Open Space Policy 8 04 09

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dry River Wilderness

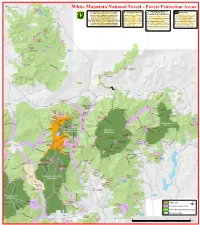

«¬110 SOUTH White Mountain National Forest - Forest Protection Areas POND !5 !B Forest Protection Areas (FPAs) are geographic South !9 Designated Sites !9 The Alpine Zone Wilderness Pond areas where certain activities are restricted to A Rarity in the Northeast Rocky prevent overuse or damage to National Forest Designated sites are campsites or Wilderness Areas are primitive areas Pond resources. Restrictions may include limits on picnic areas within a Forest The alpine zone is a high elevation area in with few signs or other developments. !B camping, use of wood or charcoal fires and Protection area where otherwise which trees are naturally absent or stunted Trails may be rough and difficult to maximum group size. FPAs surround certain features prohibited activities (camping at less that eight feet tall. About 8 square follow. Camping and fires are gererally miles of this habitat exists in the prohibited within 200 feet of any trail W (trails, ponds, parking areas, etc) with either a 200-foot and/or fires) may occur. These e s or ¼ mile buffer. They are marked with signs sites are identified by an official Northeast with most of it over 4000 feet unless at a designated site. No more t M as you enter and exit so keep your eyes peeled. sign, symbol or map. in elevation. Camping is prohibited in the than ten people may occupy a single i la TYPE Name GRID n alpine zone unless there is two or more campsite or hike in the same party. Campgrounds Basin H5 feet of snow. Fires are prohibited at all Big Rock E7 !B Blackberry Crossing G8 ROGERS times. -

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA)

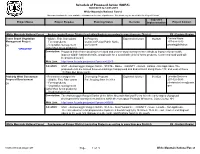

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 10/01/2019 to 12/31/2019 White Mountain National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact White Mountain National Forest Androscoggin Ranger District (excluding Projects occurring in more than one District) R9 - Eastern Region Evans Brook Vegetation - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants In Progress: Expected:01/2020 06/2020 Patricia Nasta Management Project - Forest products Comment Period Public Notice 207-824-2813 EA - Vegetation management 05/15/2019 [email protected] *UPDATED* (other than forest products) Description: Proposed timber harvest using even-aged and uneven-aged management methods to improve forest health, improve wildlife habitat diversity, and provide for a sustainable yield of forest products. Connected road work will be proposed as well. Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=52040 Location: UNIT - Androscoggin Ranger District. STATE - Maine. COUNTY - Oxford. LEGAL - Not Applicable. The proposed units are located between Hastings Campground and Evans Notch along Route 113, and west of Route 113 from Bull Brook north. Peabody West Conceptual - Recreation management Developing Proposal Expected:12/2021 01/2022 Johnida Dockens Proposal Development - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants Est. Scoping Start 11/2019 207-323-5683 EA - Forest products johnida.dockens@usda. - Vegetation management gov (other than forest products) - Road management Description: The Androscoggin Ranger District of the White Mountain National Forest is in the early stages of proposal development for management activities within the conceptual Peabody West area, Coos County, NH. -

Speckled Mountain Heritage Hikes Bickford Brook and Blueberry Ridge Trails – 8.2-Mile Loop, Strenuous

