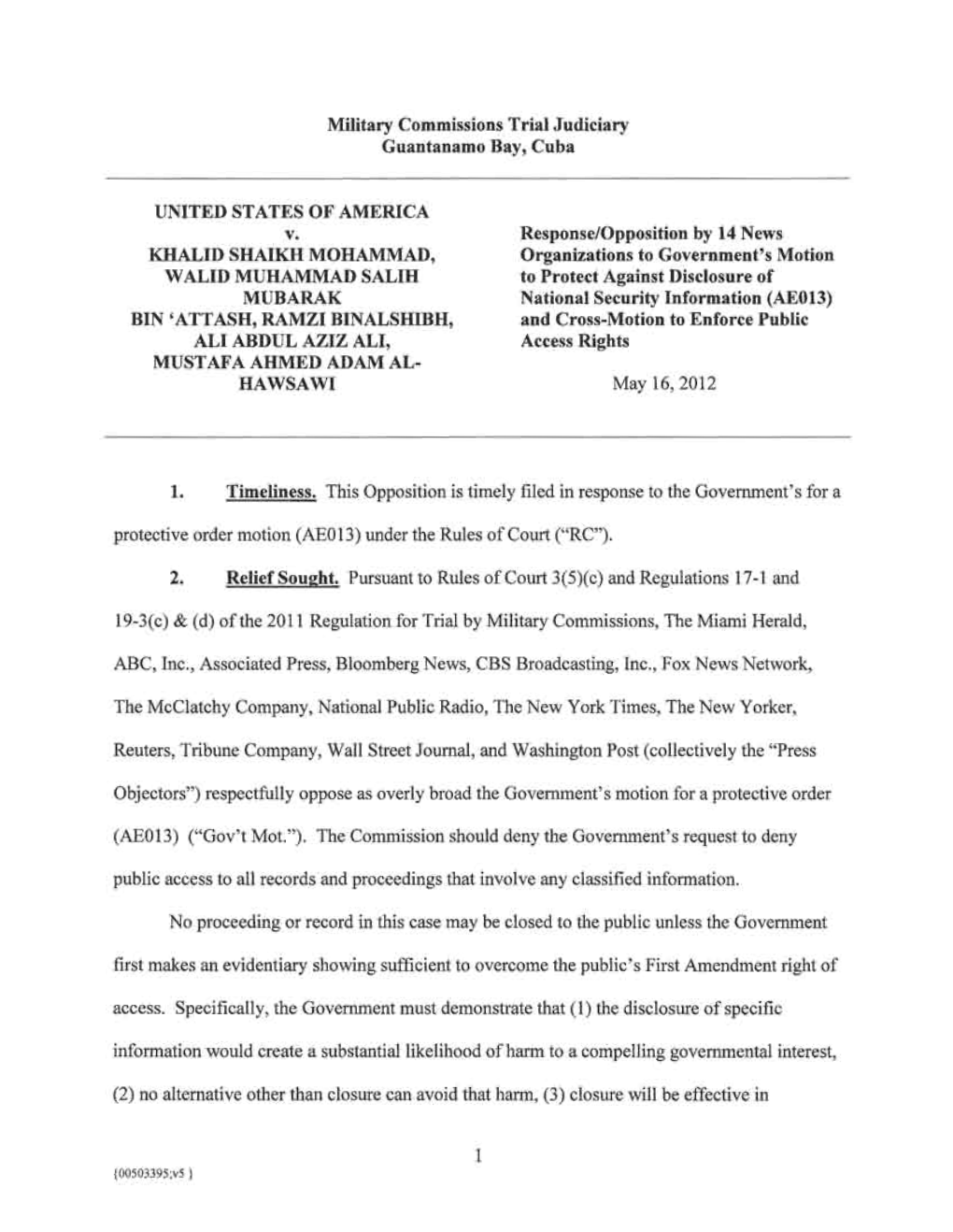

Military Commissions Trial Judiciary Guantanamo Bay, Cuba UNITED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Domestic Investigation Into Participation of Polish

