White Mountain National F Orest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Spring 2012 Resuscitator — the Camp, Joan Bishop Was a Counselor, and Brooks Van Mudgekeewis Camp for Girls Everen Was a Cook

T H E O H A S S O C I A T I O N 17 Brenner Drive, Newton, New Hampshire 03858 The O H Association is former employees of the AMC Huts System whose activities include sharing sweet White Mountain memories Save the Dates 2012 Details to email later and on website May 19, Cabin Spring Reunion Prepay seafood $30, $15 current croo and kids under 14. Non-seafood is $12, $10 for croo & kids. 12:00 lunch; 4:00 lobster dinner. Walk ins-no lobster. Email Moose Meserve at [email protected] and mail check to 17 Brenner Drive, Newton, NH 03858 Gala, May 22-24 Hut croo training session GreenWool Blanket Vinnie Night, August 18 End of season croo party, Latchstring Award by Caroline Collins I October 10-12, I keep a green wool blanket in the back of my car. It’s Cabin Oktoberfest faded and tattered, but the white AMC logo is still visible. Traditional work for Bavarian victuals feast I tied it to my packboard the last time I hiked out of Carter Email Moose Meserve at [email protected] Notch Hut in the early ’90s. This summer I visited the AMC that you are coming to plan the provisions huts in the White Mountains of New Hampshire after a 22 year absence. My first experience with the Appalachian November 3, Fallfest Mountain Club was whitewater canoeing lessons in Pennsyl- Annual Meeting at vania when I was in high school. My mother was struck with Highland Center inspiration and the next thing I knew we were packing up Details to come camping equipment, canoes and kayaks, and exploring the Potomac, the Shenandoah, the Lehigh, and the Nescopeck rivers among others. -

2016 Annual Results 603-889-0652 •

EXCELLENCE EMPOWERMENT INNOVATION 2016 ANNUAL RESULTS 603-889-0652 • WWW.PLUSCOMPANY.ORG 19 Chestnut Street 3 Ballard Way, Unit #302 885 Main Street, Unit #5 Nashua, NH 030603 Lawrence, MA 01840 Tewksbury, MA 01876 603-889-0652 978-689-8829 978-640-3936 DONNALEE LOZEAU 2016 SANDY GARRITY AWARD WINNER Donnalee Lozeau was elected the 55th Mayor of Nashua in November 2007, and was elected to serve a second term in November 2011. After serving 8 years, she decided to return to the Southern New Hampshire Services (SNHS), a non-profit agency where she previously worked for 15 years. She currently serves as Executive Director of SNHS which is a Community Action Agency serving Hillsborough and Rockingham Counties. One of Donnalee’s greatest strengths is being able to inspire change. She has always used her connections within the community to help create key friendships that lead to improvement and long lasting partnerships. Donnalee had a pivotal role in creating the partnership between St. Joseph Hospital and Project SEARCH, which is a school-to-work program that provides employment and education opportunities to individuals with cognitive and physical disabilities. Project Search began in 2008 and has had 8 graduating classes since. Out of the 54 individuals who have completed the program, 46 of them have gone on to obtain successful careers. Donnalee attends every Project SEARCH graduation that she can, saying she is inspired by hearing the graduates speak and “hearing from them in their own words, the things that light them up.” She shared that once she had to miss a graduation, and she decided to invite the entire class to come to the mayor’s office instead so she could speak with each graduate personally. -

