Viennese Planning Culture: Understanding Change and Continuity Through the Hauptbahnhof

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Vienna Children and Youth Strategy 2020 – 2025 Publishing Details Editorial

The Vienna Children and Youth Strategy 2020 – 2025 Publishing Details Editorial Owner and publisher: In 2019, the City of Vienna introduced in society. Thus, their feedback was Vienna City Administration the Werkstadt Junges Wien project, a taken very seriously and provided the unique large-scale participation pro- basis for the definition of nine goals Project coordinators: cess to develop a strategy for children under the Children and Youth Stra- Bettina Schwarzmayr and Alexandra Beweis and young people with the aim of tegy. Now, Vienna is for the first time Management team of the Werkstadt Junges Wien project at the Municipal Department for Education and Youth giving more room to the requirements bundling efforts from all policy areas, in cooperation with wienXtra, a young city programme promoting children, young people and families of Vienna’s young residents. The departments and enterprises of the “assignment” given to the children city and is aligning them behind the Contents: and young people participating in shared vision of making the City of The contents were drafted on the basis of the wishes, ideas and concerns of more than 22,500 children and young the project was to perform a “service Vienna a better place for all children people in consultation with staff of the Vienna City Administration, its associated organisations and enterprises check” on the City of Vienna: What and young people who live in the city. and other experts as members of the theme management groups in the period from April 2019 to December 2019; is working well? What is not working responsible for the content: Karl Ceplak, Head of Youth Department of the Province of Vienna well? Which improvements do they The following strategic plan presents suggest? The young participants were the results of the Werkstadt Junges Design and layout: entirely free to choose the issues they Wien project and outlines the goals Die Mühle - Visual Studio wanted to address. -

Introduction Podge of Half-Anonymous Nationalities and Clumsily Struggling Against the Fresh, Ambitious, and Apparently Victorious Idea of Nationalism

IN TRODUCTION ustria-Hungary ceased to exist almost a hundred years ago. The A oldest generation of Central Europeans can remember it from their parents’ and grandparents’ stories. The majority of them learned about it in high school and associates the monarchy with its few roy- als, particularly the late Franz Joseph and his eccentric wife Elisabeth. Those figures, already famous during their lifetime, entered the realm of popular culture and remain recognizable in most countries of Eu- rope, providing a stable income for the souvenir industry in what used to be their empire and inspiration for screenwriters on both sides of the Atlantic. Naturally, the situation varies from country to country as far as history textbooks and historical monuments are concerned. Thus, Austrians and Hungarians are generally more familiar with the monarchy than are the Germans or Poles, not to mention the British and French, whereas Serbs, Italians, Czechs, and Romanians tend to be highly suspicious of it. The old monarchy also built quite well, so modern travelers who wish to see what is left of the Habsburg em- pire do not need to limit their curiosity to imperial residences, nor to the opera houses in cities such as Prague, Lviv, and Zagreb. In most cities of former Austria-Hungary, visitors can get acquainted with Habsburg architecture at the railway station. In this respect Vienna, heavily bombed by the Anglo-American air forces and the Soviet artil- lery during World War II, is merely a sad exception. Other traces of the 1 imperial past can still be discovered in many private apartments, an- tique shops, and retro-style cafés, in cemeteries, and old photographs. -

Sources for Genealogical Research at the Austrian War Archives in Vienna (Kriegsarchiv Wien)

