White Mountain National Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scanned Using Book Scancenter Flexi

Fiftk Annual Report OF THE -New Hampskire Timkerland Owners Association II NINETEEN HUNDRED AND FIFTEEN S«cretary-Treasurer’s Report Balance from 1914.................................... $ 255 33 Assessment (%c)..................................... 7,053 33 Sale Deer Mt. Lookout Station................ 238 00 OFFICERS W. R. Brown, President, Berlin Mills Co. $7,546 66 expenditures L. S. Tainter, Vice-President, Publishers Paper Co. Patrol........................................................ $6,059 27 Morrison, W. H. Secretary-Treasurer, Telephone Repairs.................. 101 04 Gorham, N. H. Exchange and Tolls................................. 86 23 Advertising............................................... 25 00 Salary September and October............... 200 00 DIRECTORS Traveling Expense................................... 92 23 Office Expense........................................ i07 55 W. R. Brown, Berlin Mills Co. Miscellaneous Expense........................... 27 75 L? S. Tainter, Publishers Paper Co. C. C. Wilson, Odell Manufacturing Co. $6,699 07 Balance...................................................... 847 59 E. E. Amey, International Paper Co. Due account unpaid assessments........... 5 25 H. G. Philbrook, Connecticut Valley Co. $852 84 The number of members belonging to the Association this season is thirty-two, and the total acreage owned by them is 930,540 acres. The weather conditions having been so unusu ally favorable the past season it has been possible' a to limit the total assessment to three-fourths cents per acre, as in 1914. The Conway Lumber Company and the Pub lishers Paper Company have paid assessments the The 1915 Fire Season past season on the lands purchased of them by the Owing to the very early spring, a number of Federal Government as the transaction had not the Patrolmen had to be employed much earlier been completed, thereby making the acreage of the than in 1914. -

Dry River Wilderness

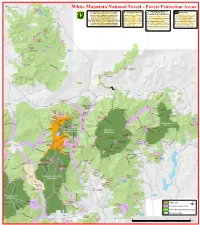

«¬110 SOUTH White Mountain National Forest - Forest Protection Areas POND !5 !B Forest Protection Areas (FPAs) are geographic South !9 Designated Sites !9 The Alpine Zone Wilderness Pond areas where certain activities are restricted to A Rarity in the Northeast Rocky prevent overuse or damage to National Forest Designated sites are campsites or Wilderness Areas are primitive areas Pond resources. Restrictions may include limits on picnic areas within a Forest The alpine zone is a high elevation area in with few signs or other developments. !B camping, use of wood or charcoal fires and Protection area where otherwise which trees are naturally absent or stunted Trails may be rough and difficult to maximum group size. FPAs surround certain features prohibited activities (camping at less that eight feet tall. About 8 square follow. Camping and fires are gererally miles of this habitat exists in the prohibited within 200 feet of any trail W (trails, ponds, parking areas, etc) with either a 200-foot and/or fires) may occur. These e s or ¼ mile buffer. They are marked with signs sites are identified by an official Northeast with most of it over 4000 feet unless at a designated site. No more t M as you enter and exit so keep your eyes peeled. sign, symbol or map. in elevation. Camping is prohibited in the than ten people may occupy a single i la TYPE Name GRID n alpine zone unless there is two or more campsite or hike in the same party. Campgrounds Basin H5 feet of snow. Fires are prohibited at all Big Rock E7 !B Blackberry Crossing G8 ROGERS times. -

New Hampshirestate Parks M New Hampshire State Parks M

New Hampshire State Parks Map Parks State State Parks State Magic of NH Experience theExperience nhstateparks.org nhstateparks.org Experience theExperience Magic of NH State Parks State State Parks Map Parks State New Hampshire nhstateparks.org A Mountain Great North Woods Region 19. Franconia Notch State Park 35. Governor Wentworth 50. Hannah Duston Memorial of 9 Franconia Notch Parkway, Franconia Historic Site Historic Site 1. Androscoggin Wayside Possibilities 823-8800 Rich in history and natural wonders; 56 Wentworth Farm Rd, Wolfeboro 271-3556 298 US Route 4 West, Boscawen 271-3556 The timeless and dramatic beauty of the 1607 Berlin Rd, Errol 538-6707 home of Cannon Mountain Aerial Tramway, Explore a pre-Revolutionary Northern Memorial commemorating the escape of Presidential Range and the Northeast’s highest Relax and picnic along the Androscoggin River Flume Gorge, and Old Man of the Mountain plantation. Hannah Duston, captured in 1697 during peak is yours to enjoy! Drive your own car or take a within Thirteen Mile Woods. Profile Plaza. the French & Indian War. comfortable, two-hour guided tour on the 36. Madison Boulder Natural Area , which includes an hour Mt. Washington Auto Road 2. Beaver Brook Falls Wayside 20. Lake Tarleton State Park 473 Boulder Rd, Madison 227-8745 51. Northwood Meadows State Park to explore the summit buildings and environment. 432 Route 145, Colebrook 538-6707 949 Route 25C, Piermont 227-8745 One of the largest glacial erratics in the world; Best of all, your entertaining guide will share the A hidden scenic gem with a beautiful waterfall Undeveloped park with beautiful views a National Natural Landmark. -

