Patricia Railing, Report: Malevich's Suprematist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Futurist Moment : Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture

MARJORIE PERLOFF Avant-Garde, Avant Guerre, and the Language of Rupture THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS CHICAGO AND LONDON FUTURIST Marjorie Perloff is professor of English and comparative literature at Stanford University. She is the author of many articles and books, including The Dance of the Intellect: Studies in the Poetry of the Pound Tradition and The Poetics of Indeterminacy: Rimbaud to Cage. Published with the assistance of the J. Paul Getty Trust Permission to quote from the following sources is gratefully acknowledged: Ezra Pound, Personae. Copyright 1926 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, Collected Early Poems. Copyright 1976 by the Trustees of the Ezra Pound Literary Property Trust. All rights reserved. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Ezra Pound, The Cantos of Ezra Pound. Copyright 1934, 1948, 1956 by Ezra Pound. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. Blaise Cendrars, Selected Writings. Copyright 1962, 1966 by Walter Albert. Used by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1986 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1986 Printed in the United States of America 95 94 93 92 91 90 89 88 87 86 54321 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Perloff, Marjorie. The futurist moment. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. Futurism. 2. Arts, Modern—20th century. I. Title. NX600.F8P46 1986 700'. 94 86-3147 ISBN 0-226-65731-0 For DAVID ANTIN CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Abbreviations xiii Preface xvii 1. -

Photo/Arts MY DEAR MALEVICH (MDM)

TOM R. CHAMBERS - Photo/Arts Highlights from his personal website. Many of the links on the page go back to the website for greater detailing. Tom R. Chambers is a documentary photographer and visual artist, and he is currently working with the pixel as Minimalist Art ("Pixelscapes") and Kazimir Malevich's "Black Square" ("Black Square Interpretations"). He has over 100 exhibitions to his credit. His "My Dear Malevich" project has received international acclaim, and it was shown as a part of the "Suprematism Infinity: Reflections, Interpretations, Explorations" exhibition in conjunction with the "100 Years of Suprematism" conference at Columbia University, New York City (2015). MY DEAR MALEVICH (MDM) "My Dear Malevich" This homage to Kazimir Malevich is a confirmation of Tom R. Chambers' Pixelscapes as Minimalist Art and in keeping with Malevich's Suprematism - the feeling of non-objectivity - the creation of a sense of bliss and wonder via abstraction. Chambers' action of looking within a portrait (photo) of Kazimir Malevich to find the basic component(s), pixel(s) is the same action as Malevich looking within himself - inside the objective world - for a pure feeling in creative art to find his "Black Square", "Black Cross" and other Suprematist works. And there's a mathematical parallel between Malevich's primitive square ("Black Square") ... divided into four, then divided into nine ("Black Cross") ... and Chambers' Pixelscapes. The pixel is the most basic component of any computer graphic, and it can be represented by 1 bit (a 1 if the pixel is black, or a 0 if the pixel is white). And filters (tools [e.g., halftone]) in a graphics program like Photoshop produce changes by mathematically modifying pixel values based on the values of neighboring pixels. -

