Problems and Personalities of the Civil Service Reform in the Administration of Benjamin Harrison

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New—England Transcendentalism

FRENCH PHILOSOPHERS AND NEW—ENGLAND TRAN SCENDENTALISM FRENCH PHILOSOPHERS AND NEW—ENGLAND TRANSCENDENTALISM BY WALTER L. LEIGHTON H A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LITERATURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA Huihetg’itp of Eirginia CHARLOTTESVILLE, VIRGINIA 1908 To C. W. K. WHO HAS GIVEN ME BOTH THE ENCOURAGEMENT AND OPPOR'I‘UNIT‘I." FOIL THE WRITING OF THIS THESIS . PREFACE HE writings of the Transcendentalists of New England have been from youth of especial interest to me. An investi- gation of the phenomena of New-England Transcendentalism was instigated by a reading of the chapter on 'l‘ranscendentalism in Professor Barrett Wendell’s Literary History of America. The idea of making a specialty of the French influence in its relation to New-England Transcendentalism as a subject for a doctorate thesis was intimated to me by Professor LeB. R. Briggs, Dean of the Harvard University faculty. Thanks for assistance in the course of actually drawing up the dissertation are due— first, to Dr. Albert Lefevre, professor of philosophy at the University of Virginia, for valuable suggestions concerning the definition of Transcendentalism ; next, to Dr. It. H. Wilson and adjunct-professor Dr. E. P. Dargan, of the depart— ment of Romance Languages at the University of Virginia, for kind help in the work of revision and correction, and, finally, to Dr. Charles W. Kent, professor at the head of the department of English at the University of Virginia, for general supervision of - my work on the thesis. In the work of compiling and writing the thesis I have been _ swayed by two motives: first, the purpose to gather by careful research and investigation certain definite facts concerning the French philosophers and the Transcendental movement in New England; and, secondly, the desire to set forth the information amassed in a cursory and readable style. -

Election Division Presidential Electors Faqs and Roster of Electors, 1816

Election Division Presidential Electors FAQ Q1: How many presidential electors does Indiana have? What determines this number? Indiana currently has 11 presidential electors. Article 2, Section 1, Clause 2 of the Constitution of the United States provides that each state shall appoint a number of electors equal to the number of Senators or Representatives to which the state is entitled in Congress. Since Indiana has currently has 9 U.S. Representatives and 2 U.S. Senators, the state is entitled to 11 electors. Q2: What are the requirements to serve as a presidential elector in Indiana? The requirements are set forth in the Constitution of the United States. Article 2, Section 1, Clause 2 provides that "no Senator or Representative, or person holding an Office of Trust or Profit under the United States, shall be appointed an Elector." Section 3 of the Fourteenth Amendment also states that "No person shall be... elector of President or Vice-President... who, having previously taken an oath... to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. Congress may be a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability." These requirements are included in state law at Indiana Code 3-8-1-6(b). Q3: How does a person become a candidate to be chosen as a presidential elector in Indiana? Three political parties (Democratic, Libertarian, and Republican) have their presidential and vice- presidential candidates placed on Indiana ballots after their party's national convention. -

