Learning Together

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rowena Soriaga Discussed ESSC's Key Findings in the 2005-2018 Land

Interpreting the 2005-2018 Land Cover Change Figures of Bukidnon ALARM-GAUP Analysis Team (ER2) Rowena Soriaga, PES/REDD+ Adviser Kumiko Shimamoto-Kubo, Forest Carbon Specialist Pedro Walpole SJ, Social Impacts Adviser Presentation Outline ❖ Context ❖ Analysis Method ❖ Key Findings ❖ Recommendations Context Philippine National REDD-Plus Strategy (PNRPS) identified the primary driver of deforestation and forest degradation as: “uncertainty regarding the exact drivers and sites of deforestation and forest degradation, which limits ability to develop targeted and effective conservation interventions” How can we manage a resource if we don’t know… …where it is? (location) …how much of it exists? (quantification) …what causes changes? (drivers, - and +) B A S E L I N E 0 U P D A T E L O C A T I O N QUANTIFICATION Tree cover stock change between 2005 & 2018 Bukidnon Bukidnon LC 2005 LC 2018 Difference % GAIN/LOSS Land Cover Land Cover percentage percentage between of the LAND COVER (LC) 2005 2018 of the Total of the Total 2018 and Difference Area (ha) Area (ha) land area land area 2005 (Ha) over 2005 NATURAL FOREST 225,961 213,066 25% 24% -12,896 -6% Mossy forest 129,135 109,353 14% 12% -19,782 -15% Primary 25,338 15,149 3% 2% -10,188 -40% Secondary 71,488 88,563 8% 10% 17,075 24% PLANTATION FOREST 7,768 5,333 1% 1% -2,435 -31% Plantation trees 6,200 4,422 1% 0% -1,778 -29% Pine Plantation 1,568 910 0% 0% -658 -42% Other cover stock change between 2005 & 2018 Bukidnon Bukidnon LC 2005 LC 2018 Difference % GAIN/LOSS Land Cover Land Cover percentage -

A4 Policy Brief

FOREST CHANGE DRIVERS AND IMPACTS POLICY BRIEF FOR BUKIDNON PROVINCE A key driver of deforestation and forest degradation in the Philippines is uncertainty regarding the exact drivers and sites of deforestation and forest degradation, which limits ability to develop targeted and effective conservation interventions. Forest figures are rarely available at the subnational level, more so at the landscape level. Forest cover estimates are available only up to the provincial level, while estimates for annual change rate in forest area is available only at the national level. To address this gap, ESSC embarked on an assessment of the drivers and impacts of forest cover change in Bukidnon, with particular focus on northern Pantaron Range, covering the municipalities of Impasugong and Cabanglasan, and the city of Malaybalay. The assessment uncovered both negative drivers and positive drivers, which co-exist in Bukidnon. KEY FINDINGS 1. Natural forests - critical to the sustainability of ecosystem services - are under pressure. a. Natural forests experienced a net decrease of almost 13,000 ha over 13 years, or almost 1,000 ha per year, largely due to degradation of mossy and primary forests. This translates to forest carbon losses of 2.88M Ct. b. Discounting the gains from natural regeneration in some areas, the province actually lost over 50,000 ha of mossy, primary and secondary forests over the period, or over 3,800 ha per year. c. Over 32,000 ha of mossy and primary forests became secondary or open forests. 2018 LAND COVER UPDATE OF BUKIDNON POLICY BRIEF 2. Major forest losses are in four blocks. -

"."1' Bestavailable Copy Determination of Development Fees Fortelecomubroadcast Companies Operating on Mt.~Tangladrangenaturalpar~