C:\Users\Kai\Documents\CMU Teaching\Modern\Handouts

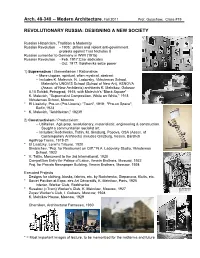

Arch. 48-340 -- Modern Architecture, Fall 2011 Prof. Gutschow, Class #19 REVOLUTIONARY RUSSIA: DESIGNING A NEW SOCIETY Russian Historicism, Tradition & Modernity Russian Revolution - 1905: strikes and violent anti-government protests against Tsar Nicholas II Russian surrender to Germany in WWI (1915) Russian Revolution - Feb. 1917:Czar abdicates - Oct. 1917: Bolsheviks seize power 1) Suprematism / Elementarism / Rationalism -- More utopian, spiritual, often mystical, abstract -- Includes K. Malevich, N. Ladovsky, Vkhutemas School, Malevich's UNOVIS School (School of New Art), ASNOVA (Assoc. of New Architects) architects K. Melnikov, Golosov 0.10 Exhibit, Petrograd, 1915, with Malevich’s “Black Square” K. Malevich, "Suprematist Composition, White on White," 1918 Vkhutemas School, Moscow * El Lissitzky, Pro-un (Pro-Unovis): "Town", 1919; "Pro-un Space", Berlin,1923 * K. Malevich, "Arkhitekton," 1923ff 2) Constructivism / Productivism: -- Utilitarian, Agit-prop, revolutionary, materialistic, engineering & construction. Sought a communitarian socialist art. -- Includes: Rodchenko, Tatlin, M. Ginsburg, Popova, OSA (Assoc. of Contemporary Architects) includes Ginzburg, Vesnin, Barshch AgitProp Trains, 1919-21 * El Lissitzky, Lenin's Tribune, 1920 Simbirchev, “Proj. for Restaurant on Cliff," N.A. Ladovsky Studio, Vkhutemas School, 1922 * V. Tatlin, Monument to the 3rd International, 1920 Competition Entry for Palace of Labor, Vesnin Brothers, Moscow, 1922 Proj. for Pravda Newspaper Building, Vesnin Brothers, Moscow, 1924 Executed Projects Designs for clothing, kiosks, fabrics, etc. by Rodchenko, Stepanova, Klutis, etc. * Soviet Pavilion at Expo. des Art Décoratifs, K. Melnikov, Paris, 1925 Interior, Worker Club, Rodchenko * Rusakov (=Tram) Worker's Club, K. Melnikov, Moscow, 1927 Zuyev Worker's Club, I. Golosov, Moscow, 1928 K. Melnikov House, Moscow, 1929 Chernikov, Architectural Fantasies, 1930 * = Most important images of lecture, to be memorized for the midterms and future . -

Read Book Kazimir Malevich

KAZIMIR MALEVICH PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Achim Borchardt-Hume | 264 pages | 21 Apr 2015 | TATE PUBLISHING | 9781849761468 | English | London, United Kingdom Kazimir Malevich PDF Book From the beginning of the s, modern art was falling out of favor with the new government of Joseph Stalin. Red Cavalry Riding. Articles from Britannica Encyclopedias for elementary and high school students. The movement did have a handful of supporters amongst the Russian avant garde but it was dwarfed by its sibling constructivism whose manifesto harmonized better with the ideological sentiments of the revolutionary communist government during the early days of Soviet Union. What's more, as the writers and abstract pundits were occupied with what constituted writing, Malevich came to be interested by the quest for workmanship's barest basics. Black Square. Woman Torso. The painting's quality has degraded considerably since it was drawn. Guggenheim —an early and passionate collector of the Russian avant-garde—was inspired by the same aesthetic ideals and spiritual quest that exemplified Malevich's art. Hidden categories: Articles with short description Short description matches Wikidata Use dmy dates from May All articles with unsourced statements Articles with unsourced statements from June Lyubov Popova - You might like Left Right. Harvard doctoral candidate Julia Bekman Chadaga writes: "In his later writings, Malevich defined the 'additional element' as the quality of any new visual environment bringing about a change in perception Retrieved 6 July A white cube decorated with a black square was placed on his tomb. It was one of the most radical improvements in dynamic workmanship. Landscape with a White House. -

Cubo-Futurism

Notes Cubo-Futurism Slap in theFace of Public Taste 1 . These two paragraphs are a caustic attack on the Symbolist movement in general, a frequent target of the Futurists, and on two of its representatives in particular: Konstantin Bal'mont (1867-1943), a poetwho enjoyed enormouspopu larityin Russia during thefirst decade of this century, was subsequentlyforgo tten, and died as an emigrein Paris;Valerii Briusov(18 73-1924), poetand scholar,leader of the Symbolist movement, editor of the Salles and literary editor of Russum Thought, who after the Revolution joined the Communist party and worked at Narkompros. 2. Leonid Andreev (1871-1919), a writer of short stories and a playwright, started in a realistic vein following Chekhov and Gorkii; later he displayed an interest in metaphysicsand a leaning toward Symbolism. He is at his bestin a few stories written in a realistic manner; his Symbolist works are pretentious and unconvincing. The use of the plural here implies that, in the Futurists' eyes, Andreev is just one of the numerousepigones. 3. Several disparate poets and prose writers are randomly assembled here, which stresses the radical positionof the signatories ofthis manifesto, who reject indiscriminately aU the literaturewritt en before them. The useof the plural, as in the previous paragraphs, is demeaning. Maksim Gorkii (pseud. of Aleksei Pesh kov, 1�1936), Aleksandr Kuprin (1870-1938), and Ivan Bunin (1870-1953) are writers of realist orientation, although there are substantial differences in their philosophical outlook, realistic style, and literary value. Bunin was the first Rus sianwriter to wina NobelPrize, in 1933.AJeksandr Biok (1880-1921)is possiblythe best, and certainlythe most popular, Symbolist poet. -

