Table of Contents Scope ...1 Background

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Codebook for 389696727Guyana Lapop Americasbarometer 2012 Rev1 W

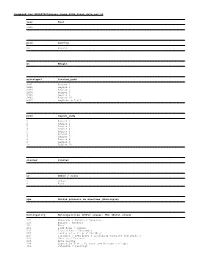

Codebook for 389696727guyana lapop americasbarometer 2012 rev1_w pais Country -- All data are copyrighted by the Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP) and may only be used with the explicit written permission of LAPOP, normally via a license or repository agreement (see our web page for instructions, www.LapopSurveys.org). Data sets may never be disseminated to third parties. -- All data are deidentified and regulated by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Vanderbilt University. They may be used only by those who have fulfilled all IRB requirements. -- For more information and details about the sample design, please consult the technical and country reports through a link on the LAPOP website: www.AmericasBarometer.org. 24 Guyana year Year 2012 idnum Questionnaire number [assigned at the office]. Interview number estratopri Stratum_code 2401 Greater Georgetown 2402 Region 3 and rest of region 4 2403 Regions 2,5,6 2404 Regions 1,7,8,9,10 estratosec Size of the Municipality 1 Large (Urban areas) 2 Medium (Rural areas with more than 5,000) 3 Small (Rural areas with fewer than 5,000) upm Primary Sampling Unit prov Regions municipio County (Urban areas) 104 Waini 202 Riverstown / Annandale 205 Charity / Urasara 206 Anna Regina 301 Patentia / Toevlugt 302 Canals Polder 305 Klein Pouderoyen / Best 307 Blankenburg / Hague 309 Uitvlugt / Tuschen 314 Wakenaam ( Essequibo Islands ) 315 Amsterdam (Demerara River) / Vriesland 317 Sparta / Bonasika and Rest of Essequibo Islands 402 Vereeniging / Unity 403 Grove / Haslington 405 Foulis / Buxton 406 La Reconnaissance / Mon Repos 408 La Bonne Intention / Better Hope 409 Plaisance / Industry 411 Mocha / Arcadia 413 Diamond / Golden Grove 414 Good Success / Caledonia 416 City of Georgetown 417 Suburbs of Georgetown 418 Soesdyke-Linden highway (including Timehri) 502 Rosignol / Zeelust 503 Bel Air / Woodlands 504 Woodley Park / Bath 505 Naarstigheid / Union 602 No.74 Village / No.52 Village 608 Whim / Bloomfield 609 John / Port Mourant 611 Fyrish / Gibraltar 613 No. -

41 1994 Guyana R01634

Date Printed: 11/03/2008 JTS Box Number: IFES 4 Tab Number: 41 Document Title: Guyana Election Technical Assessment Report: 1994 Local Government and Document Date: 1994 Document Country: Guyana IFES ID: R01634 I I I I GUYANA I Election Technical Assessment I Report I 1994 I LocalIMunicipal Elections I I I I I I I I I r I~) ·Jr~NTERNATIONAL FOUNDATION FOR ELECTORAL SYSTEMS ,. I •,:r ;< .'' I Table of Contents I GUYANA LOCAL GOVERNMENT AND MUNICIPAL ELECTIONS 1994 I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 I. Background 3 I A. Local Government and Municipal Elections 3 B. Guyana Elections Commission 4 C. National Registration Centre 5 I D. Previous IFES Assistance 6 II. Project Assistance 7 A. Administrative and Managerial 7 I B. Technical 8 III. Commodity and Communications Support 9 A. Commodities 9 I B. Communications II IV. Poll Worker Training 13 I A. Background 13 B. Project Design 14 C. Project Implementation 14 I D. Review of Project Objectives 15 VI. Voter and Civic Education 17 I' A. Background I7 B. Project Design 18 C. Project Implementation 19 D. Media Guidelines for Campaign Coverage 22 I E. General Observations 23 F. Review of Project Objectives 24 I VI. Assistance in Tabulation of Election Results 25 A. Background 25 B. Development of Computer Model 26 1 C. Tabulation of Election Results 27 VII. Analysis of Effectiveness of Project 27 A. Project Assistance 27 I B. Commodity and Communications Support 28 C. Poll Worker Training 28 D. Voter and Civic Education 29 I E. Assistance in Tabulation of Election Results 29 VIII. -