XXXI POLISH YEARBOOK OF IN TER NA TIO NAL LAW 2011 PL ISSN 0554-498X Adam Bodnar, Irmina Pacho* DOMESTIC INVESTIGATION INTO PARTICIPATION OF POLISH OFFICIALS IN THE CIA EXTRAORDINARY RENDITION PROGRAM AND THE STATE RESPONSIBILITY UNDER THE EUROPEAN CONVENTION ON HUMAN RIGHTS Abstract Poland has been accused of participation in the extraordinary rendition program established by the United States after the September 11, 2001 attacks. It is believed that a secret CIA detention facility operated on the Polish territory, where terrorist suspects were transferred, detained and interrogated with the use of torture. Currently, Poland has found itself in a unique situation, since, unlike in other countries, criminal investigation into renditions and human right violations is still pending. Serious doubts have arisen, however, as to the diligence of the proceedings. The case was incomprehen- sibly prolonged by shifting the investigation to diff erent prosecutors. Its proper conduct was hindered due to state secrecy and national security provisions, which have covered the entire investigation from the beginning. This article argues that Polish judicial au- thorities, along with the government, should undertake all actions aiming at explaining the truth about extraordinary rendition and seeking accountability for human rights infringement. Otherwise, Poland may face legal responsibility for violating the European Convention on Human Rights. This scenario becomes very probable, since one of the * Adam Bodnar, Ph.D., is the Vice-president of the Board and head of the le- gal department of the Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights, Warsaw; he is also an as- sociate professor in the Human Rights Chair of the Faculty of Law, Warsaw University. -

We Tortured Some Folks’ the Wait for Truth, Remedy and Accountability Continues As Redaction Issue Delays Release of Senate Report on Cia Detentions

USA ‘WE TORTURED SOME FOLKS’ THE WAIT FOR TRUTH, REMEDY AND ACCOUNTABILITY CONTINUES AS REDACTION ISSUE DELAYS RELEASE OF SENATE REPORT ON CIA DETENTIONS Amnesty International Publications First published in September 2014 by Amnesty International Publications International Secretariat Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom www.amnesty.org Copyright Amnesty International Publications 2014 Index: AMR 51/046/2014 Original Language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers. Amnesty International is a global movement of 3 million people in more than 150 countries and territories, who campaign on human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights instruments. We research, campaign, advocate and mobilize to end abuses of human rights. Amnesty International is independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion. Our work is largely financed by contributions from our membership and donations Table of contents ‘We tortured some folks’ ................................................................................................ 1 ‘I understand why it happened’ ...................................................................................... -

Application No. 28761/11 Abd Al Rahim Hussayn Muhammad AL NASHIRI Against Poland Lodged on 6 May 2011

FOURTH SECTION Application no. 28761/11 Abd Al Rahim Hussayn Muhammad AL NASHIRI against Poland lodged on 6 May 2011 STATEMENT OF FACTS 1. The applicant, Mr Abd Al Rahim Hussayn Muhammad Al Nashiri, is a Saudi Arabian national of Yemeni descent, who was born in 1965. He is currently detained in the Internment Facility at the US Guantanamo Bay Naval Base in Cuba. The applicant is represented before the Court by Mr J.A. Goldston, attorney, member of the New York Bar and Executive Director of the Open Society Justice Initiative (“the OSJI”), Mr R. Skilbeck, barrister, member of the England and Wales Bar and Litigation Director of the OSJI, Ms A. Singh, attorney, member of the New York Bar and Senior Legal Officer at the OSJI, and also by Ms N. Hollander, attorney, member of the New Mexico Bar. A. Background 1. USS Cole bombing in 2000 2. On 12 October 2000 a suicide terrorist attack on the United States Navy destroyer USS Cole took place in Aden, Yemen when the ship stopped in the Aden harbour for refuelling. It was attacked by a small bomb- laden boat. The explosion opened a 40 foot hole in the warship, killing 17 American sailors and injuring 40 personnel. The applicant, considered to have been one of the most senior figures in al’Qaeda, has been the prime suspect in the 2000 bombing. He has been suspected of masterminding and orchestrating the attack (see also paragraph 55 below). 2 AL NASHIRI v. POLAND – STATEMENT OF FACTS AND QUESTIONS 2. MV Limburg bombing 3. -

