Quality Status Report 2000: Region III – Celtic Seas. OSPAR Commission

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cod Fact Sheet

R FACT SHEET Cod (Gadus morhua) Image taken from (Cohen et al. 1990) Introduction Cod (Gadus morhua) is generally considered a demersal fish although its habitat may become pelagic under certain hydrographic conditions, when feeding or spawning. It is widely distributed throughout the north Atlantic and Arctic regions in a variety of habitats from shoreline to continental shelf, in depths to 600m (Cohen et al. 1990). The Irish Sea stock spawns at two main sites in the western and eastern Irish Sea during February to April (Armstrong et al. 2011). Historically the stock has been commercially important, however in the last decade a decline in SSB and reduced productivity of the stock have led to reduce landings. Reviewed distribution map for Gadus morhua (Atlantic cod), with modelled year 2100 native range map based on IPCC A2 emissions scenario. www.aquamaps.org, version of Aug. 2013. Web. Accessed 28 Jan. 2011 Life history overview Adults are usually found in deeper, colder waters. During the day they form schools and swim about 30-80 m above the bottom, dispersing at night to feed (Cohen et al. 1990; ICES 2005). They are omnivorous; feeding at dawn or dusk on invertebrates and fish, including their own young (Cohen et al. 1990). Adults migrate between spawning, feeding and overwintering areas, mostly within the boundaries of the respective stocks. Large migrations are rare occurrences, although there is evidence for limited seasonal migrations into neighbouring regions, most Irish Sea fish will stay within their management area (ICES 2012). Historical tagging studies indicated spawning site fidelity but with varying degrees of mixing of cod between the Irish Sea, Celtic Sea and west of Scotland/north of Ireland (ICES 2015). -

The Wave and Tidal Resource of Scotland

Renewable Energy 114 (2017) 3e17 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Renewable Energy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/renene The wave and tidal resource of Scotland * Simon P. Neill a, , Arne Vogler€ b, Alice J. Goward-Brown a, Susana Baston c, Matthew J. Lewis a, Philip A. Gillibrand d, Simon Waldman c, David K. Woolf c a School of Ocean Sciences, Bangor University, Marine Centre Wales, Menai Bridge, UK b University of the Highlands and Islands, Lews Castle College, Stornoway, Isle of Lewis, UK c International Centre for Island Technology, Heriot-Watt University, Old Academy, Back Road, Stromness, Orkney, UK d Environmental Research Institute, North Highland College, University of the Highlands and Islands, Thurso, UK article info abstract Article history: As the marine renewable energy industry evolves, in parallel with an increase in the quantity of available Received 7 July 2016 data and improvements in validated numerical simulations, it is occasionally appropriate to re-assess the Received in revised form wave and tidal resource of a region. This is particularly true for Scotland - a leading nation that the 14 February 2017 international community monitors for developments in the marine renewable energy industry, and Accepted 11 March 2017 which has witnessed much progress in the sector over the last decade. With 7 leased wave and 17 leased Available online 16 March 2017 tidal sites, Scotland is well poised to generate significant levels of electricity from its abundant natural marine resources. In this state-of-the-art review of Scotland's wave and tidal resource, we examine the Keywords: Marine renewable energy theoretical and technical resource, and provide an overview of commercial progress. -

