Urban Development and Expressways in Tokyo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coastlines in Inoh's Map, 1821

International Journal of Geo-Information Article Geospatial Analysis of the Non-Surveyed (Estimated) Coastlines in Inoh’s Map, 1821 Yuki Iwai 1,2,* and Yuji Murayama 3 1 Graduate School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba 305-8572, Japan 2 JSPS Research Fellow, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, Chiyoda, Tokyo 102-8471, Japan 3 Faculty of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Tsukuba, Tsukuba 305-8572, Japan; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The history of modern maps in Japan began with Inoh’s map that was made by surveying the whole of Japan on foot 200 years ago. Inoh’s team investigated coastlines, major roads, and geographical features such as rivers, lakes, temples, forts, village names, etc. The survey was successively conducted ten times from 1800 to 1816. Inoh’s map is known as the first scientific map in Japan using a systematic method. However, the actual survey was conducted only for 75% of the coastlines in Japan and the remaining 25% was drawn by Inoh’s estimation (observation). This study investigated how the non-surveyed (estimated) coastlines were distributed in the map and why the actual survey was not conducted in these non-surveyed coastlines. Using GIS, we overlaid the geometrically corrected Inoh’s map (Digital Inoh’s Map Professional Edition) with the current map published by the Geospatial Information Authority (GSI) of Japan for examining the spatial difference. We found that the non-surveyed coastlines were in places where the practice of actual surveying was topographically difficult because of the limited surveying technology of those days. -

ZIPAIR's December 2020 to End of March 2021 Period Tokyo-Seoul

ZIPAIR’s December 2020 to end of March 2021 period Tokyo-Seoul and Tokyo-Bangkok routes booking is now open October 30, 2020 Tokyo, October 30, 2020 – ZIPAIR Tokyo will start to sell tickets for the Tokyo (Narita) - Seoul (Incheon) and Tokyo (Narita) - Bangkok (Suvarnabhumi) routes for travel between December 1, 2020 and March 27, 2021, from today, October 30. 1. Flight Schedule Tokyo (Narita) - Seoul (Incheon) (October 25 – March 26, 2021) Flight Route Schedule Operating day number Tokyo (Narita) = ZG 41 Narita (NRT) 8:40 a.m. Seoul (ICN) 11:15 a.m. Tue., Fri., Sun. Seoul (Incheon) ZG 42 Seoul (ICN) 12:40 p.m. Narita (NRT) 3:05 p.m. Tue., Fri., Sun. Bangkok (Suvarnabhumi) – Tokyo (Narita) “one-way” Service (October 28 – March 27, 2021) Flight Route Schedule Operating day number Bangkok This service is only available from Bangkok. (Suvarnabhumi) - ZG 52 Bangkok (BKK) 11:30 p.m. Wed., Thu., Fri., Tokyo (Narita) Narita (NRT) 7:15 a.m. (+1) Sat., Sun. 2. Sales Start Flights between December 1 and March 27, 2021. October 30, 6:00 p.m. Website:https://www.zipair.net 3. Airfares (1) Seat Fare (Tokyo - Seoul route) Fare (per seat, one-way) Fare Types Effective period Age Tokyo-Seoul Seoul-Tokyo ZIP Full-Flat JPY30,000-141,000 KRW360,000-440,000 7 years and older Standard Oct. 25, 2020 JPY8,000-30,000 KRW96,000-317,000 7 years and - Mar. 26, 2021 older U6 Standard JPY3,000 KRW36,000 Less than 7 years (2) Seat Fare (Tokyo - Bangkok route) Fare (per seat, one-way) Fare Types Effective period Age Tokyo-Bangkok Bangkok-Tokyo ZIP Full-Flat THB15,000-61,800 7 years and Value older Standard Oct. -

