Scottish Bathing Waters Report 2004

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Argyll Bird Report with Sstematic List for the Year

ARGYLL BIRD REPORT with Systematic List for the year 1998 Volume 15 (1999) PUBLISHED BY THE ARGYLL BIRD CLUB Cover picture: Barnacle Geese by Margaret Staley The Fifteenth ARGYLL BIRD REPORT with Systematic List for the year 1998 Edited by J.C.A. Craik Assisted by P.C. Daw Systematic List by P.C. Daw Published by the Argyll Bird Club (Scottish Charity Number SC008782) October 1999 Copyright: Argyll Bird Club Printed by Printworks Oban - ABOUT THE ARGYLL BIRD CLUB The Argyll Bird Club was formed in 19x5. Its main purpose is to play an active part in the promotion of ornithology in Argyll. It is recognised by the Inland Revenue as a charity in Scotland. The Club holds two one-day meetings each year, in spring and autumn. The venue of the spring meeting is rotated between different towns, including Dunoon, Oban. LochgilpheadandTarbert.Thc autumn meeting and AGM are usually held in Invenny or another conveniently central location. The Club organises field trips for members. It also publishes the annual Argyll Bird Report and a quarterly members’ newsletter, The Eider, which includes details of club activities, reports from meetings and field trips, and feature articles by members and others, Each year the subscription entitles you to the ArgyZl Bird Report, four issues of The Eider, and free admission to the two annual meetings. There are four kinds of membership: current rates (at 1 October 1999) are: Ordinary E10; Junior (under 17) E3; Family €15; Corporate E25 Subscriptions (by cheque or standing order) are due on 1 January. Anyonejoining after 1 Octoberis covered until the end of the following year. -

Caithness and Sutherland Local Development Plan Report by Director of Development and Infrastructure

1 The Highland Council Agenda 9. Item Sutherland County Committee Report CC/ Caithness Committee No 16/16 30 August 2016 31 August 2016 Caithness and Sutherland Local Development Plan Report by Director of Development and Infrastructure Summary This report presents a summary of issues raised in comments received on the Proposed Caithness and Sutherland Local Development Plan (CaSPlan) and seeks approval for the Council’s response to these issues and next steps. In accordance with the Council’s Scheme of Delegation, the two Local Committees are asked to consider the report and decide on these matters. The recommended Council position is to defend the Proposed Plan, subject to only minor modifications, which would mean that the next stage would be submission to Ministers and progression to Examination. Other options would involve further consultation on a Modified Plan. The report explains the implications of each way forward. 1. Background 1.1 The Caithness and Sutherland Local Development Plan (CaSPlan) is the second of three area local development plans to be prepared by the Highland Council. Together with the Highland-wide Local Development Plan (HwLDP) and more detailed Supplementary Guidance, CaSPlan will form part of the Council’s Development Plan against which planning decisions will be made in the Caithness and Sutherland area. 1.2 The Proposed Plan consultation for CaSPlan ran from 22 January to 18 March 2016. Around 201 organisations or individuals responded, raising around 636 comments. This includes a few comments received on the associated Proposed Action Programme. All these comments have been published on the development plans consultation portal consult.highland.gov.uk. -