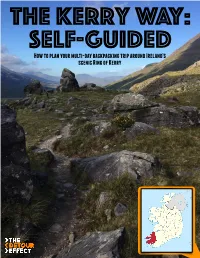

The Kerry Way Self Guided | Free Download

The Kerry Way: Self-Guided How to plan your multi-day backpacking trip around Ireland’s scenic Ring of Kerry Many are familiar with the beautiful Ring of Kerry in County Kerry, Ireland, but far fewer are aware that the entire route can be walked instead of driven. Despite The Kerry Way’s status as one of the most popular of Ireland’s National Waymarked Trails, I had more difficulty finding advice to help me prepare for it than I did for hikes in Scotland and the United Kingdom. At approximately 135 miles, it’s also the longest of Ireland’s trails, and in retrospect I’ve noticed that many companies who offer self-guided itineraries actually cut off two whole sections of the route - in my opinion, some of the prettiest sections. In honor of completing my own trek with nothing but online articles and digital apps to guide the way, I thought I’d pay it forward by creating my own budget-minded backpacker’s guide (for the WHOLE route) so that others might benefit from what I learned. If you prefer to stay in B&Bs rather than camping or budget accommodations, I’ve outlined how you can swap out some of my choices for your own. Stats: English Name: The Kerry Way Irish Name: Slí Uíbh Ráthaigh Location: Iveragh Peninsula, County Kerry, Ireland Official Length: 135 miles (217 km), but there are multiple route options Completion Time: 9 Days is the typical schedule High Point: 1,263ft (385m) at Windy Gap, between Glencar and Glenbeigh Route Style: Circular Loop Table of Contents: (Click to Jump To) Preparedness: Things to Consider Weather Gear Amenities Currency Language Wildlife Cell Service Physical Fitness Popularity Waymarking To Camp or Not to Camp? Emergencies Resources Getting There // Getting Around Route // Accommodations Preparedness: Things to Consider WEATHER According to DiscoveringIreland, “the average number of wet days (days with more than 1mm of rain) ranges from about 150 days a year along the east and south-east coasts, to about 225 days a year in parts of the west.” Our route along the Iveragh Peninsula follows the southwest coast of Ireland. -

Ireland's 6Th National Report to The

IRELAND IRELAND 6th National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity Citation:DCHG 2019. Ireland’s 6th National Report to the Convention on Biological Diversity. Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht. Report prepared by: Craig Bullock (Optimize), Rachel Morrison, Noeleen Smyth* (National Botanic Gardens), Tomás Murray (National Biodiversity Data Centre) & Deirdre Lynn (National Parks and Wildlife Service). Contributions from: Katherine Duff (Forest Service), Hannah Denniston (DAFM), Una Fitzpatrick (NBDC), John Lusby (Birdwatch), Oonagh Duggan (Birdwatch), Derek McLoughlin (exRBAPs), Daire O’hUallachain (Teagasc), Nathy Gilligan (OPW), Mark Adamson (OPW), Kevin Collins (Forest Service), Hannah Hamilton (Eirewild), Ciaran O’Keeffe (National Parks and Wildlife Service, Andy Bleasdale (NPWS), Barry O’Donoghue (NPWS), Ferdia Marnell (NPWS), Barry O’Donoghue (NPWS), Brian Lucas (NPWS), Gerry Lecky (NPWS), Catherine Vernor (NPWS), Dave Tierney (NPWS), Yvonne Leahy (NPWS), Sarah Ui Bhroin (NPWS), Jenny Fuller (NPWS), Alan Walsh (LAWCO), Michael Kane (LAWCO), Donal Daly (exEPA), Florence Renou (UCD), Gerry Brady (CSO), Clare O’Hara (CSO), Brian Deegan (Irish Water), Francis O’Beirn (Marine Institute), Ciaran Nugent (DAFM), Karin Dubsky (Coastwatch), Emma Higgs (WRI), Martin Walker (AGS), Karin Dubsky (Coastwatch), Shirley Clerkin (Local Authority), Roger Harrington (DHPLG). *See Section V for further list of contributors Cover photo: Colchicum autumnale L. also known as meadow saffron, autumn crocus or naked ladies is an endangered, -

High Resolution Ph Measurements Using a Lab-On-Chip Sensor in Surface Waters of Northwest European Shelf Seas

sensors Article High Resolution pH Measurements Using a Lab-on-Chip Sensor in Surface Waters of Northwest European Shelf Seas Victoire M. C. Rérolle 1, Eric P. Achterberg 1,2,* ID , Mariana Ribas-Ribas 1,3 ID , Vassilis Kitidis 4 ID , Ian Brown 4, Dorothee C. E. Bakker 5, Gareth A. Lee 5 and Matthew C. Mowlem 6 1 National Oceanography Centre, Southampton, University of Southampton, Southampton SO14 3ZH, UK; v.rerolle@fluidion.com (V.M.C.R.); [email protected] (M.R.-R.); 2 GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, 24148 Kiel, Germany 3 Institute for Chemistry and Biology of the Marine Environment, University of Oldenburg, 26382 Wilhelmshaven, Germany 4 Plymouth Marine Laboratory, Prospect Place, Plymouth PL1 3DH, UK; [email protected] (V.K.); [email protected] (I.B.) 5 Centre of Ocean and Atmospheric Sciences, School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia, Norwich NR4 7TJ, UK; [email protected] (D.C.E.B.); [email protected] (G.A.L.) 6 National Oceanography Centre, Southampton SO14 3ZH, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 2 July 2018; Accepted: 4 August 2018; Published: 10 August 2018 Abstract: Increasing atmospheric CO2 concentrations are resulting in a reduction in seawater pH, with potential detrimental consequences for marine organisms. Improved efforts are required to monitor the anthropogenically driven pH decrease in the context of natural pH variations. We present here a high resolution surface water pH data set obtained in summer 2011 in North West European Shelf Seas. -

