The Evolution of Clutch Size and Reproductive Rates in Parasitic Cuckoos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jacobin Cuckoo of Either the Cape Bulbul P

556 Cuculidae: cuckoos and coucals months later. In Botswana, departure time was correlated with total rainfall during the summer, birds being recorded two months later at the end of a wet year than during drought years (Herremans 1994d). Differences between the subspecies in timing of occurrence and different ranges within the region, if any, have not been unravelled. Breeding: It is a brood parasite whose prime hosts are Pycnonotus bulbuls, the Sombre Bulbul Andropadus impor- tunus, and the Fiscal Shrike Lanius collaris (Rowan 1983; Maclean 1993b). Egglaying has been recorded in the region October–April, with a peak November–January (Dean 1971; Irwin 1981; Rowan 1983; Tarboton et al. 1987b; Skinner 1996a; Brown & Clinning in press). The atlas data suggest breeding to be a month later than recorded in the literature, but this results from a bias towards the recording of recently fledged young. Interspecific relationships: Because the distribution map represents both breeding and nonbreeding visitors, it is not straightforward to relate it to the distributions of host species. Breeding was, however, reported from all Zones and it can be deduced that it must use Blackeyed Pycnonotus barbatus and Redeyed P. nigricans Bulbuls extensively as hosts, but there is no distributional evidence for exclusive use Jacobin Cuckoo of either the Cape Bulbul P. capensis or the Sombre Bulbul. Bontnuwejaarsvoël The bulbuls, however, all have parts of their range where the cuckoo does not occur, but least so for the Blackeyed Bulbul. Clamator jacobinus Historical distribution and conservation: It was once quite common in the Cape Peninsula (3418A) but is now only The Jacobin Cuckoo is widespread in the Afrotropical a rare visitor to the southwestern Cape Province (Rowan 1983; savannas, both north and south of the equator (Fry et al. -

Adult Brood Parasites Feeding Nestlings and Fledglings of Their Own Species: a Review

J. Field Ornithol., 69(3):364-375 ADULT BROOD PARASITES FEEDING NESTLINGS AND FLEDGLINGS OF THEIR OWN SPECIES: A REVIEW JANICEC. LORENZANAAND SPENCER G. SEALY Departmentof Zoology Universityof Manitoba Winnipeg,Manitoba R3T 2N2 Canada Abstract.--We summarized 40 reports of nine speciesof brood parasitesfeeding young of their own species.These observationssuggest that the propensityto provisionyoung hasnot been lost entirely in brood parasitesdespite the belief that brood parasiticadults abandon their offspringat the time of laying.The hypothesisthat speciesthat participatein courtship feeding are more likely to provisionyoung was not supported:provisioning of young has been observedin two speciesof brood parasitesthat do not courtshipfeed. The function of this provisioningis unknown, but we suggestit may be: (1) a non-adaptivevestigial behavior or (2) an adaptation to ensure adequatecare of parasiticyoung. The former is more likely the case.Further studiesare required to determinewhether parasiticadults commonly feed their genetic offspring. ADULTOS DE AVES PARAS•TICASALIMENTANDO PICHONES Y VOLANTONES DE SU PROPIA ESPECIE: UNA REVISION Sinopsis.--Resumimos40 informes de nueve especiesde avesparasiticas que alimenaron a pichonesde su propia especie.Las observacionessugieren que la propensividadde alimentar a los pichonesno ha sido totalmente perdida en las avesparasiticas, no empecea la creencia de que los parasiticosabandonan su progenie al momento de poner los huevos.La hipttesis de que las especiesque participan en cortejo de alimentacitn, son milspropensas a alimentar los pichonesno tuvo apoyo.Las observacionesde alimentacitn a pichonesse han hecho en dos especiesparasiticas cuyo cortejo no incluye la alimentacitn de la pareja. La funcitn de proveer alimento se desconoce.No obstante,sugerimos que pueda ser: 1) una conducta vestigialno adaptativa,o 2) una adaptacitn parc asegurarel cuidado adecuadode los pi- chonesparasiticos. -