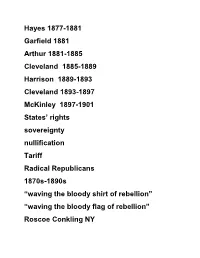

List for 202 First Exam

Hayes 1877-1881 Garfield 1881 Arthur 1881-1885 Cleveland 1885-1889 Harrison 1889-1893 Cleveland 1893-1897 McKinley 1897-1901 States’ rights sovereignty nullification Tariff Radical Republicans 1870s-1890s “waving the bloody shirt of rebellion” “waving the bloody flag of rebellion” Roscoe Conkling NY James G. Blaine Maine “Millionnaires’ Club” “the Railroad Lobby” 1. Conservative Rep party in control 2. Economy fluctuates a. Poor economy, prosperity, depression b. 1873 1893 1907 1929 c. Significant technological advances 3. Significant social changes 1876 Disputed Election of 1876 Rep- Rutherford B. Hayes Ohio Dem-Samuel Tilden NY To win 185 Tilden 184 + 1 Hayes 165 + 20 Fl SC La Oreg January 1877 Electoral Commission of 15 5 H, 5S, 5SC 7 R, 7 D, 1LR 8 to 7 Compromise of 1877 1. End reconstruction April 30, 1877 2. Appt s. Dem. Cab David Key PG 3. Support funds for internal improvements in the South Hayes 1877-1881 “ole 8 and 7 Hayes” “His Fraudulency” Carl Schurz Wm Everts Civil Service Reform Chester A. Arthur Great Strike of 1877 Resumption Act 1875 specie Bland Allison Silver Purchase Act 1878 16:1 $2-4 million/mo Silver certificates 1880 James G. Blaine Blaine Halfbreeds Rep James A Garfield Ohio Chester A. Arthur Roscoe Conkling Conkling Stalwarts Grant Dem Winfield Scott Hancock PA Greenback Party James B. Weaver Iowa Battle of the 3 Generals 1881 Arthur Pendleton Civil Service Act 1883 Chicago and Boston 1884 Election Rep. Blaine of Maine Mugwumps Dem. Grover Cleveland NY “Rum, Romanism and Rebellion” 1885-1889 Character Union Veterans Grand Army of the Republic GAR LQC Lamar S of Interior 1862 union pension 1887 Dependent Pension Bill Interstate Commerce Act 1887 ICC Pooling, rebates, drawbacks Prohibit discrimination John D. -

The Vice Presidential Bust Collection Brochure, S

Henry Wilson Garfield. Although his early political success had design for the American buffalo nickel. More than (1812–1875) ⓲ been through the machine politics of New York, 25 years after sculpting the Roosevelt bust, Fraser Daniel Chester French, Arthur surprised critics by fighting political created the marble bust of Vice President John 1886 corruption. He supported the first civil service Nance Garner for the Senate collection. THE Henry Wilson reform, and his administration was marked by epitomized the honesty and efficiency. Because he refused to Charles G. Dawes American Dream. engage in partisan politics, party regulars did not (1865–1951) VICE PRESIDENTIAL Born to a destitute nominate him in 1884. Jo Davidson, 1930 family, at age 21 he Prior to World War I, BUST COLLECTION Sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens originally walked to a nearby Charles Dawes was a declined to create Arthur’s official vice presidential town and began a lawyer, banker, and bust, citing his own schedule and the low business as a cobbler. Wilson soon embarked on politician in his native commission the Senate offered. Eventually he a career in politics, and worked his way from the Ohio. During the war, reconsidered, and delivered the finished work in Massachusetts legislature to the U.S. Senate. In a he became a brigadier politically turbulent era, he shifted political parties 1892. One of America’s best known sculptors, Saint-Gaudens also created the statue of Abraham general and afterwards several times, but maintained a consistent stand headed the Allied against slavery throughout his career. Wilson was Lincoln in Chicago’s Lincoln Park and the design reparations commission. -

Fascinating Facts About the Founding Fathers

The Founding Fathers: Fascinating Facts (Continued) Fascinating Facts About The Founding Fathers Once Gouverneur Morris was offered a bet of one Thomas Jefferson has been described as a(n): dinner if he would approach George Washington, agriculturalist, anthropologist, architect, astronomer, slap him on the back and give him a friendly greet- bibliophile, botanist, classicist, diplomat, educator, ing. He wanted to show people how “close” he ethnologist, farmer, geographer, gourmet, horseman, was to the “chief.” Morris carried out the bet, but horticulturist, inventor, lawyer, lexicographer, linguist, later admitted that after seeing the cold stare from mathematician, meteorologist, musician, naturalist, Washington, he wouldn’t do it again for a thousand numismatist, paleontologist, philosopher, political dinners! philosopher, scientist, statesman, violinist, writer. ___________________ He was also fluent in Greek, Latin, French, Spanish, Italian, and German! George Washington was born on February 11, ___________________ 1732, but in 1751 Great Britain changed from the Julian to the Gregorian calendar. An act of Parlia- Upon graduating from Harvard, John Adams became ment added eleven days to make the adjustment a grammar school teacher. “My little school, like complete and in 1752 Washington celebrated his the great world, is made up of Kings, politicians, birthday on February 22! divines, fops, buffoons, fiddlers, fools, coxcombs, ___________________ sycophants, chimney sweeps, and every other character I see in the world. I would rather sit in Of the Founding Fathers who became president, school and consider which of my pupils will turn out only George Washington did not go to college. John be a hero, and which a rake, which a philosopher Adams graduated from Harvard, James Madison and which a parasite, than to have an income of a graduated from Princeton, and Thomas Jefferson thousand pounds a year.” attended the College of William and Mary. -