MSBO Report 2016

Machrihanish Seabird Observatory Report 2016 Machrihanish Seabird Observatory 2016 Report 1 Machrihanish Seabird Observatory Report 2016 Machrihanish Seabird Observatory (MSBO) SW Kintyre – Argyll PA28 6PZ Established September 1993 2016 Report Compiled by Eddie Maguire Unless stated photographs in this report are by the warden Cover photos – Dunlins / MSBO and a juvenile Northern Gannet The beautiful village of Machrihanish / Photo – Stuart Andrew Contents... Introduction and Highlights 2016... 4 Overland passage of Northern Gannets in south Argyll... 4 Unprecedented autumn passage of Curlew Sandpipers at Machrihanish... 5 North American duck off MSBO... 6 Monthly Reports... 6 Acknowledgements... 53 Movements of Goldfinch in Argyll 2009 – 2016... 54 2 Machrihanish Seabird Observatory Report 2016 Sub-adult Pomarine Skua 4th May First-winter Iceland Gull 24th March 3 Machrihanish Seabird Observatory Report 2016 Introduction to 2016 Report... The MSBO was manned daily 1st March – 31 October with casual observations later. The 2016 Report portrays the year with a monthly summary of the main ornithological events accompanied by a selection of 83 photographs. Visit www.machrihanishbirdobservatory.org.uk Highlights of the year... Resolute daily observations ultimately produced records of scarce/unusual species and excellent totals of many regular passage visitors. Without doubt, the most extraordinary events of the year involved an 8km overland passage by almost three hundred adult Northern Gannets and an unprecedented passage of Curlew Sandpipers. Summary of overland passage by Northern Gannets in south Argyll... During August-October 2016, the MSBO warden arranged regular surveillance at Campbeltown harbour, S Kintyre, Argyll to determine the scale of overland passage by Northern Gannets Morus bassanus. -

Bathing Water Profile for Thurso Bay (Central)

Bathing Water Profile for Thurso Bay (Central) Thurso, Scotland _____________ Current water classification https://www2.sepa.org.uk/BathingWaters/Classifications.aspx _____________ Description Thurso Bay (Central) bathing water is situated on the north coast of Scotland adjacent to the town of Thurso. The designated bay is less than 1 km long and extends from Rockwell Point in the west to Little Ebb in the east. The beach is popular with bathers and water sport enthusiasts. During high and low tides the approximate distance to the water’s edge can vary from 0–160 metres. The sandy beach slopes gently towards the water. Site details Local authority Highland Council Year of designation 2008 Water sampling location ND 11697 68860 EC bathing water ID UKS7616085 Catchment description The catchment draining into the Thurso bathing water extends to 487 km2. The catchment varies in topography from hills (maximum elevation 440 metres) in the south to the low-lying land (average elevation 5 metres) along the coast. The main river within the bathing water catchment is the River Thurso which discharges to the east of the designated bathing water. Land use in the catchment is mainly split between rural land and bog. The principal rural land uses in the area are improved grassland (14%), shrub (12%) and coniferous woodland (10%). The upper catchment around Halkirk is mainly sheep farming with beef farming around Thurso. Less than one percent of the bathing water catchment is urban. The main population centre is the town of Thurso situated adjacent to the bathing water. Population density outside of Thurso is generally low (Map 2). -

Salmon Migrations

SOME PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS ON THE MIGRATIONS OF SALMON (SALMO SALAR) ON THE COASTS OF SCOTLAND. BY W. J. M. MENZIES, F. R. S. E. Inspector of Salmon Fisheries of Scotland. — 18 — IXED nets for the capture of salmon were from low water mark. This practice of “out- first used on the coast of Scotland just overrigging” the nets is extending and this year it was successfully employed at the experimental marking F one hundred and ten years ago (ca. 1827) station on the west coast where only single nets and from the success which they immediately are still usually employed. obtained, and which has been continued, it is evident that the salmon in the course of their sea When lines of nets are fished in this fashion life come close inshore. At first no doubt it was and two lines of six or more nets each are fished not realised whether the fish were feeding or were with equal success within two hundred yards or so on migration when captured. In later years it has of each other, it is clear that the migration of the become clear that the fish have ceased feeding salmon along the coast cannot be a simple progress before they reach the coast and that they may be in one direction and in a comparatively straight line. considered to be then on their way from the feeding The Figures 1 and 2 are charts of St. Cyrus and to the spawning grounds. For long it was thought Lunan Bays showing the spacing of the nets and the that the fixed nets were only of importance to number used at each position. -