Natural Speckled Mountain Heritage Hikes Bickford Brook and Blueberry Ridge Trails – 8.2-mile loop, strenuous n the flanks and summit of Speckled Mountain, human and natural history mingle. An old farm Oroad meets a fire tower access path to lead you through a menagerie of plants, animals, and natural communities. On the way down Blueberry Ridge, 0with0.2 a sea 0.4 of blueberry 0.8 bushes 1.2 at 1.6 your feet and spectacular views around every bend, the rewards of the summit seem endless. Miles Getting There Click numbers to jump to descriptions. From US Route 2 in Gilead, travel south on Maine State Route 113 for 10 miles to the parking area at Brickett Place on the east side of the road. From US Route 302 in Fryeburg, travel north on Maine State Route 113 for 19 miles to Brickett Place. 00.2 0.4 0.8 1.2 1.6 Miles A House of Many Names -71.003608, 44.267292 Begin your hike at Brickett Place Farm. In the 1830s, a century before present-day Route 113 sliced through Evans Notch, John Brickett and Catherine (Whitaker) Brickett built this farmhouse from home- made bricks. Here, they raised nine children alongside sheep, pigs, cattle, and chick- ens. Since its acquisition by the White Mountain National Forest in 1918, Brickett Place Farmhouse has served as Civilian Conservation Corps headquarters (1930s), Cold River Ranger Station (1940s), an Appalachian Mountain Club Hut (1950s), and a Boy Scouts of America camp (1960-1993). Today, Brickett Place Farmhouse has gone through a thorough restoration and re- mains the oldest structure in the eastern region of the Forest Service. -

Amc Cold River Camp

AMC COLD RIVER CAMP NORTH CHATHAM, NEW HAMPSHIRE Winter 2018 ◊ Number 37 www.amccoldrivercamp.org 44 ˚ 14’ 10.1” N 71 ˚ 0’ 42.8” W CHAIRMAN’S WELCOME Dover, New Hampshire, January 2018 Dear Cold River Camp community, ctober 27, 2017. Needle ice. Those exquisite, fragile crystalline columns of ice that grow out of the ground when conditions are right – mois- Oture-saturated unfrozen dirt and the air temperature below freezing. Beth and I were headed up the A-Z and Mount Tom Spur trails to the Mount Tom summit. Not much of a view to be had up there, but what a special hike! A couples miles of trail whose sides were strewn with oodles of patches and swaths of needle ice. A fairyland of sorts. You just never know what treasure the next hike will reveal. July 1, 2018. That day will mark the one hundred years duration of Cold River Camp’s operation serving guests as an Appalachian Mountain Club facility. Imagine that! All the guest footsteps walking our same trails. All the conver- sations at meals. The songs, poems and skits evoked and shared on Talent Nights. And volunteer-managed all that time. It is marvelous that so many of our CRC community carry on that tradition of committed investment. But we’ll hold our enthusiasm in check and do our celebrating in our 100th anniversary year, which will be 2019. A celebration committee has been at hard at work for about two years. You can read more about that on page 18 of this LDD. -

Building a Sustainable Natural Resource-Based Economy

Blaine House Conference on Maine’s Natural Resource-based Industry: Charting a New Course November 17, 2003 onference Report With recommendations to Governor John E. Baldacci Submitted by the Conference Planning Committee Richard Barringer and Richard Davies, Co-chairs February 2004 . Acknowledgements The following organizations made the conference possible with their generous contributions: Conference Sponsors The Betterment Fund Finance Authority of Maine LL Bean, Inc. Maine Community Foundation US Fish and Wildlife Service US Forest Service This report was compiled and edited by: Maine State Planning Office 38 State House Station Augusta, ME 04333 (207) 287-3261 www.maine/gov/spo February 2004 Printed under Appropriation #014 07B 3340 2 . Conference Planning Committee Richard Barringer, Co-chair, Richard Davies, Co-chair Professor, Muskie School of Public Service, Senior Policy Advisor, Governor Office USM Dann Lewis Spencer Apollonio Director, Office of Tourism, DECD Former Commissioner, Dept of Marine Resources Roland D. Martin Commissioner, Dept of Inland Fisheries and Edward Bradley Wildlife Maritime Attorney Patrick McGowan Elizabeth Butler Commissioner, Dept of Conservation Pierce Atwood Don Perkins Jack Cashman President, Gulf of Maine Research Institute Commissioner, Dept of Economic and Community Development Stewart Smith Professor, Sustainable Agriculture Policy, Charlie Colgan UMO Professor, Muskie School of Public Service, USM Robert Spear Commissioner, Dept of Agriculture Martha Freeman Director, State Planning Office -