DETERMINATION OF DEVELOPMENT FEES FORTELECOMUBROADCAST COMPANIES OPERATING ON l MT. KITANGLAD RANGE NATURAL PARK Department of Environment and Natural Resources Philippine Economic - Environmental and Natural Resources Accounting System Environmental and Natural Resources Accounting Project Supported by the lmJD , ~ United States Agency for ~~[~ International Development II'tt*11"."1' BESTAVAILABLE COPY DETERMINATION OF DEVELOPMENT FEES FORTELECOMUBROADCAST COMPANIES OPERATING ON MT.~TANGLADRANGENATURALPAR~ ENRAP IV TECHNICAL PAPER by ENRAP-PAWB-PPSO Team2 September 1999 1 This document \\as made possible through a grant by the United States Agenc)' for International Development (USAID) under the terms and conditions ofContract No. 4924165-C.oo4042.oo. The opinions expressed herein are those ofthe authors and do not necessarily rellect the views of the USAID and collaborating institutions. This document may be reproduced or quoted in other pUblications as long as reference is made to the source. 'The ENRAI'-J'AWB-PPSO team is composed of: Jose E. Padilla, ENRAP Deputy Project Leader. Rina Maria P. Rosales, ENRAP Research Associate; T. Blastique, Sr. EMS. PAWB; S. Cabrera, CP II, PAWB; E. Corquero, Statistician L PAv,,"B; R. Buen, DMO IlL PPSO-DENR; and L Matubis, DMO II, PPSO-DENR. I TABLE OF CONTENTS Table ofContents List ofFigures and Tables Executive Surrunary 1. INTRODUCTION .••••..•.••.••.•..•.••••.••.••.•.••.••..•.•••••.••••..••••.•.•.•••....••••....•...•.•...1 2. OBJECTIVE OF THE STUDY •••••••.•.••..•.•••......••.•..•.••.••.••.•.•••••••..•.•..••••...•.•••.•1 3. FRAMEWORK. 1 3.1 Legal Framework '" ", '" ",.., 1 3.2 Proposed Fee System Guidelines ,. '" '" ,, _..2 3.3 Economic Framework: Willingness to Pay for Development Privileges .3 3.4 Survey Approaches and Methods , .4 4. STUDY OF THE RESULTS .5 4.1 Valuation ofthe Tenus and Conditions ofthe Memoranda ofAgreement. -

Climate Adaptation Through 'Payment for Ecosystem Services'

Ecosystem based Climate adaptation through adaptation ‘payment for ecosystem An innovative services’ in the Philippines river-basin scheme is strengthening Context and challenge including agri-plantations on steep slopes and mining – and climate resilience The Cagayan de Oro River drains the northern central part of the non-preparedness of the population.2 Action is needed to and addressing the island of Mindanao in the Philippines. From its headwaters protect people in the face of these mounting threats. biodiversity loss in the biodiversity-rich forest areas of the Kalatungan and by encouraging Kitanglad mountains, and across its 137,000-hectare Taking an ecosystem approach businesses to catchment, protected areas overlap with the ancestral The ecosystem approach promotes the integrated reward indigenous domains of indigenous peoples. Tensions have flared management of land, water and living resources in a way that peoples for between industry – including logging, mining and agribusiness achieves mutually compatible conservation and sustainable conserving – and indigenous communities in the mountains who rely on use, and delivers equitable benefits for people and nature.3 vital ecosystem subsistence and seasonal cash crops for survival, and who In this case, the region’s growing vulnerability reinforces services. This are alarmed by persistent encroachment into their forests.1 the urgent need for sustainable land-use management and initiative is a model ecosystem-based adaptation (EbA) to mitigate the impacts of for cooperative On the fertile mountainsides of the province of Bukidnon, future climate change-related disasters. resources flourishing agribusinesses such as pineapple and banana management that plantations are boosting the economy and providing On Mindanao, achieving this means building-up the employment for thousands of Mindanao ‘lowlanders’. -

Policy Paper

Ecosystems & Development Journal 7(1): 33-44 April 2017 ISSN 2012-3612 POLICY PAPER Analysis of the Multi-level Collaborative Management System in Mount Kitanglad Range Natural Park, Mindanao, Philippines John Parra ABSTRACT The overwhelming majority of government-designated protected areas in Asia have been thwarted with constraints to become effectively and equitably managed, and integrated into the broader landscapes. Significant constraints have included legal, governance, institutional, management capacities and financial aspects. In sharp contrast, the Philippines has over three decades of experience tackling the institutional mechanics of collaborative management. This paper analyzes the management arrangements of Mount Kitanglad Range Natural Park (MKRNP), one of the country’s best collaboratively managed protected areas. The analysis reveals a multi-level collaborative management system, involving two landscape collaborative management bodies, 13 protected area management working groups and the resurrection of local indigenous institutional bodies - the Council of Elders and the tribal guards. Some protected area working groups are effective whilst a few working groups have broad, and sometimes overlapping, mandates. Of high concern, both the landscape collaborative management bodies have low representation of these working groups and the indigenous communities themselves. Protected area staffing levels and resources are inadequate for providing technical support to effective multi-level collaborative management. Overall, MKRNP -

