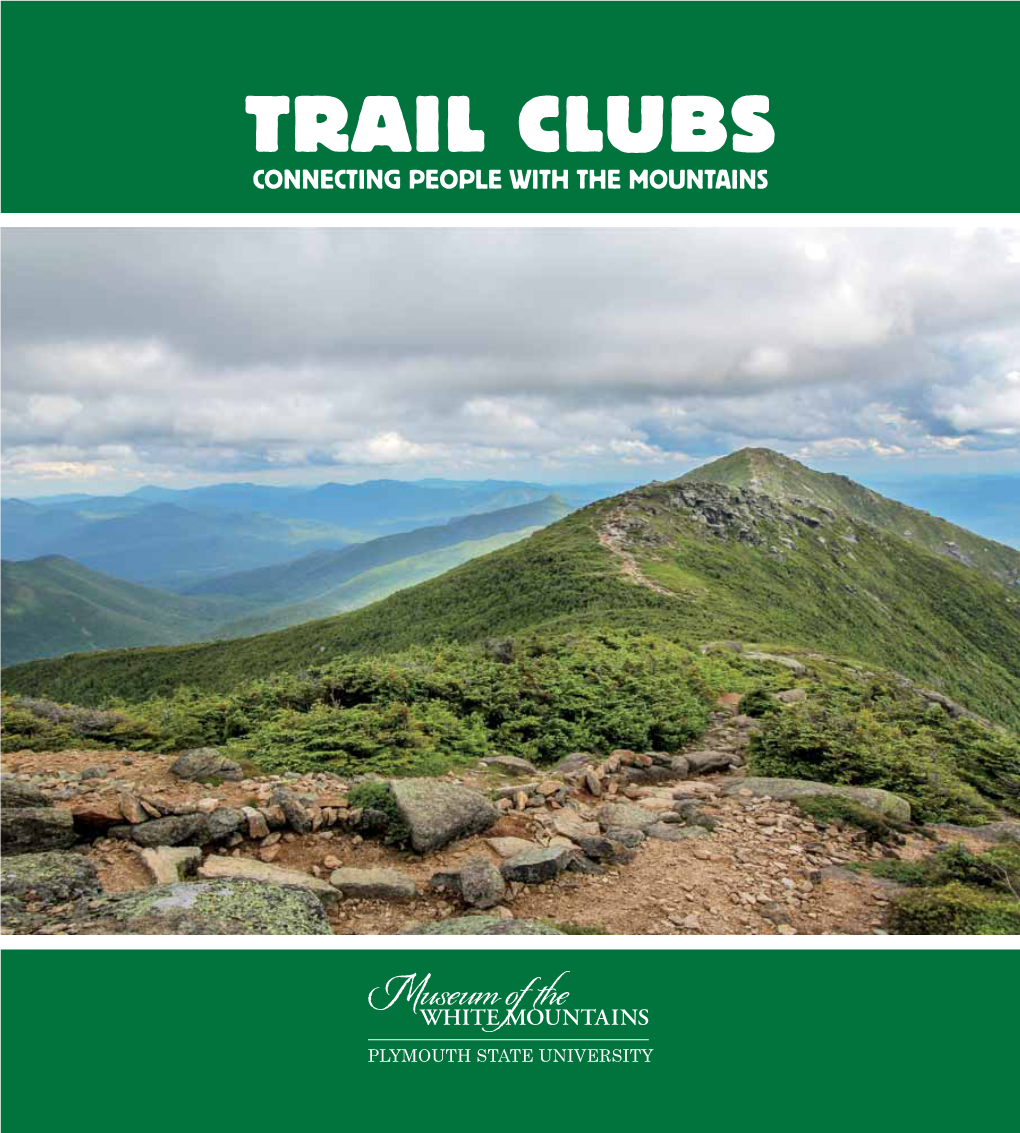

Trail Clubs Connecting People with the Mountains

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Breeze

View from the Chair by Anne Chace That Time of Year It may not have been a typical winter, but now it's time to dust off the hiking boots and get the dayhack packs ready to go. Check those bike tires and put the canoe/kayak rack on the car. And don't forget about all the trailwork that needs to be done ... it's that time of year. During this, our chapte/s Silver Jubilee year, make it a point to GET great paftici- OUTDOORSI Find an activity or two that interest you and call one of Our hosting of the AMC Spnng Gahering was a success . wheher pants wete nnping or iltnl<ed down in heabd cr,bins. Clubynile meetings were our leaders. Activity chairs and leaders have been busy during the hed, varbus chapter-bd aclivities run ..,, aN the rains held off untiltlrc very end. 'off season' preparing trips to meet varied interests. Supprt them by going on the tdps. Just pick up the phone and call or click on your s Our "Cape Cod Caper" is a big success mail. Answer the soeening questions and take the plunge. Even if Dexler Robinson, Spring Gathering Coordinator you've never participated in a chapter activi$, make a special efiort to get out on one this season, for the true spirit of the AMC is our chap On the weekend of April 26-28, our chapter hosted Spring Gathering ter activities, and SEM/AMC has some ol the best offerings. And 2002 for approximately 195 people at Camp Burgess in Sandwich. -

Spring 2012 Resuscitator — the Camp, Joan Bishop Was a Counselor, and Brooks Van Mudgekeewis Camp for Girls Everen Was a Cook

T H E O H A S S O C I A T I O N 17 Brenner Drive, Newton, New Hampshire 03858 The O H Association is former employees of the AMC Huts System whose activities include sharing sweet White Mountain memories Save the Dates 2012 Details to email later and on website May 19, Cabin Spring Reunion Prepay seafood $30, $15 current croo and kids under 14. Non-seafood is $12, $10 for croo & kids. 12:00 lunch; 4:00 lobster dinner. Walk ins-no lobster. Email Moose Meserve at [email protected] and mail check to 17 Brenner Drive, Newton, NH 03858 Gala, May 22-24 Hut croo training session GreenWool Blanket Vinnie Night, August 18 End of season croo party, Latchstring Award by Caroline Collins I October 10-12, I keep a green wool blanket in the back