Geography & Climate

Web Japan http://web-japan.org/ GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE A country of diverse topography and climate characterized by peninsulas and inlets and Geography offshore islands (like the Goto archipelago and the islands of Tsushima and Iki, which are part of that prefecture). There are also A Pacific Island Country accidented areas of the coast with many Japan is an island country forming an arc in inlets and steep cliffs caused by the the Pacific Ocean to the east of the Asian submersion of part of the former coastline due continent. The land comprises four large to changes in the Earth’s crust. islands named (in decreasing order of size) A warm ocean current known as the Honshu, Hokkaido, Kyushu, and Shikoku, Kuroshio (or Japan Current) flows together with many smaller islands. The northeastward along the southern part of the Pacific Ocean lies to the east while the Sea of Japanese archipelago, and a branch of it, Japan and the East China Sea separate known as the Tsushima Current, flows into Japan from the Asian continent. the Sea of Japan along the west side of the In terms of latitude, Japan coincides country. From the north, a cold current known approximately with the Mediterranean Sea as the Oyashio (or Chishima Current) flows and with the city of Los Angeles in North south along Japan’s east coast, and a branch America. Paris and London have latitudes of it, called the Liman Current, enters the Sea somewhat to the north of the northern tip of of Japan from the north. The mixing of these Hokkaido. -

Rapid Range Expansion of the Feral Raccoon (Procyon Lotor) in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan, and Its Impact on Native Organisms

Rapid range expansion of the feral raccoon (Procyon lotor) in Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan, and its impact on native organisms Hisayo Hayama, Masato Kaneda, and Mayuh Tabata Kanagawa Wildlife Support Network, Raccoon Project. 1-10-11-2 Takamoridai, Isehara 259-1115, Kanagawa, Japan Abstract The distribution of feral raccoons (Procyon lotor) was surveyed in Kanagawa Prefecture, central Japan. Information was collected mainly through use of a questionnaire to municipal offices, environment NGOs, and hunting specialists. The raccoon occupied 26.5% of the area of the prefecture, and its distribution range doubled over three years (2001 to 2003). The most remarkable change was the range expansion of the major population in the south-eastern part of the prefecture, and several small populations that were found throughout the prefecture. Predation by feral raccoons on various native species probably included endangered Tokyo salamanders (Hynobius tokyoensis), a freshwater Asian clam (Corbicula leana), and two large crabs (Helice tridens and Holometopus haematocheir). The impact on native species is likely to be more than negligible. Keywords: Feral raccoon; Procyon lotor; distribution; questionnaire; invasive alien species; native species; Kanagawa Prefecture INTRODUCTION The first record of reproduction of the feral raccoon presence of feral raccoons between 2001 and 2003 in Kanagawa Prefecture was from July 1990, and it and the reliability of the information. One of the was assumed that the raccoon became naturalised in issues relating to reliability is possible confusion with this prefecture around 1988 (Nakamura 1991). the native raccoon dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides; Damage by feral raccoons is increasing and the Canidae), which has a similar facial pattern with a number of raccoons, captured as part of the wildlife black band around the eyes, and a similar body size to pest control programme, is also rapidly increasing. -

NII Start Operation 400 Gbps Tokyo-Osaka Link to Speed Up

NEWS RELEASE December 6, 2019 NII start operation 400 Gbps Tokyo-Osaka link to speed up SINET, ultra-high speed network supporting Japan’s academic research: Putting world-leading long-distance 400 Gbps link into practical operation The National Institute of Informatics (NII, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan; Dr. Masaru KITSUREGAWA, Director General) has constructed a long-distance link with a world’s top-class transmission speed of 400 Gbps between Tokyo and Osaka as part of an academic information network, SINET5(*1). The existing SINET5 provides 100 Gbps links covering all of Japan’s prefectures. The new link has a capacity four times that of existing links. It will come into service on December 9. The purpose of constructing this 400 Gbps link is to increase the transmission capacity between the Kanto area centering on Tokyo and the Kansai area centering on Osaka and thereby to resolve the tight capacity situation amid soaring demand for data communication between the two regions where universities, research organizations, and other entities are concentrated. This implementation removes the issue about network resources being occupied by high-volume data communication and ensures stable communication. The updated infrastructure meets demands for further data increases and new high-volume data transmissions in inter-university collaborations and large research projects. Figure: General view of SINET5, in which a 400-Gbps link (shown as a red line) has been added between Tokyo and Osaka Research Organization of Information and Systems National Institute for Informatics Web: https://www.nii.ac.jp Publicity Team 2-1-2 Hitotsubashi, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo Twitter: @jouhouken 101-8430 JAPAN facebook: https://www.facebook.com/jouhouken Direct: +81(0)3-4212-2164 FAX:+81(0)3-4212-2150 E-Mail: [email protected] SINET is a network utilized by universities and research organizations across Japan. -