Strafanzeige

Dritter (thermonuklearer) Weltkrieg droht! 1 Hiermit wird Strafanzeige g e g e n Herrn Gerhard Fritz Kurt Schröder, geb. am 07.04.1944 in Mossenberg im Kreis Lippe Herrn Joseph Martin Fischer, geb. am 12.04.1948 in Gerabronn Herrn Guido Westerwelle, geb. am 27.12.1961 in Bad Honnef Herrn Frank-Walter Steinmeier, geb. am 05. Januar 1956 in Detmold Frau Dr. Angela Dorothea Merkel (geb. Kasner), geb. am 17.07.1954 in Hamburg wegen des dringenden Verdachts der Autorisierung von Kriegsverbrechen gemäß der Regelungen des Völkerstrafgesetzbuches und Tötungsverbrechen gemäß des Strafgesetzbuches der BRD sowie der Beihilfe/Duldung von Aggressionskriegen vom Territorium der Bundesrepublik Deutschland aus in Afghanistan, Irak, Libyen und der Duldung/Beihilfe des Einsatzes von Kampfdrohnen der in Deutschland stationierten US-Streitkräfte in Pakistan, Somalia, Afghanistan, Jemen und weiteren Staaten sowie der Befürwortung von Waffenlieferungen an Staaten, die Aggressionskriege führen oder geführt haben und an Staaten, die anderen Völkerrechtssubjekten Aggressionshandlungen androhen und aller darüber hinaus in Frage kommenden Straftatbestände. Vorwort Nie wieder Krieg von deutschem/europäischen Boden aus war und ist eine unumstößliche Lehre aus den zwei verheerenden Weltkriegen des 20. Jahrhunderts. Dennoch unterhält die Bundesrepublik heute eine der schlagkräftigsten Armeen und ist integraler Bestandteil der NATO als ein aktiv global agierendes Militärbündnis mit dem Anspruch, der stetigen territorialen Ausdehnung durch die Aufnahme/Integration immer weiterer Staaten Bei objektiver Betrachtung und Analyse der global agierenden Wirtschaftsblöcke/- zentren ist zu konstatieren, dass seit mehreren Jahrzehnten ein verheerender globaler Finanz- und Währungskrieg zwischen einzelnen Staaten/Staatengruppen geführt wird, primär um die Vormachtstellung des US – Dollars gegen konkurrierende Währungen sowie ein Cyber- und Wirtschaftskrieg mit fatalen volkswirtschaftlichen Folgen für eine Vielzahl von Staaten. -

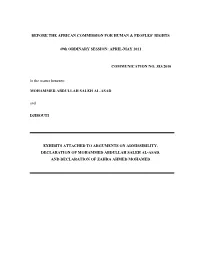

Exhibits Attached to Arguments on Admissibility, Declaration of Mohammed Abdullah Saleh Al-Asad, and Declaration of Zahra Ahmed Mohamed