of my car. It’s Cabin Oktoberfest faded and tattered, but the white AMC logo is still visible. Traditional work for Bavarian victuals feast I tied it to my packboard the last time I hiked out of Carter Email Moose Meserve at [email protected] Notch Hut in the early ’90s. This summer I visited the AMC that you are coming to plan the provisions huts in the White Mountains of New Hampshire after a 22 year absence. My first experience with the Appalachian November 3, Fallfest Mountain Club was whitewater canoeing lessons in Pennsyl- Annual Meeting at vania when I was in high school. My mother was struck with Highland Center inspiration and the next thing I knew we were packing up Details to come camping equipment, canoes and kayaks, and exploring the Potomac, the Shenandoah, the Lehigh, and the Nescopeck rivers among others. -

Dry River Wilderness

«¬110 SOUTH White Mountain National Forest - Forest Protection Areas POND !5 !B Forest Protection Areas (FPAs) are geographic South !9 Designated Sites !9 The Alpine Zone Wilderness Pond areas where certain activities are restricted to A Rarity in the Northeast Rocky prevent overuse or damage to National Forest Designated sites are campsites or Wilderness Areas are primitive areas Pond resources. Restrictions may include limits on picnic areas within a Forest The alpine zone is a high elevation area in with few signs or other developments. !B camping, use of wood or charcoal fires and Protection area where otherwise which trees are naturally absent or stunted Trails may be rough and difficult to maximum group size. FPAs surround certain features prohibited activities (camping at less that eight feet tall. About 8 square follow. Camping and fires are gererally miles of this habitat exists in the prohibited within 200 feet of any trail W (trails, ponds, parking areas, etc) with either a 200-foot and/or fires) may occur. These e s or ¼ mile buffer. They are marked with signs sites are identified by an official Northeast with most of it over 4000 feet unless at a designated site. No more t M as you enter and exit so keep your eyes peeled. sign, symbol or map. in elevation. Camping is prohibited in the than ten people may occupy a single i la TYPE Name GRID n alpine zone unless there is two or more campsite or hike in the same party. Campgrounds Basin H5 feet of snow. Fires are prohibited at all Big Rock E7 !B Blackberry Crossing G8 ROGERS times. -