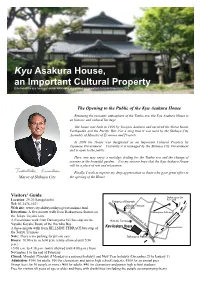

Kyu Asakura House,An Important Cultural Property

Kyu Asakura House, an Important Cultural Property Exterior of the kyu Asakura House, which was designated an Important Cultural Property in 2004 The Opening to the Public of the Kyu Asakura House Retaining the romantic atmosphere of the Taisho era, the Kyu Asakura House is an historic and cultural heritage. The house was built in 1919 by Torajiro Asakura and survived the Great Kanto Earthquake and the Pacific War. For a long time it was used by the Shibuya City Assembly of Ministry of Economy and Projects.. In 2004 the House was designated as an Important Cultural Property by Japanese Government. Currently it is managed by the Shibuya City Government and is open to the public. Here, one may enjoy a nostalgic feeling for the Taisho era and the change of seasons in the beautiful garden. It is my sincere hope that the Kyu Asakura House will be a place of rest and relaxation. Finally, I wish to express my deep appreciation to those who gave great effort to Mayor of Shibuya City the opening of the House. Visitors’ Guide Location: 29-20 Sarugakucho Tel: 03-3476-1021 Web site: www.city.shibuya.tokyo.jp/est/asakura.html Directions: A five-minute walk from Daikanyama Station on the Tokyu Toyoko Line A five-minute walk from Daikanyama Eki bus stop on the Yuyake Koyake Route of the Hachiko Bus A three-minute walk from HILLSIDE TERRACE bus stop of the Tokyu Transsés Note: There is no parking for private cars. Hours: 10:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. -

Saitama Prefecture Kanagawa Prefecture Tokyo Bay Chiba

Nariki-Gawa Notake-Gawa Kurosawa-Gawa Denu-Gawa Nippara-Gawa Kitaosoki-Gawa Saitama Prefecture Yanase-Gawa Shinshiba-Gawa Gake-Gawa Ohba-Gawa Tama-Gawa Yana-Gawa Kasumi-Gawa Negabu-Gawa Kenaga-Gawa Hanahata-Gawa Mizumotokoaitame Tamanouchi-Gawa Tobisu-Gawa Shingashi-Gawa Kitaokuno-Gawa Kita-Gawa Onita-Gawa Kurome-Gawa Ara-Kawa Ayase-Gawa Chiba Prefecture Lake Okutama Narahashi-Gawa Shirako-Gawa Shakujii-Gawa Edo-Gawa Yozawa-Gawa Koi-Kawa Hisawa-Gawa Sumida-Gawa Naka-Gawa Kosuge-Gawa Nakano-Sawa Hirai-Gawa Karabori-Gawa Ochiai-Gawa Ekoda-Gawa Myoushoji-Gawa KItaaki-Kawa Kanda-Gawa Shin-Naka-Gawa Zanbori-Gawa Sen-Kawa Zenpukuji-Gawa Kawaguchi-Gawa Yaji-Gawa Tama-Gawa Koto Yamairi-Gawa Kanda-Gawa Aki-Kawa No-Gawa Nihonbashi-Gawa Inner River Ozu-Gawa Shin-Kawa Daigo-Gawa Ne-Gawa Shibuya-Gawa Kamejima-Gawa Osawa-Gawa Iruma-Gawa Furu-Kawa Kyu-Edo-Gawa Asa-Kawa Shiroyama-Gawa Asa-Gawa Nagatoro-Gawa Kitazawa-Gawa Tsukiji-Gawa Goreiya-Gawa Yamada-Gawa Karasuyama-Gawa Shiodome-Gawa Hodokubo-Gawa Misawa-Gawa Diversion Channel Minami-Asa-Gawa Omaruyato-Gawa Yazawa-Gawa Jukuzure-Gawa Meguro-Gawa Yudono-Gawa Oguri-Gawa Hyoe-Gawa Kotta-Gawa Misawa-Gawa Annai-Gawa Kuhonbutsu-Gawa Tachiai-Gawa Ota-Gawa Shinkoji-Gawa Maruko-Gawa Sakai-Gawa Uchi-Kawa Tokyo Bay Tsurumi-Gawa Aso-Gawa Nomi-Kawa Onda-Gawa Legend Class 1 river Ebitori-Gawa Managed by the minister of land, Kanagawa Prefecture infrastructure, transport and tourism Class 2 river Tama-Gawa Boundary between the ward area and Tama area Secondary river. -

