The Law in Shakespeare

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Download Hamlet: the Texts of 1603 and 1623 Ebook

HAMLET: THE TEXTS OF 1603 AND 1623 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK William Shakespeare,Ann Thompson,Neil Taylor | 384 pages | 31 May 2007 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781904271802 | English | London, United Kingdom Hamlet: The Texts of 1603 and 1623 PDF Book The New Cambridge, prepared by Philip Edwards, also conflated while using the Folio as its base text. It looks like you are located in Australia or New Zealand Close. For your intent In going back to school in Wittenberg, It is most retrograde to our desire, And we beseech you bend you to remain Here in the cheer and comfort of our eye, Our chiefest courtier, cousin, and our son. An innnovative and stimulating contribution. On approval, you will either be sent the print copy of the book, or you will receive a further email containing the link to allow you to download your eBook. This wonderful ternion gives the serious students of Hamlet everything they need to delve deeply into the Dane. You can unsubscribe from newsletters at any time by clicking the unsubscribe link in any newsletter. A beautiful, unmarked, tight copy. By using our website you consent to all cookies in accordance with our Cookie Policy. Password Forgot Password? What says Polonius? While Jonson and other writers labored over their plays, Shakespeare seems to have had the ability to turn out work of exceptionally high caliber at an amazing speed. Gerald D. May show signs of minor shelf wear and contain limited notes and highlighting. Who's there? But, look, the morn in russet mantle clad, Walks o'er the dew of yon high eastern hill. -

The Tragedy of Hamlet

THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET THE WORKS OF SHAKESPEARE THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET EDITED BY EDWARD DOWDEN n METHUEN AND CO. 36 ESSEX STREET: STRAND LONDON 1899 9 5 7 7 95 —— CONTENTS PAGE Introduction ix The Tragedy of Hamlet i Appendix I. The "Travelling" of the Players. 229 Appendix II.— Some Passages from the Quarto of 1603 231 Appendix III. Addenda 235 INTRODUCTION This edition of Hamlet aims in the first place at giving a trustworthy text. Secondly, it attempts to exhibit the variations from that text which are found in the primary sources—the Quarto of 1604 and the Folio of 1623 — in so far as those variations are of importance towards the ascertainment of the text. Every variation is not recorded, but I have chosen to err on the side of excess rather than on that of defect. Readings from the Quarto of 1603 are occa- sionally given, and also from the later Quartos and Folios, but to record such readings is not a part of the design of this edition. 1 The letter Q means Quarto 604 ; F means Folio 1623. The dates of the later Quartos are as follows: —Q 3, 1605 161 1 undated 6, For ; Q 4, ; Q 5, ; Q 1637. my few references to these later Quartos I have trusted the Cambridge Shakespeare and Furness's edition of Hamlet. Thirdly, it gives explanatory notes. Here it is inevitable that my task should in the main be that of selection and condensation. But, gleaning after the gleaners, I have perhaps brought together a slender sheaf. -

Unbound, Volume 9

UNBOUND A Review of Legal History and Rare Books Journal of the Legal History and Rare Books Special Interest Section of the American Association of Law Libraries Volume 9 2016 UNBOUND A Review of Legal History and Rare Books Unbound: A Review of Legal History and Rare Books (previously published as Unbound: An Annual Review of Legal History and Rare Books) is published by the Legal History and Rare Books Special Interest Section of the American Association of Law Li- braries. Articles on legal history and rare books are both welcomed and encouraged. Contributors need not be members of the Legal His- tory and Rare Books Special Interest Section of the American As- sociation of Law Libraries. Citation should follow any commonly-used citation guide. Cover Illustration: This depiction of an American Bison, en- graved by David Humphreys, was first published in Hughes Ken- tucky Reports (1803). It was adopted as the symbol of the Legal History and Rare Books Special Interest Section in 2007. BOARD OF EDITORS Mark Podvia, Editor-in-Chief Associate University Librarian West Virginia University College of Law Library P.O. Box 6130 Morgantown, WV 26506 Phone: (304)293-6786 Email: [email protected] Noelle M. Sinclair, Executive Editor Head of Special Collections The University of Iowa College of Law 328 Boyd Law Building Iowa City, IA 52242 Phone (319)335-9002 [email protected] Kurt X. Metzmeier, Articles Editor Associate Director University of Louisville Law Library Belknap Campus, 2301 S. Third Louisville, KY 40292 Phone (502)852-6082 [email protected] Joel Fishman, Ph.D., Book Review Editor Assistant Director for Lawyer Services Duquesne University Center for Legal Information/Allegheny Co. -