Ser. Lastname Firstname Middlename Address 1 AARON TIMERA SILICIA 67 BUS SHED STREET NO. 2 SCHEME UITVLUGT WEST COAST DEMERARA 2

PARIKA REGISTRATION OFFICE Ser. LastName FirstName MiddleName Address 1 AARON TIMERA SILICIA 67 BUS SHED STREET NO. 2 SCHEME UITVLUGT WEST COAST DEMERARA 2 ABDOOL MOHAMED AZEEZ 337 NORTH NEW SCHEME ZEELUGT EAST BANK ESSEQUIBO 3 ABDULLA PAULINE 194 SIXTH STREET WEST HOUSING SCHEME MET-EN-MEERZORG WEST COAST DEMERARA 4 ABDU-RAHMAN ABDULLAH JINNAH N PUBLIC ROAD LE DESTIN EAST BANK ESSEQUIBO 5 ABRAHIM BIBI WAHEEDA 24 BACK STREET KASTEV MET-EN-MEERZORG WEST COAST DEMERARA 6 ABRAHIM MOHAMED AZIM 32 SECOND STREET OLD SCHEME TUSCHEN EAST BANK ESSEQUIBO 7 ABRAHIM ZULAIKA KHATUN 32 SECOND STREET OLD SCHEME TUSCHEN EAST BANK ESSEQUIBO 8 ADAMS-LAURENT ONEKA ABIOLLA 31 ZEELANDIA WAKENAAM 9 ADNARAIN MANURAJ 4 DEVIL DAM PHILADELPHIA EAST BANK ESSEQUIBO 10 AGNES 145 PUBLIC ROAD SOUTH ZEEBURG WEST COAST DEMERARA 11 ALBERTS WAYNE IGANTUS BARAMA LANDING BUCKHALL ESSEQUIBO RIVER 12 ALFRED ESHA 208 SOUTH NEW SCHEME ZEELUGT EAST BANK ESSEQUIBO 13 ALFRED RAMDAI 70 PREM NAGAR MET-EN-MEERZORG WEST COAST DEMERARA 14 ALGURAM CHANDRAWATTIE 78 PREM NAGAR MET-EN-MEERZORG WEST COAST DEMERARA 15 ALGURAM NAOMI SIMONE 18 SECOND STREET NORTH HOUSING SCHEME DE WILLEM WEST COAST DEMERARA 16 ALGURAM RAMGOBIN 18 SECOND STREET NORT HOUSING SCHEME DE WILLEM WEST COAST DEMERARA 17 ALGURAM SASENARINE 78 PREM NAGAR MET-EN-MEERZORG WEST COAST DEMERARA 18 ALI BADORA HABIBAN 246 AREA G DE WILLEM WEST COAST DEMERARA 19 ALI BIBI NAZMOON 18 PUBLIC ROAD EAST HOUSING SCHEME MET-EN-MEERZORG WEST COAST DEMERARA 20 ALI EJAZ 18 PUBLIC ROAD EAST HOUSING SCHEME MET-EN-MEERZORG WEST COAST DEMERARA -