Chugoku・Shikoku Japan

in CHUGOKU・SHIKOKU JAPAN A map introducing facilities related to food and agriculture in the Chugoku-Shikoku Tottori Shimane Eat Okayama Hiroshima Yamaguchi Stay Kagawa Tokushima Ehime Kochi Experience Rice cake making Sightseeing Rice -planting 疏水のある風景写真コンテスト2010 Soba making 入選作品 題名「春うらら」 第13回しまねの農村景観フォトコンテスト入賞作品 第19回しまねの農村景観フォトコンテスト入賞作品 Chugoku-shikoku Regional Agricultural Administration Office Oki 26 【Chugoku Region】 7 13 9 8 Tottori sand dunes 5 3 1 Bullet train 14 2 25 4 16 17 11 Tottori Railway 36 15 12 6 Izumo Taisha 41 Matsue Tottori Pref. Shrine 18 Kurayoshi Expressway 37 10 Shimane Pref. 47 24 45 27 31 22 42 43 35 19 55 28 Iwami Silver Mine 48 38 50 44 29 33 34 32 30 Okayama Pref. 39 23 20 54 53 46 40 49 57 Okayama 21 Okayama 52 51 Kurashiki Korakuen 59 Hiroshima Pref. 60 64 79 75 76 80 62 Hiroshima Fukuyama Hagi 61 58 67 56 Atom Bomb Dome Great Seto Bridge 74 Yamaguchi Pref.Yamaguchi Kagawa Pref. 77 63 Miyajima Kintaikyo 68 69 Bridge Tokushima Pref. Shimonoseki 66 65 72 73 Ehime Pref. 70 71 78 Tottori Prefecture No. Facility Item Operating hours Address Phone number・URL Supported (operation period) Access language Tourism farms 1206Yuyama,Fukube-cho,Tottori city Phone :0857-75-2175 Mikaen Pear picking No holiday during 1 English 味果園 (Aug.1- early Nov.) the period. 20 min by taxi from JR Tottori Station on the Sanin http://www.mikaen.jp/ main line 1074-1Hara,Yurihama Town,Tohaku-gun Phone :0858-34-2064 KOBAYASHI FARM Strawberry picking 8:00~ 2 English 小林農園 (early Mar.- late Jun.) Irregular holidays. -

Face Express, a New Facial Recognition Technology for Boarding Procedures at NRT and HND Is Coming Soon ! It’S Seamless and Contactless Experience !

NEWS RELEASE 25 March 2021 Face Express, a new facial recognition technology for boarding procedures at NRT and HND is coming soon ! It’s seamless and contactless experience ! The operating companies of Narita International Airport (Narita International Airport Corporation - NAA) and Tokyo International Airport (Tokyo International Air Terminal Corporation - TIAT), will commence their trial for "Face Express”, a new boarding procedure using facial recognition technology, in April 2021. Once passengers register their facial image in Face Express, they will be able to access and proceed through subsequent procedures at the airport (check-in, baggage drop, security checkpoint entrance, boarding gate, etc.) without showing their passport and boarding pass. Its introduction will expedite seamless boarding procedures and, because most processing is touchless, it will also reduce the infection risks posed by person-to- person contact. The two airports will each commence their trial operation as below and prepare for a full launch in July. Start of trial operation : Tuesday, 13 April 2021 Participating airlines: All Nippon Airways, Japan Airlines (more airlines will participate later) Locations : [South Wing Terminal 1] Check-in Island C / Gates 51 to 57A [ Terminal 2 ]Check-in Island K / Gates 61 to 66, 71, 81 to 83, 91 to 93 • Service details are available at the following URL: https://www.narita-airport.jp/en/faceexpress/ Start of trial operation : Tuesday, 13 April 2021 Participating airlines: Airlines operating international flights at HND Locations: [Terminal 3] Check-in Islands D, E, G, H, I, J / All gates [Terminal 2*] Check-in Islands P, Q, T / All gates *All international counters are closed at present. -