Expedited Assessment Public Comment Draft Report SFSAG North Sea Haddock

MSC Full Assessment Reporting Template FCR v2.0 (16th March 2015) MEC V1.1 (2nd October 2017) Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) Expedited Assessment Public Comment Draft Report SFSAG North Sea haddock On behalf of Scottish Fisheries Sustainable Accreditation Group (SFSAG) Prepared by ME Certification Ltd April 2018 Authors: Dr Hugh Jones Dr Robin Cook Dr Jo Gascoigne Dr Geir Hønneland ME Certification Ltd 56 High Street, Lymington Hampshire SO41 9AH United Kingdom Tel: 01590 613007 Fax: 01590 671573 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.me-cert.com MSC Full Assessment Reporting Template FCR v2.0 (16th March 2015) MEC V1.1 (2nd October 2017) Contents GLOSSARY ............................................................................................................................. 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................. 6 1 AUTHORSHIP AND PEER REVIEWERS .............................................................................. 10 2 DESCRIPTION OF THE FISHERY ....................................................................................... 12 2.1 Unit(s) of Assessment (UoA) and Scope of Certification Sought ........................... 12 2.1.1 UoAs and Proposed Unit of Certifications (UoC) .......................................................... 12 2.1.2 Extension of scope of fishery certificate (expedited assessment). ............................... 12 2.1.3 Final UoC(s) ................................................................................................................. -

1. a Plankton Highway Along the Western Coasts of the UK

HABs themselves should not be used as indicator 1. A plankton highway along of water quality. the western coasts of the UK Main policy implications This work has demonstrated that the stratified regions around the western coasts of the UK and Ireland have particular unique properties and constitute distinct eco-hydrodynamic regions. Such oceanographic regionality is directly relevant to a range of aspects likely to be considered in the Marine Bill, especially Marine Spatial Planning (http://www.defra.gov.uk/corporate/consult/marine bill/index.htm). Use of such knowledge is fundamental to the characterisation (‘typology’) of UK shelf waters (relevant to the proposed European Marine Strategy Directive), and increasing awareness is required of these oceanographic complexities with regard to, for example, the consideration of indicators of ecosystem status (Tett et al., 2004a, b; Larcombe et al. 2004), fisheries management and marine nature conservation. In summer, the density-driven flows at the boundaries of the stratified regions cause a major regional flow, which acts to limit transport between neighbouring eco-hydrodynamic regions. For example, summer transport between the Celtic Sea and the Irish Sea is very limited, while there is strong transport along their boundary (St Georges Channel). There is thus limited potential for transport of plankton across these pathways, Figure 1.1. The combined pathway from the results of three but high potential for transport along them, as field programs, with drifter tracks overlain on the contours of indicated by the occurrence of Karenia mikimotoi bottom density field. along this pathway (Raine, 1993). This mechanism has the potential to transport ‘non- Main science findings indigenous’ species into and around UK waters, into environments that may, in the future, be From early summer (late May) to autumn (mid favourable to their persistence. -

Table of Contents

Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on September 28, 2021 Contents PARNELL, J. Basins on the Atlantic seaboard: introduction vii Basin histories and hydrocarbon source rocks PARNELL, J. Burial histories and hydrocarbon source rocks on the North West Seaboard 3 STEIN, A. M. Basin development and petroleum potential in The Minches and Sea of the Hebrides Basins 17 DEAN, M. T. Conodont colour maturation indices for the Carboniferous of west-central Scotland 21 MOSSMAN, D. J. Carboniferous source rocks of the Canadian Atlantic margin 25 THRASHER, J. Thermal effect of the Tertiary Cuillins Intrusive Complex in the Jurassic of the Hebrides: an organic geochemical study 35 Introduction to Mesozoic basins on the North West Seaboard MORTON, N. Late Triassic to Middle Jurassic stratigraphy, palaeogeography and tectonics west of the British Isles 53 The Hebridean basins and adjacent areas MCKEEVER, P. Petrography and diagenesis of the Permo-Triassic of Scotland 71 Appendix. MCKEEVER, P., CAREY, P. & QUINN, J. Authigenic k-feldspar in the Permo- Triassic of northwest Britain: a pilot oxygen isotope study 93 MORTON, N. Dynamic stratigraphy of the Triassic and Jurassic of the Hebrides Basin, NW Scotland 97 HARRIS, J. P. Mid-Jurassic lagoonal delta systems in the Hebridean basins: thickness and facies distribution patterns of potential reservoir sandbodies 111 WILKINSON, M. Concretionary cements in Jurassic sandstones, Isle of Eigg, Inner Hebrides 145 HAMILTON, P. J., FALLICK,A. E., ANDREWS, J. E. & WHITFORD, D. J. Middle Jurassic clay- minerals from the Minch Basin: isotopic tracing of provenance and post-depositional alteration 155 LOWDEN, B., BRALEY, S., HURST, A. -

