The Basics of Digestion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coffee and Its Effect on Digestion

Expert report Coffee and its effect on digestion By Dr. Carlo La Vecchia, Professor of Medical Statistics and Epidemiology, Dept. of Clinical Sciences and Community Health, Università degli Studi di Milano, Italy. Contents 1 Overview 2 2 Coffee, a diet staple for millions 3 3 What effect can coffee have on the stomach? 4 4 Can coffee trigger heartburn or GORD? 5 5 Is coffee associated with the development of gastric or duodenal ulcers? 6 6 Can coffee help gallbladder or pancreatic function? 7 7 Does coffee consumption have an impact on the lower digestive tract? 8 8 Coffee and gut microbiota — an emerging area of research 9 9 About ISIC 10 10 References 11 www.coffeeandhealth.org May 2020 1 Expert report Coffee and its effect on digestion Overview There have been a number of studies published on coffee and its effect on different areas of digestion; some reporting favourable effects, while other studies report fewer positive effects. This report provides an overview of this body of research, highlighting a number of interesting findings that have emerged to date. Digestion is the breakdown of food and drink, which occurs through the synchronised function of several organs. It is coordinated by the nervous system and a number of different hormones, and can be impacted by a number of external factors. Coffee has been suggested as a trigger for some common digestive complaints from stomach ache and heartburn, through to bowel problems. Research suggests that coffee consumption can stimulate gastric, bile and pancreatic secretions, all of which play important roles in the overall process of digestion1–6. -

THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM: Introduction and Upper GI

THE DIGESTIVE SYSTEM: Introduction and upper GI Dalay Olson Ph.D Office: Jackson Hall 3-120 Office hours: Monday 2-3pm INTRODUCTION TO GI LEARNING OBJECTIVES 3 Distinguish between the wall layers of the esophagus and those classically represented by the small intestine. ESOPHAGUS STRUCTURE UPPER THIRD ESOPHAGUS STRUCTURE LOWER TWO-THIRDS 4 Describe the voluntary and reflex components of swallowing. PHASES OF SWALLOWING Swallowing is integrated in the medulla oblongata. Voluntary Phase Pharyngeal Phase Esophageal Phase The swallowing reflex requires input from sensory afferent nerves, somatic motor nerves and autonomic nerves. VOLUNTARY PHASE The tongue pushes the bolus of food back and upwards towards the back of the mouth. Once the food touches the soft palate and the back of the mouth it triggers the swallowing reflex. This is the stimulus! PHARYNGEAL PHASE • Once the food touches the soft palate and the back of the mouth it triggers the swallowing reflex. This is the stimulus! • The medulla oblongata (control center) then initiates the swallowing reflex causing the soft palate to elevate, closing of the glottis and opening of the esophageal sphincter (response). • Once the food moves into the esophagus the sphincter closes once again. The glottis then opens again and breathing resumes. ESOPHAGEAL PHASE 1. Food moves along the esophagus by peristalsis (waves of smooth muscle contractions) • If the food gets stuck, short reflexes will continue peristalsis. • Myogenic reflex (you will learn about this later) produces contractions that move food forward. 2. As the bolus of food moves toward the stomach the lower esophageal sphincter relaxes and opens allowing the food to move into the stomach. -

The Herbivore Digestive System Buffalo Zebra

The Herbivore Digestive System Name__________________________ Buffalo Ruminant: The purpose of the digestion system is to ______________________________ _____________________________. Bacteria help because they can digest __________________, a sugar found in the cell walls of________________. Zebra Non- Ruminant: What is the name for the largest section of Organ Color Key a ruminant’s Mouth stomach? Esophagus __________ Stomach Small Intestine Cecum Large Intestine Background Information for the Teacher Two Strategies of Digestion in Hoofed Mammals Ruminant Non‐ruminant Representative species Buffalo, cows, sheep, goats, antelope, camels, Zebra, pigs, horses, asses, hippopotamus, rhinoceros giraffes, deer Does the animal Yes, regurgitation No regurgitation regurgitate its cud to Grass is better prepared for digestion, as grinding Bacteria can not completely digest cell walls as chew material again? motion forms small particles fit for bacteria. material passes quickly through, so stool is fibrous. Where in the system do At the beginning, in the rumen Near the end, in the cecum you find the bacteria This first chamber of its four‐part stomach is In this sac between the two intestines, bacteria digest that digest cellulose? large, and serves to store food between plant material, the products of which pass to the rumination and as site of digestion by bacteria. bloodstream. How would you Higher Nutrition Lower Nutrition compare the nutrition Reaps benefits of immediately absorbing the The digestive products made by the bacteria are obtained via digestion? products of bacterial digestion, such as sugars produced nearer the end of the line, after the small and vitamins, via the small intestine. intestine, the classic organ of nutrient absorption. -

