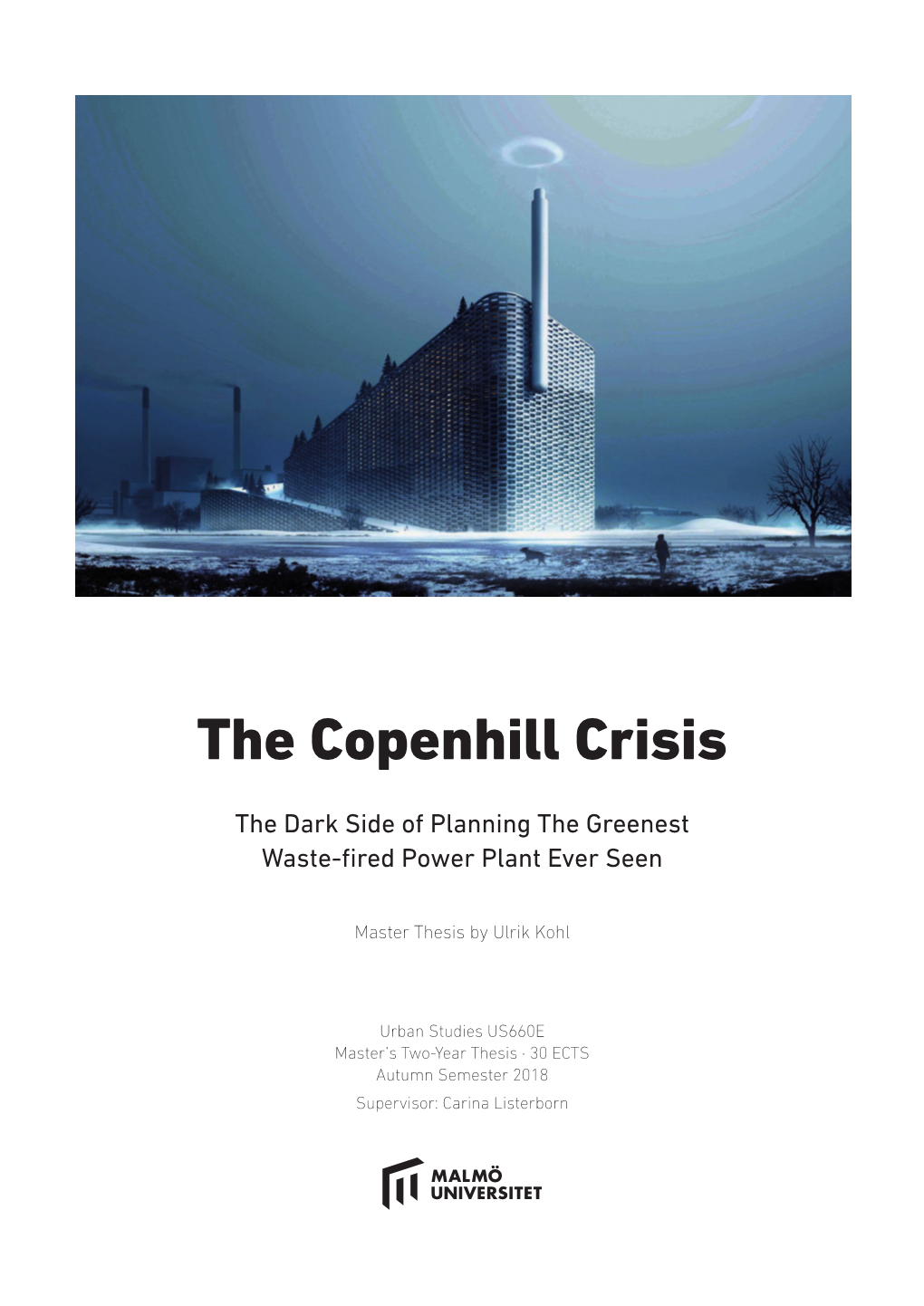

The Copenhill Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INNOVATION NETWORK »MORGENSTADT: CITY INSIGHTS« City Report

