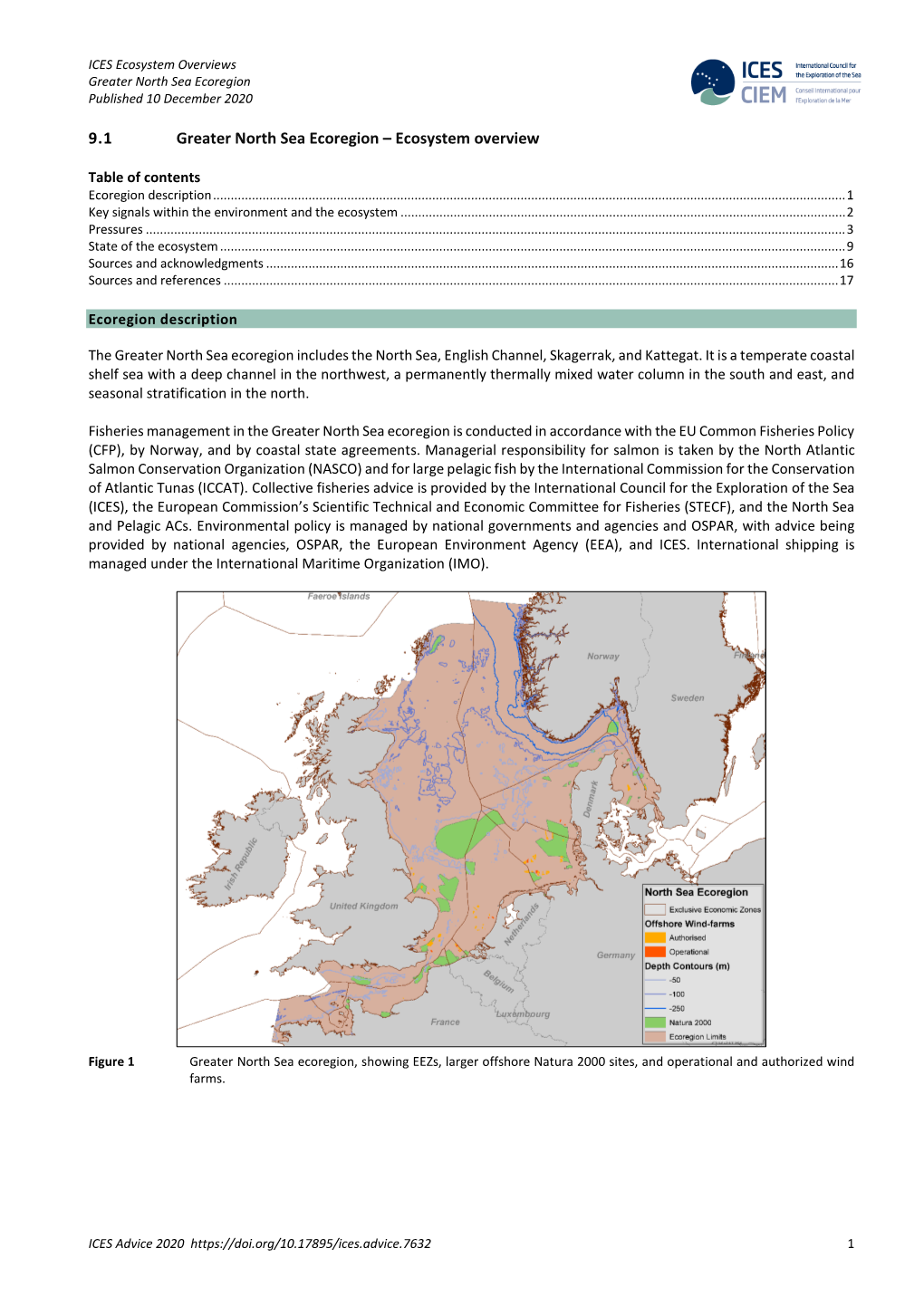

Greater North Sea Ecoregion Published 10 December 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cod Fact Sheet