Polistes Wasps and Their Social Parasites: an Overview

Ann. Zool. Fennici 43: 531–549 ISSN 0003-455X Helsinki 29 December 2006 © Finnish Zoological and Botanical Publishing Board 2006 Polistes wasps and their social parasites: an overview Rita Cervo Dipartimento di Biologia Animale e Genetica, University of Florence, via Romana 17, I-50125 Florence, Italy (e-mail: rita.cervo@unifi.it) Received 10 Dec. 2005, revised version received 29 Nov. 2006, accepted 6 May 2006 Cervo, R. 2006: Polistes wasps and their social parasites: an overview. — Ann. Zool. Fennici 43: 531–549. Severe brood care costs have favoured the evolution of cheaters that exploit the paren- tal services of conspecifics or even heterospecifics in both birds and social insects. In Polistes paper wasps, three species have lost worker castes and are dependent on hosts to produce their sexuals, while other species use hosts facultatively as an alternative to caring for their own brood. This paper offers an overview of the adaptations, strategies and tricks used by Polistes social parasites to successfully enter and exploit host social systems. Moreover, it also focuses on the analogous solutions adopted by the well-known brood parasite birds, and stresses the evolutionary convergence between these two phy- logenetically distant taxa. A comparative analysis of life-history patterns, as well as of phylogenetic relationships of living facultative and obligate parasitic species in Polistes wasps, has suggested a historical framework for the evolution of social parasitism in this group. As with avian brood parasites, the analysis of adaptation and counter adaptation dynamics should direct the future approach for the study of social parasitism in Polistes wasps. -

Does Nest Sanitation Elicit Egg Rejection in an Open‑Cup Nesting Cuckoo Host Rejecter? Tongping Su1,2 , Chanchao Yang2 , Shuihua Chen1* and Wei Liang2*

Su et al. Avian Res (2018) 9:27 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40657-018-0119-4 Avian Research RESEARCH Open Access Does nest sanitation elicit egg rejection in an open‑cup nesting cuckoo host rejecter? Tongping Su1,2 , Chanchao Yang2 , Shuihua Chen1* and Wei Liang2* Abstract Background: Nest sanitation behavior is one of the most important means to ensure high reproductive efciency. In avian brood parasitism, nest sanitation behavior may be a pre-adaptation of host birds that allows them to identify the parasitic eggs, so that egg discrimination behavior may have evolved from nest sanitation behavior. However, whether nest sanitation behavior could improve egg rejection in cuckoo hosts was inconclusive. Methods: In this study, we investigated the relationship between nest sanitation and egg discrimination behavior in a potential cuckoo host, the Brown-breasted Bulbul (Pycnonotus xanthorrhous) with two experimental groups. In the frst group, we added a blue, non-mimetic egg to the nest of the host, while in the second group we added a blue, non-mimetic egg and a peanut half-shell. Results: The results showed that in the frst group, the probability of rejecting the non-mimetic eggs was 53.8% (n 26 nests). In comparison, all of the Brown-breasted Bulbuls in the second group were able to rapidly remove the peanut= shells from the nest, but only 52.6% (n 19 nests) rejected the non-mimetic eggs. The rejection rates of the non-mimetic eggs in both experimental groups= were not signifcantly diferent. Conclusions: Our study indicated that nest sanitation behavior of Brown-breasted Bulbuls did not infuence their egg recognition and that egg discrimination ability of Brown-breasted Bulbuls was not directly related to nest sanita- tion behavior. -