City report City of the Future INNOVATION NETWORK »MORGENSTADT: CITY INSIGHTS« »MORGENSTADT: »MORGENSTADT: CITY INSIGHTS« City Report ® INNOVATION NETWORK INNOVATION Project Management City Team Leader Fraunhofer Institute for Dr. Marius Mohr Industrial Engineering IAO Fraunhofer Institute for Nobelstrasse 12 Interfacial Engineering and 70569 Stuttgart Biotechnology IGB Germany Authors Contact Andrea Rößner, Fraunhofer Institute for lndustrial Engineering IAO Alanus von Radecki Arnulf Dinkel, Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems ISE Phone +49 711 970-2169 Daniel Hiller, Fraunhofer Institute for High-Speed Dynamics Ernst-Mach-Institut EMI Dominik Noeren, Fraunhofer Institute for Solar Energy Systems ISE COPENHAGEN [email protected] 2013 Hans Erhorn, Fraunhofer Institute for Building Physics IBP Heike Erhorn-Kluttig, Fraunhofer Institute for Building Physics IBP Dr. Marius Mohr, Fraunhofer Institute for lnterfacial Engineering and Biotechnology IGB OPENHAGEN © Fraunhofer-Gesellschaft, München 2013 Sylvia Wahren, Fraunhofer Institute for Manufacturing Engineering and Automation IPA C MORGENSTADT: CITY INSIGHTS (M:CI) Fraunhofer Institute for Industrial Engineering IAO Fraunhofer Institute for Factory Operation and Climate change, energy and resource scarcity, a growing Copenhagen has repeatedly been recognized as one Nobelstrasse 12 Automation IFF world population and aging societies are some of the of the cities with the best quality of life. Green growth 70569 Stuttgart Mailbox 14 53 large challenges of the future. In particular, these challen- and quality of life are the two main elements in Germany 39004 Magdeburg ges must be solved within cities, which today are already Copenhagen’s vision for the future. Copenhagen shall home to more than 50% of the world’s population. An be a leading green lab for sustainable urban solutions. -

GRETA - “Green Infrastructure: Enhancing Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services for Territorial Development”

GRETA - “GReen infrastructure: Enhancing biodiversity and ecosysTem services for territoriAl development” Applied Research Greater Copenhagen and Scania Version 30/07/2019 This applied research activity is conducted within the framework of the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme, partly financed by the European Regional Development Fund. The ESPON EGTC is the Single Beneficiary of the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme. The Single Operation within the programme is implemented by the ESPON EGTC and co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund, the EU Member States and the Partner States, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. This delivery does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the members of the ESPON 2020 Monitoring Committee. Authors Elin Slätmo, Kjell Nilsson and Eeva Turunen, Nordregio (research institute under Nordic Council of Ministers, www.nordregio.org) (Sweden) Co- authors Hugo Carrao, Mirko Gregor - space4environment (Luxembourg) Jaume Fons, Raquel Ubach, Roger Milego, Anna Marín UAB (Spain) Katherine Irvine, Jessica Maxwell, Laure Kuhfuss, Scott Herrett The James Hutton Institute (UK) Gemma-Garcia Blanco TECNALIA (Spain) Advisory Group Project Support Team: Blanka Bartol (Slovenia), Kristine Kedo (Latvia), Julie Delcroix (EC, DG Research & Innovation), Josef Morkus (Czech Republic) ESPON EGTC: Michaela Gensheimer (Senior Project Expert), Laurent Frideres (Head of Unit Evidence and Outreach), Akos Szabo (Financial Expert). Acknowledgements We would like to thank the stakeholders in Greater Copenhagen and Scania - among others technical experts and officials in the city of Malmö and the city of Copenhagen, Region Skåne, the Business authority in Denmark - who generously collaborated with GRETA research and shared their insight into green infrastructure throught the online consultations, phone interviews and meetings. -

Finger Plan’ a Robust Urban Planning Success Based on Collaborative Governance

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 25/7/2019, SPi 12 The Copenhagen Metropolitan ‘Finger Plan’ A Robust Urban Planning Success Based on Collaborative Governance Eva Sørensen and Jacob Torfing The Long Shadow of a Post-War Expansion Plan The metropolitan area in the Danish capital of Copenhagen has successfully avoided both urban sprawl and overly dense and chaotic urbanization. The early adoption of a comprehensive and adaptive urban plan has created a well-balanced, award-winning metropolitan area that combines residential neighbourhoods with green areas and access to public transport. The urban plan was drafted seventy years ago and still governs urban planning practices in the greater Copenhagen area. Physical planning of urban developments is extremely complex due to con- flicting pressures on land use, contradictory socio-economic dynamics, uncertain prognoses and outcomes, multi-level governance structures, and limited public planning capacities. In addition, comprehensive planning of housing and sup- portive infrastructures often fails because planning experts dream up ambitious master plans that have little or no bearing on local conditions, knowledge, and needs and only enjoy modest political and popular support. Finally yet import- antly, socio-economic turbulence, shifting political priorities, and bureaucratic resistance may undermine stated planning objectives and preferred strategies for how to attain them. Against this background, it is surprising how successful the so-called ‘Finger Plan’ in Copenhagen has been in governing decades of urban expansion in ways that secure desired outcomes in terms of high quality urban living and continuous support for core planning objectives by elected politicians, public planners, private stakeholders, and citizens. The Finger Plan was conceived in the optimistic post-war years from 1945 to 1948 when pressure on land use outside the city centre was still limited. -