Summer 2004 Vol. 23 No. 2

Vol 23 No 2 Summer 04 v4 4/16/05 1:05 PM Page i New Hampshire Bird Records Summer 2004 Vol. 23, No. 2 Vol 23 No 2 Summer 04 v4 4/16/05 1:05 PM Page ii New Hampshire Bird Records Volume 23, Number 2 Summer 2004 Managing Editor: Rebecca Suomala 603-224-9909 X309 [email protected] Text Editor: Dorothy Fitch Season Editors: Pamela Hunt, Spring; William Taffe, Summer; Stephen Mirick, Fall; David Deifik, Winter Layout: Kathy McBride Production Assistants: Kathie Palfy, Diane Parsons Assistants: Marie Anne, Jeannine Ayer, Julie Chapin, Margot Johnson, Janet Lathrop, Susan MacLeod, Dot Soule, Jean Tasker, Tony Vazzano, Robert Vernon Volunteer Opportunities and Birding Research: Susan Story Galt Photo Quiz: David Donsker Where to Bird Feature Coordinator: William Taffe Maps: William Taffe Cover Photo: Juvenile Northern Saw-whet Owl, by Paul Knight, June, 2004, Francestown, NH. Paul watched as it flew up with a mole in its talons. New Hampshire Bird Records (NHBR) is published quarterly by New Hampshire Audubon (NHA). Bird sightings are submitted to NHA and are edited for publication. A computerized print- out of all sightings in a season is available for a fee. To order a printout, purchase back issues, or volunteer your observations for NHBR, please contact the Managing Editor at 224-9909. Published by New Hampshire Audubon New Hampshire Bird Records © NHA April, 2005 Printed on Recycled Paper Vol 23 No 2 Summer 04 v4 4/16/05 1:05 PM Page 1 Table of Contents In This Issue Volunteer Request . .2 A Checklist of the Birds of New Hampshire—Revised! . -

August 01, 2013

VOLUME 38, NUMBER 9 AUGUST 1, 2013 FREE THE WEEKLY NEWS & LIFESTYLE JOURNAL OF MT. WASHINGTON VALLEY Guiided Tours Daiilly or Driive Your Own Car Biking Kayaking Hiking Outfitters Shop Glen View Café Kids on Bikes Nooks & Crannies Racing Family Style Great views in the Page 23 Zealand Valley Page 22 Rt. 16, Pinkham Notch www.mtwashingtonautoroad.com A SALMON PRESS PUBLICATION • (603) 447-6336 • PUBLISHED IN CONWAY, NH (603) 466-3988 News/Round-Ups Arts Jubilee continues its 31st summer concert season NORTH CONWAY playing around having a good be hosted by the valley’s own — Arts Jubilee begins the time into a band that has theatrical celebrity, George month of August with the first gained notoriety as one of the Cleveland and will open with of two remaining concerts in Valley’s well known groups. the vocal/instrumental duo, the 31st summer concert sea- Starting off in the après mu- Dennis & Davey - whose mu- son, presenting high energy, sic scene, Rek’lis has played sic is known throughout the world-class performers per- at numerous venues through- area as the next best thing to forming a wide range of enter- out the area. With over 60 visiting the Emerald Isle. tainment hosted at Cranmore years combined experience Arts Jubilee’s outdoor festi- Mountain, North Conway. they are known to please the val concerts are found at the Music that has stood the crowd with an eclectic mix of base of the North Slope at test of time will take the spot- 80’s, punk rock and new wave Cranmore Mountain in North light on Thursday, Aug. -