SOURCES FOR GENEALOGICAL RESEARCH AT THE AUSTRIAN WAR ARCHIVES IN VIENNA (KRIEGSARCHIV WIEN) by Christoph Tepperberg Director of the Kriegsarchiv 1 Table of contents 1. The Vienna War Archives and its relevance for genealogical research 1.1. A short history of the War Archives 1.2. Conditions for doing genealogical research at the Kriegsarchiv 2. Sources for genealogical research at the Kriegsarchiv 2. 1. Documents of the military administration and commands 2. 2. Personnel records, and records pertaining to personnel 2.2.1. Sources for research on military personnel of all ranks 2.2.2. Sources for research on commissioned officers and military officials 3. Using the Archives 3.1. Regulations for using personnel records 3.2. Visiting the Archives 3.3. Written inquiries 3.4. Professional researchers 4. Relevant publications 5. Sources for genealogical research in other archives and institutions 5.1. Sources for genealogical research in other departments of the Austrian State Archives 5.2. Sources for genealogical research in other Austrian archives 5.3. Sources for genealogical research in archives outside of Austria 5.3.1. The provinces of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and its “successor states” 5.3.2. Sources for genealogical research in the “successor states” 5.4. Additional points of contact and practical hints for genealogical research 2 1. The Vienna War Archives and its relevance for genealogical research 1.1. A short history of the War Archives Today’s Austrian Republic is a small country, but from 1526 to 1918 Austria was a great power, we can say: the United States of Middle and Southeastern Europe. -

The Empire in the Provinces: the Case of Carinthia

religions Article The Empire in the Provinces: The Case of Carinthia Helmut Konrad Institut für Geschichte, Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz, Attemsgasse 8/II, [505] 8010 Graz, Austria; [email protected] Academic Editors: Malachi Hacohen and Peter Iver Kaufman Received: 16 May 2016; Accepted: 1 August 2016; Published: 5 August 2016 Abstract: This article examines the legacy of the Habsburg Monarchy in the First Austrian Republic, both in the capital, Vienna, and in the province of Carinthia. It concludes that Social Democracy, often cited as one of the six ingredients that held the old Empire together, took on distinct forms in the Republic’s different federal states. The scholarly literature on the post-1918 “heritage” of the Monarchy therefore needs to move beyond monolithic generalizations and toward regionally focused comparative studies. Keywords: empire; socialism; Jews; Habsburg Monarchy; Austria; Vienna; Carinthia; German Nationalism; Sprachenkampf 1. Introduction Which forms did the ideas take that allowed the Habsburg monarchy to persist, despite the diversity of nationalisms present in the small Republic of German-Austria, for so long after the end of the First World War? What was the “glue” that held this multiethnic empire together, when its collapse had been predicted since 1848, and which of its elements continued to exist beyond 1918? How was this heritage expressed in the different regions of the new republic? At least six factors can be identified as ingredients of the “glue” that held the monarchy together: first, the Emperor, a figure who symbolized the fusion of the complex linguistic, ethnic and religious components of the Habsburg state; second, the administrative officials, who were loyal to the Emperor and worked in the ubiquitous and even architecturally similar buildings of the Monarchy’s district authorities and train stations; third, the army, whose members promoted the imperial ideals through their long terms of service and acknowledged linguistic diversity. -