R FACT SHEET Cod (Gadus morhua) Image taken from (Cohen et al. 1990) Introduction Cod (Gadus morhua) is generally considered a demersal fish although its habitat may become pelagic under certain hydrographic conditions, when feeding or spawning. It is widely distributed throughout the north Atlantic and Arctic regions in a variety of habitats from shoreline to continental shelf, in depths to 600m (Cohen et al. 1990). The Irish Sea stock spawns at two main sites in the western and eastern Irish Sea during February to April (Armstrong et al. 2011). Historically the stock has been commercially important, however in the last decade a decline in SSB and reduced productivity of the stock have led to reduce landings. Reviewed distribution map for Gadus morhua (Atlantic cod), with modelled year 2100 native range map based on IPCC A2 emissions scenario. www.aquamaps.org, version of Aug. 2013. Web. Accessed 28 Jan. 2011 Life history overview Adults are usually found in deeper, colder waters. During the day they form schools and swim about 30-80 m above the bottom, dispersing at night to feed (Cohen et al. 1990; ICES 2005). They are omnivorous; feeding at dawn or dusk on invertebrates and fish, including their own young (Cohen et al. 1990). Adults migrate between spawning, feeding and overwintering areas, mostly within the boundaries of the respective stocks. Large migrations are rare occurrences, although there is evidence for limited seasonal migrations into neighbouring regions, most Irish Sea fish will stay within their management area (ICES 2012). Historical tagging studies indicated spawning site fidelity but with varying degrees of mixing of cod between the Irish Sea, Celtic Sea and west of Scotland/north of Ireland (ICES 2015). -

Shrimp Fishing in Mexico

235 Shrimp fishing in Mexico Based on the work of D. Aguilar and J. Grande-Vidal AN OVERVIEW Mexico has coastlines of 8 475 km along the Pacific and 3 294 km along the Atlantic Oceans. Shrimp fishing in Mexico takes place in the Pacific, Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean, both by artisanal and industrial fleets. A large number of small fishing vessels use many types of gear to catch shrimp. The larger offshore shrimp vessels, numbering about 2 212, trawl using either two nets (Pacific side) or four nets (Atlantic). In 2003, shrimp production in Mexico of 123 905 tonnes came from three sources: 21.26 percent from artisanal fisheries, 28.41 percent from industrial fisheries and 50.33 percent from aquaculture activities. Shrimp is the most important fishery commodity produced in Mexico in terms of value, exports and employment. Catches of Mexican Pacific shrimp appear to have reached their maximum. There is general recognition that overcapacity is a problem in the various shrimp fleets. DEVELOPMENT AND STRUCTURE Although trawling for shrimp started in the late 1920s, shrimp has been captured in inshore areas since pre-Columbian times. Magallón-Barajas (1987) describes the lagoon shrimp fishery, developed in the pre-Hispanic era by natives of the southeastern Gulf of California, which used barriers built with mangrove sticks across the channels and mouths of estuaries and lagoons. The National Fisheries Institute (INP, 2000) and Magallón-Barajas (1987) reviewed the history of shrimp fishing on the Pacific coast of Mexico. It began in 1921 at Guaymas with two United States boats. -

Physical Geography Research Project

Name Date Physical Geography Research Project Your small group will be assigned one of the following examples. Use the provided websites to conduct research and answer the questions for your assigned example. Example 1: The North Sea Humans have divided land into governed territories for centuries. But what happens when a body of water needs to be divided up because of a natural resource? That is what happened in the North Sea after oil was discovered in the 1960s. The countries that surround the North Sea include the United Kingdom, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Germany, Denmark, and Norway. Research how the countries that border the North Sea have divided up the claim. If possible, find information on the United Nations Law of the Sea Treaty and exclusive economic zones (EEZ). 1. Do you think the way the North Sea was split was fair to all countries involved? Why or why not? ____________________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________________ 2. How do you think dividing up a claim like this affects the relationships between the countries involved? Support your opinion with evidence. __________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________________________________________________ 3. Are there other areas of Europe where natural resources -

6 North Sea 6.1 Ecosystem Overview 6.1.1 Ecosystem Components

6 North Sea 6.1 Ecosystem overview 6.1.1 Ecosystem components Seabed topography and substrates The topography of the North Sea can be broadly described as having a shallow (<50 m) southeastern part, which is sharply separated by the Dogger Bank from a much deeper (50–100 m) central part that runs north along the British coast. The central northern part of the shelf gradually slopes down to 200 m before reaching the shelf edge. Another main feature is the Norwegian Trench running east along the Norwegian coast into the Skagerrak with depths up to 500 m. Further to the east, the Norwegian Trench ends abruptly, and the Kattegat is of depths similar to the main part of the North Sea (Figure 6.1.1). The substrates are dominated by sands in the southern and coastal regions and fine muds in deeper and more central parts (Figure 6.1.2). Sands become generally coarser to the east and west, with patches of gravel and stones existing as well. In the shallow southern part, concentrations of boulders may be found locally, originating from transport by glaciers during the ice ages. This specific hard-bottom habitat has become scarcer, because boulders caught in beam trawls are often brought ashore. The area around, and to the west of the Orkney/Shetland archipelago is dominated by coarse sand and gravel. The deep areas of the Norwegian Trench are covered with extensive layers of fine muds, while some of the slopes have rocky bottoms. Several underwater canyons extend further towards the coasts of Norway and Sweden. -