Night Papers V on the Labyrinthitis Stuff By: —Joanna Fiduccia State of Curating Aaron Wrinkle • Brad Phillips • I

LOS ANGELES | 2014 NIGHT GALLERY | 2276 E . 16TH ST. NIGHT PAPERS V ON THE LABYRINTHITIS STUFF BY: —JOANNA FIDUCCIA STATE OF CURATING AARON WRINKLE • BRAD PHILLIPS • I. RADIO HOUR M. CAY CASTAGNETTO • TODAY P6. JPW3 • coutez... Faites silence. Robert Desnos bids you listen — BOB NICKAS & ALLANA DEL RAY SAMANTHA COHEN • and be still, for the evening of Fantômas is beginning. It ZACH HARRIS • is November 3, 1933, and your rhapsode is as far away & MORE Eand near at hand as any voice on the radio — in this case, Radio Paris, which has marshaled its resources to present Desnos’s I MAY BE CRAZY BUT I’M NOT STUPID “Complainte de Fantômas.” A lyrical account of the crimes of the — JOHNNIE JUNGLEGUTS vagabond Fantômas, scheduled to coincide with the release of a P12. new episode in the popular series by Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre, Desnos’s poem is an advertisement with an outsize avant-garde pedigree (Kurt Weill composed the background music; Antonin Artaud directed and read the role of Fantômas) that would induct him into minor radio personality fame. The poet had been initiated into the blind art some three years earlier by a young entrepreneur and radio enthusiast by the name of Paul Deharme. Deharme, perhaps more than any of the other lapsed Surrealists that would follow in his path, was devoted to the radio’s novel artistic possibilities. In March 1928, he published “Proposition pour un art radiophonique,” a strangely matter-of-fact manifesto on the potentials of this new “wireless art,” combining a semi-digested Freud with a list of techniques to produce visions in the listener — the use of the present indicative, background music, adherence to chronology, and so forth. -

Making Shakespeare Accessible to the High School Student: a Study of Language and Relationships in Hamlet and the Taming of the Shrew

Making Shakespeare Accessible to the High School Student: A Study of Language and Relationships in Hamlet and The Taming of the Shrew Virginia Kay Jones INTRODUCTION Having taught for over thirty years at an inner city high school, I have tried not only to shape my curriculum to my students‘ needs but also to make the study of British literature relevant to my students‘ lives. The teaching of Shakespeare is always a challenge. I have taught Romeo and Juliet, Julius Caesar, Macbeth, The Taming of the Shrew, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Hamlet—all with varying degrees of success. For the past few years, Hamlet has been my focal point for the spring semester of senior English. Although my students enjoy the play—often stating that it is the first Shakespearean play that they have liked—I feel that I can do more than what I am doing. By just reading and discussing a play, a student cannot appreciate the essence of the work. My students love language. They can improvise rap and create beautiful poetry with little prompting. However, they are afraid to tackle Shakespeare. I intend to design a unit that will make the study of Shakespeare more accessible to my students by helping them ―come to terms‖ with the language. My students also love to act, so I want to teach Shakespeare with a more performance-based approach. Additionally, I want to expose my students to Shakespearean comedy as well as tragedy. A unit designed around the theme of relationships (male-female, sibling, and parent-child) is the thread to connect Hamlet and The Taming of the Shrew and make them more relevant to today‘s students. -

Hamlet (The New Cambridge Shakespeare, Philip Edwards Ed., 2E, 2003)