By Keane Southard Program Notes

An Appalachian Trail Symphony: New England (Symphony No. 1) by Keane Southard Program notes: An Appalachian Trail Symphony: New England (Symphony No. 1) for Orchestra was begun during my hike of the 734-mile New England portion of the Appalachian Trail (June 11, 2016-August 26, 2016) and completed in late March 2017. The symphony was commissioned by a consortium of orchestras throughout New England in celebration of the 80th anniversary of the completion of the trail, which stretches over approximately 2,200 miles from Springer Mountain in Georgia to Mount Katahdin in Maine. I grew up in central Massachusetts, but a few years before I was born my father was a graduate student at Dartmouth College in Hanover, NH, through which the Appalachian Trail runs after it crosses the Connecticut River from Vermont into New Hampshire. (I actually composed the majority of the symphony in Hanover, with the AT lying only a few hundred feet away in the woods.) They loved living in New Hampshire, and when my siblings and I were young they took us on so many camping and weekend trips around New Hampshire and Vermont. These trips instilled in me a love of the outdoors and this region as well as made me aware of the AT itself. While we didn't do much hiking on those trips, I was captivated by the idea of one day hiking this legendary trail. When I later started to get serious about composing, I thought it would be wonderful to hike the trail and then write a piece of music about the experience some day. -

In This Issue: Saturday, November 3 Highland Center, Crawford Notch, NH from the Chair

T H E O H A S S O C I A T I O N 17 Brenner Drive, Newton, New Hampshire 03858 The O H Association is former employees of the AMC Huts System whose activities include sharing sweet White Mountain memories. 2018 Fall Reunion In This Issue: Saturday, November 3 Highland Center, Crawford Notch, NH From the Chair .......... 2 Poetry & Other Tidbits .......... 3 1pm: Hike up Mt. Avalon, led by Doug Teschner (meet Fall Fest Preview .......... 4 at Highland Center Fastest Known Times (FKTs) .......... 6 3:30-4:30pm: Y-OH discussion session led by Phoebe “Adventure on Katahdin” .......... 9 Howe. Be part of the conversation on growing the OHA Cabin Photo Project Update .......... 10 younger and keeping the OHA relevant in the 21st 2019 Steering Committee .......... 11 century. Meet in Thayer Hall. OHA Classifieds .......... 12 4:30-6:30pm: Acoustic music jam! Happy Hour! AMC “Barbara Hull Richardson” .......... 13 Library Open House! Volunteer Opportunities .......... 16 6:30-7:30pm: Dinner. Announcements .......... 17 7:45-8:30pm: Business Meeting, Awards, Announce- Remember When... .......... 18 ments, Proclamations. 2018 Fall Croos .......... 19 8:30-9:15pm: Featured Presentation: “Down Through OHA Merchandise .......... 19 the Decades,” with Hanque Parker (‘40s), Tom Deans Event News .......... 20 (‘50s), Ken Olsen (‘60s), TBD (‘70s), Pete & Em Benson Gormings .......... 21 (‘80s), Jen Granducci (‘90s), Miles Howard (‘00s), Becca Obituaries .......... 22 Waldo (‘10s). “For Hannah & For Josh” .......... 24 9:15-9:30pm: Closing Remarks & Reminders Trails Update .......... 27 Submission Guidelines .......... 28 For reservations, call the AMC at 603-466-2727. Group # 372888 OH Reunion Dinner, $37; Rooms, $73-107. -