Bathymetry and Active Geological Structures in the Upper Gulf of California Luis G

BOLETÍN DE LA SOCIEDAD GEOLÓ G ICA MEXICANA VOLU M EN 61, NÚ M . 1, 2009 P. 129-141 Bathymetry and active geological structures in the Upper Gulf of California Luis G. Alvarez1*, Francisco Suárez-Vidal2, Ramón Mendoza-Borunda2, Mario González-Escobar3 1 Departamento de Oceanografía Física, División de Oceanología. 2 Departamento de Geología, División de Ciencias de la Tierra. 3 Departamento de Geofísica Aplicada, División de Ciencias de la Tierra. Centro de Investigación Científica y de Educación Superior de Ensenada, B.C. Km 107 carretera Tijuana-Ensenada, Ensenada, Baja California, México, 22860. * Corresponding author: E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Bathymetric surveys made between 1994 and 1998 in the Upper Gulf of California revealed that the bottom relief is dominated by narrow, up to 50 km long, tidal ridges and intervening troughs. These sedimentary linear features are oriented NW-SE, and run across the shallow shelf to the edge of Wagner Basin. Shallow tidal ridges near the Colorado River mouth are proposed to be active, while segments in deeper water are considered as either moribund or in burial stage. Superposition of seismic swarm epicenters and a seismic reflection section on bathymetric features indicate that two major ridge-troughs structures may be related to tectonic activity in the region. Off the Sonora coast the alignment and gradient of the isobaths matches the extension of the Cerro Prieto Fault into the Gulf. A similar gradient can be seen over the west margin of the Wagner Basin, where in 1970 a seismic swarm took place (Thatcher and Brune, 1971) overlapping with a prominent ridge-trough structure in the middle of the Upper Gulf. -

1. a Plankton Highway Along the Western Coasts of the UK

HABs themselves should not be used as indicator 1. A plankton highway along of water quality. the western coasts of the UK Main policy implications This work has demonstrated that the stratified regions around the western coasts of the UK and Ireland have particular unique properties and constitute distinct eco-hydrodynamic regions. Such oceanographic regionality is directly relevant to a range of aspects likely to be considered in the Marine Bill, especially Marine Spatial Planning (http://www.defra.gov.uk/corporate/consult/marine bill/index.htm). Use of such knowledge is fundamental to the characterisation (‘typology’) of UK shelf waters (relevant to the proposed European Marine Strategy Directive), and increasing awareness is required of these oceanographic complexities with regard to, for example, the consideration of indicators of ecosystem status (Tett et al., 2004a, b; Larcombe et al. 2004), fisheries management and marine nature conservation. In summer, the density-driven flows at the boundaries of the stratified regions cause a major regional flow, which acts to limit transport between neighbouring eco-hydrodynamic regions. For example, summer transport between the Celtic Sea and the Irish Sea is very limited, while there is strong transport along their boundary (St Georges Channel). There is thus limited potential for transport of plankton across these pathways, Figure 1.1. The combined pathway from the results of three but high potential for transport along them, as field programs, with drifter tracks overlain on the contours of indicated by the occurrence of Karenia mikimotoi bottom density field. along this pathway (Raine, 1993). This mechanism has the potential to transport ‘non- Main science findings indigenous’ species into and around UK waters, into environments that may, in the future, be From early summer (late May) to autumn (mid favourable to their persistence. -