To the William Howard Taft Papers. Volume 1

THE L I 13 R A R Y 0 F CO 0.: G R 1 ~ ~ ~ • P R I ~ ~ I I) I ~ \J T ~' PAP E R ~ J N 1) E X ~ E R IE S INDEX TO THE William Howard Taft Papers LIBRARY OF CONGRESS • PRESIDENTS' PAPERS INDEX SERIES INDEX TO THE William Ho-ward Taft Papers VOLUME 1 INTRODUCTION AND PRESIDENTIAL PERIOD SUBJECT TITLES MANUSCRIPT DIVISION • REFERENCE DEPARTMENT LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON : 1972 Library of Congress 'Cataloging in Publication Data United States. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division. Index to the William Howard Taft papers. (Its Presidents' papers index series) 1. Taft, William Howard, Pres. U.S., 1857-1930. Manuscripts-Indexes. I. Title. II. Series. Z6616.T18U6 016.97391'2'0924 70-608096 ISBN 0-8444-0028-9 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $24 per set. Sold in'sets only. Stock Number 3003-0010 Preface THIS INDEX to the William Howard Taft Papers is a direct result of the wish of the Congress and the President, as expressed by Public Law 85-147 approved August 16, 1957, and amended by Public Laws 87-263 approved September 21, 1961, and 88-299 approved April 27, 1964, to arrange, index, and microfilm the papers of the Presidents in the Library of Congress in order "to preserve their contents against destruction by war or other calamity," to make the Presidential Papers more "readily available for study and research," and to inspire informed patriotism. Presidents whose papers are in the Library are: George Washington James K. -

A University Microfilms International

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

The President Also Had to Consider the Proper Role of an Ex * President

************************************~ * * * * 0 DB P H0 F E8 8 0 B, * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * The little-known * * story of how * a President of the * United States, Beniamin Harrison, helped launch Stanford law School. ************************************* * * * T H E PRESIDENT * * * * * * * * * * * * By Howard Bromberg, J.D. * * * TANFORD'S first professor of law was a former President of the United * States. This is a distinction that no other school can claim. On March 2, 1893, * L-41.,_, with two days remaining in his administration, President Benjamin Harrison * * accepted an appointment as Non-Resident Professor of Constitutional Law at * Stanford University. * Harrison's decision was a triumph for the fledgling western university and its * * founder, Leland Stanford, who had personally recruited the chief of state. It also * provided a tremendous boost to the nascent Law Department, which had suffered * months of frustration and disappointment. * David Starr Jordan, Stanford University's first president, had been planning a law * * program since the University opened in 1891. He would model it on the innovative * approach to legal education proposed by Woodrow Wilson, Jurisprudence Profes- * sor at Princeton. Law would be taught simultaneously with the social sciences; no * * one would be admitted to graduate legal studies who was not already a college * graduate; and the department would be thoroughly integrated with the life and * * ************************************** ************************************* * § during Harrison's four difficult years * El in the White House. ~ In 1891, Sena tor Stanford helped ~ arrange a presidential cross-country * train tour, during which Harrison * visited and was impressed by the university campus still under con * struction. When Harrison was * defeated by Grover Cleveland in the 1892 election, it occurred to Senator * Stanford to invite his friend-who * had been one of the nation's leading lawyers before entering the Senate * to join the as-yet empty Stanford law * faculty. -

The United States Secret Service Created Four Flower- Ella and Said “Little Covered Arches That Girl, There Lies a Great and Good Man