Hamlet Prince of Denmark Edited by Philip Edwards An international team of scholars offers: . modernized, easily accessible texts • ample commentary and introductions . attention to the theatrical qualities of each play and its stage history . informative illustrations Hamlet Philip Edwards aims to bring the reader, playgoer and director of Hamlet into the closest possible contact with Shakespeare's most famous and most perplexing play. He concentrates on essentials, dealing succinctly with the huge volume of commentary and controversy which the play has provoked and offering a way forward which enables us once again to recognise its full tragic energy. The introduction and commentary reveal an author with a lively awareness of the importance of perceiving the play as a theatrical document, one which comes to life, which is completed only in performance.' Review of English Studies For this updated edition, Robert Hapgood Cover design by Paul Oldman, based has added a new section on prevailing on a draining by David Hockney, critical and performance approaches to reproduced by permission of tlie Hamlet. He discusses recent film and stage performances, actors of the Hamlet role as well as directors of the play; his account of new scholarship stresses the role of remembering and forgetting in the play, and the impact of feminist and performance studies. CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS www.cambridge.org THE NEW CAMBRIDGE SHAKESPEARE GENERAL EDITOR Brian Gibbons, University of Munster ASSOCIATE GENERAL EDITOR A. R. Braunmuller, University of California, Los Angeles From the publication of the first volumes in 1984 the General Editor of the New Cambridge Shakespeare was Philip Brockbank and the Associate General Editors were Brian Gibbons and Robin Hood. -

Dispensa I Anno Villa

1 TOM McALINDON What is a Shakespearean tragedy? ‘Double, double toil and trouble . .’ (Mac. 4.1.10) I An eminent Shakespearean scholar famously remarked that there is no such thing as Shakespearean Tragedy: there are only Shakespearean tragedies. Attempts (he added) to find a formula which fits every one of Shakespeare’s tragedies and distinguishes them collectively from those of other dramatists invariably meet with little success. Yet when challenging one such attempt he noted its failure to observe what he termed ‘an essential part of the [Shakespearean] tragic pattern’;1 which would seem to imply that these plays do have some shared characteristics peculiar to them. Nevertheless, objections to comprehensive definitions of ‘Shakespearean Tragedy’ are well founded. Such definitions tend to ignore the uniqueness of each play and the way it has been structured and styled to fit the partic- ular source-narrative. More generally, they can obscure the fact that what distinguishes Shakespeare’s tragedies from everyone else’s and prompts us to consider them together are not so much common denominators but rather the power of Shakespeare’s language, his insight into character, and his dramaturgical inventiveness.2 Uneasiness with definitions of Shakespearean tragedy is of a kind with the uneasiness generated by definitions of tragedy itself; these often give a static impression of the genre and incline towards prescriptiveness, ignoring the fact that ‘genres are in a constant state of transmutation’.3 There is, how- ever, a simple argument to be made in defence of genre criticism, namely that full understanding and appreciation of any piece of literature requires knowledge of its contexts, literary as well as intellectual and socio-political: in its relation to the author and his work, context informs, assists, stimulates, provokes. -

Ell 1E5 570 ' CS 20 5 4,96;