SESSION I : Geographical Names and Sea Names

The 14th International Seminar on Sea Names Geography, Sea Names, and Undersea Feature Names Types of the International Standardization of Sea Names: Some Clues for the Name East Sea* Sungjae Choo (Associate Professor, Department of Geography, Kyung-Hee University Seoul 130-701, KOREA E-mail: [email protected]) Abstract : This study aims to categorize and analyze internationally standardized sea names based on their origins. Especially noting the cases of sea names using country names and dual naming of seas, it draws some implications for complementing logics for the name East Sea. Of the 110 names for 98 bodies of water listed in the book titled Limits of Oceans and Seas, the most prevalent cases are named after adjacent geographical features; followed by commemorative names after persons, directions, and characteristics of seas. These international practices of naming seas are contrary to Japan's argument for the principle of using the name of archipelago or peninsula. There are several cases of using a single name of country in naming a sea bordering more than two countries, with no serious disputes. This implies that a specific focus should be given to peculiar situation that the name East Sea contains, rather than the negative side of using single country name. In order to strengthen the logic for justifying dual naming, it is suggested, an appropriate reference should be made to the three newly adopted cases of dual names, in the respects of the history of the surrounding region and the names, people's perception, power structure of the relevant countries, and the process of the standardization of dual names. -

Greater North Sea Ecoregion Published 12 December 2019

ICES Ecosystem Overviews Greater North Sea Ecoregion Published 12 December 2019 9.1 Greater North Sea Ecoregion – Ecosystem overview Table of contents Ecoregion description ................................................................................................................................................................................... 1 Key signals within the environment and the ecosystem .............................................................................................................................. 2 Pressures ...................................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 State of the ecosystem ............................................................................................................................................................................... 10 Sources and acknowledgments .................................................................................................................................................................. 18 Sources and references .............................................................................................................................................................................. 19 Ecoregion description The Greater North Sea ecoregion includes the North Sea, English Channel, Skagerrak, and Kattegat. It is a temperate coastal shelf sea with a deep channel in the northwest, a permanently thermally -

North Sea Atlas

MEFEPO Making the European Fisheries Ecosystem Plan Operational North Sea Atlas August 2009 Welcome to MEFEPO “ The oceans and the seas sustain the livelihoods of hundreds of millions of people, as a source of food and energy, as an avenue for trade and communications and as a recreational and scenic asset for tourism in coastal regions. So their contribution to the economic prosperity of present and future generations cannot be underestimated .” Jose Manual Barroso, President EU Commission EU Green Paper on Maritime Policy, 2006 2 Welcome to MEFEPO Preface Welcome to the MEFEPO Atlas! This publication is intended for policy makers, managers and other interested stakeholders. Its purpose is to provide a general ecosystem overview of the North Sea (NS) Regional Advisory Council (RAC) area. We cannot cover all aspects of the complex North Sea ecosystem, but we can highlight the key features and give a broad overview. In the Atlas we have tried to make the science as clear and concise as possible. We have kept the technical language to a minimum and presented the information through a blend of text, tables, figures and images. There is a glossary of terms (p.76-77) and a list of more detailed scientific references (p.78-79), if you would like to follow up certain issues. The Atlas includes general summary information on the physical and chemical features, habitat types, biological features, fishing activity and other human activities of the North Sea region. Background material on five North Sea case study fisheries are presented (flatfish, sandeel, herring, mixed whitefish and Nephrops). -

Implementation of Berlin Process in the Western Balkans Countries

Regional Convention on European Integration of the Western Balkans IMPLEMENTATION OF BERLIN PROCESS IN THE WESTERN BALKANS COUNTRIES Project - “Together for EU Enlargement - V4 and WB Strengthening Cohesion of EU Integration and Berlin process” 1 Regional Convention on European Integration of the Western Balkans IMPLEMENTATION OF BERLIN PROCESS IN THE WESTERN BALKANS COUNTRIES REGIONAL STUDY Project - “Together for EU Enlargement - V4 and WB Strengthening Cohesion of EU Integration and Berlin process” 2 3 REGIONAL STUDY Implementation of Berlin Process in the Western Balkans Countries Publisher European Movement in Montenegro For publisher Momčilo Radulović Editor Momčilo Radulović Proofreading Ana Spahić and Luka Martinović Design DAA Montenegro Printing Monargo Circulation 300 European Movement in Montenegro (EMIM) Vasa Raičkovića 9, 81000 Podgorica Tel/Fax: 020/268-651; Email: [email protected] Web: www.emim.org Note: The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Visegrad Fund nor European Movement in Montenegro. 4 5 CONTENTS I. Montenegro in the Berlin Process: Important Strides Made, Major Impact Yet to be Visible 11 1. Background 11 2. Montenegro in the Western Balkan Summits 12 3. Montenegro and the Western Balkans Investment Framework 13 • Transport 17 • Environment 20 • Energy 21 4. P2P connectivity, Youth and Civil Society Organizations in the Berlin Process 23 5. Conclusion 25 II. Albania in the Berlin Process 27 1. Background 27 2. Connectivity Agenda Investment Projects in Albania 27 • Tirana-Durrës-Rinas Railway (Mediterranean Corridor) 28 • Rehabilitation of the Durrës Port, Quais 1 and 2 29 • Energy interconnection line Albania - Northern Macedonia (I): Albania Section 29 • Broadband infrastructure project 29 • Adriatic-Jonian Corridor: Albanian leg 29 3. -