Geologic Site of the Month: Glacial and Postglacial

White Mountain National Forest, Western ME Maine Geological Survey Maine Geologic Facts and Localities December, 2002 Glacial and Postglacial Geology Highlights in the White Mountain National Forest, Western Maine 44° 18‘ 37.24“ N, 70° 49‘ 24.26“ W Text by Woodrow B. Thompson Maine Geological Survey Maine Geological Survey, Department of Agriculture, Conservation & Forestry 1 White Mountain National Forest, Western ME Maine Geological Survey Introduction The part of the White Mountain National Forest (WMNF) in western Maine contains scenic high mountains (including the Caribou-Speckled Wilderness), hiking trails, and campgrounds. A variety of interesting geological features can be seen along the Forest roads and trails. This field guide is intended as a resource for persons who are visiting the Forest and would like information about the glacial and postglacial geology of the region. The selection of sites included here is based on geologic mapping by the author, and more sites may be added to this website as they are discovered in the future. The WMNF in Maine is an irregular patchwork of Federal lands mingled with tracts of private property. Boundaries may change from time to time, but the Forest lands included in this field trip are shown on the Speckled Mountain and East Stoneham 1:24,000 topographic quadrangle maps. Most of the sites described here are within the Forest and open to the public. A few additional sites in the nearby Crooked River and Pleasant River valleys are also mentioned to round out the geological story. Please keep in mind that although the latter places may be visible from roads, they are private property. -

Camp Pondicherry Weekend Excursions (Updated Summer 2018)

Camp Pondicherry Weekend Excursions (updated Summer 2018) Hiking, Walking Trails & Scenic Sites Pleasant Mountain, Denmark, ME Pleasant Mountain is the tallest mountain in southern Maine, reaching over 2,000 feet. With a 10.5 mile network of trails, the mountain offers a wide range of trail options. Home of Shawnee Peak ski area. https://www.mainetrailfinder.com/trails/trail/pleasant-mountain-trails Holt Pond Preserve, Bridgton, ME Less than 3 miles away, this preserve was created to educate people on wetlands. It encompasses 400 acres, and is home to a variety of wildlife, such as sub-tropical birds, beavers, moose, and various fish. The trail travels through mixed forests and swampland, as well as rivers and bog areas. The trail consists of easy terrain across the forest floor, and established boardwalks. http://www.mainelakes.org/trailspreserves/holt-pond-preserve/ Hawk Mountain, Waterford, ME A moderate-grade 0.7 mile trail which leads to an open summit. The summit features broad cliffs and a panoramic view – great for picnics and birdwatching – containing Pleasant Mountain. https://www.mainetrailfinder.com/trails/trail/hawk-mountain Blueberry Mountain, Stoneham, ME Within Evans Notch in the White Mountain National Forest is Blueberry Mountain, with a short 3.9 mile trail even small children can enjoy. If you get hot along the way, there is a small side trail along the Blueberry Mountain path that leads to Rattlesnake Pond, great for a cooling dip. https://www.outdoors.org/articles/amc-outdoors/hiking-blueberry-mountain-and Pondicherry Park, Bridgton, ME Just 5 miles from Camp Pondicherry, the park features 66 acres of woodlands and streams in the heart of Bridgton. -

The Regions of Maine MAINE the Maine Beaches Long Sand Beaches and the Most Forested State in America Amusements