' Committee on Environment and Natural

’ PO Box 164 - Greenville Junction, ME 04442 Testimony Before the Committee on Environment and Natural Resources on LD 901, HP 0629 An Act to Amend the Laws Governing the Determination of a Wind Energy Development's Efiect on the Scenic Character of Maine’s Special Places March 23, 2017 Senator Saviello, Representative Tucker, Distinguished Members of the Committee: My name is Christopher King, I live in Greenville, and I am Secretary of the Moosehead Region Futures Committee (MRFC), a Maine non-profit corporation, which has been active in shaping the Moosehead Lake Region's future development for more than a decade. I wish to testify in favor of LD 901, and to urge the Committee to adopt certain amendments to this bill. Specifically, the MRFC requests that the Committee amend LD 901, by adding to the language proposed in Section 3 (35-A MRSA §3452, sub-§4), paragraph B, the following subparagraphs: {Q} Big Moose Mountain in Piscataquis County; and ('7) Mount Kineo in Piscataquis County. MRFC TESTIMONY ow LD 901 BEFORE ENR COMMIITEE - 3/23/2017 - PAGE 1 OF 3 The purpose of LD 901 is to extend the protections granted by the Legislature in 35-A MRSA §3452 to Maine’s scenic resources of state or national significance (SRSNS), defined with precision in 35-A MRSA §3451 (9), to certain SRSNSs which are situated between 8 and 15 miles from a proposed wind energy development’s generating facilities. Currently, the Department of Environmental Protection “shall consider insignificant the effects of portions of [a wind energy] development’s generating facilities located more than 8 miles...from a [SRSNS].” 35-A MRSA §3452 (3). -

Dry River Wilderness

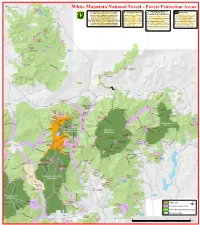

«¬110 SOUTH White Mountain National Forest - Forest Protection Areas POND !5 !B Forest Protection Areas (FPAs) are geographic South !9 Designated Sites !9 The Alpine Zone Wilderness Pond areas where certain activities are restricted to A Rarity in the Northeast Rocky prevent overuse or damage to National Forest Designated sites are campsites or Wilderness Areas are primitive areas Pond resources. Restrictions may include limits on picnic areas within a Forest The alpine zone is a high elevation area in with few signs or other developments. !B camping, use of wood or charcoal fires and Protection area where otherwise which trees are naturally absent or stunted Trails may be rough and difficult to maximum group size. FPAs surround certain features prohibited activities (camping at less that eight feet tall. About 8 square follow. Camping and fires are gererally miles of this habitat exists in the prohibited within 200 feet of any trail W (trails, ponds, parking areas, etc) with either a 200-foot and/or fires) may occur. These e s or ¼ mile buffer. They are marked with signs sites are identified by an official Northeast with most of it over 4000 feet unless at a designated site. No more t M as you enter and exit so keep your eyes peeled. sign, symbol or map. in elevation. Camping is prohibited in the than ten people may occupy a single i la TYPE Name GRID n alpine zone unless there is two or more campsite or hike in the same party. Campgrounds Basin H5 feet of snow. Fires are prohibited at all Big Rock E7 !B Blackberry Crossing G8 ROGERS times. -

Research Natural Areas on National Forest System Lands in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Utah, and Western Wyoming: a Guidebook for Scientists, Managers, and Educators

USDA United States Department of Agriculture Research Natural Areas on Forest Service National Forest System Lands Rocky Mountain Research Station in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, General Technical Report RMRS-CTR-69 Utah, and Western Wyoming: February 2001 A Guidebook for Scientists, Managers, and E'ducators Angela G. Evenden Melinda Moeur J. Stephen Shelly Shannon F. Kimball Charles A. Wellner Abstract Evenden, Angela G.; Moeur, Melinda; Shelly, J. Stephen; Kimball, Shannon F.; Wellner, Charles A. 2001. Research Natural Areas on National Forest System Lands in Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Utah, and Western Wyoming: A Guidebook for Scientists, Managers, and Educators. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-69. Ogden, UT: U.S. Departmentof Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 84 p. This guidebook is intended to familiarize land resource managers, scientists, educators, and others with Research Natural Areas (RNAs) managed by the USDA Forest Service in the Northern Rocky Mountains and lntermountain West. This guidebook facilitates broader recognitionand use of these valuable natural areas by describing the RNA network, past and current research and monitoring, management, and how to use RNAs. About The Authors Angela G. Evenden is biological inventory and monitoring project leader with the National Park Service -NorthernColorado Plateau Network in Moab, UT. She was formerly the Natural Areas Program Manager for the Rocky Mountain Research Station, Northern Region and lntermountain Region of the USDA Forest Service. Melinda Moeur is Research Forester with the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain ResearchStation in Moscow, ID, and one of four Research Natural Areas Coordinators from the Rocky Mountain Research Station. J. Stephen Shelly is Regional Botanist and Research Natural Areas Coordinator with the USDA Forest Service, Northern Region Headquarters Office in Missoula, MT. -