Pemigewasset River Draft Study Report, New Hampshire

I PEMIGEWASSET Wil.D AND SCENIC RIVER STUDY DRAFT REPORT MARCH 1996 PEMIGl:WASSl:T WilD AND SCENIC RIVER STUDY M.iU!C:H 1996 Prepared by: New England System Support Office National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior 15 State Street Boston, MA 02109 @ Printed on recycled paper I TABLE OF CONTENTS I o e 1.A The National Wild and Scenic Rivers Act/13 Proposed Segment Classification l .B Study Background/13 land Cover 1. C Study Process/ 14 Zoning Districts 1 .D Study Products/16 Public lands Sensitive Areas e 0 2.A Eligibilily and Classification Criteria/21 2.B Study Area Description/22 A. Study Participants 2.C Free-flowing Character/23 B. Pemigewasset River Management Plan 2.D Outstanding Resource Values: C. Draft Eligibilily and Classification Report Franconia Notch Segment/23 D. Town River Conservation Regulations 2.E Outstanding Resource Values: Valley Segment/24 E. Surveys 2.F Proposed Classifications/25 F. Official Correspondenc~ e 3.A Principal Factors of Suitabilily/31 3.B Evaluation of Existing Protection: Franconia Notch Segment/31 3.C Evaluation of Existing Protection: Valley Segment/32 3.D Public Support for River Conservation/39 3.E Public Support for Wild and Scenic Designation/39 3.F Summary of Findings/ 44 0 4.A Alternatives/ 47 4.B Recommended Action/ 48 The Pemigewasset Wild and Scenic River Study Draft Report was edited by Jamie Fosburgh and designed by Victoria Bass, National Park Service. ~----------------------------- - ---- -- ! ' l l I I I l I IPEMIGEWASSET RIVER STUDYI federal laws and regulations, public and private land own ership for conservation purposes, and physical constraints to additional shoreland development. -

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA)

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 10/01/2019 to 12/31/2019 White Mountain National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact White Mountain National Forest Androscoggin Ranger District (excluding Projects occurring in more than one District) R9 - Eastern Region Evans Brook Vegetation - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants In Progress: Expected:01/2020 06/2020 Patricia Nasta Management Project - Forest products Comment Period Public Notice 207-824-2813 EA - Vegetation management 05/15/2019 [email protected] *UPDATED* (other than forest products) Description: Proposed timber harvest using even-aged and uneven-aged management methods to improve forest health, improve wildlife habitat diversity, and provide for a sustainable yield of forest products. Connected road work will be proposed as well. Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=52040 Location: UNIT - Androscoggin Ranger District. STATE - Maine. COUNTY - Oxford. LEGAL - Not Applicable. The proposed units are located between Hastings Campground and Evans Notch along Route 113, and west of Route 113 from Bull Brook north. Peabody West Conceptual - Recreation management Developing Proposal Expected:12/2021 01/2022 Johnida Dockens Proposal Development - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants Est. Scoping Start 11/2019 207-323-5683 EA - Forest products johnida.dockens@usda. - Vegetation management gov (other than forest products) - Road management Description: The Androscoggin Ranger District of the White Mountain National Forest is in the early stages of proposal development for management activities within the conceptual Peabody West area, Coos County, NH. -

6–8–01 Vol. 66 No. 111 Friday June 8, 2001 Pages 30801–31106

6–8–01 Friday Vol. 66 No. 111 June 8, 2001 Pages 30801–31106 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 19:13 Jun 07, 2001 Jkt 194001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4710 Sfmt 4710 E:\FR\FM\08JNWS.LOC pfrm04 PsN: 08JNWS 1 II Federal Register / Vol. 66, No. 111 / Friday, June 8, 2001 The FEDERAL REGISTER is published daily, Monday through SUBSCRIPTIONS AND COPIES Friday, except official holidays, by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, PUBLIC Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Register Act (44 U.S.C. Subscriptions: Ch. 15) and the regulations of the Administrative Committee of Paper or fiche 202–512–1800 the Federal Register (1 CFR Ch. I). The Superintendent of Assistance with public subscriptions 512–1806 Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402 is the exclusive distributor of the official edition. General online information 202–512–1530; 1–888–293–6498 Single copies/back copies: The Federal Register provides a uniform system for making available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Paper or fiche 512–1800 Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and Assistance with public single copies 512–1803 Executive Orders, Federal agency documents having general FEDERAL AGENCIES applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published Subscriptions: by act of Congress, and other Federal agency documents of public interest. Paper or fiche 523–5243 Assistance with Federal agency subscriptions 523–5243 Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Federal Register the day before they are published, unless the issuing agency requests earlier filing. -