Footpath Description

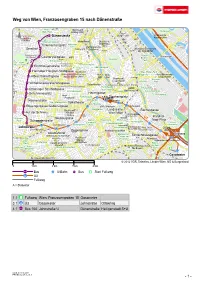

Weg von Wien, Franzosengraben 15 nach Dänenstraße N Hugo- Bezirksamt Wolf- Park Donaupark Döbling (XIX.) Lorenz- Ignaz- Semmelweis- BUS Dänenstraße Böhler- UKH Feuerwache Kaisermühlen Frauenklinik Fin.- BFI Fundamt BUS Türkenschanzpark Verkehrsamt Bezirksamt amt Brigittenau Türkenschanzplatz Währinger Lagerwiese Park Rettungswache (XX.) Gersthof BUS Finanzamt Brigittenau Pensionsversicherung Brigittenau der Angestellten Orthopädisches Rudolf- BUS Donauinsel Kh. Gersthof Czartoryskigasse WIFI Bednar- Währing Augarten Schubertpark Park Dr.- Josef- 10A Resch- Platz Evangelisches AlsergrundLichtensteinpark BUS Richthausenstraße Krankenhaus A.- Carlson- Wettsteinpark Anl. BUS Hernalser Hauptstr./Wattgasse Bezirksamt Max-Winter-Park Allgemeines Krankenhaus Verk.- Verm.- Venediger Au Hauptfeuerwache BUS Albrechtskreithgasse der Stadt Wien (AKH) Amt Amt Leopoldstadt W.- Leopoldstadt Hernals Bezirksamt Kössner- Leopoldstadt Volksprater Park BUS Wilhelminenstraße/Wattgasse (II.) Polizeidirektion Krankenhaus d. Barmherz. Brüder Confraternität-Privatklinik Josefstadt Rudolfsplatz DDSG Zirkuswiese BUS Ottakringer Str./Wattgasse Pass-Platz Ottakring Schönbornpark Rechnungshof Konstantinhügel BUS Schuhmeierplatz Herrengasse Josefstadt Arenawiese BUS Finanzamt Rathauspark U Stephansplatz Hasnerstraße Volksgarten WienU Finanzamt Jos.-Strauss-Park Volkstheater Heldenplatz U A BUS Possingergasse/Gablenzgasse U B.M.f. Finanzen U Arbeitsamt BezirksamtNeubau Burggarten Landstraße- Rochusgasse BUS Auf der Schmelz Mariahilf Wien Mitte / Neubau BezirksamtLandstraßeU -

Notes of Michael J. Zeps, SJ

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette History Faculty Research and Publications History Department 1-1-2011 Documents of Baudirektion Wien 1919-1941: Notes of Michael J. Zeps, S.J. Michael J. Zeps S.J. Marquette University, [email protected] Preface While doing research in Vienna for my dissertation on relations between Church and State in Austria between the wars I became intrigued by the outward appearance of the public housing projects put up by Red Vienna at the same time. They seemed to have a martial cast to them not at all restricted to the famous Karl-Marx-Hof so, against advice that I would find nothing, I decided to see what could be found in the archives of the Stadtbauamt to tie the architecture of the program to the civil war of 1934 when the structures became the principal focus of conflict. I found no direct tie anywhere in the documents but uncovered some circumstantial evidence that might be explored in the future. One reason for publishing these notes is to save researchers from the same dead end I ran into. This is not to say no evidence was ever present because there are many missing documents in the sequence which might turn up in the future—there is more than one complaint to be found about staff members taking documents and not returning them—and the socialists who controlled the records had an interest in denying any connection both before and after the civil war. Certain kinds of records are simply not there including assessments of personnel which are in the files of the Magistratsdirektion not accessible to the public and minutes of most meetings within the various Magistrats Abteilungen connected with the program. -

The Jewish Middle Class in Vienna in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries

The Jewish Middle Class in Vienna in the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries Erika Weinzierl Emeritus Professor of History University of Vienna Working Paper 01-1 October 2003 ©2003 by the Center for Austrian Studies (CAS). Permission to reproduce must generally be obtained from CAS. Copying is permitted in accordance with the fair use guidelines of the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976. CAS permits the following additional educational uses without permission or payment of fees: academic libraries may place copies of CAS Working Papers on reserve (in multiple photocopied or electronically retrievable form) for students enrolled in specific courses; teachers may reproduce or have reproduced multiple copies (in photocopied or electronic form) for students in their courses. Those wishing to reproduce CAS Working Papers for any other purpose (general distribution, advertising or promotion, creating new collective works, resale, etc.) must obtain permission from the Center for Austrian Studies, University of Minnesota, 314 Social Sciences Building, 267 19th Avenue S., Minneapolis MN 55455. Tel: 612-624-9811; fax: 612-626-9004; e-mail: [email protected] 1 Introduction: The Rise of the Viennese Jewish Middle Class The rapid burgeoning and advancement of the Jewish middle class in Vienna commenced with the achievement of fully equal civil and legal rights in the Fundamental Laws of December 1867 and the inter-confessional Settlement (Ausgleich) of 1868. It was the victory of liberalism and the constitutional state, a victory which had immediate and phenomenal demographic and social consequences. In 1857, Vienna had a total population of 287,824, of which 6,217 (2.16 per cent) were Jews. -