ADDRESSING the METROPOLITAN CHALLENGE in BARCELONA METROPOLITAN AREA Appendix

ADDRESSING THE METROPOLITAN CHALLENGE IN BARCELONA METROPOLITAN AREA Appendix. Case studies of five metropolitan areas: Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Greater Manchester, Stuttgart and Zürich Case Studies of Five Metropolitan Areas: Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Greater Manchester, Stuttgart and Zürich is part of the study Addressing Metropolitan Challenges in Barcelona Metropolitan Area, which was drafted by the Metropolitan Research Institute of Budapest for the Barcelona Metropolitan Area (AMB). The views expressed herein are those of the authors alone, and the AMB cannot be held responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained in this document. © Àrea Metropolitana de Barcelona June 2018 Table of contents Amsterdam . 29 Copenhagen ....................................................... 36 Greater Manchester ................................................ 42 Stuttgart .......................................................... 52 Zürich ............................................................. 60 Addressing the Metropolitan Challenge in AMB. Case Studies AMSTERDAM (Netherlands) 1. National level framework 1.1. Formal government system The Netherlands is a constitutional monarchy with that is, only binding to the administrative unit which a representative parliamentary democracy and a has developed them (OECD 2017a:21). Aside from decentralised unitary state, characterised by a strong establishing the general legal framework and setting a political tradition of broad consensus seeking in policy strategic course, the state defined -

Demologos Case Study Centrope

Institut für Regional- und Umweltwirtschaft Institute of Regional Development and Environment Andreas Novy, Lukas Lengauer, Daniela Coimbra de Souza Vienna in an emerging trans-border region: Socioeconomic development in Central Europe SRE-Discussion 2008/08 2008 Vienna in an emerging trans-border region: Socioeconomic development in Central Europe NOVY, Andreas1 LENGAUER, Lukas1 COIMBRA DE SOUZA, Daniela1 Abstract: Drawing upon a periodisation of socio-economic development based on the regulation approach, the paper conducts a historical spatial development analysis of Vienna in its broader territory and multi-level perspective. The National context and the East-West cleavages mark the geography of the study. This periodisation is the basis to understand the strategies of Vienna in changing territorialities, the social forces and discourses that are reflected in the present context of Europeanisation, internationalisation and integration of border regions. A critical institutionalist approach is used to analyse the hegemonic liberal and populist discourses and strategies. The lessons taken in this section build the path to outline windows of opportunity for progressive politics, which are sketch out in the last section of the article. The ideas exposed in the paper are partial results of broader research carried out in the frame of DEMOLOGOS, an EU financed project. Key-Words: Socio-economic development; Vienna; progressive politics; Post-Fordism, democracy 1 Respectively Professor, Research Assistant and Research Assistant/ Ph.D. Candidate at: Institute for Regional Development and Environment; Vienna University for Economics and Business Administration. Address: Nordbergstraße 15 /B 4.06 (UZA4) - A-1090 Wien/ Vienna, Austria Tel.: +43-(0)1-31336-4777 Fax: +43-(0)1-31336-705 Email: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] 1 Introduction This case study analyses the spatial dimension of socioeconomic development in Vienna. -

Copenhagen Arbitration Day

2020 COPENHAGEN ARBITRATION DAY The Arbitrator and the Law April 2, at the House of Industry Welcome to the COPENHAGEN ARBITRATION DAY 2020 Dear Colleagues, The Danish Institute of Arbitration (DIA) and ICC Denmark are very pleased to welcome you to the third Copenhagen Arbitration Day. We are honored to present an interesting program and it is with great pleasure that we thank our speakers, which are some of the most recognized practitioners in the field. The event takes place in the House of Industry - the headquarters of the Confederation of Danish Industry - which is located in the heart of Copenhagen just between the Tivoli Gardens and the Copenhagen City Hall where the vibrant city is mirrored in the ever-evolving color and glass facade of the building. The Copenhagen Arbitration Day is the central event of the Danish arbitration communi- ty’s calendar as it presents an unequalled opportunity to exchange knowledge on trends within the field of international arbitration and to create and renew a network of colleagues and business contacts in a cozy atmosphere. The conference will be followed by a drinks reception and dinner at the historical Hotel Scandic Palace. Situated in City Hall Square, it is just a few minutes walk from the conference venue. During the dinner, the International Arbitrator José Rosell will deliver a keynote address. The Copenhagen Arbitration Day will be followed by the second annual Nordic Arbitra- tion Day on Friday 3 April 2020, which is a full-day conference organized by the young arbitration practitioners’ associations in the Nordic region. -

