Weaving the Magic Wand for the IPMC Weavers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPCEN Report No. 3.Pdf

CITATION: Philippine Statistics Authority, 2015 Census of Population, Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density ISSN 0117-1453 ISSN 0117-1453 REPORT NO. 3 22001155 CCeennssuuss ooff PPooppuullaattiioonn PPooppuullaattiioonn,, LLaanndd AArreeaa,, aanndd PPooppuullaattiioonn DDeennssiittyy Republic of the Philippines Philippine Statistics Authority Quezon City REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES HIS EXCELLENCY PRESIDENT RODRIGO R. DUTERTE PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY BOARD Honorable Ernesto M. Pernia Chairperson PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY Lisa Grace S. Bersales, Ph.D. National Statistician Josie B. Perez Deputy National Statistician Censuses and Technical Coordination Office Minerva Eloisa P. Esquivias Assistant National Statistician National Censuses Service ISSN 0117-1453 FOREWORD The Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) conducted the 2015 Census of Population (POPCEN 2015) in August 2015 primarily to update the country’s population and its demographic characteristics, such as the size, composition, and geographic distribution. Report No. 3 – Population, Land Area, and Population Density is among the series of publications that present the results of the POPCEN 2015. This publication provides information on the population size, land area, and population density by region, province, highly urbanized city, and city/municipality based on the data from population census conducted by the PSA in the years 2000, 2010, and 2015; and data on land area by city/municipality as of December 2013 that was provided by the Land Management Bureau (LMB) of the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR). Also presented in this report is the percent change in the population density over the three census years. The population density shows the relationship of the population to the size of land where the population resides. -

Landslides and Flooding

2017/11/17 Welcome Delegates to the 53rd CCOP Annual Session!!! October 16 – 19, 2017 “The Role of Geosciences in Safeguarding Our Environment” 1 2017/11/17 Cebu City 2 2017/11/17 Geohazard Information: An Indispensable Tool for Land Use Planning and Disaster Risk Resiliency Implementation RD LEO VAN V. JUGUAN Mines and Geosciences Bureau 6 53rd CCOP Annual Session October 2017 Philippine Setting Prone to GEOHAZARDS 3 2017/11/17 Porphyry Cu belts Philippines Porphyry Cu belts • Within the Ring of Fire • Within the Earthquake Belt • Within the Pacific belt of tropical cyclone (average of 20 TYPHOONS A YEAR) 4 2017/11/17 Tectonic Map of the Philippines Source: PHIVOLCS Negros Oriental Earthquake 5 2017/11/17 1:50,000 SCALE GEOHAZARD MAPPING AND ASSESSMENT (2005-2010) The National Geohazard Assessment and Geohazard Mapping Program of the DENR Mines and Geosciences Bureau mandated the conduct of a geohazard mapping for the country as included in the Medium Term Philippine Development Plan of 2004-2010. HIGHHIGH LANDSLIDEFLOOD SUSCEPTIBILITY SUSCEPTIBILITYAreas likely to experience flood heights Unstableof 1.0 to areas,2.0 meters highly and/or susceptible flood to duration mass movementof more than. 3 days. These areas are immediately flooded during heavy rains of several hours. MODERATE LANDSLIDE SUSCEPTIBILITYMODERATE FLOOD SUSCEPTIBILITY StableAreas likelyareas to with experience occasional flood or localizedheights of to mass0.5 to movement. 1.0 meters and/or flood duration of 1 to 3 days. LOWLOW FLOODLANDSLIDE SUSCEPTIBILITY SUSCEPTIBILITYAreas likely to experience flood heights of <0.5 meter and/or flood duration of less Stable areas with no identified than 1 day. -

Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 1

COST OF DOING BUSINESS IN THE PROVINCE OF ILOILO 2017 Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 1 2 Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 F O R E W O R D The COST OF DOING BUSINESS is Iloilo Provincial Government’s initiative that provides pertinent information to investors, researchers, and development planners on business opportunities and investment requirements of different trade and business sectors in the Province This material features rates of utilities, such as water, power and communication rates, minimum wage rates, government regulations and licenses, taxes on businesses, transportation and freight rates, directories of hotels or pension houses, and financial institutions. With this publication, we hope that investors and development planners as well as other interested individuals and groups will be able to come up with appropriate investment approaches and development strategies for their respective undertakings and as a whole for a sustainable economic growth of the Province of Iloilo. Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 3 4 Cost of Doing Business in the Province of Iloilo 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword I. Business and Investment Opportunities 7 II. Requirements in Starting a Business 19 III. Business Taxes and Licenses 25 IV. Minimum Daily Wage Rates 45 V. Real Property 47 VI. Utilities 57 A. Power Rates 58 B. Water Rates 58 C. Communication 59 1. Communication Facilities 59 2. Land Line Rates 59 3. Cellular Phone Rates 60 4. Advertising Rates 61 5. Postal Rates 66 6. Letter/Cargo Forwarders Freight Rates 68 VII. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. These are also available as one exposure on a standard 35mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms international A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 Nortfi Zeeb Road. -

Iloilo Provincial Profile 2012

PROVINCE OF ILOILO 2012 Annual Provincial Profile TIUY Research and Statistics Section i Provincial Planning and Development Office PROVINCE OF ILOILO 2012 Annual Provincial Profile P R E F A C E The Annual Iloilo Provincial Profile is one of the endeavors of the Provincial Planning and Development Office. This publication provides a description of the geography, the population, and economy of the province and is designed to principally provide basic reference material as a backdrop for assessing future developments and is specifically intended to guide and provide data/information to development planners, policy makers, researchers, private individuals as well as potential investors. This publication is a compendium of secondary socio-economic indicators yearly collected and gathered from various National Government Agencies, Iloilo Provincial Government Offices and other private institutions. Emphasis is also given on providing data from a standard set of indicators which has been publish on past profiles. This is to ensure compatibility in the comparison and analysis of information found therewith. The data references contained herewith are in the form of tables, charts, graphs and maps based on the latest data gathered from different agencies. For more information, please contact the Research and Statistics Section, Provincial Planning & Development Office of the Province of Iloilo at 3rd Floor, Iloilo Provincial Capitol, and Iloilo City with telephone nos. (033) 335-1884 to 85, (033) 509-5091, (Fax) 335-8008 or e-mail us at [email protected] or [email protected]. You can also visit our website at www.iloilo.gov.ph. Research and Statistics Section ii Provincial Planning and Development Office PROVINCE OF ILOILO 2012 Annual Provincial Profile Republic of the Philippines Province of Iloilo Message of the Governor am proud to say that reform and change has become a reality in the Iloilo Provincial Government. -

International Milkfish Workshop Conference, May 19-22, 1976, Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines

International Milkfish Workshop Conference, May 19-22, 1976, Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines Item Type book Publisher Aquaculture Department, Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center Download date 11/10/2021 06:00:54 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/40415 International Milkfish Workshop Conference, May 19- 22, 1976, Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines Date published: 1976 To cite this document : International Milkfish Workshop Conference, Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center., & International Development Research Centre (Canada). (1976). International Milkfish Workshop Conference, May 19-22, 1976, Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines. Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines: Aquaculture Department, Southeast Asian Fisheries Development Center. Keywords : Milkfish culture, Conferences, Behaviour, Feeding behaviour, Ecology, Biology, Fish eggs, Fishery surveys, Ichthyoplankton surveys, Larvae, Sexual maturity, Sexual reproduction, Natural populations, Incubation, Hatching, Rearing, Larval development, Predators, Husbandry diseases, Biological stress, Fish physiology, Fishery institutions, Research institutions, Chanos chanos, Milkfish To link to this document : http://hdl.handle.net/10862/3380 Share on : PLEASE SCROLL DOWN TO SEE THE FULL TEXT This content was downloaded from SEAFDEC/AQD Institutional Repository (SAIR) - the official digital repository of scholarly and research information of the department Downloaded by: [Anonymous] On: January 17, 2019 at 11:19 AM CST Follow us on: Facebook | Twitter | Google Plus | Instagram Library & Data -