Guyana's Flood Disaster...The National Response

Introduction The natural disaster…and after Torrential rain, a deluge, an inundation of parts of the Coastland, in short - the country’s worst natural disaster, was the experience of Guyanese during the January- February period. The average amount of rainfall in Guyana for the month of January for the past 100 years is 7.3 inches. However, the country witnessed more than seven times that in January 2005 - some 52 inches. From December 24 through January 31 the total amount of rainfall exceeded 60 inches, with one night’s rainfall amounting to seven inches. This resulted in severe flooding and Government declaring Regions Three, Four and Five disaster areas. As the Administration planned its response, President Bharrat Jagdeo immediately called meetings of Cabinet Ministers, Leader of the Opposition Robert Corbin, Joint Service Heads and the City Council. Later he met with representatives of the Guyana Red Cross and members of religious organizations and non-governmental organizations. From these meetings with various stakeholders, committees, including members of the Opposition, were established in charge of water, food, shelter, health care and infrastructure, to assist affected people. Cabinet Ministers were dispatched to affected areas and provided periodic briefs to the Head of State. A committee headed by Cabinet Secretary Dr. Roger Luncheon to coordinate assistance from overseas and the donor community, was also established. A Joint Operation Centre (JOC) was set up at Eve Leary and the relief efforts were coordinated through this entity, while the President’s Residence, State House was used as a resource centre. The worst hit areas were the East Coast of Demerara in Region Four and Canal No. -

Tariff Consolidation

----------------------------------------------- ----------------------------------------------- ----------------------------------------------- ----------------------------------------------- ----------------------------------------------- -----------------------------------------------Public Utilities Commission ----------------------------------------------- -----------------------------------------------Annual Report 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chairman’s Statement 3 Introduction 5 Organisational Chart 8 REPORTS Complaints Divisions 13 Engineering Division 26 Finance Division 29 Accountant’s Review 41 2 FROM THE DESK OF THE CHAIRMAN Justice Prem Persaud CCH (ret’d) Regulation performs a vital role in the operation of public utilities which provide essential and vital services to consumers, and here in Guyana the Public Utilities Commission has been given the role as the watch-dog, and to hold an even keel between the consumers and the utility Companies. I have been intimately associated with Regulated bodies within the Caribbean in my capacity as a member/official of OOCUR, (ORGANISATION OF CARIBBEAN UTILITY REULATORS)—and regret to note that in the region, Governments have encountered problems with their approach to Utility Regulators. There are cases where bad relationships exist between the Regulators and Utility Companies, and in these small and fragile open economies there are always implications for social, economic and political developments within these countries. These elements sometimes influence regulatory practices and in most -