Establishing Protected Areas in the Philippines: Emerging Trends, Challenges and Prospects

Protected Areas in East Asia Rafael G. Senga Establishing Protected Areas in the Philippines: Emerging Trends, Challenges and Prospects The Philippine Protected Areas System: An Overview he Philippines has always been considered one of the major biodi- versity hotspots in the world. For while it boasts of one of the high- est levels of diversity and endemicity of life forms and some of the Tmost unique habitats in the world, it is also home to some of the planet’s critically endangered species of wildlife, such as the Philippine eagle, one of the most magnificent raptors in the world and our country’s symbol of biodiversity conservation. The country’s habitats and ecosystems, which play a major role in maintaining ecological balance and in the day-to-day lives of Filipinos, are in constant threat, mainly from unwise resource use and devel- opment paradigms that tend to increase pressure on the world’s already scarce resources. The recent book Megadiversity by Russell Mittermeier of Conservation International, which documents the world’s seventeen most important countries in terms of biodiversity, concludes that the Philippines belong to the top five biodiversity hotspots in the world. In view of these reasons, the There are more than 200 pro- Philippine government, in coopera- tected areas in the Philippines, tion with the public and international ranging from large natural parks, to donors, embarked on a mission to landscapes and seascapes, to wildlife establish a system of protected areas sanctuaries and small watersheds that in the country. The last remaining form the initial components of the representatives of Philippine habitats NIPAS Act. -

Adaptive and Collaborative Action Research As a Strategy Fo Biodiversity Conservation

Identification of Upland Rainforest Species in the Mount Kitanglad Range Natural Park Buffer Zone I Background The different intervention efforts in the Mt Kitanglad Natural Park has led to different results and further challenges for both the community and the natural environment. Some of these efforts provided results that helped the conservation of the biodiversity of the area. One of the milestones of these efforts is the proclamation of the whole area as Natural Park. However, most of the researches, biodiversity conservation projects and policy implementation met resistance from the community in varying degrees. These resulted to more pressure to the forest resources and more insecurity on the part of the community. Identification of upland forest species in the Mt. Kitanglad Natural Park Buffer Zone was a research intended to address both the need to understand and eventually protect the biodiversity of Mt. Kitanglad while understanding the Indigenous management practices as a mechanism for biodiversity conservation. The team recognized that biodiversity conservation is also a concern of this community and that they could be players instead of being the obstacle in conservation. The project “Identification of Upland Rainforest Species in Mt. Kitanglad”, is a Bronze Category winner of the BP Conservation Program of the year 2003. It is a technical and participatory forest research on the different species of endemic trees and plants within the buffer zone area of Mt. Kitanglad. These species were identified according to their local names, their scientific names as may be available, and their known properties and uses. The project also mapped the locations and conditions of these species and the conditions of their environs along with their neighboring flora and fauna. -

How the Talaandigs Regained Their Ancestral Lands

THE LAND INEQUALITY INITIATIVE CASE STUDY HOW THE TALAANDIGS REGAINED THEIR ANCESTRAL LANDS IN THE KALATUNGAN MOUNTAIN RANGE BY ROEL R. RAVANERA, THIEZA C. VERDIJO, XYLA MERCEDITA E. GUALBERTO THE LAND INEQUALITY INITIATIVE CASE STUDY HOW THE TALAANDIGS REGAINED THEIR ANCESTRAL LANDS STRATEGIC PARTNERS & CORE DONORS IN THE KALATUNGAN MOUNTAIN RANGE BY ROEL R. RAVANERA, THIEZA C. VERDIJO, XYLA MERCEDITA E. GUALBERTO ISBN: 978-92-95105-52-2 The contents of this work may be freely reproduced, The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors translated, and distributed. This work may not be utilised for and the individuals interviewed for this report. They do commercial purposes.For more information, please contact not constitute official positions of ILC and the initiative’s [email protected] or browse to: reference group. Published: October, 2020. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0 Editing: David Wilson. Design: Federico Pinci. CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS 6 MOVING FORWARD 29 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 7 Institutionalisation of IPRA 29 INTRODUCTION 9 Promoting landscape governance 30 Objectives 11 Enhancing internal governance systems 30 Methodology 11 REFERENCES AND BIBLIOGRAPHY 31 LAND INEQUALITY IN MINDANAO: A HISTORICAL OVERVIEW 13 Mindanao in the nineteenth century 13 Land settlement programmes 14 The arrival of agribusiness corporations 14 Impacts on native occupants 15 Current status of native occupants in Mindanao 15 Instituting reforms towards land equality 16 MILALITTRA’S REDEEMING JOURNEY 19 Legal recognition of -