European Spatial Development, the Polycentric EU Capital, and Eastern Enlargement Carola Hein Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Growth and Structure of Cities Faculty Research Growth and Structure of Cities and Scholarship 2006 European Spatial Development, the Polycentric EU Capital, and Eastern Enlargement Carola Hein Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/cities_pubs Part of the Architecture Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Custom Citation Hein, Carola. "European Spatial Development, the Polycentric EU Capital, and Eastern Enlargement." Comparative European Politics 4 (2006): 253-271. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/cities_pubs/24 For more information, please contact [email protected]. European Spatial Development, the Polycentric EU Capital, and Eastern Enlargement Article submitted for publication in a special issue of Comparative European Politics on ‘Rethinking European Spaces’ to appear as volume 4, number 2, July 2006 Carola Hein Growth and Structure of Cities Program Bryn Mawr College 101 N. Merion Bryn Mawr PA 19010-2899 USA [email protected] Keywords : polycentricity; urban planning; capital cities; European Union; Tallinn; Warsaw; Budapest. Abstract: Over five decades a new decentralized model for the European capital city has emerged through the distribution of European Union (EU) institutions and agencies, but as the result of national compromise and competition rather than the implementation of a vision of Europe. More than a purely administrative issue, the location of EU headquarters opens questions on the nature of European spatiality, the relation between politics and space and the role of headquarters cities in that space. -

Copenhagen Guide Copenhagen Guide Money

COPENHAGEN GUIDE COPENHAGEN GUIDE MONEY Currency: Danish Krone (DKK), 1 Krone = 100 øre. Hostels (average price/night) – 160 DKK Essential Information 4* hotel (average price/night) – 1200 DKK Money 3 Money exchange is easy in Denmark as there Car-hire (medium-sized car/day) – 680 DKK are many banks and exchange kiosks. The ser- The museums and main sights typically cost 20 to Communication 4 The capital of Denmark stretches its charming vice fees are quite high, though. Generally, it is 80 DKK, half-price for children. Students with ISIC center over two islands. Don’t be put off by its cheaper to withdraw money from an ATM – they are eligible to discounts of anything between 20% Holidays 5 small size – it offers an amazing array of oppor- are plentiful. and 50%. Transportation 6 tunities for an unforgettable stay. It is a ma- jor cultural hub and home to countless royal, Visa and Master Card are widely accepted in Den- Tipping Food 8 state and private museums and galleries that mark with one exception; supermarkets usually Service charges are included in the bill. If you present mind-blowing exhibits, artworks and accept only Danish cards – best to check the stick- have been really satisfied with the service, round- Events During The Year 9 collections. You can also marvel at its magnifi- ers on the door when entering. ing up the bill is always appreciated. cent historical buildings in New Port or Strædet 10 Things to do as well as modern architectural gems. When Tax Refunds tired of the city, you can easily find peace in its DOs and DO NOTs 11 The VAT is 25% and is refundable to non-EU resi- vast parks or in the surrounding picturesque dents. -

'Faces' of the European Metropolis and Their Greek Version

B. Ioannou & K. Serraos, Int. J. Sus. Dev. Plann. Vol. 2, No. 2 (2007) 205–221 THE NEW ‘FACES’ OF THE EUROPEAN METROPOLIS AND THEIR GREEK VERSION B. IOANNOU & K. SERRAOS School of Architecture, National Technical University of Athens, Athens, Greece. ABSTRACT The aim of this study is to present significant ‘faces’ characterizing the physiognomy of the contemporary Greek city as it is shaped or being shaped at the moment. In this context, the term ‘city face’ is used as an analytic tool, acknowledging that the image of the city is nothing less than the material and concrete expression of the really complicated, immaterial urban dynamics and trends. The main argument is whether the diverse ‘faces’ of the European metropolis are reproduced in the Greek city as well, simultaneously or with a delay; and whether the Greek city follows its own particular evolution, presenting similarities or differences from the European case. At a first step, corresponding views or aspects of urban image at the European or the global level are presented to create a wider reference framework. The European city ‘faces’ considered in this study are: gentrified city, multicultural city, sustainable city, virtual city, and the city of a special identity. The second step is to define dominant urban ‘faces’ for the Greek city as well: the historic city, the planned and designed city, the unplanned/ arbitrary city, the rural city, the marginalized city, the natural city, and the globalized city. Our analysis, summarizing the conclusions of recent research and studies, has shown that the revealed new ‘faces’ of the Greek city, although a result of widespread external dynamics, correspond to more or less common aspects of urban evolution; in fact, they are motivated by different agents and conditions in the Greek paradigm than in the European one. -