Sketch Map of the Good Hope-Pomona Neighbo Urhood

PROPOSED DESCRIPTION AND DEMARCATION OF CONSTITUENCIES FOR LOCAL GOVERNMENT ELECTIONS 2010 Prepared by Operations Department 9th March, 2010 1 DISTRICT NO. 1 (BARIMA / WAINI) REGISTRATION AREA: SUB – REGION 1 LOCAL AUTHORITY AREA: MABARUMA/KUMAKA/HOSORORO NO. OF CONSTITUENCIES: 6 1ST CONSTITUENCY: THOMAS HILL-SMITH CREEK DIVISION/SUB DIVISION: 112192 A & 112192 B (PART OF) DESCRIPTION OF CONSTITUENCY: THIS CONSTITUENCY EXTENDS FROM THE BARIMA RIVER AT THE VENEZUELA AND GUYANA BORDER ALONG THE BARIMA RIVER TO THE MABARUMA ROAD AT ITS NORTHERN EXTREMITY THEN ALONG THE WHITE CREEK ROAD THEN ALONG THE COMMON BOUNDARY BETWEEN THOMAS HILL AND BARABINA HILL TO THE MURURUMA RIVER AT ITS SOUTHERN EXTREMITY TO AN IMAGINARY EAST WEST LINE APPROXIMATELY 5 KM TO THE WHITE CREEK BRIDGE AT ITS EASTERN EXTREMITY THEN ALONG THE RIGHT BANK OF THE MURURUMA RIVER TO THE BARIMA RIVER AT ITS WESTERN EXTREMITY. 2ND CONSTITUENCY: MABARUMA SETTLEMENT/BARIMANOBO DIVISION/SUB DIVISION: 112192 B (PART OF) DESCRIPTION OF CONSTITUENCY: THIS CONSTITUENCY EXTENDS FROM THE JUNCTION OF THE MABARUMA ROAD AND THE BARIMA RIVER ALONG THE LEFT BANK OF THE BARIMA RIVER AT ITS NORTHERN EXTREMITY THEN ALONG THE LEFT BANK OF THE ARUKA RIVER TO THE MOUTH OF THE ATTIBANI CREEK AT ITS SOUTHERN AND EASTERN EXTREMITIES THEN ALONG THE ATTIBANI CREEK TO THE JUNCTION OF THE MABARUMA ROAD AND BARIMA RIVER AT ITS WESTERN EXTREMITY. 2 3RD CONSTITUENCY: MABARUMA TOWNSHIP -MABARUMA COMPOUND-BROOMES ESTATE DIVISION/SUB DIVISION: 112192 B (PART OF) DESCRIPTION OF CONSTITUENCY: THIS CONSTITUENCY EXTENDS FROM THE COMMON BOUNDARY BETWEEN THOMAS HILL AND BARABINA HILL ALONG THE COMMON BOUNDARY BETWEEN MABARUMA TOWNSHIP AND THOMAS HILL TO THE WHITE CREEK BRIDGE AT ITS NORTHERN EXTREMITY THEN ALONG THE KUMAKA CREEK TO BARABINA HILL AT ITS SOUTHERN EXTREMITY THEN ALONG THE BUILDING CREEK THEN ALONG THE ATTIBANI CREEK AT ITS EASTERN EXTREMITY THEN ALONG THE VALLEY BETWEEN THE MABARUMA COMPOUND/TOWNSHIP AND BARABINA HILL AT ITS WESTERN EXTREMITY. -

St. STANISLAUS MAGAZINE

A.M.D.G. St. STANISLAUS MAGAZINE ASSOCIATION SECTION VOL. [2] October 1944 No. [2] Editor: W.E.V. Harrison, B.A (Lond.) Assistant Editor: A. A. Abraham, Jnr. Business Manager: J. Fernandes Adviser: C.N. Delph CONTENTS ASSOCIATION SECTION Frontispiece (St. Stanislaus Kostka) List of Old Boys Serving with the Forces St. Stanislaus College Association A Week-end Trip around Part of British Committee of Management Guiana Editorial The Team and You Literary and Debating Group The Dim Past Monthly Programmes Children of Today, Citizens of Tomorrow Acknowledgement Travels of a Tenderfoot Roll of Honour Education St. Stanislaus College Association St. Stanislaus College Association Scholarship - Enrolment Form COLLEGE SECTION ST. STANISLAUS COLLEGE ASSOCIATION 1944 St. Stanislaus Kostka COMMITTEE OF MANAGEMENT: President: C. P. De FREITAS. Vice-Presidents: C. N. DELPH & C. C. De FREITAS. Hony. Secretary: W.E.V. HARRISON. Hony. Treasurer: W. RODRIGUES. Hony. Asst. Secretary: JOHN FERNANDES Members: JORGE JARDIM A. A. ABRAHAM, Jnr. J. B. GONSALVES C. F. De CAIRES F. I. De CAIRES H. W. De FREITAS. Ex-officio Members of Committee: REV. Fr. F. J. SMITH, S.J., B.A. (Principal, St. Stanislaus College). REV. Fr. A. GILL, S.J. (Games Master, St. Stanislaus College). Top EDITORIAL On the third Friday of each month, there takes place at the College an evening's entertainment of some sort or other – a lecture perhaps, or a talk illustrated by lantern slides, sometimes a social. The Literary and Debating Group arranges monthly debates or "quizzes". The 10th of November is fixed, as the day on which the Association's second annual dinner will be held. -