BEFORE THE AFRICAN COMMISSION FOR HUMAN & PEOPLES’ RIGHTS 49th ORDINARY SESSION: APRIL-MAY 2011 COMMUNICATION NO. 383/2010 In the matter between: MOHAMMED ABDULLAH SALEH AL-ASAD and DJIBOUTI EXHIBITS ATTACHED TO ARGUMENTS ON ADMISSIBILITY, DECLARATION OF MOHAMMED ABDULLAH SALEH AL-ASAD, AND DECLARATION OF ZAHRA AHMED MOHAMED EXHIBITS The United Republic of Tanzania Departure Declaration Card, 27 December 2003…….A Center for Human Rights and Global Justice, On the Record: U.S. Disclosures on Rendition, Secret Detention, and Coercive Interrogation (New York: NYU School of Law, 2008)………………………………………………………………………………..B Letter to the Attorney General of Djibouti, 31 March 2009…….….…..…….…….….…C United Nations Human Rights Council, 13th Session, Joint Study on Global Practices in Relation to Secret Detention in the Context of Countering Terrorism, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/13/42 (19 February 2010)………………………………………………………. D Republic v. Director of Immigration Services, ex parte Mohammed al-Asad (Habeas Corpus petition), High Court of Tanzania, 17 June 2004………………………………...E Amnesty International, United States of America: Below the radar- Secret flights to torture and ‘disappearance,’ 5 April 2006……………………………………………….F Prepared Remarks of Treasury Secretary John Snow to Announce Joint U.S. and Saudi Action Against Four Branches of Al-Haramain in the Financial War on Terror, JS-1107, 22 January 2004…………………………………………………………………………..G Henry Lyimo, Guardian (Dar es Salaam), Yemenis, Italians Expelled, 30 December 2003…………………………………………………………………………………...….H Roderick Ndomba, Daily News (Dar es Salaam), Dar Deports 2,367 Aliens, 30 December 2003……...……………………………..………………………………………………….I International Committee of the Red Cross, ICRC Report on the Treatment of Fourteen “High Value Detainees” in CIA Custody, 2007…………………………..……….……...J International Seismological Centre Earthquake Data…………………………………….K U.S. -

CIA Torture Unredacted: Chapter

APPENDIX 1 CHAPTER 1 UNREDACTING CIA TORTURE CHAPTER 1: CHAPTER 1 UNREDACTING CIA TORTURE CHAPTER 2 Much has been written about the CIA torture programme, and its broad contours are now well understood. Referred to by the CIA as the Rendition, Detention and Interrogation (RDI) pro- gramme, it ran from September 2001 until January 2009, and formed a central plank of the Bush administration’s ‘War on Terror’. It was global in scope, and shocking in its depravity, representing one of the most profoundly disturbing episodes of recent US and allied foreign policy. The pro- gramme resulted in multiple violations of domestic and international law, encompassing a global network of kidnap operations, indefinite secret detention at numerous locations, and the sys- CONCLUSION tematic use of brutal interrogation techniques which clearly amounted to torture. As part of the programme, scores of terror suspects were swept up by the CIA in the months and years after 9/11, with capture operations taking place across Europe, Africa, the Caucasus, the Middle East, and Central, South and Southeast Asia. Foreign security forces often played a role in the capture, either jointly with the CIA or acting on the basis of US and allied intelligence. Prisoners were held for days or weeks in foreign custody, and were often interrogated under torture. CIA officials were present during many of these interrogations. For example, Majid al- APPENDIX 1 Maghrebi (#91) was held in Pakistani custody for several weeks before his transfer to a CIA prison in Afghanistan. Throughout this period, he was interrogated and tortured repeatedly, including many times via electric shocks until he lost consciousness, as well as beatings (including with a leather whip) and the use of stress positions and positional torture (including tying him to a frame and ‘stretching’ him). -

Ngo S in Terrorism Cases: Diffusing Norms of International Human Rights Law

Chapter 21 ngo s in Terrorism Cases: Diffusing Norms of International Human Rights Law Jeffrey Davis 1 Introduction – Abu Zubaydah On 28 March 2002, American and Pakistani agents stormed a house in Faisalabad, Pakistan, firing their weapons as they sought to capture men they believed were senior Al Qaeda operatives. They shot Abu Zubaydah in the groin, thigh and stomach, nearly killing him. cia agents took Abu Zubaydah that day and disappeared him into a web of secret prisons and torture for the next four years.1 Shortly after his arrest us officials rendered Abu Zubaydah to a secret detention facility in Thailand. There fbi agents who knew Arabic and who had experience questioning Al Qaeda members interrogated him. Abu Zubaydah told them he wished to cooperate and quickly turned over information the fbi agents referred to as ‘important’ and ‘vital.’2 When Abu Zubaydah’s med- ical condition deteriorated, agents moved him to a hospital for treatment, and even helped with his recuperation. At that moment, the cia decided to introduce the first elements of its enhanced interrogation techniques. As the fbi interrogators stated, ‘we have obtained critical information regarding Abu Zubaydah thus far and have now got him speaking about threat information … we have built tremendous report [sic]with Abu Zubaydah.’ ‘Now that we are on the eve of “regular” interviews to get threat information,’ they complained, ‘we have been “written out” of future interviews.’3 Soon after the cia took over Abu Zubaydah’s interrogation, agents blind- folded him, strapped him to a stretcher and flew him to the Stare Kiejkuty base in Szymany, Poland. -