The Baseline Structure of the Enteric Nervous System and Its Role in Parkinson’S Disease

life Review The Baseline Structure of the Enteric Nervous System and Its Role in Parkinson’s Disease Gianfranco Natale 1,2,* , Larisa Ryskalin 1 , Gabriele Morucci 1 , Gloria Lazzeri 1, Alessandro Frati 3,4 and Francesco Fornai 1,4 1 Department of Translational Research and New Technologies in Medicine and Surgery, University of Pisa, 56126 Pisa, Italy; [email protected] (L.R.); [email protected] (G.M.); [email protected] (G.L.); [email protected] (F.F.) 2 Museum of Human Anatomy “Filippo Civinini”, University of Pisa, 56126 Pisa, Italy 3 Neurosurgery Division, Human Neurosciences Department, Sapienza University of Rome, 00135 Rome, Italy; [email protected] 4 Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico (I.R.C.C.S.) Neuromed, 86077 Pozzilli, Italy * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The gastrointestinal (GI) tract is provided with a peculiar nervous network, known as the enteric nervous system (ENS), which is dedicated to the fine control of digestive functions. This forms a complex network, which includes several types of neurons, as well as glial cells. Despite extensive studies, a comprehensive classification of these neurons is still lacking. The complexity of ENS is magnified by a multiple control of the central nervous system, and bidirectional communication between various central nervous areas and the gut occurs. This lends substance to the complexity of the microbiota–gut–brain axis, which represents the network governing homeostasis through nervous, endocrine, immune, and metabolic pathways. The present manuscript is dedicated to Citation: Natale, G.; Ryskalin, L.; identifying various neuronal cytotypes belonging to ENS in baseline conditions. -

Mouth Esophagus Stomach Rectum and Anus Large Intestine Small

1 Liver The liver produces bile, which aids in digestion of fats through a dissolving process known as emulsification. In this process, bile secreted into the small intestine 4 combines with large drops of liquid fat to form Healthy tiny molecular-sized spheres. Within these spheres (micelles), pancreatic enzymes can break down fat (triglycerides) into free fatty acids. Pancreas Digestion The pancreas not only regulates blood glucose 2 levels through production of insulin, but it also manufactures enzymes necessary to break complex The digestive system consists of a long tube (alimen- 5 carbohydrates down into simple sugars (sucrases), tary canal) that varies in shape and purpose as it winds proteins into individual amino acids (proteases), and its way through the body from the mouth to the anus fats into free fatty acids (lipase). These enzymes are (see diagram). The size and shape of the digestive tract secreted into the small intestine. varies in each individual (e.g., age, size, gender, and disease state). The upper part of the GI tract includes the mouth, throat (pharynx), esophagus, and stomach. The lower Gallbladder part includes the small intestine, large intestine, The gallbladder stores bile produced in the liver appendix, and rectum. While not part of the alimentary 6 and releases it into the duodenum in varying canal, the liver, pancreas, and gallbladder are all organs concentrations. that are vital to healthy digestion. 3 Small Intestine Mouth Within the small intestine, millions of tiny finger-like When food enters the mouth, chewing breaks it 4 protrusions called villi, which are covered in hair-like down and mixes it with saliva, thus beginning the first 5 protrusions called microvilli, aid in absorption of of many steps in the digestive process. -

