Grossbeak, and Crossbill. 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 Scale of Miles Contents maine Woodpecker, Yellow-bellied Flycatcher, Philadelphia Vireo, Gray Jay, Boreal Chickadee, Bicknell’s Thrush, and a variety of warblers. -

Land Areas of the National Forest System

United States Department of Agriculture Land Areas of the National Forest System As of September 30, 2012 Forest Service WO Lands FS-383 November 2012 United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Land Areas of the WO, Lands National Forest FS-383 System January 2013 As of September 30, 2012 Published by: USDA Forest Service 1400 Independence Ave., SW Washington, D.C. 20250-0003 Web site: http://www.fs.fed.us/land/staff/lar/ Cover Photo: Mt. Edgecumbe, Kruzof Island, Alaska Courtesy of: Jeffery Wickett Table of Contents Table 1 – National and Regional Areas Summary ...............................................................1 Table 2 – Regional Areas Summary ....................................................................................2 Table 3 – Areas by Region...................................................................................................4 Table 4 – Areas by State ....................................................................................................17 Table 5 – Areas in Multiple States .....................................................................................51 Table 6 – NFS Acreage by State, Congressional District and County ..............................56 Table 7 – National Wilderness Areas by State ................................................................109 Table 8 – National Wilderness Areas in Multiple States .................................................127 Table 9 – National Wilderness State Acreage Summary .................................................130