Commissioner of Local Go¥Ernment

► • . ·.. lrttt.11� C6utaua. ANNUAL REPORT OP 111B COMMISSIONER OF LOCAL GO¥ERNMENT FOR THE YEAR 1962. (Ptlnled b, the Authority of His Excellency the Govemor.) GEORGETOWN, DEMERARA. BRITISH GUIANA. 1963. c.a.P. & s. 1422/63. DEPARTMENT OF LOCAL GOVERNMENT, Lot 6, Brickdam, Georgetown, BRITISH GUIANA. 25th June, 1963. Sir, ••••• I have the honour to submit the attached report on the work of the Department of Local Government for the year 1962. I have the honour to be, Sir, Your obedient servant, ' J<L--.,( � Acting ��er of Local Government. The Honourable, The Minister of Home Affairs, CONTENTS PART I - LOCAL GOVERNMENT Staff ••• ... 1 Organisation & Methods ••• ... 2 Courses ••• 3 Boards and Committees ••• 3 Municipal Administration - Georgetown New Amsterdam ••• ••. 4 Town Council Elections ••• • •• 6 Georgetown Sewerage and Water Commissioners 6 Administration of th e Coastlands ••• 7 Village Administration ••• . •• 7 Postponement of Village Elections •.• 12 Local Authorities - Finance •.. ... 13 Arrears Rates ••• ... 15 Proceedings by Parate Execution ... 17 Order on Collector of Rates 17 Loans and Grants to Local Authorities 17 Short-ferm Advances to Local Authorities 19 Grant towards Administrative Expenses 20 Reserve Funds ••• • •• 21 Inspection of Books and Accounts •.• 21 Local Authorities Guarantee Fund ••• 22 Pensions and- Gratuities to Officers and Servants of Local Authorities ••• 23 Revision of Salaries of Overseers and Other employees of Local .\uthorities 23 Inspection ·of Scales, Weights and Measures 24 Drainage and Irrigation -

Guyana Technology Action Plan for Mitigation

Government of the Cooperative Republic of Guyana Technology Action Plan for Mitigation January 2018 Supported by: Guyana Technology Action Plan for Mitigation January 2018 Copyright © 2018 Office of Climate Change, Ministry of the Presidency, Guyana and UNEP-DTU. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder, provided that the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. This publication is an output of the Technology Needs Assessment project, funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and implemented by UN Environment (UNEP) and the UNEP DTU Partnership (UDP) in collaboration with the Regional Centres (Libélula, Peru and Fondación Bariloche (FB), Argentina). The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of UDP, UN Environment, Libélula, FB or the Government of Guyana. We regret any errors or omissions that may have been unwittingly made. 1 Acknowledgements The Government of the Cooperative Republic of Guyana is extremely grateful for the contributions made by the National TNA Committee, local experts, stakeholders from the various sectors, the Consultant, Mr. Shyam Nokta, and the staff of the Office of Climate Change, Ministry of the Presidency in preparing Guyana’s TNA mitigation reports and this technology action plan on mitigation and accompanying project idea notes. We are also grateful for the support provided by the Global Environment Facility, United Nations Environment Programme – Technical University of Denmark (UNEP-DTU) Partnership, and the TNA Regional Offices for the Latin American and Caribbean Region Fundación Bariloche and Libélula. -