Appendix B. List of Special Areas of Conservation and Special Protection Areas

Appendix B. List of Special Areas of Conservation and Special Protection Areas Irish Water | Draft Framework Plan. Natura Impact Statement Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) in the Republic of Ireland Site code Site name 000006 Killyconny Bog (Cloghbally) SAC 000007 Lough Oughter and Associated Loughs SAC 000014 Ballyallia Lake SAC 000016 Ballycullinan Lake SAC 000019 Ballyogan Lough SAC 000020 Black Head-Poulsallagh Complex SAC 000030 Danes Hole, Poulnalecka SAC 000032 Dromore Woods and Loughs SAC 000036 Inagh River Estuary SAC 000037 Pouladatig Cave SAC 000051 Lough Gash Turlough SAC 000054 Moneen Mountain SAC 000057 Moyree River System SAC 000064 Poulnagordon Cave (Quin) SAC 000077 Ballymacoda (Clonpriest and Pillmore) SAC 000090 Glengarriff Harbour and Woodland SAC 000091 Clonakilty Bay SAC 000093 Caha Mountains SAC 000097 Lough Hyne Nature Reserve and Environs SAC 000101 Roaringwater Bay and Islands SAC 000102 Sheep's Head SAC 000106 St. Gobnet's Wood SAC 000108 The Gearagh SAC 000109 Three Castle Head to Mizen Head SAC 000111 Aran Island (Donegal) Cliffs SAC 000115 Ballintra SAC 000116 Ballyarr Wood SAC 000129 Croaghonagh Bog SAC 000133 Donegal Bay (Murvagh) SAC 000138 Durnesh Lough SAC 000140 Fawnboy Bog/Lough Nacung SAC 000142 Gannivegil Bog SAC 000147 Horn Head and Rinclevan SAC 000154 Inishtrahull SAC 000163 Lough Eske and Ardnamona Wood SAC 000164 Lough Nagreany Dunes SAC 000165 Lough Nillan Bog (Carrickatlieve) SAC 000168 Magheradrumman Bog SAC 000172 Meenaguse/Ardbane Bog SAC 000173 Meentygrannagh Bog SAC 000174 Curraghchase Woods SAC 000181 Rathlin O'Birne Island SAC 000185 Sessiagh Lough SAC 000189 Slieve League SAC 000190 Slieve Tooey/Tormore Island/Loughros Beg Bay SAC 000191 St. -

The Overall Density of Total Seabirds in the Surveyed Shore-Watch Area (E

RISK ASSESSMENT FOR MARINE MAMMAL AND SEABIRD POPULATIONS IN SOUTH- WESTERN IRISH WATERS (R.A.M.S.S.I.) Daphne Roycroft, Michelle Cronin, Mick Mackey, Simon N. Ingram Oliver O’Cadhla Coastal and Marine Resources Centre, University College Cork March 2007 HEA Higher Education Authority An tÚdarás um Ard-Oideachas CONTENTS i) Summary ii) Acknowledgements General Introduction Seabirds and marine mammals in southwest Ireland 2 Rationale for RAMSSI 6 Study sites 7 Inshore risks to seabirds and marine mammals 11 i. Surface pollution 11 ii. Ballast water 13 iii. Organochlorine pollution and antifoulants 14 iv. Disease 15 v. Acoustic pollution 15 vi. Disturbance from vessels 16 vii. Wind farming 17 viii. Mariculture 17 ix. Fisheries 19 Aims and Objective 22 References 23 Appendix 33 Chapter 1. Seabird distribution and habitat-use in Bantry Bay 1.1 Abstract 35 1.2 Introduction 35 1.3 Study site 37 1.4 Methods 37 1.4.1 Line transect techniques 37 1.4.2 Data preparation 40 1.4.3 Data analysis 45 1.5 Results 46 1.5.1 Modelling 46 1.5.2 Relative abundance 54 1.6 Discussion 59 1.7 References 66 1.8 Appendix 70 Chapter 2. Shore-based observations of seabirds in southwest Ireland 2.1 Abstract 72 2.2 Introduction 73 2.3 Methods 74 2.3.1 Shore-watch techniques 74 2.3.2 Analysis of relative abundance 75 2.3.3 Density calculation 77 2.3.4 Comparison of shore and boat-based densities 79 2.4 Results 80 2.4.1 Relative abundance 80 2.4.2 Density 87 2.5 Discussion 89 2.6 References 93 Chapter 3. -