Why Cuckoos Should Parasitize Parrotbills by Laying Eggs Randomly

Yang et al. Avian Research (2015) 6:5 DOI 10.1186/s40657-015-0014-1 REVIEW Open Access Why cuckoos should parasitize parrotbills by laying eggs randomly rather than laying eggs matching the egg appearance of parrotbill hosts? Canchao Yang1, Fugo Takasu2, Wei Liang1* and Anders P Møller3 Abstract The coevolutionary interaction between cuckoos and their hosts has been studied for a long time, but to date some puzzles still remain unsolved. Whether cuckoos parasitize their hosts by laying eggs randomly or matching the egg morphs of their hosts is one of the mysteries of the cuckoo problem. Scientists tend to believe that cuckoos lay eggs matching the appearance of host eggs due to selection caused by the ability of the hosts to recognize their own eggs. In this paper, we first review previous empirical studies to test this mystery and found no studies have provided direct evidence of cuckoos choosing to parasitize host nests where egg color and pattern match. We then present examples of unmatched cuckoo eggs in host nests and key life history traits of cuckoos, e.g. secretive behavior and rapid egg-laying and link them to cuckoo egg laying behavior. Finally we develop a conceptual model to demonstrate the egg laying behaviour of cuckoos and propose an empirical test that can provide direct evidence of the egg-laying properties of female cuckoos. We speculate that the degree of egg matching between cuckoo eggs and those of the host as detected by humans is caused by the ability of the hosts to recognize their own eggs, rather than the selection of matching host eggs by cuckoos. -

Bird Surveys in the Gamba Complex of Protected Areas, Gabon

Bird Surveys in the Gamba Complex of Protected Areas, Gabon George ANGEHR1, Brian SCHMIDT2, Francis NJIE3, Patrice CHRISTY4, Christina GEBHARD2, Landry TCHIGNOUMBA5 and Martin A.E. OMBENOTORI6 1 Introduction status of protected areas within the complex was revised, and two areas, Loango and Moukalaba- Approximately 2,100 species of birds are known from Doudou, were upgraded to National Parks. An analy- Africa south of the Sahara. Gabon is fairly well known sis by BirdLife International (Christy 2001) found the ornithologically, the first collections having been made Gamba Complex to qualify as one of Gabon’s six by du Chaillu as early as the 1850s. To date, 678 Important Bird Areas (IBAs). Important Bird Areas species have been recorded in the country (Christy are areas that have been determined to be most impor- 2001), or about 30% of the total known for sub- tant for the conservation of birds at the global level, Saharan Africa. Gabon’s bird diversity is relatively lim- based on the distribution of endangered, endemic, ited compared to some other Afrotropical countries, habitat-restricted, and congregatory species. such as Cameroon, which has more than 900 species. Despite its importance, there has been relatively lit- The main factors involved include its relatively small tle published ornithological work on the Gamba size and lack of habitat and topographic diversity. The Complex. Sargeant (1993) was resident at Gamba for natural vegetation of most of Gabon is lowland ever- five years and compiled a bird list for the immediate green and semi-evergreen forest, with only limited area, and as well as lists for other localities within the areas of savanna in the east and south, and its maxi- Complex, including Rabi, the Rembo (River) Ndogo, mum elevation is 1,575 m, compared to 4,095 m for and the east side of the Moukalaba Faunal Reserve, Cameroon. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G. Phd, Mphil, Dclinpsychol) at the University of Edinburgh

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Organisation & Development of Anti-Predator Behaviour in a Cooperative Breeder James R.S. Westrip Supervised by: Dr. Matthew Bell (principal supervisor) and Dr. Per Smiseth A thesis submitted in application for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy from The University of Edinburgh, School of Biological Sciences 2016 Author’s Declaration I, James R.S. Westrip, declare that; a) this thesis has been composed by myself, and b) either that the work is my own, or, where I have been a member of a research group, that I have made a substantial contribution to the work, such contribution being clearly indicated, and c) that the work has not been submitted for any other degree or professional qualification except as specified, and d) any included publications are my own work, except where indicated throughout the thesis, and summarised and clearly identified below*. -