Step 2025 Urban Development Plan Vienna

STEP 2025 URBAN DEVELOPMENT PLAN VIENNA TRUE URBAN SPIRIT FOREWORD STEP 2025 Cities mean change, a constant willingness to face new develop- ments and to be open to innovative solutions. Yet urban planning also means to assume responsibility for coming generations, for the city of the future. At the moment, Vienna is one of the most rapidly growing metropolises in the German-speaking region, and we view this trend as an opportunity. More inhabitants in a city not only entail new challenges, but also greater creativity, more ideas, heightened development potentials. This enhances the importance of Vienna and its region in Central Europe and thus contributes to safeguarding the future of our city. In this context, the new Urban Development Plan STEP 2025 is an instrument that offers timely answers to the questions of our present. The document does not contain concrete indications of what projects will be built, and where, but offers up a vision of a future Vienna. Seen against the background of the city’s commit- ment to participatory urban development and urban planning, STEP 2025 has been formulated in a broad-based and intensive process of dialogue with politicians and administrators, scientists and business circles, citizens and interest groups. The objective is a city where people live because they enjoy it – not because they have to. In the spirit of Smart City Wien, the new Urban Development Plan STEP 2025 suggests foresighted, intelli- gent solutions for the future-oriented further development of our city. Michael Häupl Mayor Maria Vassilakou Deputy Mayor and Executive City Councillor for Urban Planning, Traffic &Transport, Climate Protection, Energy and Public Participation FOREWORD STEP 2025 In order to allow for high-quality urban development and to con- solidate Vienna’s position in the regional and international context, it is essential to formulate clearcut planning goals and to regu- larly evaluate the guidelines and strategies of the city. -

Building an Unwanted Nation: the Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository BUILDING AN UNWANTED NATION: THE ANGLO-AMERICAN PARTNERSHIP AND AUSTRIAN PROPONENTS OF A SEPARATE NATIONHOOD, 1918-1934 Kevin Mason A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Advisor: Dr. Christopher Browning Reader: Dr. Konrad Jarausch Reader: Dr. Lloyd Kramer Reader: Dr. Michael Hunt Reader: Dr. Terence McIntosh ©2007 Kevin Mason ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kevin Mason: Building an Unwanted Nation: The Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934 (Under the direction of Dr. Christopher Browning) This project focuses on American and British economic, diplomatic, and cultural ties with Austria, and particularly with internal proponents of Austrian independence. Primarily through loans to build up the economy and diplomatic pressure, the United States and Great Britain helped to maintain an independent Austrian state and prevent an Anschluss or union with Germany from 1918 to 1934. In addition, this study examines the minority of Austrians who opposed an Anschluss . The three main groups of Austrians that supported independence were the Christian Social Party, monarchists, and some industries and industrialists. These Austrian nationalists cooperated with the Americans and British in sustaining an unwilling Austrian nation. Ultimately, the global depression weakened American and British capacity to practice dollar and pound diplomacy, and the popular appeal of Hitler combined with Nazi Germany’s aggression led to the realization of the Anschluss . -