AIMTEC Co-Creating Peace in Conflict-Affected Areas in Muslim

Copyright © November 2012 by The Asian Institute of Management All rights reserved. This book serves as an open source for all development practitioners with the condition that publisher is cited and notified in writing when material is used, reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods. All notifications should be addressed “Attention: Knowledge Manager,” at the address below. Published by The AIM-TeaM Energy Center for Bridging Leadership Of the AIM-Scientific Research Foundation, Inc. 3rd Level The Asian Institute of Management Joseph R. McMicking Campus 123 Paseo de Roxas MCPO Box 2095, 1260 Makati City, Philippines Email: [email protected] Telefax: (63 2) 892-4011 local 387 Cover photos courtesy of Romulo Quemado II, MBLP Fellow Editorial Team: Ma. Nieves R. Confesor, Miren Sanchez, Katrine Vicedo, Kloe Carvajal, Antonio Marfori, Jose Antonio Javier The TeaM Energy Center for Bridging Leadership would like to thank all the academic partners (past and current), the management team and faculty of the Asian Institute of Management and the AIM-Scientific Research Foundation, Inc., as well as all those on-the-ground who have dedicated themselves to peace-building in Mindanao and the country. This volume is an initial attempt to share some of the stories of the MBLP Cohort 1 Bridging Leaders and is dedicated to all the bridging leaders who continue to advocate for multi-sectoral collaboration in responding to complex social divides and to those who have passed on and left their work on peace-building for us to continue… Foreword “Bridging Leaders for the Co-Creation of Peace and Development in Mindanao, the Philippines and the World” by Nieves R. -

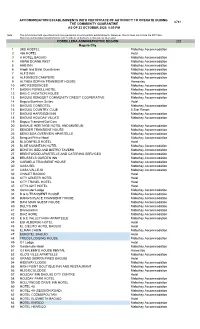

Aes with CAO.Xlsx

ACCOMMODATION ESTABLISHMENTS WITH CERTIFICATE OF AUTHORITY TO OPERATE DURING 6781 THE COMMUNITY QUARANTINE AS OF 23 OCTOBER 2020, 5:00 PM Note: The list includes both operational and non-operational accommodation establishments. Moreover, this list does not include the DOT Star- Rated Accommodation Establishments with Certificate of Authority to Operate for Staycation. CORDILLERA ADMINISTRATIVE REGION 203 Baguio City 1 3BU HOSTEL Mabuhay Accommodation 2 456 HOTEL Hotel 3 A HOTEL BAGUIO Mabuhay Accommodation 4 ABWE DOANE REST Mabuhay Accommodation 5 AHB INN Mabuhay Accommodation 6 Aleph and Dalet Guesthaven Mabuhay Accommodation 7 ALF'S INN Mabuhay Accommodation 8 ALFONSO'S CAMPSITE Mabuhay Accommodation 9 ALTHEA SOPHIA TRANSIENT HOUSE Homestay 10 ARC RESIDENCES Mabuhay Accommodation 11 BADEN POWELL HOTEL Mabuhay Accommodation 12 BAG-C VACATION HOUSE Mabuhay Accommodation 13 BAGUIO BENGUET COMMUNITY CREDIT COOPERATIVE Mabuhay Accommodation 14 Baguio Burnham Suites Hotel 15 BAGUIO CONDOTEL Mabuhay Accommodation 16 BAGUIO COUNTRY CLUB 5 Star Resort 17 BAGUIO HARRISON INN Mabuhay Accommodation 18 BAGUIO HOLIDAY VILLA'S Mabuhay Accommodation 19 Baguio Transient Dot Com 20 BANAUE HERITAGE HOTEL AND MUSEUM Mabuhay Accommodation 21 BENDER TRANSIENT HOUSE Mabuhay Accommodation 22 BENG BOA OVERVIEW APARTELLE Mabuhay Accommodation 23 Benguet Prime Hotel Mabuhay Accommodation 24 BLOOMFIELD HOTEL Hotel 25 BLUE MOUNTAIN HOTEL Mabuhay Accommodation 26 BONTOC BED AND BISTRO TAVERN Mabuhay Accommodation 27 BRENTWOOD APARTELLE AND CATERING SERVICES Mabuhay -