ANALYSIS of the CHARCOAL VALUE CHAIN in ILOILO CITY (Final Report)

ANALYSIS OF THE CHARCOAL VALUE CHAIN IN ILOILO CITY (Final Report) BUILDING LOW EMISSION ALTERNATIVES TO DEVELOP ECONOMIC RESILIENCE AND SUSTAINABILITY PROJECT (B-LEADERS) September 2017 This document was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). It was prepared by the Building Low Emission Alternatives to Develop Economic Resilience and Sustainability (B- LEADERS) Project implemented by RTI International for USAID Philippines. ANALYSIS OF THE CHARCOAL VALUE CHAIN IN ILOILO CITY (Final Report) BUILDING LOW EMISSION ALTERNATIVES TO DEVELOP ECONOMIC RESILIENCE AND SUSTAINABILITY PROJECT (B-LEADERS) September 2017 DISCLAIMER The author’s views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ··································································· I LIST OF TABLES ········································································ III LIST OF FIGURES ······································································ III ACRONYMS ················································································ IV EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ································································· 1 I. INTRODUCTION ································································ 4 1.1. Objectives ............................................................................................................ 6 1.2. Scope and Limitations ....................................................................................... -

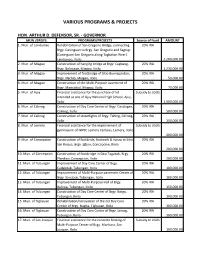

Various Programs & Projects

VARIOUS PROGRAMS & PROJECTS HON. ARTHUR D. DEFENSOR, SR. - GOVERNOR MUN./BRGYS. PROGRAMS/PROJECTS Source of Fund AMOUNT 1. Mun. of Lambunao Rehabilitation of San Gregorio Bridge, connecting 20% IRA Brgy. Caninguan to Brgy. San Gregorio and Sagcup (Caninguan-San Gregorio along Tagbakan River) Lambunao, Iloilo 2,200,000.00 2. Mun. of Miagao Construction of hanging bridge at Brgy. Cagbang- 20% IRA Brgy. Bolocaue, Miagao, Iloilo 1,230,000.00 3. Mun. of Miagao Improvement of footbridge of Sitio Buenapantao, 20% IRA Brgy. Naclub, Miagao, Iloilo 50,000.00 4. Mun. of Miagao Construction of the Multi-Purpose pavement of 20% IRA Brgy. Maricolcol, Miagao, Iloilo 70,000.00 5. Mun. of Ajuy Financial assistance for the purchase of lot Subsidy to LGUS intended as site of Ajuy National High School, Ajuy, Iloilo 1,000,000.00 6. Mun. of Calinog Construction of Day Care Center of Brgy. Caratagan, 20% IRA Calinog, Iloilo 500,000.00 7. Mun. of Calinog Construction of streetlights of Brgy. Tahing, Calinog, 20% IRA Iloilo 150,000.00 8. Mun. of Lemery Financial assistance for the improvement of Subsidy to LGUS gymnasium of NIPSC Lemery Campus, Lemery, Iloilo 400,000.00 9. Mun. of Concepcion Construction of footbride, footwalk & riprap at Sitio 20% IRA San Roque, Brgy. Igbon, Concepcion, Iloilo 200,000.00 10. Mun. of Concepcion Construction of footbridge in Sitio Tagabak, Brgy. 20% IRA Plandico, Concepcion, Iloilo 200,000.00 11. Mun. of Tubungan Improvement of Day Care Center of Brgy. 20% IRA Cadabdab, Tubungan, Iloilo 100,000.00 12. Mun. of Tubungan Improvement of Multi-Purpose pavement Center of 20% IRA Brgy. -