Discover Thurso Tourism Workshops—Learning Summary

Discover Thurso Tourism Workshops—Learning Summary Workshop Purpose The rationale behindLocalisation Workshops is to connect the peo- ple who interact with our visitors to the information than can enhance their time here and create a better sense of Thurso. Ever heard someone say Thurso under-sells itself? Discover Thurso workshops aim to empower people to not only sell the town, but to champion Thurso’s tourism offering. Why Localisation No other organisation across Scotland is responsible for or even qualified to specifically promote Thurso; it’s something we have to do ourselves. Many of our visitors may just be passing through on the NC500, or staying 1-night before heading to Orkney, but they’re a captive audience—they’re looking for things like golden sand beaches, 2,000 year old monuments, castles, whisky, Scottish food, the Northern Lights, traditional music and so on. Things we can offer readily. If we localise our knowledge and our conversations with tourists—that is, to focus them on Thurso— we’re spreading a positive message about the town to people who, even if they don’t come back to Scotland one day, will definitely be telling friends about wee places that caught their eye on the way round. What you can do… 1. Engage Tourists—Dornoch scores incredibly well when it asks its visitors whether they’d consider returning to the town, in large part to their hospitality. They asked their visitors what the most positive aspect to their stay in Dornoch was—the answer? Engaging with friendly locals. 2. Know the town, make recommendations—A Thurso bartender recently made a couple’s day when she was able to recommend Wolfburn and Dunnet Bay Distillery tours as activities for a rainy day. -

Highlands and Islands Enterprise

HIGHLANDS AND ISLANDS ENTERPRISE A FRAMEWORK FOR DESTINATION DEVELOPMENT AMBITIOUS FOR TOURISM CAITHNESS AND NORTH SUTHERLAND Full Report – Volume II (Research Document) (April 2011) TOURISM RESOURCES COMPANY Management Consultancy and Research Services In Association with EKOS 2 LA BELLE PLACE, GLASGOW G3 7LH Tel: 0141-353 1143 Fax: 0141-353 2560 Email: [email protected] www.tourism-resources.co.uk Management Consultancy and Research Services 2 LA BELLE PLACE, GLASGOW G3 7LH Tel: 0141-353 1143 Fax: 0141-353 2560 Email: [email protected] www.tourism-resources.co.uk Ms Rachel Skene Head of Tourism Caithness and North Sutherland Highlands and Islands Enterprise Tollemache House THURSO KW14 8AZ 18th April 2011 Dear Ms Skene AMBITIOUS FOR TOURISM CAITHNESS AND NORTH SUTHERLAND We have pleasure in presenting Volume II of our report into the opportunities for tourism in Caithness and North Sutherland. This report is in response to our proposals (Ref: P1557) submitted to you in October 2010. Regards Yours sincerely (For and on behalf of Tourism Resources Company) Sandy Steven Director Ref: AJS/IM/0828-FR1 Vol II Tourism Resources Company Ltd Reg. Office: 2 La Belle Place, Glasgow G3 7LH Registered in Scotland No. 132927 Highlands & Islands Enterprise Volume II Tourism Resources Company Ambitious for Tourism Caithness and North Sutherland April 2011 AMBITIOUS FOR TOURISM CAITHNESS AND NORTH SUTHERLAND – VOLUME II APPENDICES I Audit of Tourism Infrastructure Products / Services and Facilities by Type Electronic Database Supplied -

Campbeltown, Oban & the Isle of Mull

Campbeltown, Oban & the Isle of Mull To the South of Fort William down Loch Linnhe is Oban. This small town is situated in a beautiful crescent shaped bay and is known as the ‘Gateway to the Isles’ and the ‘Seafood capital of Scotland’. Ferry services run from here to Coll, Port Askaig, Castlebay, Colonsay, Lismore, Tiree, Mull, Barra and South Uist in the outer islands. Oban makes a brilliant touring base for wanting to explore these further destinations but there are also lots to see in the town itself. Spend your days exploring castles, gardens, beaches and forests around Oban and make sure to try some of the top-quality seafood. From Oban travel South and take in the coastal scenery as you approach Tarbert which has impressive wildlife, including birds of prey and deer. Continue on the only road around the Kintyre Peninsula and you will arrive in Campbeltown, home to a few distilleries including Glen Scotia and Springbank. Visitors can enjoy a guided tour around and find out the secrets of whisky making in Kintyre. Places to visit Tobermory This is the main town on the island of Mull. The port with its colourful harbor-front buildings was setting of a children’s television show. Take the ferry across from Oban to reach this town. New Picture Tobermory PA75 6QF www.tobermory.co.uk Oban Chocolate Company Relax and indulge on your visit to the factory where you can shop and watch mouth watering chocolates being hand-made alongside a delicious hot chocolate or coffee. 34 Corran, Esplanade, Oban PA34 5PS www.obanchocolate.co.uk Tel: 01631 566099 Springbank Distillery Experience tales and tastes as you journey through the distillery and its hometown. -