Historical Dictionary of International Intelligence Second Edition

The historical dictionaries present essential information on a broad range of subjects, including American and world history, art, business, cities, countries, cultures, customs, film, global conflicts, international relations, literature, music, philosophy, religion, sports, and theater. Written by experts, all contain highly informative introductory essays on the topic and detailed chronologies that, in some cases, cover vast historical time periods but still manage to heavily feature more recent events. Brief A–Z entries describe the main people, events, politics, social issues, institutions, and policies that make the topic unique, and entries are cross- referenced for ease of browsing. Extensive bibliographies are divided into several general subject areas, providing excellent access points for students, researchers, and anyone wanting to know more. Additionally, maps, pho- tographs, and appendixes of supplemental information aid high school and college students doing term papers or introductory research projects. In short, the historical dictionaries are the perfect starting point for anyone looking to research in these fields. HISTORICAL DICTIONARIES OF INTELLIGENCE AND COUNTERINTELLIGENCE Jon Woronoff, Series Editor Israeli Intelligence, by Ephraim Kahana, 2006. Russian and Soviet Intelligence, by Robert W. Pringle, 2006. Cold War Counterintelligence, by Nigel West, 2007. World War II Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2008. Sexspionage, by Nigel West, 2009. Air Intelligence, by Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey, 2009. Middle Eastern Intelligence, by Ephraim Kahana and Muhammad Suwaed, 2009. German Intelligence, by Jefferson Adams, 2009. Ian Fleming’s World of Intelligence: Fact and Fiction, by Nigel West, 2009. Naval Intelligence, by Nigel West, 2010. Atomic Espionage, by Glenmore S. Trenear-Harvey, 2011. Chinese Intelligence, by I. C. -

New Evidence of Torture Prison in Poland

ﺓﻱﻡﺍﻝﺱﺇﻝﺍ ﺓﺝﻭﻝﻑﻝﺍ ﺕﺍﻱﺩﺕﻥﻡ - New Evidence of Torture Prison in Poland al-faloja‘s English < ::: ﺓﻡﺍﻉﻝﺍ ﺕﺍﻱﺩﺕﻥﻡﻝﺍ ::: < ﺓﻱﻡﺍﻝﺱﺇﻝﺍ ﺓﺝﻭﻝﻑﻝﺍ ﺕﺍﻱﺩﺕﻥﻡ ؟ﺕﺍﻥﺍﻱﺏﻝﺍ ﻅﻑﺡ ﻭﺽﻉﻝﺍ ﻡﺱﺍ Section ﺭﻭﺭﻡﻝﺍ ﺓﻡﻝﻙ New Evidence of Torture Prison in Poland ﻡﻱﻭﻕﺕﻝﺍ ﺕﺍـــﻡﻱﻝﻉﺕﻝﺍ ﻉﻭﺽﻭﻡﻝﺍ ﺽﺭﻉ ﻉﺍﻭﻥﺍ ﻉﻭﺽﻭﻡﻝﺍ ﺕﺍﻭﺩﺃ ﻡﻭﻱ 6 ﺫﻥﻡ #1 :ﺕﺍﻙﺭﺍﺵﻡﻝﺍ alhambra 677 ﺩﻩﺕﺝﻡ ﻭﺽﻉ New Evidence of Torture Prison in Poland as salamu alaikum wa rahmatullahi wa barakatu here is another very intersting and revealing article about the torture business created by the american regime and how european countries have been involved may allah (swt) free the shackles of our brothers and sisters in the dungeouns of the infidels and tawaghut and reunite them with their families may allah (swt) send down his wrath upon all involved and punish these criminals your brother abuabdallah ------------------------------------------------------------- EUROPE'S SPECIAL INTERROGATIONS New Evidence of Torture Prison in Poland SOURCE: http://www.spiegel.de/international/...621450,00.html The current debate in the US on the "special interrogation methods" sanctioned by the Bush administration could soon reach Europe. It has long been clear that the CIA used the Szymany military airbase in Poland for extraordinary renditions. Now there is evidence of a secret prison nearby. Only a smattering of clouds dotted the sky over Szymany on March 7, 2003, and visibility was good. A light breeze blew from the southeast as a plane approached the small military airfield in northeastern Poland, and the temperature outside was 2 degrees Celsius (36 degrees Fahrenheit). At around 4:00 p.m., the Gulfstream N379P -- known among investigators as the "torture taxi" -- touched down on the landing strip. -