APRIL 2011 Newsletter DARTMOUTH COLLEGE CLASS of 1981

APRIL 2011 newsLetteR DARTMOUTH COLLEGE CLASS OF 1981 Newsletter Editors: Peter Oudheusden • [email protected] • Robert Goldbloom • [email protected] Bill Burgess Elected Trustee Voting for this year’s Alumni Trustee position took place from March 9th through April 6th. REVEL•REFLECT•RECONNECT As Bill was running unopposed - it came as no surprise that he won in a landslide. He will join our other trustee-classmate, Annette Gordon-Reed, who took her seat in February. DARTMOUTH CLASS OF 1981 If you haven’t met Bill, here is a nice write-up the College supplied for interested J u n e 1 6 - 1 9, 2 0 1 1 • Hanover, New Hampshir e alums: “At Dartmouth, Bill was respected Our 30th Reunion is just two months away. It’s time to make sure you are registered, your for leading with inclusivity, enthusiasm reunion housing is booked, your travel plans have been made, and you’ve contacted all of and dedication. He was president of Alpha your friends - this is a great long weekend filled with events, food and catching Delta fraternity, served as president of the up. You don’t want to miss it! Check out our free reunion dedicated smart Interfraternity Council was a member of phone app (found on the class website - www.alum.dartmouth.org/classes/81). Sphinx senior society, Green Key and of It gives you instant access to: registration, housing, weekend schedule, who’s the rugby, football and lacrosse teams. Bill attending (updated daily), a countdown till important weekend events, hotel earned his MBA degree at Harvard and links, local up-to-the-minute weather, a reunion map with the key locations for has nearly three decades of experience in our events, webcams to see the College and the area, and a Dartmouth College corporate finance and venture capital. -

The Transmission the Dartmouth Class of 1968 Newsletter Fall 2014

TheThe Dartmouth Dartmouth Class Class of of 1968 1968 The Transmission The Dartmouth Class of 1968 Newsletter Fall 2014 Class Officers Editor’s Note President: Peter M. Fahey 225 Middle Neck Rd Port Washington, NY 11050 (516) 883-8584, [email protected] There is much exciting news to celebrate from the College this fall. We have just Vice President: John Isaacson beaten Penn, Yale, and Holy Cross in football! It’s nice to pick up the Boston Globe 81 Washington Avenue and read something positive about the College for a change. Having just attended Cambridge, MA 02140 (617) 262-6500 X1827, Class Officers Weekend in early September, there is much support for and excite- [email protected] ment about Moving Dartmouth Forward and the Presidential Steering Committee Secretary: David B. Peck, Jr. will continue to gather input through the fall. As your Newsletter Editor and class- 54 Spooner St. Plymouth, MA 02360 mate, I am encouraged to see this real effort go forward to combat the three ex- (508) 746-5894, [email protected] treme behaviors of sexual assault, high-risk drinking, and exclusivity. President Treasurer: D. James Lawrie, M.D. Hanlon and Dartmouth are national leaders in working to solve these serious prob- 1458 Popinjay Drive Reno, NV 89509 lems that affect most colleges and universities. Unfortunately, Dartmouth has (775) 826 -2241 [email protected] been singled out in the past for these issues and the bad publicity has discouraged students from applying and some from attending once accepted. 50th Reunion Gift: William P.