16 Major Disasters and Accidents 59 17 Material Assets 61 18 Cumulative Impacts 63 19 Conclusion 64

Redevelopment of St. Ola Pier EIA Scoping Report (ESR) July 2018 Redevelopment of St. Ola Pier CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 PROJECT DESCRIPTION 4 3 COASTAL PROCESSES 7 4 FLOOD RISK 9 5 MARINE BIODIVERSITY 12 6 WATER QUALITY 18 7 TERRESTRIAL BIODIVERSITY AND ORNITHOLOGY 22 8 TRANSPORTATION 27 9 AIR QUALITY AND CLIMATE 31 10 NOISE AND VIBRATION 36 11 WASTE MANAGEMENT 40 12 SOILS, GEOLOGY AND CONTAMINATION 42 13 CULTURAL HERITAGE 45 14 LANDSCAPE AND VISUAL 49 15 POPULATION, HUMAN HEALTH AND SOCIO-ECONOMICS 55 16 MAJOR DISASTERS AND ACCIDENTS 59 17 MATERIAL ASSETS 61 18 CUMULATIVE IMPACTS 63 19 CONCLUSION 64 Appendix 1.1 EIA Screening Opinion Correspondences Appendix 1.2 Existing Scrabster Harbour Layout Appendix 1.3 Proposed list of Consultees Appendix 2.1 Preferred Layout Drawing Appendix 2.2 Location of Sea Disposal Site Appendix 11.1 Operational Waste and Landfill Sites Appendix 13.1 Correspondence with Highland Council Historic Environment Team i EIA Scoping Report (ESR) July 2018 Redevelopment of St. Ola Pier 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 This Environmental Impact Assessment Scoping Report (ESR) has been prepared by RPS on behalf of Scrabster Harbour Trust (SHT) in respect of the proposed redevelopment of St. Ola Pier, Scrabster Harbour, Thurso, Caithness. An EIA Screening Opinion on the proposed redevelopment issued from Marine Scotland Licensing Operations Team (MSLOT) in March 2018 (Appendix 1.1). This Opinion determined the proposed redevelopment to be EIA development under The Marine Works (Environmental Impact Assessment) (Scotland) Regulations 2017 (the EIA Regulations), and as such an Environmental Impact Assessment must be carried out. -

Bleachfield Farm by Campbeltown, Argyll & Bute

BLEACHFIELD FARM BY CAMPBELTOWN, ARGYLL & BUTE BLEACHFIELD FARM BY CAMPBELTOWN ARGYLL & BUTE A compact livestock farm set in some of the finest ground found on the Kintyre Peninsula Campbeltown 2 miles Lochgilphead 54 miles Glasgow 142 miles • Traditional 5-bedroom farmhouse • Traditional courtyard • Range of modern and traditional outbuildings • 156.6 acres of productive grazing and silage ground For Sale as a Whole About 63.3 Ha (156.6 Acres) in all Suite C Stirling Agricultural Centre Stirling FK9 4RN 01786 434600 [email protected] GENERAL Modern Sheds Bleachfield Farm is an extensive stock rearing farm situated in some of the best agricultural land found on To the west side of the steading is an extensive range of modern farm buildings, ideal for handling cattle, the Kintyre Peninsula on the west coast of Scotland. Machrihanish Bay and the Atlantic Coast lie only a which benefit from electric power and light, water troughs and concrete or stone flooring. The sheds also short distance to the north. The small settlement of Drumlemble lies a short distance away from the farm, benefit from a system of gated cattle handling facilities. on the B842 and it has a primary school. Campbeltown lies 2 miles to the east, where a large range of shops, schools and professional services can be found. Campbeltown Airport is also nearby and offers Large span cattle shed : 47.0 m x 23.0 m (approx.) Concrete portal frame with timber built lean-to regular flights to Glasgow. Glasgow is accessible via the A83 from Campbeltown and is 142 miles distant, sections. -