Iloilo Antique Negros Occidental Capiz Aklan Guimaras

Sigma Kalibo Panitan Makato Handicap International Caluya PRCS - IFRC Don Bosco Network Ivisan PRCS - IFRC Humanity First Tangalan CapizNED CapizNED Don Bosco Network PRCS - IFRC CARE Supporting Self Recovery PRAY PRCS - IFRC IOM Citizens’ Disaster Response Center New Washington CapizNED IOM Region VI Humanity First Caritas Austria Don Bosco Network PRAY PRAY of Shelter Activities Malay PRAY World Vision Numancia PRCS - IFRC Humanity First PRCS - IFRC Buruanga IOM PRCS - IFRC by Municipality (Roxas) PRCS - IFRC Nabas Buruanga Don Boxco Network Balasan Pontevedra Altavas Roxas City PRCS - IFRC Ibajay HEKS - TFM 3W map summary Nabas Libertad IOM Region VI Caritas Austria IOM R e gion VI World Vision PRCS - IFRC CapizNED Tangalan CapizNED World Vision Citizens’ Disaster Response Center Produced April 14, 2014 Pandan PRAY Batad Numancia Don Bosco Network IOM Region VI CARE IRC Makato PRCS - IFRC PRCS - IFRC Malinao Makato Kalibo Panay MSF-CH Don BoSco Network Batan Humanity First Humanity First This map depicts data PRCS - IFRC Lezo IOM Caritas Austria Relief o peration for Northern Iloilo World Vision Lezo PRCS - IFRC CapizNED Solidar Suisse gathered by the Shelter CARE PRCS - IFRCNew Washington IOM Region VI Pilar Cluster about agencies Don Bosco Network HEKS - TFM Malinao HEKS - TFM Carles who are responding to Sebaste Banga Caritas Austria IOM Region VI PRAY DFID - HMS Illustrious Sebaste World Vision Welt Hunger Hilfe Typhoon Yolanda. PRCS - IFRC Concern Worldwide IOM Banga Citizens’ Disaster Response CenterRoxas City Humanity First IOM Region VI Batan Humanity First MSF-CH Carles Any agency listed may Citizens’Panay Disaster Response Center Save the Children Region VI Altavas Ivisan ADRA Ayala Land have projects at different Madalag AklanBalete SapSapi-Ani-An stages of completion (e.g. -

Infrastructure

Infrastructure Php 3,968.532 M Roads & Bridges Php 2,360.126 M Sch bldgs/classrooms Php 958.116 M Electrical Facilities 297.400 M Health Facilities and Others Php 352.891M Cost of Assistance Provided by Government Agencies/LGUs/NGOs (TAB E) NDCC - Php 16,233,375 DSWD - Php 26,018,019 DOH - Php 15,611,099 LGUs - Php 19,874,903 NGOs - Php 2,595,130 TOTAL - Php 80,332,527 International and Local Assistance/Donations (Tab F) Total International/Donations Cash - US $ 510,000 Aus $ 500,000. In kind - Php 8,000,000 (generator sets, and other non-food items NFI’s) US $ 650,000 (relief flight) Local Assistance/Donations Cash - Php 1,025,000 In Kind - Php 95,539 (assorted relief commodities) 90 sets disaster kits Areas Declared under a State of Calamity by their respective Sanggunians : 10 Provinces Albay, Antique, Iloilo, Aklan, Capiz, Sarangani, Sultan Kudarat, North Cotabato, Marinduque and Romblon 8 Municipalities Paombong and Obando in Bulacan; Carigara, Leyte; and Lake Sebu, Surallah, Sto. Nino and Tiboli in South Cotabato, and San Fernando, Romblon 3 Cities Cotabato City, Iloilo City and Passi City 9 Barangays (Zamboanga City) – Vitali, Mangusu, San Jose Gusu, Tugbungan, Putik, Baliwasan, Tumaga, Sinunuc and Sta. Catalina 2 II. Actions Taken and Resources Mobilized by Agencies: Relief and Recovery Operations NDCC-OPCEN Facilitated release of 17,790 sacks of rice in 11 regions (I – 200, III – 950, IV-A – 1,300, IV-B – 1,150, V – 250, VI – 11,300, VII – 500, VIII – 500, XII – 740, NCR – 300, ARMM – 600) amounting to P16,233,375.00 AFP-PAF Disaster Response Transported the 15 th sortie (assorted goods and medicine boxes) from DZRH & PAGCOR to Iloilo III. -