Geographical Constituency Lists

NOTICE Given Under THE REPRESENTATION OF THE PEOPLE ACT (Cap. 1:03) GENERAL ELECTION GEOGRAPHICAL CONSTITUENCY APPROVED LISTS OF CANDIDATES TITLE OF LIST: A NEW UNITED GUYANA (A.N.U.G) SYMBOL OF LIST: CELLULAR PHONE TYPE OF LIST: GEOGRAPHICAL CONSTITUENCY REGION No. 2 No. NAME ADDRESS OCCUPATION 135CC THIRD AVENUE ECCLES EAST BANK 1 ARJUNE, MOHENDRA LEGAL OFFICER DEMERARA CAMACHO, BRUCE 190 LANCE GIBBS STREET QUEENSTOWN 2 - ASHTON GEORGETOWN DE ABREU, AZAD 445 FORDYCE STREET REPUBLIC PARK PETER'S JEWELLER 3 LIONEL DEMETRIUS HALL EAST BANK DEMERARA 2170 SECTION C BLOCK X DIAMOND EAST BANK 4 SUKH, BHAVITA DEVI - DEMERARA TITLE OF LIST: A NEW UNITED GUYANA (A.N.U.G) SYMBOL OF LIST: CELLULAR PHONE TYPE OF LIST: GEOGRAPHICAL CONSTITUENCY REGION No. 3 No. NAME ADDRESS OCCUPATION 1 CORREIA, MARY ANN 13-14 FRIENDSHIP EAST BANK DEMERARA - GOMES, TRISTAN 54 EASTERN HIGHWAY LAMAHA GARDENS 2 ARCHITECT WENDELL GEORGETOWN GORDON, KEVON 125 BLOCK 22 ONE MILE LINDEN UPP. DEM. RIV. - 3 NORMA ASHANNA 4 HARINARAIN, ARJUNE 172 SECTION C TURKEYEN GEORGETOWN DOCTOR SINGH, LAURA 191 DUNCAN STREET, LAMAHA GARDENS, - 5 THERESA GEORGETOWN NORVILLE, SESE 137 EAST SIDELINE DAM, STEWARTVILLE, WEST 6 ENGINEER RAFAEL COAST DEMERARA TITLE OF LIST: A NEW UNITED GUYANA (A.N.U.G) SYMBOL OF LIST: CELLULAR PHONE TYPE OF LIST: GEOGRAPHICAL CONSTITUENCY REGION No. 4 No. NAME ADDRESS OCCUPATION JACOBUS, 61 SUSSEX STREET ALBOUYSTOWN GEORGETOWN - 1 MICHELANGELO LAM, CANDACE E5 HADFIELD STREET WORTMANVILLE 2 - THERESA GEORGETOWN LAWRENCE, MARITZA 30 SURAT DRIVE TRIUMPH EAST COAST -

Source: Adapted from Gazetteer of Guyana, Published by Lands and Surveys Department and the German Agency for Technical Cooperation, Georgetown, 2001)

PLACE NAMES ALONG GUYANA’S ROADS (Source: Adapted from Gazetteer of Guyana, published by Lands and Surveys Department and the German Agency for Technical Cooperation, Georgetown, 2001) 1. ESSEQUIBO COAST ROAD Northwards from Supenaam River Place Name Kilometres Miles Supenaam River 0 0 Good Hope 1 0.6 Spring Garden 2.5 1.6 Good Intent 3.5 2.2 Aurora 4 2.5 Makeshift 5.5 3.4 Warousi 6 3.7 Three Friends 6.5 4 Dryshore 6.6 4 Hibernia 7 4.4 Fairfield 8 5 Vilvoorden 9 5.6 Middlesex 10 6.2 Huis T’Dieren 10.5 6.5 Pomona 11.5 7.1 Ituribisi River 12 7.5 Riverstown 12.5 7.8 Adventure 14.5 9 Onderneeming 16.5 10.3 Belfield 18 11.2 Maria’s Lodge 18 11.2 Johanna Cecelia 19 11.8 Zorg 20 12.4 Golden Fleece 21 13 Perserverance 22 13.7 Wastelands 22.5 14 Bremen 23 14.3 Cullen 23.5 14.6 Unu River 24 14.9 Abram’s Zuil 24 14.9 Annandale 24 15.5 Zorg en Vlygt 25.5 15.8 Hoff van Aurich 26 16.2 L’Union 27 16.8 Degeraad 27.5 17.1 Queenstown 28 17.4 1 Mocha 28 17.4 Westfield 28.5 17.7 Alliance 29 18 Taymouth Manor 29.5 18.3 Affiance 30.5 18.9 Columbia 31 19.3 Aberdeen 31.5 19.6 Three Friends 32 19.9 Land of Plenty 32.5 20.2 Mainstay 33 20.5 Reliance 34 21.1 Bush Lot 34.5 21.4 Anna Regina 35.5 22.1 Henrietta 36.5 22.7 Richmond 37 23 La Belle Alliance 38 23.6 Lima 38.5 23.9 Coffee Grove 39.5 24.5 Danielstown 40 24.8 Fear Not 40 24.8 Sparta 40.5 25.2 Cape Batave 41 25.5 Windsor Castle 41 25.5 Hampton Court 42 26.1 Devonshire Castle 43.5 27 Walton Hall 44.5 27.6 Paradise 45 28 The Jib 46 28.6 Exmouth 46.5 28.9 Eliza 47 29.2 Dunkeld and Perth 48 29.8 Dartmouth 48.5 30.1 Westbury 49.5 30.7 Bounty Hall 50 31 Phillips 50.5 31.4 Chandler 51.5 32 Better Success 51.5 32 Andrews 51.5 32 Better Hope 52.5 32.6 La Resource 54 33.5 Maria’s Delight 55 34.2 Opposite 55.5 34.5 Evergreen 56.5 35.1 Somerset - Berks Canal 57 35.4 Berks 57 35.4 2 Somerset 57.5 35.7 Amazon 61 37.9 Charity 61 37.9 Charity Jetty 61.5 38.2 Pomeroon River 61.5 38.2 2. -