Cities Are Back in Town: the US/Europe Comparison

Cahier Européen numéro 05/06 du Pôle Ville/métropolis/cosmopolis Centre d’Etudes Européennes de Sciences Po (Paris) Cities are back in town: the US/Europe comparison Par Patrick Le Galès Directeur de Recherche, CNRS, CEVIPOF and Mathieu Zagrodzki Doctorant, politique publique, CEVIPOF, Sciences Po From the integrated medieval European cities surrounded by walls, to the colonial Boston or the rapidly growing Phoenix, Las Vegas, or London South East, the category “city” comprises different density, borders and dimensions for instance : the material city of walls, squares, houses, roads, light, utilities, buildings, waste, and physical infrastructure ; the cultural city in terms of imaginations, differences, representations, ideas, symbols, arts, texts, senses, religion, aesthetics, the politics and policies of the city in terms of domination, power, government, mobilisation, welfare, education ; the social city of riots, ethnic, economic or gender inequalities, everyday life and social movements ; the economy of the city : division of labour, scale, production, consumption, trade..... Urban areas are robust beasts. Despite ups and downs, contrasting evolution over time, most of them have considerable amount of resources which have been accumulated and which, in due course, may be mobilised for new period of growth. This does not exclude period or sequences of rapid changes, but not so often. Comparing US and European cities is a classic exercise of urban sociology. Urban sociology has long privileged analytical models of the convergence of cities, either based on models of urban ecology 1 inspired by writers from the University of Chicago, or in the context of the Marxist and neo-Marxist tradition that privileges the decisive influence of uneven development, and capitalism on social structures, modes of government, and urban policies. -

Co Washington 0250O 11363.Pdf (14.78Mb)

The Urban (in)Formal Reinterpreting the Globalized City through Deleuze and Guattari Allan Villanueva Co A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Architecture History and Theory University of Washington 2012 Committee: Brian L. McLaren Mark Purcell Program authorized to offer degree: College of Built Environments, Department of Architecture ©Copyright 2012 Allan Villanueva Co University of Washington Abstract The Urban (in)Formal Reinterpreting the Globalized City through Deleuze and Guattari Allan Villanueva Co | i Chair of Supervisory Committee Associate Professor Brian L McLaren, PhD This thesis provides a new definition of globalization within the social and spatial terrains of cities, one that is intricately linked to the growth of “informal urbanism,” sub-market economies and the ad-hoc construction of slums. It argues that informality is not anomalous to the otherwise homogenized image of the contemporary global city, but rather forms a crucial part of an urban terrain created from a configuration of opposing forces, the formal and the informal, which are in a constant state of exchange. In support of these arguments, this thesis draws upon Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus. The theoretical source is crucial as it offers an interpreta- tion of the city as an assemblage of disparate pieces, their relationships being a negotiation of “the smooth and the striated,” the whole being a body like the “rhizome.” These theorists supply this thesis’ vocabulary and conceptualization, used as new tools for interpretation and description. This thesis then uses multi-scalar case studies informed by these writings in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil and Caracas, Venezuela, to reinterpret the globalized city. -

14Th IATSO Conference

General Information 14th IATSO Conference September 07-10th 2016 in Copenhagen General Information Table of Contents 1) Arriving in Copenhagen .................................................................................................. 2 2) How to get to the City Center.......................................................................................... 2 3) Conference Venue ......................................................................................................... 3 4) City Hall Reception ......................................................................................................... 4 5) Conference Dinner ......................................................................................................... 5 6) Leisure Activities - Copenhagen (Places to Visit) ........................................................... 6 1 General Information 1) Arriving in Copenhagen You will arrive at Copenhagen Airport, Kastrup – CPH (in Danish: Københavns Lufthavn, Kastrup) 2) How to get to the City Center 2.1. Option A) Subway If you take the “yellow line”, it only takes around 25 minutes to get to the central station. Nørreport station is Copenhagens traffic nerve center. From there, you can take buses, trains and metro to almost everywhere. For more information, please also see Map 1! Map 1: Subway Map 2 General Information 2.2. Option B) Train There is also the possibility to take a train to the city center which takes around 30 minutes. However, trains run less frequently than the subway. Tickets for public