New Hampshirestate Parks M New Hampshire State Parks M

New Hampshire State Parks Map Parks State State Parks State Magic of NH Experience theExperience nhstateparks.org nhstateparks.org Experience theExperience Magic of NH State Parks State State Parks Map Parks State New Hampshire nhstateparks.org A Mountain Great North Woods Region 19. Franconia Notch State Park 35. Governor Wentworth 50. Hannah Duston Memorial of 9 Franconia Notch Parkway, Franconia Historic Site Historic Site 1. Androscoggin Wayside Possibilities 823-8800 Rich in history and natural wonders; 56 Wentworth Farm Rd, Wolfeboro 271-3556 298 US Route 4 West, Boscawen 271-3556 The timeless and dramatic beauty of the 1607 Berlin Rd, Errol 538-6707 home of Cannon Mountain Aerial Tramway, Explore a pre-Revolutionary Northern Memorial commemorating the escape of Presidential Range and the Northeast’s highest Relax and picnic along the Androscoggin River Flume Gorge, and Old Man of the Mountain plantation. Hannah Duston, captured in 1697 during peak is yours to enjoy! Drive your own car or take a within Thirteen Mile Woods. Profile Plaza. the French & Indian War. comfortable, two-hour guided tour on the 36. Madison Boulder Natural Area , which includes an hour Mt. Washington Auto Road 2. Beaver Brook Falls Wayside 20. Lake Tarleton State Park 473 Boulder Rd, Madison 227-8745 51. Northwood Meadows State Park to explore the summit buildings and environment. 432 Route 145, Colebrook 538-6707 949 Route 25C, Piermont 227-8745 One of the largest glacial erratics in the world; Best of all, your entertaining guide will share the A hidden scenic gem with a beautiful waterfall Undeveloped park with beautiful views a National Natural Landmark. -

Moosehead Lake Region Is a Part

Ta) zl\) gd n& u< nO Fil q* m rof,,< E ;1ZC ro5s :D--'r Clo- OE EF >3 J AJ m g- --{ a @ u, E igi- 1-(O az IIl E cl) l\J o$ .) ' f )jsp rrsrisiles gilililfiilffiilililflmill ,r iJ ln ,tl}3*yj.{ls ;'lJ $ i ir i,;, j:t;*ltj*,$.tj Display until September 30 I Maine's Moosohcad Lake Challenging hikes pay off with spectacular views ! by Dale Dunlop o 6 o M il t,:"t'yffi *#: i#ft [F,Tl#nr[.I But a discerning few, in search a different type of vacation, head for the Great North Woods, of which the Moosehead Lake region is a part. Located deep in the Maine Highlands region, Moosehead is the largest lake in Maine and one of the largest natural lakes in the eastern United States. lts irregular shores are surrounded by mountains on all sides, including Mount Kineo's 232-meIre (760{oot) cliffs that plunge directly into the water. lt is a deep lake, known for its world-class brook trout, togue (lake trout) and landlocked salmon fisheries. Finally, it is a historic lake that reflects Maine's past as a fur-trading route, a lumbering centre and a tourist destination. On a recent visit, I was able to sample first-hand why this area is so popular with outdoor enthusiasts. Aboriginal people used Moosehead Lake as a gathering spot for thousands of years-padicularly Mount Kineo, where they found a unique form of flint that was applied in tools and weapons up and down the eastern seaboard. -