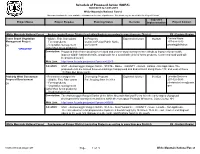

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA)

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 10/01/2019 to 12/31/2019 White Mountain National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact White Mountain National Forest Androscoggin Ranger District (excluding Projects occurring in more than one District) R9 - Eastern Region Evans Brook Vegetation - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants In Progress: Expected:01/2020 06/2020 Patricia Nasta Management Project - Forest products Comment Period Public Notice 207-824-2813 EA - Vegetation management 05/15/2019 [email protected] *UPDATED* (other than forest products) Description: Proposed timber harvest using even-aged and uneven-aged management methods to improve forest health, improve wildlife habitat diversity, and provide for a sustainable yield of forest products. Connected road work will be proposed as well. Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=52040 Location: UNIT - Androscoggin Ranger District. STATE - Maine. COUNTY - Oxford. LEGAL - Not Applicable. The proposed units are located between Hastings Campground and Evans Notch along Route 113, and west of Route 113 from Bull Brook north. Peabody West Conceptual - Recreation management Developing Proposal Expected:12/2021 01/2022 Johnida Dockens Proposal Development - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants Est. Scoping Start 11/2019 207-323-5683 EA - Forest products johnida.dockens@usda. - Vegetation management gov (other than forest products) - Road management Description: The Androscoggin Ranger District of the White Mountain National Forest is in the early stages of proposal development for management activities within the conceptual Peabody West area, Coos County, NH. -

White Mountains of New Hampshire PO Box 10 • Rte. 112 / Kancamagus Highway • North Woodstock, New Hampshire, USA 03262 W

MOUN E T T A I I N H S White Mountains of New Hampshire PO Box 10 • Rte. 112 / Kancamagus Highway • North Woodstock, New Hampshire, USA 03262 W N E E W IR H HAMPS contact: Kate Wetherell, [email protected], or call 603-745-8720 | VisitWhiteMountains.com TAKE A TRAIN RIDE The Conway Scenic and Hobo Railroads offer scenic excursions along the river and through the valley. The Mt. Washington Cog Railway offers locomotive rides to the top of Mt. Washington, New England’s highest peak. At Clark’s Trading Post, ride across the world’s only Howe-Truss railroad covered bridge. DISCOVER NATURE At The Flume Gorge, discover Franconia Notch through a free 20 minute High Definition DVD about the area. Enjoy scenic nature walks, PEI stroll along wooden boardwalks and marvel at glacial gorges and boulder caves at Lost River Gorge and Polar Caves Park. TIA TO CONNECTICUT LAKES TO DIXVILLE NOTCH LANCASTER O BERLIN A SC 3 2 CONNECTICUT RIVER Halifax 135 D 16 SANTA’S VILLAGE WHITEFIELD 116 MOUNT WASHINGTON VA JEFFERSON GORHAM A LITTLETON PRESIDENTIAL RANGE 2 3 2 AINE 18 M 93 NO 115 N BETHLEHEM MT. WASHINGTON 16 eal A 95 302 93 302 TWIN MOUNTAIN AUTO ROAD NEW HAMPSHIRE FRANCONIA MOUNT Montr C 302 WASHINGTON LISBON 117 3 WILDCAT Yarmouth COG RAILWAY MOUNTAIN 10 CANNON MOUNTAIN FRANCONIA RANGE AERIAL TRAMWAY PINKHAM NOTCH BATH FRANCONIA NOTCH APPALACHIAN CRAWFORD NOTCH rtland 116 WHITE MOUNTAIN MOUNTAIN CLUB Po 93 STATE PARK 89 112 KINSMAN NOTCH VERMON NATIONAL FOREST JACKSON THE FLUME GORGE LOST RIVER WHALE'S TALE CRAWFORD NOTCH GORGE and WATER PARK STORY LINCOLN BARTLETT GLEN LAND 93 BOULDER CAVES CLARK’S LOON MOUNTAIN RESORT TRADING POST ALPINE ADVENTURES The White Mountains Trail 302 HOBO RAILROAD ATTITASH 112 25 NORTH A National Scenic Byway MOUNTAIN NORTH W 91 WOODSTOCK RESORT CONWAY o NE PASSACONAWAY T 93 CONWAY CRANMORE 81 anchester MOUNTAIN ront M oston KANCAMAGUS HIGHWAY SCENIC RAILROAD ORK B 118 RESORT To Y 25C WARREN 16 ASS. -