Digital Suprematism Overview

DIGITAL SUPREMATISM "Tom R. Chambers is a Texan with a “Russian, Suprematist soul”. He has repeatedly introduced the modern trend of new media art to the masses. He has brought Minimalism to the pixel. In 2000, Chambers began to look at the pixel in the context of Abstraction and Minimalism. And he is currently working with interpretations of Kazimir Malevich’s “Black Square” and other Suprematist forms. His work calls our attention to visual singularity, which is all that we see in the digital universe. Since the pixel corresponds to what we call “subatomic particles” in our physical universe, Chambers’ work connects us directly with the feeling of Russian Suprematism, described as the spirit that pervades everything, and pays tribute to the faith in the ability of abstraction to convey “net feeling in the work.” (Curator, OMG [One Month Gallery], Moscow, Russia, 2015) Chambers states: “I have always liked Minimalist works and as a digital artist, I began to explore the pixel as an art form in 2000. As I did research, and experimented with this picture element, I also began to read about Kazimir Malevich and his extreme Minimalist approach with ‘Black Square’. The more I contemplated his ‘Black Square’, the deeper I moved into the pixel and consequently the creation of the ‘My Dear Malevich’ project, which revealed similar to identical Suprematist forms that he created. I have focused on the pixel and his ‘Black Square’ ever since.” My Dear Malevich (MDM) (http://tomrchambers.com/malevich.html) In 2007, Chambers traveled (via magnification) into a digitized photograph of Malevich and discovered at the singular pixel level arrangements which echo back directly to Malevich's own totally abstract compositions. -

Art 150: Introduction to the Visual Arts David Mccarthy Rhodes College, Spring 2003 414 Clough, Ext

Art 150: Introduction to the Visual Arts David McCarthy Rhodes College, Spring 2003 414 Clough, Ext. 3663 417 Clough, MWF 11:30-12:30 Office Hours: MWF 2:00- 4:00, and by appointment. COURSE OBJECTIVES AND DESCRIPTION The objectives of the course are as follows: (1) to provide students with a comprehensive, theoretical introduction to the visual arts; (2) to develop skills of visual analysis; (3) to examine various media used by artists; (4) to introduce students to methods of interpretation; and (5) to develop skills in writing about art. Throughout the course we will keep in mind the following two statements: Pierre Auguste Renoir’s reminder that, “to practice an art, you must begin with the ABCs of that art;” and E.H. Gombrich’s insight that, “the form of representation cannot be divorced from its purpose and the requirements of the society in which the given language gains currency.” Among the themes and issues we will examine are the following: balance, shape and form, space, color, conventions, signs and symbols, representation, reception, and interpretation. To do this we will look at many different types of art produced in several historical epochs and conceived in a variety of media. Whenever possible we will examine original art objects. Art 150 is a foundation course that serves as an introduction for further work in studio art and art history. A three-hour course, Art 150 satisfies the fine arts requirement. Enrollment is limited to first- and second-year students who are not expected to have had any previous experience with either studio or art history. -