JBES-Vol-12-No-3-P-3

J. Bio. & Env. Sci. 2018 Journal of Biodiversity and Environmental Sciences (JBES) ISSN: 2220-6663 (Print) 2222-3045 (Online) Vol. 12, No. 3, p. 324-333, 2018 http://www.innspub.net RESEARCH PAPER OPEN ACCESS Responses of fruit bats to physical factors of selected forest patches in Mt. Kitanglad Range, Bukidnon, Philippines Richel Relox*1, Leonardo Florece1 1School of Environmental Science and Management, University of the Philippines Los Banos 2Department of Environmental Science and Technology, College of Science and Mathematics, University of Science and Technology of Southern Philippines, Cagayan de Oro City, Misamis Oriental Article published on March 30, 2018 Key words: Climate, Elevation, Forest, Fruit bats, Mt. Kitanglad. Abstract Fruit bat species playing a vital role in forest regeneration are affected by the physical factors in the remaining tropical forest patches influenced by the anthropogenic activities in Mt. Kitanglad Range. Fruit bats were surveyed in the selected forest patches along the increasing elevation characterized by varied temperature, humidity and rainfall. Mist-netting method was done to capture fruit bats for wet and dry seasons in a year in Mt. Kitanglad Range. A total of nine (9) species of fruit bats under Family Pteropodidae such as Ptenochirus jagori (Greater Musky Fruit Bat), Ptenochirus minor (Lesser Musky Fruit Bat), Alionycteris paucidentata (Mindanao Pygmy Fruit Bat), Haplonycteris fischeri (Philippine Pygmy Fruit Bat), Cynopterus brachyotis (Common Short-Nosed Fruit Bat), Rousettus amplexicaudatus (Geoffroy’s Rousette), Macroglossus minimus (Long-Tongue Nectar Bat), Harpyionycteris whiteheadi (Harpy Fruit Bat) and Megaerops wetmorei (White- Collared Fruit Bat) were recorded in all elevations in Mt. Kitanglad Range for both seasons. -

Study on Ancestral Domain Recognition and Management Within and Around the Mt

A Study on Ancestral Domain Recognition and Management Within and Around the Mt. Kitanglad Range National Park Vel J. Suminguit and Erlinda Burton Southeast Asia Policy Research Working Paper, No. 18 Acknowledgement This report is part of the ASB Project in Indonesia. The Asian Development Bank, under RETA 5711, financially supported this specific work. © Copyright ICRAF Southeast Asia Further information please contact: ICRAF SE-Asia Southeast Asian Regional Research Programme PO Box 161 Bogor 16001 Indonesia Tel: 62 251 625415, fax: 62 251 625416 Email: [email protected] ICRAF Southeast Asia website: http://www.icraf.cgiar.org/sea Cover design: Dwiati N. Rini Illustration design: Wiyono Declaimer This text is a ‘working paper’ reflecting research results obtained in the framework of ICRAF Southeast Asia project. Full responsibility for the contents remains with the authors. A Study on Ancestral Domain Recognition and Management Within and Around the Mt. Kitanglad Range National Park1 By Vel J. Suminguit2 and Erlinda Burton3 Introduction The Philippine government recognizes the critical importance of protecting and maintaining biodiversity for the present and future generations. This recognition is formally articulated in Section 2 of Republic Act 7586, otherwise known as "The National Integrated Protected Areas System Act of 1992" or NIPAS Act. At the same time, the Philippine government recognizes and promotes the rights of the Indigenous Cultural Communities (ICCs) or Indigenous Peoples (IPs), who are mostly occupants of the protected areas. The State’s recognition of the ICCs/IP’s rights is embodied in the Philippine Constitution (Art. II, Sec. 22) and reiterated in Section 13 of the NIPAS Act.