Street • North Conway Village (Across from Joe Jones) • 356-5039 “Life Is Good”

VOLUME 33, NUMBER 8 JULY 10, 2008 FREE THE WEEKLY NEWS & LIFESTYLE JOURNAL OF MT. WASHINGTON VALLEY All Eight in ’08: Steve Caming visits Carter Notch Hut, the first of the eight AMC huts he plans to explore this summer … A 6 Alpine Disc Golf: Wildcat Ski Area offers a new, lift-serviced, attraction for the summer A 15 Arts Jubilee Begins 26th Season: This summer’s lineup of outdoor entertainment begins July 17 … B1 As The Wheels Turn: Hundreds of bicyclists will be gathering in Fryeburg for the Maine Jackson, NH 03846 • Lodging: 383-9443 • Recreation: 383-0845 Bike Rally … www.nestlenookfarm.com • 1-800-659-9443 B16 A SALMON PRESS PUBLICATION • (603) 447-6336 • PUBLISHED IN CONWAY, NH SSTTOORRYY LLAANNDD On Second Thought CC OO RR NN EE RR The tradition Down for now - Up again in 2010 continues at... Jackson’s Trickey Barn continues its journey By Steven Caming Jackson Grammar School students is touchstone and community rallying Contributing Writer also being produced and will be available point in Jackson and like an old friend, IT WAS A DAY OF CELEBRA- locally. will not be forgotten until it can be seen tion, remembrance and excitement as Somehow, this old barn has become a again. ▲ more than 75 Jackson residents gathered recently to witness the ceremonial Where there's a smile & beginning of the dismantling process of Jackson’s most historic barn. The adventure around every corner! Trickey Barn was built 150 years ago and has stood in the center of the village since then. New this summer The morning’s activities included three parts: a ribbon unfurling across the at Story Land barn doors, which officially sealed the barn. -

Download It FREE Today! the SKI LIFE

SKI WEEKEND CLASSIC CANNON November 2017 From Sugarbush to peaks across New England, skiers and riders are ready to rock WELCOME TO SNOWTOPIA A experience has arrived in New Hampshire’s White Mountains. grand new LINCOLN, NH | RIVERWALKRESORTATLOON.COM Arriving is your escape. Access snow, terrain and hospitality – as reliable as you’ve heard and as convenient as you deserve. SLOPESIDE THIS IS YOUR DESTINATION. SKI & STAY Kids Eat Free $ * from 119 pp/pn with Full Breakfast for Two EXIT LoonMtn.com/Stay HERE Featuring indoor pool, health club & spa, Loon Mountain Resort slopeside hot tub, two restaurants and more! * Quad occupancy with a minimum two-night Exit 32 off I-93 | Lincoln, NH stay. Plus tax & resort fee. One child (12 & under) eats free with each paying adult. May not be combined with any other offer or discount. Early- Save on Lift Tickets only at and late-season specials available. LoonMtn.com/Tickets A grand new experience has arrived in New Hampshire’s White Mountains. Arriving is your escape. Access snow, terrain and hospitality – as reliable as you’ve heard and as convenient as you deserve. SLOPESIDE THIS IS YOUR DESTINATION. SKI & STAY Kids Eat Free $ * from 119 pp/pn with Full Breakfast for Two EXIT LoonMtn.com/Stay HERE Featuring indoor pool, health club & spa, Loon Mountain Resort slopeside hot tub, two restaurants and more! We believe that every vacation should be truly extraordinary. Our goal Exit 32 off I-93 | Lincoln, NH * Quad occupancy with a minimum two-night stay. Plus tax & resort fee. One child (12 & under) is to provide an unparalleled level of service in a spectacular mountain setting. -