. MC0111117 VESUI17 Ell 1E5 570 ' CS 20 5 4,96; AUTHOR McLean, Ardrew M. TITLE . ,A,Shakespeare: Annotated BibliographiesendAeaiaGuide 1 47 for Teachers. .. INSTIT.UTION. NIttional Council of T.eachers of English, Urbana, ..Ill. .PUB DATE- 80 , NOTE. 282p. AVAILABLe FROM Nationkl Coun dil of Teachers,of Englishc 1111 anyon pa., Urbana, II 61.801 (Stock No. 43776, $8.50 member, . , $9.50 nor-memberl' , EDRS PRICE i MF011PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Biblioal7aphies: *Audiovisual Aids;'*Dramt; +English Irstruction: Higher Education; 4 *InstrUctioiral Materials: Literary Criticism; Literature: SecondaryPd uc a t i on . IDENTIFIERS *Shakespeare (Williaml 1 ABSTRACT The purpose of this annotated b'iblibigraphy,is to identify. resou'rces fjor the variety of approaches tliat teachers of courses in Shakespeare might use. Entries in the first part of the book lear with teaching Shakespeare. in secondary schools and in college, teaching Shakespeare as- ..nerf crmance,- and teaching , Shakespeare with other authora. Entries in the second part deal with criticism of Shakespearear films. Discussions of the filming of Shakespeare and of teachi1g Shakespeare on, film are followed by discu'ssions 'of 26 fgature films and the,n by entries dealing with Shakespearean perforrances on televiqion: The third 'pax't of the book constituAsa glade to avAilable media resources for tlip classroom. Ittries are arranged in three categories: Shakespeare's life'and' iimes, Shakespeare's theater, and Shakespeare 's plam. Each category, lists film strips, films, audi o-ca ssette tapes, and transparencies. The.geteral format of these entries gives the title, .number of parts, .grade level, number of frames .nr running time; whether color or bie ack and white, producer, year' of .prOduction, distributor, ut,itles of parts',4brief description of cOntent, and reviews.A direCtory of producers, distributors, ard rental sources is .alst provided in the 10 book.(FL)- 4 to P . -

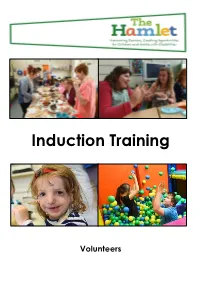

Induction Training

Induction Training Volunteers Our Vision To provide an environment for children and adults that overcomes the challenges of their disabilities and complex health needs and provides each with opportunities to unlock their potential. Our Beliefs Our belief is that everyone at The Hamlet: • should be happy and safe, • is unique and valued, • can explore choice and opportunities, • is encouraged to unlock their potential, • can communicate in their own way, • and is part of the wider community. What we do We believe people with disabilities and complex health needs deserve to be valued for who they are. This means being given the chance to explore choice, communicate, unlock potential and take new opportunities. We work with babies to young adults at 29 years. This allows us, often over many years, to gain both trust and a real insight as to how best to create a person-centred plan to support each individual and their family. What makes us different? • We go the extra mile • We place an emphasis on fun • We choose vibrant and innovative approaches which embrace technology • We create a family feel The Hamlet Children’s Centre Johnson Place provides a range of activities for children and young people with learning disabilities and complex health needs, some who may be very poorly. Play- schemes are planned with a range of activities and experiences which include trips out, sensory exploration, sports, cooking, music and art. The Hamlet Adult’s Centre Ella Road provides a range of activities for young adults/members with learning disabilities and complex health needs. We offer a varied timetable which is planned with a range of activities and experiences which include trips out, sensory exploration, sports, cooking, music and art, which changes on a termly basis, reflecting the needs and interests of our students. -

Neil Forsyth

SHAKET SPEARE H E ILLUMAGIC, DREAMS, ANSID THEON SUPERNATURALIS ON FITLM NEIL FORSYTH OhiO University Press • Athens CONTENTS A cknowledgments vii Introduction. From Stage to Screen 1 P ART ONE: FILM LANGUAGE 1. Silent Ghosts, Speaking Ghosts: Movies about Movies 13 2. Méliès and the Pioneers 19 P WART T O: SHAKESPEARE FILMS 3. “Stay, Illusion” 31 4. Supernatural Comedies A Midsummer Night’s Dream and The Tempest 38 5. “The Most Unfortunate Major Film Ever Produced” Shakespeare and the Talkies 62 6. Ghosts and Courts The Openings of Hamlet 80 7. Macbeth and the Supernatural 130 Conclusion. A New Hybrid: Taymor’s Dream 162 Notes 167 Bibliography 203 Index 217 v INTRODUCTION From Stage to Screen “IF SHAKESPEARE WE ER alive today, he would be writing screenplays.” This remark, or something like it, has often been attributed to Sir Laurence Olivier. Barbara Hodgdon says that her colleague Jim Burn- stein credits his teacher, Russell Fraser, but she allows that Olivier was probably the first to remark that if Shakespeare were around now he would be writing new television comedies or soap opera parts for aging actors. Certainly by the late 1960s or early 1970s, the idea that Shake- speare wrote “cinematically” was circulating in academic culture, spawn- ing courses titled Shakespeare on Film or (eventually) Shakespeare and Film.1 Julie Taymor’s film ofTitus Andronicus opened in December 1999. In the first sentence of hisNew York Times review, Jonathan Bate offered a slightly different version of the remark but without attribution: “If William Shakespeare were alive today, he would be writing and direct- ing movies.”2 Indeed, Shakespeare has been called, bizarrely, the most popular screenwriter in Hollywood.3 There are not only film or televi- sion versions of all of his works but also multiple versions of many. -