IDP Biological Systems Gastrointestinal System

IDP Biological Systems Gastrointestinal System Section Coordinator: Jerome W. Breslin, PhD, Assistant Professor of Physiology, MEB 7208, 504-568-2669, [email protected] Overall Learning Objectives 1. Characterize the important anatomical features of the GI system in relation to GI function. 2. Describe the molecular and cellular mechanisms underlying GI motility. Highlight the neural and endocrine regulatory mechanisms. Characterize the different types of GI motility in different segments of the GI tract. 3. Define the major characteristics and temporally relate the cephalic, gastric, and intestinal phases of GI tract regulation. 4. For carbohydrates, proteins, fats, vitamins, minerals, and oral drugs, differentiate the processes of ingestion, digestion, absorption, secretion, and excretion, including the location in the GI tract where each process occurs. 5. Contrast the sympathetic and parasympathetic modulation of the enteric nervous system and the effector organs of the GI tract. 6. Describe the similarities and differences in regulating gastrointestinal function by nerves, hormones, and paracrine regulators. Include receptors, proximity, and local vs. global specificity. 7. Understand the basic mechanisms underlying several common GI disorders and related treatment strategies. Learning Objectives for Specific Hours: Hour 1 – Essential Concepts: Cellular transport mechanisms and Mechanisms of Force Generation 1. Describe the composition of cell membranes and how distribution of phospholipids and proteins influence membrane permeability of ions, hydrophilic, and hydrophobic compounds. 2. Using a cell membrane as an example, define a reflection coefficient, and explain how the relative permeability of a cell to water and solutes will generate osmotic pressure. Contrast the osmotic pressure generated across a cell membrane by a solution of particles that freely cross the membrane with that of a solution with the same osmolality, but particles that cannot cross the cell membrane. -

Pathophysiology, 6Th Edition

McCance: Pathophysiology, 6th Edition Chapter 38: Structure and Function of the Digestive System Key Points – Print SUMMARY REVIEW The Gastrointestinal Tract 1. The major functions of the gastrointestinal tract are the mechanical and chemical breakdown of food and the absorption of digested nutrients. 2. The gastrointestinal tract is a hollow tube that extends from the mouth to the anus. 3. The walls of the gastrointestinal tract have several layers: mucosa, muscularis mucosae, submucosa, tunica muscularis (circular muscle and longitudinal muscle), and serosa. 4. Except for swallowing and defecation, which are controlled voluntarily, the functions of the gastrointestinal tract are controlled by extrinsic and intrinsic autonomic nerves (enteric plexus) and intestinal hormones. 5. Digestion begins in the mouth, with chewing and salivation. The digestive component of saliva is α-amylase, which initiates carbohydrate digestion. 6. The esophagus is a muscular tube that transports food from the mouth to the stomach. The tunica muscularis in the upper part of the esophagus is striated muscle, and that in the lower part is smooth muscle. 7. Swallowing is controlled by the swallowing center in the reticular formation of the brain. The two phases of swallowing are the oropharyngeal phase (voluntary swallowing) and the esophageal phase (involuntary swallowing). 8. Food is propelled through the gastrointestinal tract by peristalsis: waves of sequential relaxations and contractions of the tunica muscularis. 9. The lower esophageal sphincter opens to admit swallowed food into the stomach and then closes to prevent regurgitation of food back into the esophagus. 10. The stomach is a baglike structure that secretes digestive juices, mixes and stores food, and propels partially digested food (chyme) into the duodenum. -