Namibia, Okavango & Victoria Falls Overland II 2015

Namibia, Okavango and Victoria Falls Overland II 23rd March to 9th April 2015 (18 days) African Scops Owl by Heinz Ortmann Trip report compiled by tour leader: Heinz Ortmann Trip Report RBT NBZ II 2015 2 Our incredible journey through the scenic and breath-taking landscapes and natural areas of Namibia, Botswana and southern Zambia began on a rather warm afternoon at the Livingstone sewage ponds. Not surprisingly, these ponds provided us with great views of several species of waterbirds including the lovely Long-toed and African Wattled Lapwings, well over 100 Glossy Ibis, Grey-headed Gull, Whiskered Tern and Squacco Heron to name just a few. Shorebirds were well represented with the dainty Three-banded Plover accompanied by some Palearctic migrants in the form of Little Stint and Wood Sandpiper. Black Crakes boldly marched along the water’s edge and, over the swathe of water hyacinth that seemingly choked parts of the pond, whilst African Rail was more difficult and provided us with only brief views of a single bird. One of the ponds even had a resident Nile Crocodile that we managed to see quite well! Within and atop the reeds we found Red- faced Cisticola singing noisily, Lesser Swamp and Sedge Warblers crept along the edge and made their presence known through various songs and contact calls as they busily foraged within their preferred habitat. A little way from the water, in the surrounding vegetation, Jacobin Cuckoo, White- winged Widowbird, Village Weaver, Southern Red Bishop and Red-billed Quelea all showed well. European Bee-eaters, Marabou Stork, Brown Snake Eagle and Hooded Vulture each, at some point during our time at the ponds, was observed flying overhead. -

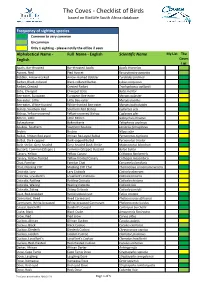

Checklist of Birds Based on Birdlife South Africa Database

The Coves - Checklist of Birds based on BirdLife South Africa database Frequency of sighting species Common to very common Uncommon Only 1 sighting - please notify the office if seen Slegs 1 waarneming - stel asb die kantoor in kennis Alphabetical Name - Full Name - English Scientific Name My List The English Coves List Apalis, Bar-throated Bar-throated Apalis Apalis thoracica 2 Avocet, Pied Pied Avocet Recurvirostra avosetta 2 Babbler, Arrow-marked Arrow-marked Babbler Turdoides jardineii 4 Barbet, Black-collared Black-collared Barbet Lybius torquatus 5 Barbet, Crested Crested Barbet Trachyphonus vaillantii 5 Batis, Chinspot Chinspot Batis Batis molitor 2 Bee-eater, European European Bee-eater Merops apiaster 1 Bee-eater, Little Little Bee-eater Merops pusillus 1 Bee-eater, White-fronted White-fronted Bee-eater Merops bullockoides 4 Bishop, Southern Red Southern Red Bishop Euplectes orix 5 Bishop, Yellow-crowned Yellow-crowned Bishop Euplectes afer 1 Bittern, Little Little Bittern Ixobrychus minutus 1 Bokmakierie Bokmakierie Telophorus zeylonus 1 Boubou, Southern Southern Boubou Laniarius ferrugineus 5 Brubru Brubru Nilaus afer 1 Bulbul, African Red-eyed African Red-eyed Bulbul Pycnonotus nigricans 1 Bulbul, Dark-capped Dark-capped Bulbul Pycnonotus tricolor 4 Bush-shrike, Grey-headed Grey-headed Bush-Shrike Malaconotus blanchoti 3 Buzzard, Common (Steppe ) Common (Steppe) Buzzard Buteo buteo 1 Canary, Yellow Yellow Canary Crithagra flaviventris 1 Canary, Yellow-fronted Yellow-fronted Canary Crithagra mozambica 3 Chat, Familiar Familiar -