Hamlet Prince of Denmark 1St Edition Ebook Free Download

HAMLET PRINCE OF DENMARK 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK William Shakespeare | 9780743482783 | | | | | Hamlet Prince of Denmark 1st edition PDF Book Provenance: The A. Hirrel, Michael J. Newark: University of Delaware Press. Remains quite well-preserved overall: tight, bright, clean and strong. Saxo Grammaticus Two young women whose stories intertwine in dangerous ways as they discover that their past holds the key Jeff Dolven Editor ,. Previous theories and critical observations are also analysed for a proper assessment of the play. John Barrymore 's long-running performance in New York, directed by Thomas Hopkins, "broke new ground in its Freudian approach to character", in keeping with the post-World War I rebellion against everything Victorian. Seller Image. Gilbert, W. Hamlet jokes with Claudius about where he has hidden Polonius's body, and the king, fearing for his life, sends Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to accompany Hamlet to England with a sealed letter to the English king requesting that Hamlet be executed immediately. Hamlet feigns madness and subtly insults Polonius all the while. Early drafts of the play date back to , making it a nearly year old spectacle that continues to delight, confound, capture, and engage or enrage? Law, Jude 2 October Oxford English Dictionary 3rd ed. Clark, for J. Oxford Guides. A fine, clean, neat soft cover with light shelf wear, gently read, binding tight, paper cream white. Burian, Jarka []. Hamlet Kindle Edition. Linguist George T. Our BookSleuth is specially designed for you. It is nothing but a bunch of quotations strung together. Ian Mckellen: An Unofficial Biography. Vickers, Brian , ed. Norwood, PA: Norwood Editions. -

Stages of Emotion: Shakespeare, Performance, and Affect in Modern Anglo-American Film and Theatre

Stages of Emotion: Shakespeare, Performance, and Affect in Modern Anglo-American Film and Theatre Emily Lang Madison Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2020 © 2019 Emily Lang Madison All Rights Reserved Abstract Stages of Emotion: Shakespeare, Performance, and Affect in Modern Anglo-American Film and Theatre Emily Lang Madison This dissertation makes a case for the Shakespearean stage in the modern Anglo- American tradition as a distinctive laboratory for producing and navigating theories of emotion. The dissertation brings together Shakespeare performance studies and the newer fields of the history of emotions and cultural emotion studies, arguing that Shakespeare’s enduring status as the playwright of human emotion makes the plays in performance critical sites of discourse about human emotion. More specifically, the dissertation charts how, since the late nineteenth century, Shakespeare performance has been implicated in an effort to understand emotion as it defines and relates to the “human” subject. The advent of scientific materialism and Darwinism involved a dethroning of emotion and its expression as a specially endowed human faculty, best evidenced by Charles Darwin’s 1871 The Expression of Emotion in Man and Animals. Shakespeare’s poetic, formal expression of the passions was seen as proof of this faculty, and nowhere better exemplified than in the tragedies and in the passionate displays of the great tragic heroes. The controversy surrounding the tragic roles of the famous Victorian actor-manager Henry Irving illustrates how the embodied, human medium of the Shakespearean stage served as valuable leverage in contemporary debates about emotion.