Ski NH 4-Season Press Kit? This Press Kit Highlights Story Ideas, Photos, Videos and Contact Information for Media Relations People at Each Ski Area

4-SEASON PRESS KIT We're not just winter. The New Hampshire experience spans across all four seasons. 4-SEASON PRESS KIT Story Ideas for Every Season Ski NH's new 4-Season Press Kit was created to help provide media professionals with story ideas about New Hampshire's ski areas for all seasons. This is a living document, for the most up-to-date press kit information as well as links to photos visit the links on this page: https://www.skinh.com/about-us/media. For press releases visit: https://www.skinh.com/about-us/media/press-releases. What is the Ski NH 4-Season Press Kit? This press kit highlights story ideas, photos, videos and contact information for media relations people at each ski area. This new-style press kit offers much more for media than contact lists and already- published resort photos, it offers unique ski area story ideas in one convenient location--covering all seasons. As this is a working document, more ski areas are being added weekly. Visit the links above for the most up-to-date version. Enjoy, Shannon Dunfey-Ball Marketing & Communications Manager Shannon @SkiNH.com Are you interested in exploring New Hampshire's ski area offerings? Email Shannon with your media inquiries and she will help you make the connections you need. WWW.SKINH.COM Winter 2019-20 Media Kit Welcome to Loon Mountain Resort, New England’s most- Loon also offers plenty of exciting four-season activities, accessible mountain destination. Located in New Hampshire’s including scenic gondola rides, downhill mountain biking, White Mountains two hours north of Boston, Loon has been in summit glacial caves, ziplines and climbing walls, to name a few. -

Exhibit B White Mountain National Forest

72°00'00" 71°52'30" 71°45'00" 71°37'30" 71°30'00" 71°22'30" 71°15'00" 71°07'30" 71°00'00" 70°52'30" 70°45'00" 72°15'00" 72°07'30" 72°00'00" ERROL 11 MILES S T R A T F O R D Victor NORTH STRATFORD 8 MILES Head Bald Mtn PIERMONT 4.6 MI. Jimmy Cole 2378 16 /(3 Ledge Ä( 10 Hill Ä( 1525 D U M M E R Dummer Cem Potters 44° Sunday Hill Mtn Ledge 44° 37' Blackberry 1823 Percy 37' 25A 30" Dame Hill Ä( Ä(110 30" SOUTHERN APPALACHIAN Cem Morse Mtn Dickey Bickford 1925 Airstrip Hill Crystal Hill Beach 2067 25A Hill 65 Cummings 25A Ä( Mt Cube 110 TRAIL CORRIDOR Ä( Orfordville 2909 Devils Mtn Ä(A 1209 O R O FO R D 110 Moore Slide Ä( Mtn 43° TRAIL Groveton 1700 SOUTH Location ST. JOHNSBERRY 44 MI. Strawberry 43° Stark Hill 52' HEXACUBA POND West Milan Closton Hill "!9 Covered Bridge 1843 30" 52' 110 Hill !t A Peabody Covered Bridge 30" Mill Mtn Ä( Hill CO Quinttown GILMANSMI. CORNER 0.6 Substa 2517 10 Bundy CO 110 Ä( Kenyon Mountain Eastman Ledges Ä( Hill 2665 S T A R K Horn Hill Hill Stonehouse 2055 Jodrie MILAN HILL Mountain 11 91 Brick Hill Milan Hol 1986 110 ¦¨§ Cem Milan Hill B North Mousley Ä( Lookout 1737 Thetford Mountain 2008 Cape Horn MILAN HILL Skunk Lampier /(5 STATE PARK Moody Hill TRAIL M I L A N Mountain Northumberland North Square Smith Mtn Hardscrabble 1969 Peak Green Post Hill Mountain 2735 Ledge 2213 Beech NANSEN 3 Hutchins 2804 Rogers ORANGE /( Hill Mtn Ledge SKI JUMP GRAFTON The Pinnacle Smarts Hodgoon UNKNOWN 3500 Lookout "!9 Mountain N O R T H U M B E R L A N D 3730 Hill Demmick HIll 2909 ROGERS LEDGE Round < MILL Acorn 1583 ! Mtn THETFORD 0.7 MI. -

Speckled Mountain Heritage Hikes Bickford Brook and Blueberry Ridge Trails – 8.2-Mile Loop, Strenuous