As Time Passes Over the Land

s Time Passes over theLand A White Mountain Art As Time Passes over the Land is published on the occasion of the exhibition As Time Passes over the Land presented at the Karl Drerup Art Gallery, Plymouth State University, Plymouth, NH February 8–April 11, 2011 This exhibition showcases the multifaceted nature of exhibitions and collections featured in the new Museum of the White Mountains, opening at Plymouth State University in 2012 The Museum of the White Mountains will preserve and promote the unique history, culture, and environmental legacy of the region, as well as provide unique collections-based, archival, and digital learning resources serving researchers, students, and the public. Project Director: Catherine S. Amidon Curator: Marcia Schmidt Blaine Text by Marcia Schmidt Blaine and Mark Green Edited by Jennifer Philion and Rebecca Chappell Designed by Sandra Coe Photography by John Hession Printed and bound by Penmor Lithographers Front cover The Crawford Valley from Mount Willard, 1877 Frank Henry Shapleigh Oil on canvas, 21 x 36 inches From the collection of P. Andrews and Linda H. McLane © 2011 Mount Washington from Intervale, North Conway, First Snow, 1851 Willhelm Heine Oil on canvas, 6 x 12 inches Private collection Haying in the Pemigewasset Valley, undated Samuel W. Griggs Oil on canvas, 18 x 30 inches Private collection Plymouth State University is proud to present As Time Passes over the about rural villages and urban perceptions, about stories and historical Land, an exhibit that celebrates New Hampshire’s splendid heritage of events that shaped the region, about environmental change—As Time White Mountain School of painting. -

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA)

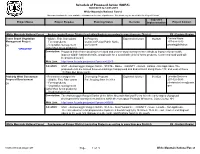

Schedule of Proposed Action (SOPA) 10/01/2019 to 12/31/2019 White Mountain National Forest This report contains the best available information at the time of publication. Questions may be directed to the Project Contact. Expected Project Name Project Purpose Planning Status Decision Implementation Project Contact White Mountain National Forest Androscoggin Ranger District (excluding Projects occurring in more than one District) R9 - Eastern Region Evans Brook Vegetation - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants In Progress: Expected:01/2020 06/2020 Patricia Nasta Management Project - Forest products Comment Period Public Notice 207-824-2813 EA - Vegetation management 05/15/2019 [email protected] *UPDATED* (other than forest products) Description: Proposed timber harvest using even-aged and uneven-aged management methods to improve forest health, improve wildlife habitat diversity, and provide for a sustainable yield of forest products. Connected road work will be proposed as well. Web Link: http://www.fs.usda.gov/project/?project=52040 Location: UNIT - Androscoggin Ranger District. STATE - Maine. COUNTY - Oxford. LEGAL - Not Applicable. The proposed units are located between Hastings Campground and Evans Notch along Route 113, and west of Route 113 from Bull Brook north. Peabody West Conceptual - Recreation management Developing Proposal Expected:12/2021 01/2022 Johnida Dockens Proposal Development - Wildlife, Fish, Rare plants Est. Scoping Start 11/2019 207-323-5683 EA - Forest products johnida.dockens@usda. - Vegetation management gov (other than forest products) - Road management Description: The Androscoggin Ranger District of the White Mountain National Forest is in the early stages of proposal development for management activities within the conceptual Peabody West area, Coos County, NH. -

^ R ^ ^ S . L O N G I S L a N D M O U N T a I N E E R NEWSLETTER of the ADIRONDACK MOUNTAIN CLUB LONG ISLAND CHAPTER NOVEMBER

LONG ISLAND ^r^^s. MOUNTAINEER NEWSLETTER OF THE ADIRONDACK MOUNTAIN CLUB LONG ISLAND CHAPTER NOVEMBER / DECEMBER 1996 ADIRONDACK MOUNTAIN CLUB LONG ISLAND CHAPTER 1995-1996 P^akJ^e/hX^ P<e/K EXECUTIVE COMITTEE PRESIDENT Rich Ehli 735-7363 VICE-PRESIDENT Jem' Kirshman 543-5715 TREASURER Bud Kazdan 549-5015 SECRETARY Nanov Hodson 692-5754 GOVERNOR Herb Coles 897-5306 As I write this, over fifty members and some objective yardstick, I'm afraid GOVERNOR June Fait 897-5306 friends of the chapter are preparing for many of us would be priced out of the BOARD OF DIRECTORS LI-ADK's annual Columbus Day trip to market for outdoor adventure. If you Carol Kazdan 549-5015 Tracy Clark 549-1967 Ann Brosnan 421-3097 Pauline Lavery 627-5605 the Loj. In most years since joining the have thought about attending our week Don Mantell 598-1015 Jem' Licht 797-5729 club ten years ago, I have enjoyed the end outings, go ahead and give it a try - COMMITEE CHAIRS camaraderie of hiking in the High Peaks you really don't know what you're miss CONSERVATION June Fait 897-5306 HOSPITALITY Arlene Scholer 354-0231 with my hardy and fun-loving fellow ing. ^ MEMBERSHIP Joanne Malecki 265-6596 ADKers on what has often been a spec On the eve before our departure for the MOUNTAINEER Andrew Heiz 221-4719 OUTINGS WE NEED A VOLUNTEER tacular fall weekend. Like me, many of Loj, we will be gathering at Bertucci's PROGRAMS Yetta Sokol 433-6561 the trippers to the fall outing are repeat restaurant in Melville for our annual din PUBLICITY Arlene Scholer 354-0231 ers. -