Physiology of the Pancreas

LECTURE IV: Physiology of the Pancreas EDITING FILE IMPORTANT MALE SLIDES EXTRA FEMALE SLIDES LECTURER’S NOTES 1 PHYSIOLOGY OF THE PANCREAS Lecture Four OBJECTIVES ● Functional Anatomy ● Major components of pancreatic juice and their physiologic roles ● Cellular mechanisms of bicarbonate secretion ● Cellular mechanisms of enzyme secretion ● Activation of pancreatic enzymes ● Hormonal & neural regulation of pancreatic secretion ● Potentiation of the secretory response Pancreas Lying parallel to and beneath the stomach, it is a large compound gland with most of its internal structure similar to that of the salivary glands. It is composed of: Figure 4-1 Endocrine portion 1-2% Exocrine portion 95% (Made of Islets of Langerhans) (Acinar gland tissues) Secrete hormones into the blood Made of acinar & ductal cells.1 - ● Insulin (beta cells; 60%) secretes digestive enzymes, HCO3 ● Glucagon (alpha cells; 25%) and water into the duodenum . ● Somatostatin (delta cells; 10%). Figure 4-2 Figure 4-3 ● The pancreatic digestive enzymes are secreted by pancreatic acini. ● Large volumes of sodium bicarbonate solution are secreted by the small ductules and larger ducts leading from the acini. ● Pancreatic juice is secreted in response to the presence of chyme in the upper portions of the small intestine. ● Insulin and Glucagon are crucial for normal regulation of glucose, lipid, and protein metabolism. FOOTNOTES 1. Acinar cells arrange themselves like clusters of grapes, that eventually release their secretions into ducts. Collection of acinar cells is called acinus, acinus and duct constitute one exocrine gland. 2 PHYSIOLOGY OF THE PANCREAS Lecture Four Pancreatic Secretion: ● Amount ≈ 1.5 L/day in an adult human. ● The major functions of pancreatic secretion: To neutralize the acids in the duodenal chyme to optimum range 1 (pH=7.0-8.0) for activity of pancreatic enzymes. -

Study Guide Medical Terminology by Thea Liza Batan About the Author

Study Guide Medical Terminology By Thea Liza Batan About the Author Thea Liza Batan earned a Master of Science in Nursing Administration in 2007 from Xavier University in Cincinnati, Ohio. She has worked as a staff nurse, nurse instructor, and level department head. She currently works as a simulation coordinator and a free- lance writer specializing in nursing and healthcare. All terms mentioned in this text that are known to be trademarks or service marks have been appropriately capitalized. Use of a term in this text shouldn’t be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Copyright © 2017 by Penn Foster, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of the material protected by this copyright may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the copyright owner. Requests for permission to make copies of any part of the work should be mailed to Copyright Permissions, Penn Foster, 925 Oak Street, Scranton, Pennsylvania 18515. Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INSTRUCTIONS 1 READING ASSIGNMENTS 3 LESSON 1: THE FUNDAMENTALS OF MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY 5 LESSON 2: DIAGNOSIS, INTERVENTION, AND HUMAN BODY TERMS 28 LESSON 3: MUSCULOSKELETAL, CIRCULATORY, AND RESPIRATORY SYSTEM TERMS 44 LESSON 4: DIGESTIVE, URINARY, AND REPRODUCTIVE SYSTEM TERMS 69 LESSON 5: INTEGUMENTARY, NERVOUS, AND ENDOCRINE S YSTEM TERMS 96 SELF-CHECK ANSWERS 134 © PENN FOSTER, INC. 2017 MEDICAL TERMINOLOGY PAGE III Contents INSTRUCTIONS INTRODUCTION Welcome to your course on medical terminology. You’re taking this course because you’re most likely interested in pursuing a health and science career, which entails proficiencyincommunicatingwithhealthcareprofessionalssuchasphysicians,nurses, or dentists. -

The Role of Lactic Acid in Gastric Digestion

[Reprinted from The Medical News, December 30, 1893.] THE ROLE OF LACTIC ACID IN GASTRIC DIGESTIOA ALLEN A. JONES, M.D., CLINICAL INSTRUCTOR IN MEDICINE AND INSTRUCTOR IN PRACTICE, MEDICAL DEPARTMENT, UNIVERSITY OF BUFFALO. Lactic acid is present in the stomach under nor- mal conditions from thirty to forty minutes after a test-meal composed of a roll and water or of chopped lean beef, dry bread, and water. At the expiration of that time lactic acid should entirely disappear from the stomach-contentsand free hydro- chloric acid alone should prevail. During the first thirty or forty minutes after meals the digestion of starches and albuminoids progresses quite rapidly, as may be proved by finding the middle-products and end-products of gastric digestion present, so that the presence of free lactic acid does not pro- hibit digestion. As soon as food enters the healthy stomach the secretion of hydrochloric acid is excited and it increases in amount until the production of lactic acid is checked. The exact origin of lactic acid in the healthy stomach is still a matter of debate. It may arise wholly from fermentation, or from the combination of some food-product with a secretion 1 Read before the Buffalo Academy of Medicine, November x 4) 1893. 2 from the gastric glandules, or from the gastric mucosa as a distinct secretion, although electric stimulation of the gastric glandules excites the se- cretion of hydrochloric acid and not of lactic acid. I think it arises largely from fermentation of the food, as its amount is usually proportionate to the amount of starchy, saccharine, and milk foods taken. -