Primitivism in Russian Futurist Book Design 1910–14

Primitivism in Russian Futurist Book Design 1910–14 In the introduction to his book “Primitivism” in 20th ponents in 1913), Russian artists such as Mikhail Jared Ash Century Art, William Rubin notes the relative paucity of Larionov, Natalia Goncharova, Kazimir Malevich, and scholarly works devoted to “primitivism—the interest of Olga Rozanova espoused the fundamental aesthetic prin- modern artists in tribal art and culture, as revealed in ciples and theories, set the priorities, and developed the their thought and work.”1 While considerable attention courage to abandon naturalism in art in favor of free cre- has been paid to primitivism in early-twentieth-century ation, pure expression, and, ultimately, abstraction. French and German art in the time since Rubin’s 1984 The present work focuses on the illustrated publication, Western awareness of a parallel trend in book as the ideal framework in which to examine primi- Russia remains relatively limited to scholars and special- tivism in Russia. Through this medium, artists and writ- ists. Yet, the primary characteristics that Russian artists’ ers of the emerging avant-garde achieved one of the recognized and revered in primitive art forms played as most original responses to, and modern adaptations of, profound a role in shaping the path of modern art and primitivism, and realized the primary goals and aesthetic literature in Russia as they did in the artistic expressions credos set forth in their statements and group mani- of Western Europe. “Primitive” and “primitivism,” as festos. These artists drew on a wide range of primitive they are used in this text, are defined as art or an art art forms from their own country: Old Russian illumin- style that reveals a primacy and purity of expression. -

Kazimir Malevich Was a Russian Artist of Ukrainian Birth, Whose Career Coincided with the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and Its Social and Cultural Aftermath

QUICK VIEW: Synopsis Kazimir Malevich was a Russian artist of Ukrainian birth, whose career coincided with the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 and its social and cultural aftermath. Malevich was the founder of the artistic and philosophical school of Suprematism, and his ideas about forms and meaning in art would eventually form the theoretical underpinnings of non- objective, or abstract, art making. Malevich worked in a variety of styles, but his most important and famous works concentrated on the exploration of pure geometric forms (squares, triangles, and circles) and their relationships to each other and within the pictorial space. Because of his contacts in the West, Malevich was able to transmit his ideas about painting to his fellow artists in Europe and the U.S., thus profoundly influencing the evolution of non-representational art in both the Eastern and Western traditions. Key Ideas • Malevich worked in a variety of styles, from Impressionism to Cubo-Futurism, arriving eventually at Suprematism - his own unique philosophy of painting and art perception. • Malevich was a prolific writer. His treatises on philosophy of art address a broad spectrum of theoretical problems and laid the conceptual basis for non-objective art both in Europe and the United States. • Malevich conceived of an independent comprehensive abstract art practice before its definitive emergence in the United States. His stress on the independence of geometric form influenced many generations of abstract artists in the West, especially Ad Reinhardt. © The Art Story Foundation – All rights Reserved For more movements, artists and ideas on Modern Art visit www.TheArtStory.org DETAILED VIEW: Childhood Malevich was born in Ukraine to parents of Polish origin, who moved continuously within the Russian Empire in search of work. -

Challenging Tradition

CHALLENGING TRADITION: BAUHAUS, DE STIJL, and RUSSIAN CONSTRUCTIVISM (Kandinsky, Mondrian, Breuer, Tatlin, and Stepanova) WASSILY KANDINSKY Online Links: Wassily Kandinsky - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Der Blaue Reiter - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Quotes from Wassily Kandinsky http://www.smarthistory.org/Kandinsky-CompositionVII.html Theosophy - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Arnold Schoenberg - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Helen Mirren on Kandinsky – YouTube Kandinsky Drawing 1926 – YouTube Schonberg and Kandinsky - YouTube FRANZ MARC Online Links: Franz Marc - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Meditation on Blue Horses by Franz Marc - YouTube PIET MONDRIAN Online Links: Piet Mondrian - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia De Stijl - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia http://www.smarthistory.org/de-stijl- mondrian.html Gerrit Rietveld - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Theo van Doesburg - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Bauhaus Online Links: Accommodation inside the Studio Building at Bauhaus Bauhaus - Unesco Site Bauhaus – Wikipedia Bauhaus: Design in a Nutshell Architecture - Dessau Bauhaus - YouTube KAZIMIR MALEVICH Online Links: Kazimir Malevich - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Suprematism - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Tabula rasa - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Plays: Victory over the Sun, Introduction and Costume Design Victory over the Sun - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Malevich's White on White compared with Monet - Smarthistory VLADIMIR TATLIN and the RUSSIAN CONSTRUCTIVISTS Online Links: Vladimir Tatlin - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Constructivism (art) - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Tatlin's Tower - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Naum Gabo - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Stepanova's Results from the First Five Year Plan Rodchenko - Spatial Construction No. 12 (with video) – MOMA Rodchenko's Lines of Force - Tate Modern Vassily Kandinsky. Picture with an Archer, 1909 The Russian artist Vassily Kandinsky (1866-1944) was among the first to eliminate recognizable objects from his paintings. -