the Regions of Maine MAINE The Maine Beaches Long sand beaches and The most forested state in America amusements. Notable birds: Piping Plover, Least Tern, also has one of the longest Harlequin Duck, and Upland coastlines and hundreds of Sandpiper. Aroostook County lakes and mountains. Greater Portland The birds like the variety. and Casco Bay Home of Maine’s largest city So will you. and Scarborough Marsh. Notable birds: Roseate Tern and Sharp-tailed Sparrow. Midcoast Region Extraordinary state parks, islands, and sailing. Notable birds: Atlantic Puffin and Roseate Tern. Downeast and Acadia Land of Acadia National Park, national wildlife refuges and state parks. Notable birds: Atlantic Puffin, Razorbill, and The Maine Highlands Spruce Grouse. Maine Lakes and Mountains Ski country, waterfalls, scenic nature and solitude. Notable birds: Common Loon, Kennebec & Philadelphia Vireo, and Moose River Downeast Boreal Chickadee. Valleys and Acadia Maine Lakes Kennebec & and Mountains Moose River Valleys Great hiking, white-water rafting and the Old Canada Road scenic byway. Notable birds: Warbler, Gray Jay, Crossbill, and Bicknell’s Thrush. The Maine Highlands Site of Moosehead Lake and Midcoast Mt. Katahdin in Baxter State Region Park. Notable birds: Spruce Grouse, and Black-backed Woodpecker. Greater Portland and Casco Bay w. e. Aroostook County Rich Acadian culture, expansive agriculture and A rich landscape and s. rivers. Notable birds: Three- cultural heritage forged The Maine Beaches toed Woodpecker, Pine by the forces of nature. Grossbeak, and Crossbill. 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 Scale of Miles Contents maine Woodpecker, Yellow-bellied Flycatcher, Philadelphia Vireo, Gray Jay, Boreal Chickadee, Bicknell’s Thrush, and a variety of warblers. -

CHATHAM TRAILS ASSOCIATION 2062 Main Road, Chatham, NH 03813

AMC COLD RIVER CAMP NORTH CHATHAM, NEW HAMPSHIRE Guest Information: 2) Managers Welcome 18) Volunteer Info & Registration 4) Extension Season Crew 22) CTA & Registration 5) CRC Centennial 25) CRC Schedule 2017 6) Trip Leaders Welcome 27) CRC Wishlist 8) Helpful Hints 28) The Winter Cabin 10) Reservations 29) Fall & Spring Opportunities 12) Naturalist Info 31) Committee Contacts 18) GUEST INFO 32) CAMP MAP SUMMER 2016 ◊ Number 34 www.amccoldrivercamp.org 44 ˚ 14’ 10.1” N 71 ˚ 0’ 42.8” W WELCOME TO COLD RIVER CAMP, FROM YOUR MANAGERS AND CREW e are looking forward to our eighth season as summer managers at Cold River Camp! We’re also so grateful for the help of Liz and Jar- Wed Murphy, who will be filling in for us as managers in the middle of this season. Liz worked as an assistant manager here in years past so we know that camp will be in good hands. Richard Hall joins us this year as our assistant manager, and we know you’ll enjoying getting to know him. We are so happy that Zachary Porter will be heading up the kitchen staff again this year! Long-time staffer Fiona Graham joins him as the Assistant Cook. Zachary and Fiona will be joined by Ryan Brennan as our Prep Cook. We’ve hired a fantastic and energetic crew for this season. Our one returning crew member Sylvia Cheever brings both a savvy under- standing of the inner workings of camp as well as the perspective of a long-time camp guest. Eva Thibeault has worked as fill-in crew and has been coming to camp for years. -

Oxford County Historic Skiing Sites: Interpretive Map Being Developed by Ski Museum

Celebrating and Preserving the History and Heritage of Maine Skiing • Spring 2015 SKI MUSEUM OF MAINE Oxford County Historic Skiing Sites: Interpretive map being developed by Ski Museum By Scott Andrews Editor, Snow Trail Oxford County has been a hotbed of Maine skiing for more than a century, a geographic theme that’s visually underscored by a new interpretive map that’s being developed by the Ski Museum of Maine. Oxford County’s claim to historical fame dates from the 1890s, when Finnish immigrants first settled in West Paris and surrounding towns. Skiing was one of the Finns’ many contributions to Maine’s culture. In 1895 a lone “skee-man” vistied Fryeburg. He was with a group of snowshoe enthusiasts from the Boston-based Appalachian Mountain Club. About the turn of the 20th century, the Paris Manufacturing Company began making skis. Most of the workers in the ski department were local Finns. Rumford’s long and distinguished ski history began about the time of World War I, when a Norwegian immigrant named Mat Liz Chenard and Leslie Miller were two of 37 junior athletes from Nilsen arrived in town and began to amaze Rumford’s Chisholm Ski Club who competed at the national level during local folks with his prowess on skis. A few years the 1970s. The Chisholm Ski Club, founded in 1924, is Maine’s oldest, and it boasts a long and proud history that continues to the present. later, he co-founded the Chisholm Ski Club, (Courtesy Wendall “Chummy” Broomhall) which remains active to the present. Please turn to page1 7 Upcoming Ski Museum Events Monday, June 8 Third Annual Ski Maine Golf Classic Ski Museum of Maine (to benefit Ski Museum of Maine) Snow Trail Nonesuch River Golf Course Scott Andrews, Editor Scarborough Spring 2015 www.skimuseumofmaine.org Friday, June 26 [email protected] Kingfield Pops Weekend P.O. -