Gastrointestinal Motility Physiology

GASTROINTESTINAL MOTILITY PHYSIOLOGY JAYA PUNATI, MD DIRECTOR, PEDIATRIC GASTROINTESTINAL, NEUROMUSCULAR AND MOTILITY DISORDERS PROGRAM DIVISION OF PEDIATRIC GASTROENTEROLOGY AND NUTRITION, CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL LOS ANGELES VRINDA BHARDWAJ, MD DIVISION OF PEDIATRIC GASTROENTEROLOGY AND NUTRITION CHILDREN’S HOSPITAL LOS ANGELES EDITED BY: CHRISTINE WAASDORP HURTADO, MD REVIEWED BY: JOSEPH CROFFIE, MD, MPH NASPGHAN PHYSIOLOGY EDUCATION SERIES SERIES EDITORS: CHRISTINE WAASDORP HURTADO, MD, MSCS, FAAP [email protected] DANIEL KAMIN, MD [email protected] CASE STUDY 1 • 14 year old female • With no significant past medical history • Presents with persistent vomiting and 20 lbs weight loss x 3 months • Initially emesis was intermittent, occurred before bedtime or soon there after, 2-3 hrs after a meal • Now occurring immediately or up to 30 minutes after a meal • Emesis consists of undigested food and is nonbloody and nonbilious • Associated with heartburn and chest discomfort 3 CASE STUDY 1 • Initial screening blood work was unremarkable • A trial of acid blockade was started with improvement in heartburn only • Antiemetic therapy with ondansetron showed no improvement • Upper endoscopy on acid blockade was normal 4 CASE STUDY 1 Differential for functional/motility disorders: • Esophageal disorders: – Achalasia – Gastroesophageal Reflux – Other esophageal dysmotility disorders • Gastric disorders: – Gastroparesis – Rumination syndrome – Gastric outlet obstruction : pyloric stricture, pyloric stenosis • -

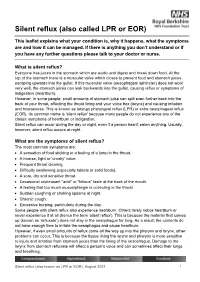

Silent Reflux (Also Called LPR Or EOR)

Silent reflux (also called LPR or EOR) This leaflet explains what your condition is, why it happens, what the symptoms are and how it can be managed. If there is anything you don’t understand or if you have any further questions please talk to your doctor or nurse. What is silent reflux? Everyone has juices in the stomach which are acidic and digest and break down food. At the top of the stomach there is a muscular valve which closes to prevent food and stomach juices escaping upwards into the gullet. If this muscular valve (oesophageal sphincter) does not work very well, the stomach juices can leak backwards into the gullet, causing reflux or symptoms of indigestion (heartburn). However, in some people, small amounts of stomach juice can spill even further back into the back of your throat, affecting the throat lining and your voice box (larynx) and causing irritation and hoarseness. This is known as laryngo pharyngeal reflux (LPR) or extra oesophageal reflux (EOR). Its common name is 'silent reflux' because many people do not experience any of the classic symptoms of heartburn or indigestion. Silent reflux can occur during the day or night, even if a person hasn't eaten anything. Usually, however, silent reflux occurs at night. What are the symptoms of silent reflux? The most common symptoms are: • A sensation of food sticking or a feeling of a lump in the throat. • A hoarse, tight or 'croaky' voice. • Frequent throat clearing. • Difficulty swallowing (especially tablets or solid foods). • A sore, dry and sensitive throat. • Occasional unpleasant "acid" or "bilious" taste at the back of the mouth.