Natural Speckled Mountain Heritage Hikes Bickford Brook and Blueberry Ridge Trails – 8.2-mile loop, strenuous n the flanks and summit of Speckled Mountain, human and natural history mingle. An old farm Oroad meets a fire tower access path to lead you through a menagerie of plants, animals, and natural communities. On the way down Blueberry Ridge, 0with0.2 a sea 0.4 of blueberry 0.8 bushes 1.2 at 1.6 your feet and spectacular views around every bend, the rewards of the summit seem endless. Miles Getting There Click numbers to jump to descriptions. From US Route 2 in Gilead, travel south on Maine State Route 113 for 10 miles to the parking area at Brickett Place on the east side of the road. From US Route 302 in Fryeburg, travel north on Maine State Route 113 for 19 miles to Brickett Place. 00.2 0.4 0.8 1.2 1.6 Miles A House of Many Names -71.003608, 44.267292 Begin your hike at Brickett Place Farm. In the 1830s, a century before present-day Route 113 sliced through Evans Notch, John Brickett and Catherine (Whitaker) Brickett built this farmhouse from home- made bricks. Here, they raised nine children alongside sheep, pigs, cattle, and chick- ens. Since its acquisition by the White Mountain National Forest in 1918, Brickett Place Farmhouse has served as Civilian Conservation Corps headquarters (1930s), Cold River Ranger Station (1940s), an Appalachian Mountain Club Hut (1950s), and a Boy Scouts of America camp (1960-1993). Today, Brickett Place Farmhouse has gone through a thorough restoration and re- mains the oldest structure in the eastern region of the Forest Service. -

Amc Cold River Camp

AMC COLD RIVER CAMP NORTH CHATHAM, NEW HAMPSHIRE Winter 2018 ◊ Number 37 www.amccoldrivercamp.org 44 ˚ 14’ 10.1” N 71 ˚ 0’ 42.8” W CHAIRMAN’S WELCOME Dover, New Hampshire, January 2018 Dear Cold River Camp community, ctober 27, 2017. Needle ice. Those exquisite, fragile crystalline columns of ice that grow out of the ground when conditions are right – mois- Oture-saturated unfrozen dirt and the air temperature below freezing. Beth and I were headed up the A-Z and Mount Tom Spur trails to the Mount Tom summit. Not much of a view to be had up there, but what a special hike! A couples miles of trail whose sides were strewn with oodles of patches and swaths of needle ice. A fairyland of sorts. You just never know what treasure the next hike will reveal. July 1, 2018. That day will mark the one hundred years duration of Cold River Camp’s operation serving guests as an Appalachian Mountain Club facility. Imagine that! All the guest footsteps walking our same trails. All the conver- sations at meals. The songs, poems and skits evoked and shared on Talent Nights. And volunteer-managed all that time. It is marvelous that so many of our CRC community carry on that tradition of committed investment. But we’ll hold our enthusiasm in check and do our celebrating in our 100th anniversary year, which will be 2019. A celebration committee has been at hard at work for about two years. You can read more about that on page 18 of this LDD. -

Building a Sustainable Natural Resource-Based Economy

Blaine House Conference on Maine’s Natural Resource-based Industry: Charting a New Course November 17, 2003 onference Report With recommendations to Governor John E. Baldacci Submitted by the Conference Planning Committee Richard Barringer and Richard Davies, Co-chairs February 2004 . Acknowledgements The following organizations made the conference possible with their generous contributions: Conference Sponsors The Betterment Fund Finance Authority of Maine LL Bean, Inc. Maine Community Foundation US Fish and Wildlife Service US Forest Service This report was compiled and edited by: Maine State Planning Office 38 State House Station Augusta, ME 04333 (207) 287-3261 www.maine/gov/spo February 2004 Printed under Appropriation #014 07B 3340 2 . Conference Planning Committee Richard Barringer, Co-chair, Richard Davies, Co-chair Professor, Muskie School of Public Service, Senior Policy Advisor, Governor Office USM Dann Lewis Spencer Apollonio Director, Office of Tourism, DECD Former Commissioner, Dept of Marine Resources Roland D. Martin Commissioner, Dept of Inland Fisheries and Edward Bradley Wildlife Maritime Attorney Patrick McGowan Elizabeth Butler Commissioner, Dept of Conservation Pierce Atwood Don Perkins Jack Cashman President, Gulf of Maine Research Institute Commissioner, Dept of Economic and Community Development Stewart Smith Professor, Sustainable Agriculture Policy, Charlie Colgan UMO Professor, Muskie School of Public Service, USM Robert Spear Commissioner, Dept of Agriculture Martha Freeman Director, State Planning Office