Great Vacation Times at Chocorua Camping Village & Wabanaki Lodge & the Greater Ossipee - Chocorua Mountain Region for Toll-Free Reservations 1-888-237-8642 Vol

Great Vacation Times at Chocorua Camping Village & Wabanaki Lodge & the Greater Ossipee - Chocorua Mountain Region For Toll-Free reservaTions 1-888-237-8642 Vol. 19 No. 1 GPS: 893 White Mountain Hwy, Tamworth, NH 03886 PO Box 484, Chocorua, NH 03817 email: [email protected] Tel. 1-888-BEST NHCampground (1-888-237-8642) or 603-323-8536 www.ChocoruaCamping.com www.WhiteMountainsLodging.com We Trust That You’ll Our Awesome Park! Escape the noisy rush of the city. Pack up and leave home on a get-away adventure! Come join the vacation tradition of our spacious, forested Chocorua Camping Village KOA! Miles of nature trails, a lake-size pond and river to explore by kayak. We offer activities all week with Theme Weekends to keep the kids and family entertained. Come by tent, pop-up, RV, or glamp-it-up in new Tipis, off-the-grid cabins or enjoy easing into full-amenity lodges. #BringTheDog #Adulting Young Couples... RVers Rave about their Families who Camp Together - Experience at CCV Stay Together, even when apart ...often attest to the rustic, lakeside cabins of You have undoubtedly worked long and hard to earn Why is it that both parents and children look forward Wabanaki Lodge as being the Sangri-La of the White ownership of the RV you now enjoy. We at Chocorua with such excitement and enthusiasm to their frequent Mountains where they can enjoy a simple cabin along Camping Village-KOA appreciate and respect that fact; weekends and camping vacations at Chocorua Camping the shore of Moores Pond, nestled in the privacy of a we would love to reward your achievement with the Village—KOA? woodland pine grove. -

2018 White Mountains of Maine

2018 White Mountains of Maine Summit Handbook 2018 White Mountains of Maine Summit Welcome to the 2018 Family Nature Summit! We are thrilled that you have chosen to join us this summer at the Sunday River Resort in the White Mountains of Maine! Whether this is your first time or your fifteenth, we know you appreciate the unparalleled value your family receives from attending a Family Nature Summit. One of the aspects that is unique about the Family Nature Summits program is that children have their own program with other children their own age during the day while the adults are free to choose their own classes and activities. Our youth programs are run by experienced and talented environmental educators who are very adept at providing a fun and engaging program for children. Our adult classes and activities are also taught by experts in their fields and are equally engaging and fun. In the afternoon, there are offerings for the whole family to do together as well as entertaining evening programs. Family Nature Summits is fortunate to have such a dedicated group of volunteers who have spent countless hours to ensure this amazing experience continues year after year. This handbook is designed to help orient you to the 2018 Family Nature Summit program. We look forward to seeing you in Maine! Page 2 2018 White Mountains of Maine Summit Table of Contents Welcome to the 2018 Family Nature Summit! 2 Summit Information 7 Summit Location 7 Arrival and Departure 7 Room Check-in 7 Summit Check-in 7 Group Picture 8 Teacher Continuing Education