Demologos Case Study Centrope

Institut für Regional- und Umweltwirtschaft Institute of Regional Development and Environment Andreas Novy, Lukas Lengauer, Daniela Coimbra de Souza Vienna in an emerging trans-border region: Socioeconomic development in Central Europe SRE-Discussion 2008/08 2008 Vienna in an emerging trans-border region: Socioeconomic development in Central Europe NOVY, Andreas1 LENGAUER, Lukas1 COIMBRA DE SOUZA, Daniela1 Abstract: Drawing upon a periodisation of socio-economic development based on the regulation approach, the paper conducts a historical spatial development analysis of Vienna in its broader territory and multi-level perspective. The National context and the East-West cleavages mark the geography of the study. This periodisation is the basis to understand the strategies of Vienna in changing territorialities, the social forces and discourses that are reflected in the present context of Europeanisation, internationalisation and integration of border regions. A critical institutionalist approach is used to analyse the hegemonic liberal and populist discourses and strategies. The lessons taken in this section build the path to outline windows of opportunity for progressive politics, which are sketch out in the last section of the article. The ideas exposed in the paper are partial results of broader research carried out in the frame of DEMOLOGOS, an EU financed project. Key-Words: Socio-economic development; Vienna; progressive politics; Post-Fordism, democracy 1 Respectively Professor, Research Assistant and Research Assistant/ Ph.D. Candidate at: Institute for Regional Development and Environment; Vienna University for Economics and Business Administration. Address: Nordbergstraße 15 /B 4.06 (UZA4) - A-1090 Wien/ Vienna, Austria Tel.: +43-(0)1-31336-4777 Fax: +43-(0)1-31336-705 Email: [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected] 1 Introduction This case study analyses the spatial dimension of socioeconomic development in Vienna. -

European Spatial Development, the Polycentric EU Capital, and Eastern Enlargement Carola Hein Bryn Mawr College, [email protected]

Bryn Mawr College Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College Growth and Structure of Cities Faculty Research Growth and Structure of Cities and Scholarship 2006 European Spatial Development, the Polycentric EU Capital, and Eastern Enlargement Carola Hein Bryn Mawr College, [email protected] Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.brynmawr.edu/cities_pubs Part of the Architecture Commons, History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Custom Citation Hein, Carola. "European Spatial Development, the Polycentric EU Capital, and Eastern Enlargement." Comparative European Politics 4 (2006): 253-271. This paper is posted at Scholarship, Research, and Creative Work at Bryn Mawr College. http://repository.brynmawr.edu/cities_pubs/24 For more information, please contact [email protected]. European Spatial Development, the Polycentric EU Capital, and Eastern Enlargement Article submitted for publication in a special issue of Comparative European Politics on ‘Rethinking European Spaces’ to appear as volume 4, number 2, July 2006 Carola Hein Growth and Structure of Cities Program Bryn Mawr College 101 N. Merion Bryn Mawr PA 19010-2899 USA [email protected] Keywords : polycentricity; urban planning; capital cities; European Union; Tallinn; Warsaw; Budapest. Abstract: Over five decades a new decentralized model for the European capital city has emerged through the distribution of European Union (EU) institutions and agencies, but as the result of national compromise and competition rather than the implementation of a vision of Europe. More than a purely administrative issue, the location of EU headquarters opens questions on the nature of European spatiality, the relation between politics and space and the role of headquarters cities in that space. -

The German National Attack on the Czech Minority in Vienna, 1897

THE GERMAN NATIONAL ATTACK ON THE CZECH MINORITY IN VIENNA, 1897-1914, AS REFLECTED IN THE SATIRICAL JOURNAL Kikeriki, AND ITS ROLE AS A CENTRIFUGAL FORCE IN THE DISSOLUTION OF AUSTRIA-HUNGARY. Jeffery W. Beglaw B.A. Simon Fraser University 1996 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts In the Department of History O Jeffery Beglaw Simon Fraser University March 2004 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME: Jeffery Beglaw DEGREE: Master of Arts, History TITLE: 'The German National Attack on the Czech Minority in Vienna, 1897-1914, as Reflected in the Satirical Journal Kikeriki, and its Role as a Centrifugal Force in the Dissolution of Austria-Hungary.' EXAMINING COMMITTEE: Martin Kitchen Senior Supervisor Nadine Roth Supervisor Jerry Zaslove External Examiner Date Approved: . 11 Partial Copyright Licence The author, whose copyright is declared on the title page of this work, has granted to Simon Fraser University the right to lend this thesis, project or extended essay to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. The author has further agreed that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by either the author or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without the author's written permission.