Atlantic Herring (Clupea Harengus) in the Irish and Celtic Seas; Tracing Populations of the Past and Present

Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus) in the Irish and Celtic Seas; tracing populations of the past and present Nóirín D. Burke A thesis submitted to the School of Science, Galway Mayo Institute of Technology in fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Life and Physical Sciences June 2008 Head of Department: Dr Seamus Lennon Supervisors: Dr Deirdre Brophy Dr Pauline A. King Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology, Dublin Rd., Galway, Ireland TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1: General Introduction……………………………………………........... 10 1.1 Herring biology and population structure………………………. 10 1.2 Herring fisheries around Ireland………………………………... 12 1.3 Stock structure of Celtic and Irish Sea herring………………….. 14 1.4 Herring assessments in the Irish and Celtic Seas……………….. 15 1.5 Otolith applications in fisheries science………………………… 16 1.6 Otolith microstructure……………...……………………………. 17 1.7 Otolith morphometrics and shape analysis……………………… 18 1.8 Summary of objectives………………………………………….. 19 Chapter 2: Shape analysis of otolith annuli in Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus); a new method for tracking fish populations………………………….. 23 2.1 Abstract………………………………………………………….. 23 2.2 Introduction……………………………………………………… 23 2.3 Methods………………………………………………………….. 26 2.4 Results…………………………………………………………… 32 2.5 Discussion……………………………………………………….. 33 2.6 Conclusion……………………………………………………….. 40 Chapter 3: Otolith shape analysis, its applications to distinguishing between Irish and Celtic Sea herring (Clupea harengus) stocks in the Irish Sea……………….. 49 3.1 Abstract………………………………………………………….. 49 3.2 Introduction……………………………………………………… 49 3.3 Methods…………………………………………………………. 51 3.4 Results…………………………………………………………… 54 3.5 Discussion……………………………………………………….. 55 3.6 Conclusion……………………………………………………….. 57 Chapter 4: Otolith shape analysis provides evidence of natal homing in Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus)………………………………………………………… 62 4.1 Abstract………………………………………………………….. 62 4.2 Introduction……………………………………………………… 62 4.3 Methods…………………………………………………………. -

Celtic Seas Ecoregion – Ecosystem Overview

ICES Ecosystem Overviews Celtic Seas Ecoregion Published 14 December 2018 https://doi.org/ 10.17895/ices.pub.4667 7.1 Celtic Seas Ecoregion – Ecosystem overview Ecoregion description The Celtic Seas ecoregion covers the northwestern shelf seas of the EU. It includes areas of the deeper eastern Atlantic Ocean and coastal seas that are heavily influenced by oceanic inputs. The ecoregion ranges from north of Shetland to Brittany in the south. Three key areas constitute this ecoregion: • the Malin shelf; • the Celtic Sea and west of Ireland; • the Irish Sea. The Celtic Seas ecoregion includes all or parts of the Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZs) of three EU Member States. Fisheries in the Celtic Seas are managed through the EU Common Fisheries Policy (CFP), with fisheries of some stocks managed by the North East Atlantic Fisheries Commission (NEAFC) and by coastal state agreements. Responsibility for salmon fisheries is taken by the North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organization (NASCO) and for large pelagic fish by the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas (ICCAT). Collective fisheries advice is provided by the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES), the European Commission’s Scientific Technical and Economic Committee for Fisheries (STECF), and the North Western Waters and Pelagic ACs. Environmental policy is managed by national governments and agencies and by OSPAR; advice is provided by national agencies, OSPAR, the European Environment Agency (EEA), and ICES. International shipping is managed under the International Maritime Organization (IMO). Figure 1 The Celtic Seas ecoregion, showing EEZs, larger offshore Natura 2000 sites, and operational and authorized wind farms.