Ecology and Evolution of Nest Parasitism in Indian Cuckoo

Nature Environment and Pollution Technology ISSN: 0972-6268 Vol. 14 No. 4 pp. 847-853 2015 An International Quarterly Scientific Journal General Research Paper Ecology and Evolution of Nest Parasitism in Indian Cuckoo R. K. Sharma*†, A. K. Goyal* and Manju Sharma** *Department of Zoology, Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra-136 119, India **Department of Zoology, KVA DAV College for Women, Karnal-132 001, India †Corresponding author: R. K. Sharma ABSTRACT Nat. Env. & Poll. Tech. Website: www.neptjournal.com Nest parasitism is a common phenomenon in many species of birds in which a female of one species lays Received: 8-9-2014 her eggs in the nest of another species to be hatched and cared by the hosts. The nest parasitism evolved Accepted: 13-10-2014 initially as a facultative strategy to use the nest of one species which has raised its brood or deserted nests and then further advanced into parasitism. The host species feed on a wide spectra of food resources, Key Words: especially rich in protein and are insectivores, carnivores or omnivores in contrast to the very restrictive Nest parasitism feeding habits of the parasite species. Parasitism cost for the host is often high which favour the evolution of Brood parasitism host defence leading to a parallel evolution between adaptation and counter adaptation of host-parasite Nest ecology interaction. The understanding of breeding biology and ecology of nest parasitism provides important Indian cuckoo information for the population management of host and parasitic species to devise very specialized conservation strategies for the delicate interaction in the quickly evolving environmental scenario. -

Kenya: the Coolest Trip in Africa, May 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Kenya: The Coolest Trip in Africa, May 2016 Kenya: The Coolest Trip in Africa 12-28 May 2016 TOUR LEADER: Adam Scott Kennedy Report and photos by Adam Scott Kennedy Gray Crowned Crane in Nairobi National Park Kenya is a mind-blowing birding destination at any time of year but it would seem that our May departure was especially well-timed. Not only did we enjoy the best weather imaginable but we arrived in time to see a majority of resident birds in full breeding plumage, intra-African migrants just arriving and we even caught the tail-end of the Palearctic migration. This classic set departure tour covered a vast array of habitats to be found within Kenya, from the verdant Guinea-Congolese rainforest at Kakamega and the Afro-montane forests of Mount Kenya, the very full Rift Valley lakes and papyrus swamps of Lake Victoria, to the endless plains of the Masai Mara. In total, we recorded 413 bird species of which 398 were seen and 15 were ‘heard only’. In addition, we observed 43 mammal species and 10 reptiles were also noted. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Kenya: The Coolest Trip in Africa, May 2016 12th May Tom and Suzanne negotiated Kenya customs with diplomatic acuity and were promptly delivered to the Boma Inn by Joseph. After a much needed drink, we turned in for the night and began to dream of what was to come… 13th May The group rendezvoused in the small garden of the Boma Inn for a first taste of African bird life. -

Visual Trickery in Avian Brood Parasites

CHAPTER 6 Visual trickery in avian brood parasites N aomi E . L angmore and C laire N . S pottiswoode 6. 1 Introduction into rearing its young. Thus we generally see the most advanced parasite recognition systems Visual mimicry is a strategy deployed by a wide amongst hosts of evicting parasites, which in turn range of taxa, from spiders that mimic the ants they select for highly accurate visual mimicry by para- hunt ( Nelson and Jackson 2006 ), to cross-dressing sites to evade host detection. males in bluegill sunfi sh ( Dominey 1980 ), and However, host defenses are not the only selective harmless snakes that mimic the vibrant colors of agent responsible for the evolution of visual mimicry venomous snakes ( Harper and Pfenning 2008 ) (see in brood parasites. Mimicry can also arise to facilitate Chapter 11 ). Although visual mimicry is wide- exploitation of parent–offspring channels of commu- spread amongst invertebrates, and to a lesser extent nication, ensuring that the parasite chick is able to fi sh, amphibians, and reptiles ( Ruxton et al. 2004 ), elicit adequate care from its foster parents (parasite it is generally a rare phenomenon among birds (but “tuning,” Davies 2011 ). Mimicry for this purpose is see e.g., Dumbacher and Fleischer 2001 ). However, equally likely to arise in evicting and non-evicting the avian brood parasites provide a notable excep- parasites, and was termed sequential evolution mim- tion. Several recent fi eld studies, combined with icry by Grim ( 2005 ), to distinguish it from mimicry new techniques for quantifying mimicry and mod- that arises through a coevolutionary arms race.