NEWSLETTER of the ORKNEY FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY Issue No 57 March 2011

NEWSLETTER OFSIB THE ORKNEY FAMILY FOLK HISTORY SOCIETY NEWSISSUE No 57 MARCH 2011 graphics John Sinclair 2 NEWSLETTER OF THE ORKNEY FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY Issue No 57 March 2011 ORKNEY FAMILY HISTORY NEWSLETTER Issue No 57 March 2011 CONTENTS FRONT COVER Spring From has Sprung the chair PAGE 2 From the Chair As the economic recession starts to impact on people’s lives, PAGE 3 there are likely to be many changes over this next year. In Tumbledown Orkney, the Council has been consulting with the Orkney 'UPPERTOWN' community under the banner of “Tough Times – Tough Choices”. When researching one’s family history you do not PAGES 4,5 & 6 have to go back that many years when the same could have Capt. John Robert Arthurson equally described the lives of our forbearers. In reality their predicament was probably 20 times worse than what we have to face. Our committee is now back to full strength and we welcome Morag Sinclair on to our PAGE 7 Orkney Picnic. committee. Membership continues to grow with the Society now with over 2,500 members Tumbledown since its inception. Correction The 2011 programme began in February with a talk by David Eaton on “Momento Mori” – (How we commemorate the Dead). His slide show highlighted various styles of gravestones and tombs; their inscriptions, symbolism and other aspects of how past PAGE 8 The 1911 Census generations have commemorated their ancestor’s lives and deaths. Our March programme again explores the web with an emphasis of “Emigration Records” PAGE 9 and other new sites. There continues to be expansion in the range of Website resources 'Life un the targeted at the family history market. -

2 Burnside.Indd

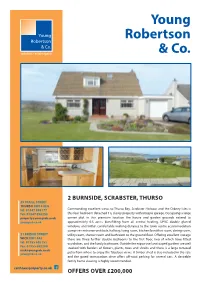

Young Young Robertson Robertson & Co. solicitors • estate agents & Co. 2 BURNSIDE, Scrabster, THURSO 29 TRAILL STREET THURSO KW14 8EG tel: 01847 896177 Commanding excellent views to Thurso Bay, Scrabster Harbour and the Orkney Isles is fax: 01847 896358 this four bedroom detached 1½ storey property with integral garage. Occupying a large [email protected] corner plot in this premium location the house and garden grounds extend to youngrob.co.uk approximately 0.5 acres. Benefitting from oil central heating, UPVC double glazed windows and within comfortable walking distance to the town centre accommodation comprises entrance vestibule, hallway, living room, kitchen/breakfast room, dining room, 21 BRIDGE STREET utility room, shower room and bathroom to the ground floor. Offering excellent storage WICK KW1 4AJ there are three further double bedrooms to the first floor, two of which have fitted tel: 01955 605151 wardrobes, and the family bathroom. Outside the expansive landscaped gardens are well fax: 01955 602200 stocked with borders of flowers, plants, trees and shrubs and there is a large terraced [email protected] youngrob.co.uk patio from where to enjoy the fabulous views. A timber shed is also included in the sale and the gated tarmacadam drive offers off-road parking for several cars. A desirable family home viewing is highly recommended. caithnessproperty.co.uk f OFFers OVer £200,000 Vestibule 1.08m x 0.98m 3’6” x 3’2” General Information Partially glazed timber front door. Tiled flooring. 15 panel glazed door to The floor coverings, curtains and blinds as fitted are included in the sale.