Town of Fryeburg Maine Comprehensive Plan Fryeburg, Me

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Maine Town Documents Maine Government Documents 2014 Town of Fryeburg Maine Comprehensive Plan Fryeburg, Me. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/towndocs Repository Citation Fryeburg, Me., "Town of Fryeburg Maine Comprehensive Plan" (2014). Maine Town Documents. 6955. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/towndocs/6955 This Plan is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Maine Town Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Fryeburg Comprehensive Plan 2014 The Future is Now! Adopted November 3, 2015 Fryeburg Comprehensive Plan The Future is Now! Table of Contents FRYEBURG COMPREHENSIVE PLAN 2014 BACKGROUND DOCUMENT CHAPTER 1. Introduction 2. Historic and Geographic Setting 3. Natural Resources 4. Population 5. Land Use and Housing 6. Local Economy and Labor Force 7. Recreation and Cultural Resources 8. Roads, Traffic and Transportation 9. Public Facilities MAPS > Road Network > Cultural Assets > Parks > Conserved Lands and Priority Areas > Flood Zones > Beginning with Habitat - Regional Map > Beginning with Habitat - Water Resources & Riparian Habitats > Beginning with Habitat - High Value Plant & Animal Habitats > Beginning with Habitat - Undeveloped Habitat Blocks > Beginning with Habitat - Wetlands Characterization > Beginning with Habitat - USFWS Priority Trust Species Habitats > Current Zoning > Current Land Use FRYEBURG COMPREHENSIVE PLAN 2014 GOALS, POLICIES AND STRATEGIES & FUTURE LAND USE Page 1 Introduction Page 2 Goals, Policies, & Strategies Page 14 Future Land Use Fryeburg Comprehensive Plan 2014 Background Document The Future is Now! CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION The Future is Now! What is the Comprehensive Plan? This plan will update the Comprehensive Plan adopted in 1994. -

Deglaciation of the Upper Androscoggin River Valley and Northeastern White Mountains, Maine and New Hampshire

Maine Geological Survey Studies in Maine Geology: Volume 6 1989 Deglaciation of the Upper Androscoggin River Valley and Northeastern White Mountains, Maine and New Hampshire Woodrow B. Thompson Maine Geological Survey State House Station 22 Augusta, Maine 04333 Brian K. Fowler Dunn Geoscience Corporation P.O. Box 7078, Village West Laconia, New Hampshire 03246 ABSTRACT The mode of deglaciation of the White Mountains of northern New Hampshire and adjacent Maine has been a controversial topic since the late 1800's. Recent workers have generally favored regional stagnation and down wastage as the principal means by which the late Wisconsinan ice sheet disappeared from this area. However, the results of the present investigation show that active ice persisted in the upper Androscoggin River valley during late-glacial time. An ice stream flowed eastward along the narrow part of the Androscoggin Valley between the Carter and Mahoosuc Ranges, and deposited a cluster of end-moraine ridges in the vicinity of the Maine-New Hampshire border. We have named these deposits the" Androscoggin Moraine." This moraine system includes several ridges originally described by G. H. Stone in 1880, as well as other moraine segments discovered during our field work. The ridges are bouldery, sharp-crested, and up to 30 m high. They are composed of glacial diamictons, including flowtills, with interbedded silt, sand, and gravel. Stone counts show that most of the rock debris comprising the Androscoggin Moraine was derived locally, although differences in provenance may exist between moraine segments on opposite sides of the valley. Meltwater channels and deposits of ice-contact stratified drift indicate that the margin of the last ice sheet receded northwestward.