Atlantic Herring (Clupea Harengus) in the Irish and Celtic Seas; Tracing Populations of the Past and Present

Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus) in the Irish and Celtic Seas; tracing populations of the past and present Nóirín D. Burke A thesis submitted to the School of Science, Galway Mayo Institute of Technology in fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Life and Physical Sciences June 2008 Head of Department: Dr Seamus Lennon Supervisors: Dr Deirdre Brophy Dr Pauline A. King Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology, Dublin Rd., Galway, Ireland TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: General Introduction……………………………………………........... 10 1.1 Herring biology and population structure………………………. 10 1.2 Herring fisheries around Ireland………………………………... 12 1.3 Stock structure of Celtic and Irish Sea herring………………….. 14 1.4 Herring assessments in the Irish and Celtic Seas……………….. 15 1.5 Otolith applications in fisheries science………………………… 16 1.6 Otolith microstructure……………...……………………………. 17 1.7 Otolith morphometrics and shape analysis……………………… 18 1.8 Summary of objectives………………………………………….. 19 Chapter 2: Shape analysis of otolith annuli in Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus); a new method for tracking fish populations………………………….. 23 2.1 Abstract………………………………………………………….. 23 2.2 Introduction……………………………………………………… 23 2.3 Methods………………………………………………………….. 26 2.4 Results…………………………………………………………… 32 2.5 Discussion……………………………………………………….. 33 2.6 Conclusion……………………………………………………….. 40 Chapter 3: Otolith shape analysis, its applications to distinguishing between Irish and Celtic Sea herring (Clupea harengus) stocks in the Irish Sea……………….. 49 3.1 Abstract………………………………………………………….. 49 3.2 Introduction……………………………………………………… 49 3.3 Methods…………………………………………………………. 51 3.4 Results…………………………………………………………… 54 3.5 Discussion……………………………………………………….. 55 3.6 Conclusion……………………………………………………….. 57 Chapter 4: Otolith shape analysis provides evidence of natal homing in Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus)………………………………………………………… 62 4.1 Abstract………………………………………………………….. 62 4.2 Introduction……………………………………………………… 62 4.3 Methods…………………………………………………………. -

Celtic Seas Ecoregion – Ecosystem Overview

ICES Ecosystem Overviews Celtic Seas Ecoregion Published 14 December 2018 https://doi.org/ 10.17895/ices.pub.4667 7.1 Celtic Seas Ecoregion – Ecosystem overview Ecoregion description The Celtic Seas ecoregion covers the northwestern shelf seas of the EU. It includes areas of the deeper eastern Atlantic Ocean and coastal seas that are heavily influenced by oceanic inputs. The ecoregion ranges from north of Shetland to Brittany in the south. Three key areas constitute this ecoregion: • the Malin shelf; • the Celtic Sea and west of Ireland; • the Irish Sea. The Celtic Seas ecoregion includes all or parts of the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of three EU Member States. Fisheries in the Celtic Seas are managed through the EU Common Fisheries Policy (CFP), with fisheries of some stocks managed by the North East Atlantic Fisheries Commission (NEAFC) and by coastal state agreements. Responsibility for salmon fisheries is taken by the North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organization (NASCO) and for large pelagic fish by the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT). Collective fisheries advice is provided by the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES), the European Commission’s Scientific Technical and Economic Committee for Fisheries (STECF), and the North Western Waters and Pelagic ACs. Environmental policy is managed by national governments and agencies and by OSPAR; advice is provided by national agencies, OSPAR, the European Environment Agency (EEA), and ICES. International shipping is managed under the International Maritime Organization (IMO). Figure 1 The Celtic Seas ecoregion, showing EEZs, larger offshore Natura 2000 sites, and operational and authorized wind farms.