NO MORE EXCUSES WATCH a Roadmap to Justice for CIA Torture

HUMAN RIGHTS NO MORE EXCUSES WATCH A Roadmap to Justice for CIA Torture No More Excuses A Roadmap to Justice for CIA Torture Copyright © 2015 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-2996 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org NOVEMBER 2015 978-1-62313-2996 No More Excuses A Roadmap to Justice for CIA Torture Summary ........................................................................................................................................ 1 Methodology ................................................................................................................................. -

The Eastern European Islands of the Global GULAG

The Eastern European Islands of the Global GULAG By Nikolai Malishevski Theme: Law and Justice, Terrorism Global Research, December 11, 2013 Strategic Culture Foundation Among the first to report the existence of CIA special prisons and concentration camps in a number of countries, for example, in Poland, Romania,Lithuania , Ukraine, Bulgaria, Macedonia, and on the territory controlled by the Kosovar Albanian regime, were the Swiss media. In December 2005 the Polish newspaper Gazeta Wyborcza confirmed that the «main European secret CIA prison» is located in Poland. The scandal which was at that time hushed up has now resurfaced. In Strasbourg hearings have begun in the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) on a suit brought by two prisoners of the American Guantanamo Bay detention camp, Palestinians Al-Nashiri and Abu Zubaydah, who assert that in the early 2000s U.S. intelligence agencies detained them in a Polish military prison… For several months lawyers demanded that the court hearings be held behind closed doors and that the press not be admitted. However, the results of the investigation and the details of the abductions and tortures were made public anyway. It turned out that the Poles actively assisted in what the CIA calls «enhanced interrogation techniques», which include refined tortures and abuses like dehydration, hypothermia, and «putting the heat on» with death threats by putting a gun or a drill to someone’s head. That is how they interrogated prisoners in the secret CIA prison near the village of Stare Kiejkuty, 170 km from Warsaw. The Council of Europe accused Romania of creating secret prisons in 2007 (although they appeared there at least four years earlier). -

Rendition and the “Black Sites”

Chapter 5 Rendition and the “Black Sites” Between 2001 and 2006, the skies over Europe, Asia, Africa and the Middle East were crisscrossed by hundreds of flights whose exact purpose was a closely held secret. Sometimes the planes were able to use airports near major capitals, while on other occasions the mission required the pilots to land at out-of-the-way airstrips. The planes were being used by the CIA to shuttle human cargo across the continents, and the shadowy air traffic was the operational side of the U.S. government’s anti-terrorist program that came to be known as “extraordinary rendition.” After the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, the Bush administration resolved to use every available means to protect the United States from further attack. The extraordinary rendition program, used previously by President Bill Clinton, quickly became an important tool in that effort. In the years since, numerous investigations and inquiries have found evidence of illegal acts in the form of arbitrary detention and abuse resulting from the program. These, in turn, have led to strained relations between the United States and several friendly countries that assisted the CIA with the program. The program was conceived and operated on the assumption that it would remain secret. But that proved a vain expectation which should have been apparent to the government officials who conceived and ran it. It involved hundreds of operatives and the cooperation of many foreign governments and their officials, a poor formula for something intended to remain out of public view forever. Moreover, the prisoners transported to secret prisons for interrogations known as “black sites” would someday emerge.