Codebook for 996997807Guyana Lapop 2008 Final Data Set V3

Codebook for 996997807guyana_lapop_2008_final_data_set_v3 year Year 2009 pais Country 24 Guyana wt Weight estratopri Stratum_code 2401 Region 2 2402 Region 3 2403 Region 4 2404 Region 5 2405 Region 6 2406 Region 10 2407 Regions 1,7,8,9 prov region_code 1 Region 1 2 Region 2 3 Region 3 4 Region 4 5 Region 5 6 Region 6 7 Region 7 8 Region 8 9 Region 9 10 Region 10 cluster Cluster ur Urban / rural 1 Urban 2 Rural upm Unidad primaria de muestreo (Municipio) municipality Municipalities (Urban areas); NDC (Rural areas) 101 Mabaruma / Kumaka / Hosororo 103 Barima / Amakura 104 Waini 201 Good Hope / Pomona 202 Riverstown / Annandale 203 Zorg - En - Vlygt / Aberdeen 204 Paradise / Evergreen ( Including Somerset and Berks ) 205 Charity / Urasara 206 Anna Regina 299 Supernaam River, Bethany and Mashabo villages 301 Patentia / Toevlugt 302 Canals Polder 303 Nismes / La Grange 304 Meer Zorgen / Malgre Tout 305 Klein Pouderoyen / Best 306 Nouvelle Flanders / La Jalousie 307 Blankenburg / Hague 308 Cornelia Ida / Stewartville 309 Uitvlugt / Tuschen 312 Parika / Mora 403 Grove / Haslington 405 Foulis / Buxton 406 La Reconnaissance / Mon Repos 408 La Bonne Intention / Better Hope 409 Plaisance / Industry 410 Eccles / Ramsburg 411 Mocha / Arcadia 412 Herstelling / Little Diamond 413 Diamond / Golden Grove 414 Good Success / Caledonia 415 Te Huist Coverden / Soesdyke 416 Georgetown 417 Suburbs of Georgetown 501 Gelderland / No 3 502 Rosignol / Zeelust 504 Woodley Park / Bath 505 Naarstigheid / Union 506 Tempe / Seafield 507 Rising Sun / Profit 508 Abary / Mahaicony 509 Chance / Hamlet 510 Farm / Woodlands 599 Rest of Region 5 601 Jackson Creek / Crabwood creek 602 No.74 Village / No.52 Village 604 Joppa / Macedonia 608 Whim / Bloomfield 610 Hampshire / Kilcoy 611 Fyrish / Gibraltar 613 No.