"Bitter Harvest: Russian and Ukrainian Avant-Garde 1890-1934"

BITTER HARVEST BITTER RUSSIAN AND UKRAINIAN AVANT-GARDE 1890-1934 AND UKRAINIAN AVANT-GARDE RUSSIAN BITTER HARVEST: RUSSIAN AND UKRAINIAN AVANT-GARDE 1900-1934 JAMES BUTTERWICK 2 3 Front cover: Alexander Bogomazov Portrait of the Artist’s Daughter, Yaroslava (detail), 1928 Inside cover: Alexander Archipenko Still Life (detail), c. 1918 RUSSIAN AND UKRAINIAN AVANT-GARDE 1890-1934 First published in 2017 by James Butterwick WWW.JAMESBUTTERWICK.COM All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise, without first seeking the permission of the copyright owners and the publishers. All images in this catalogue are protected by copyright and should not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Details of the copyright holder to be obtained from James Butterwick. © 2017 James Butterwick Director: Natasha Butterwick Editorial Consultant: Simon Hewitt Stand: Isidora Kuzmanovic 34 Ravenscourt Road, London W6 OUG Catalogue: Katya Belyaeva Tel +44 (0)20 8748 7320 Email [email protected] Design and production by Footprint Innovations Ltd www.jamesbutterwick.com 4 SOME SAW NEW YORK James Butterwick On 24 February 1917, a little over one hundred years ago, Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes completed their second and final tour of the United States. The first, from January to April 1916, took in 17 cities and began at the long-defunct Century Theater and ended at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. Two of the leading lights of the Russian Avant-Garde, Mikhail Larionov and Natalia Goncharova, had been working for the Ballets Russes since 1915, when Larionov had made the colorful costume design or a Young Jester in the ballet Soleil du Nuit, featured in this catalogue. -

Following the Black Square: the Cosmic, the Nostalgic & the Transformative in Russian Avant-Garde Museology Teofila Cruz-Uri

Following The Black Square: The Cosmic, The Nostalgic & The Transformative In Russian Avant-Garde Museology Teofila Cruz-Uribe A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in International Studies: Russia, East Europe and Central Asia University of Washington 2017 Committee: Glennys Young James West José Alaniz Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Jackson School of International Studies Cruz-Uribe ©Copyright 2017 Teofila Cruz-Uribe 1 Cruz-Uribe University of Washington Abstract Following The Black Square: The Cosmic, The Nostalgic & The Transformative In Russian Avant-Garde Museology Teofila Cruz-Uribe Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Jon Bridgman Endowed Professor Glennys Young History Department & Jackson School of International Studies Contemporary Russian art and museology is experiencing a revival of interest in the pioneering museology of the Russian artistic and political avant-garde of the early 20th century. This revival is exemplified in the work of contemporary Russian conceptual artist and self-styled ‘avant-garde museologist’ Arseniy Zhilyaev (b. 1984). Influential early 20th century Russian avant-garde artist and museologist Kazimir Malevich acts as the ‘tether’ binding the museologies of the past and present together, his famous “Black Square” a recurring visual and metaphoric indicator of the inspiration that contemporary Russian avant-garde museology and art is taking from its predecessors. This thesis analyzes Zhilyaev’s artistic and museological philosophy and work and determines how and where they are informed by Bolshevik-era avant-garde museology. This thesis also asks why such inspirations and influences are being felt and harnessed at this particular juncture in post-Soviet culture.