Weather Observation at Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines from 1977 to 1980

Technical eportR No. 8 March 1981 Weather Observation at Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines From 1977 to 1980 Hiroshi Motoh, Noel Solis, Edna Caligdong Milagros Gelangre and Fely Boblo AQUACULTURE DEPARTMENT SOUTHEAST ASIAN FISHERIES DEVELOPMENT CENTER Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines Weather Observations at Tigbauan, Iloilo, Philippines, From 1977 to 1980 Hiroshi Motoh, Noel Solis, Edna Caligdong, Milagros Gelangre and Fely Boblo INTRODUCTION The Philippines lies in the tropic region from approximately 5 to 19°N latitude. The weather condition is relatively constant compared with countries in the temperate zone such as Japan. However, through careful observations, there is a slight difference in such weather parameter as air temperature during the monsoon season. When estab lishing and operating fishponds for bangos and sugpo culture, it is very important to know the weather conditions particularly wind direction, water temperature and the amount of rainfall, because these factors directly affect yields. Weather observation was initiated aiming at the following purposes: i) Train technical staff of Aquaculture Department (AQD) of the SEAFDEC in terms of knowing the method and practice of weather observations based on the daily activity. ii) Provide the basic data of weather as well as sea conditions which are necessary for the proper operation of various hatcheries, pond and cage design-construction and operation, and for the ecological study of com mercially important marine species. iii) Gather meteorological data through actual daily observations for the basic study such as those needed by students in the university. MATERIAL AND METHOD Daily weather observation was preliminarily initiated on the middle of June 1977 to familiarize the staff members who were scheduled to conduct the daily observations. -

DPWH ILOILO 1ST DISTRICT ENGINEERING OFFICE) Indicative Annual Procurement Plan for FY 2021 (CIVIL WORKS, GOODS and CONSULTING SERVICES)

(DPWH ILOILO 1ST DISTRICT ENGINEERING OFFICE) Indicative Annual Procurement Plan for FY 2021 (CIVIL WORKS, GOODS AND CONSULTING SERVICES) Schedule for Each Procurement Activity Estimated Budget (PhP) Is this an Early Procurement PMO/ Procurement Source of Remarks Code (PAP) Mode of Procurement Activity? Advertisement/Posting Submission/Opening of Project End-User Notice of Award Contract Signing Funds Total MOOE CO (brief description of Project) (Yes/No) of IB/REI Bids Iloilo-Antique Rd - K0011 + 721- K0011 + 921, K0033 + 310 - K0033 + 665, K0035 + 021 - K0035 + 235, K0064 Construction Preventive Maintenance - YES Competitive Bidding 11/15/2020 12/5/2020 2/8/2021 2/18/2021 GoP 11,000,000.00 11,000,000 + 116 - K0064 + 682, K0064 + 842 - K0065 + 301, Section Secondary Roads K0066 + 000 - K0066 + 879 Construction Preventive Maintenance - Iloilo-Antique Rd - K0016 + 845 - K0017 + 646 YES Competitive Bidding 11/15/2020 12/5/2020 2/8/2021 2/18/2021 GoP 10,000,000.00 10,000,000.00 Section Secondary Roads Tiolas-Sinugbuhan Rd - K0063+463 - K0063+926, Construction Preventive Maintenance - YES Competitive Bidding 11/15/2020 12/5/2020 2/8/2021 2/18/2021 GoP 1,027,000.00 1,027,000.00 K0067+866 - K0068+111 Section Secondary Roads Oton-Buray-Sta Monica-Sn Antonio-Sn Miguel Rd - Construction Preventive Maintenance - Tertiary YES Competitive Bidding 11/15/2020 12/5/2020 2/8/2021 2/18/2021 GoP 10,145,000.00 10,145,000 K0011 + 000 - K0012 + 419, K0013 + 663 - K0015+ 536 Section Roads Oton-Mambog-Cabolo-an-Abilay-Sn Jose Rd - K0013 + Construction Preventive