• • “Garfield Obsequies, Sept. 26, 1881” Ella L. Grant Wilson (1854– 1939) was a Clevelander who lived through the building of the city. She was ten years old when President Lincoln’s coffin stopped in Public Square in 1965 and Ella was lifted by Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase to see inside. When James A. Garfield was assassinated in 1881, she was a successful florist and she was determined to be part of the decorating The Secret Service today can always be seen protecting the President and his family. President committee for the Eisenhower in this 1955 photo has agents walking with his car. (nps.gov) President’s funeral in Salmon P. Chase Cleveland. Mrs. Wilson lifted up the young The United States Secret Service created four flower- Ella and said “Little covered arches that girl, there lies a great and good man. Never From protecting U.S. Currency to protecting U.S. Presidents crossed Superior and forget him.” Ontario Streets. Her The United States Secret Service, a It took three presidential (Famous Old Euclid arches showcased division of the Treasury Department, assassinations – Lincoln, Garfield, and Avenue) Garfield’s life in still performs the mission it was McKinley – before formal protection of flowers and were 18 ft. high. While putting assigned during the Civil War, tracking the President of the United States was up her arches, she was kicked out of the counterfeit money, checks, bonds, and codified by law. Notably, this was nearly Square for not having a badge giving her other financial instruments, including six years after the death of President access to the funeral preparations. -

Uniting Mugwumps and the Masses: the Role of Puck in Gilded Age Politics, 1880-1884

Uniting Mugwumps and the Masses: The Role of Puck in Gilded Age Politics, 1880-1884 Daniel Henry Backer McLean, Virginia B.A., University of Notre Dame, 1994 A Thesis presented to 1he Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of English University of Virginia August 1996 WARNING! The document you now hold in your hands is a feeble reproduction of an experiment in hypertext. In the waning years of the twentieth century, a crude network of computerized information centers formed a system called the Internet; one particular format of data retrieval combined text and digital images and was known as the World Wide Web. This particular project was designed for viewing through Netscape 2.0. It can be found at http://xroads.virginia.edu/~MA96/PUCK/ If you are able to locate this Website, you will soon realize it is a superior resource for the presentation of such a highly visual magazine as Puck. 11 Table of Contents Introduction 1 I) A Brief History of Cartoons 5 II) Popular and Elite Political Culture 13 III) A Popular Medium 22 "Our National Dog Show" 32 "Inspecting the Democratic Curiosity Shop" 35 Caricature and the Carte-de-Viste 40 The Campaign Against Grant 42 EndNotes 51 Bibliography 54 1 wWhy can the United States not have a comic paper of its own?" enquired E.L. Godkin of The Nation, one of the most distinguished intellectual magazines of the Gilded Age. America claimed a host of popular and insightful raconteurs as its own, from Petroleum V. -

(July-November 1863) Lincoln's Popularit

Chapter Thirty-one “The Signs Look Better”: Victory at the Polls and in the Field (July-November 1863) Lincoln’s popularity soared after the victories at Gettysburg, Vicksburg, and Port Hudson. His old friend from Illinois, Jesse W. Fell, reflected the changed public mood. In August, Fell told Lyman Trumbull that during the early stages of the war, “I did not like some things that were done, and many things that were not done, by the present Administration.” Along with most “earnest, loyal men, I too was a grumbler, because, as we thought, the Gov't. moved too slow.” But looking back, Fell acknowledged that “we are not now disposed to be sensorious [sic] to the ‘powers that be,’ even among ourselves.” To the contrary, “it is now pretty generally conceded, that, all things considered, Mr. Lincoln's Administration has done well.” Such “is the general sentiment out of Copperhead Circles.” Lincoln had been tried, and it was clear “that he is both honest and patriotic; that if he don't go forward as fast as some of us like, he never goes backwards.”1 To a friend in Europe, George D. Morgan explained that the president “is very popular and good men of all sides seem to regard him as the man for the place, for they see what one cannot see abroad, how difficult the position he has to fill, to keep 1 Fell to Lyman Trumbull, Cincinnati, 11 August 1863, Trumbull Papers, Library of Congress. 3378 Michael Burlingame – Abraham Lincoln: A Life – Vol. 2, Chapter 31 the border States quiet, to keep peace with the different generals, and give any satisfaction to the radicals.”2 One of those Radicals, Franklin B. -

Gold Democrats and the Decline of Classical Liberalism, 1896–1900

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 Gold Democrats and the Decline of Classical Liberalism, 1896–1900 —————— ✦ —————— DAVID T. BEITO AND LINDA ROYSTER BEITO n 1896 a new political party was born, the National Democratic Party (NDP). The founders of the NDP included some of the leading exponents of classical I liberalism during the late nineteenth century. Few of those men, however, fore- saw the ultimate fate of their new party and of the philosophy of limited government that it championed.