Shikoku Access Map Matsuyama City & Tobe Town Area

Yoshikawa Interchange Hiroshima Airport Okayama Airport Okayama Kobe Suita Sanyo Expressway Kurashiki Junction Interchange Miki Junction Junction Junction Shikoku Himeji Tarumi Junction Itami Airport Hiroshima Nishiseto-Onomichi Sanyo Shinkansen Okayama Hinase Port Shin-Kobe Shin- Okayama Interchange Himeji Port Osaka Hiroshima Port Kure Port Port Obe Kobe Shinko Pier Uno Port Shodoshima Kaido Shimanami Port Tonosho Rural Experience Content Access Let's go Seto Ohashi Fukuda Port all the way for Port an exclusive (the Great Seto Bridge) Kusakabe Port Akashi Taka Ikeda Port experience! matsu Ohashi Shikoku, the journey with in. Port Sakate Port Matsubara Takamatsu Map Tadotsu Junction Imabari Kagawa Sakaide Takamatsu Prefecture Kansai International Imabari Junction Chuo Airport Matsuyama Sightseeing Port Iyosaijyo Interchange Interchange Niihama Awajishima Beppu Beppu Port Matsuyama Takamatsu Airport 11 11 Matsuyama Kawanoe Junction Saganoseki Port Tokushima Wakayama Oita Airport Matsuyama Iyo Komatsu Kawanoe Higashi Prefecture Naruto Interchange Misaki Interchange Junction Ikawa Ikeda Interchange Usuki Yawata Junction Wakimachi Wakayama Usuki Port Interchange hama Interchange Naruto Port Port Ozu Interchange Ehime Tokushima Prefecture Awa-Ikeda Tokushima Airport Saiki Yawatahama Port 33 32 Tokushima Port Saiki Port Uwajima Kochi 195 Interchange Hiwasa What Fun! Tsushima Iwamatsu Kubokawa Kochi Gomen Interchange Kochi Prefecture 56 Wakai Kanoura ■Legend Kochi Ryoma Shimantocho-Chuo 55 Airport Sukumo Interchange JR lines Sukumo Port Nakamura -

Pilgrimage to the 88 Temples of Shikoku Island: a Bibliography of Resources in English

Pilgrimage to the 88 Temples of Shikoku Island: A Bibliography of Resources in English Naomi Zimmer LIS 705, Fall 2005 The most widely known work in English about the Shikoku pilgrimage is undoubtedly Oliver Statler’s 1983 book Japanese Pilgrimage , which combines a personal account of Statler’s pilgrimage in Shikoku with substantial background and cultural information on the topic. The University of Hawaii’s Hamilton Library Japan Collection houses Statler’s personal papers in the Oliver Statler Collection , which includes several boxes of material related to the Shikoku pilgrimage. The Oliver Statler Collection is an unparalleled and one of a kind source of information in English on the Shikoku pilgrimage. The contents range from Statler’s detailed notes on each of the 88 temples to the original manuscript of Japanese Pilgrimage . Also included in the collection are several hand-written translations of previous works on the pilgrimage that were originally published in Japanese or languages other than English. The Oliver Statler Collection may be the only existing English translations of many of these works, as they were never published in English. The Collection also contains several photo albums documenting Statler’s pilgrimages on Shikoku taken between 1968 and 1979. A Pilgrimage to the 88 Temples in Shikoku Island (1973) is likely the earliest example of an English-language monograph on the specific topic of the Shikoku pilgrimage. This book, written by the Japanese author Mayumi Banzai, focuses on the legendary priest Kobo Daishi (774-835 A.D.) and the details of his association with the Shikoku pilgrimage. The books A Henro Pilgrimage Guide to the Eighty-eight Temples on Shikoku, Japan (Taisen Miyata), Echoes of Incense: a Pilgrimage in Japan (Don Weiss), The Traveler's Guide to Japanese Pilgrimages (Ed Readicker-Henderson), and Tales of a Summer Henro (Craig McLachlan) are all more recent personal accounts offering a less scholarly and more practical “guidebook” look at the pilgrimage. -

Regressive Femininity in American J-Horror Remakes

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2015 Lost in Translation: Regressive Femininity in American J-Horror Remakes Matthew Ducca Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/912 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] LOST IN TRANSLATION: REGRESSIVE FEMININITY IN AMERICAN J-HORROR REMAKES by Matthew Ducca A master’s thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, The City University of New York 2015 © 2015 MATTHEW J. DUCCA All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Liberal Studies in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Master of Arts. Professor Edward P. Miller__________________________ _____________________ _______________________________________________ Date Thesis Advisor Professor Matthew K. Gold_________________________ ______________________ _______________________________________________ Date Executive Officer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract Lost in Translation: Regressive Femininity in American J-Horror Remakes by Matthew Ducca Advisor: Professor Edward Miller This thesis examines the ways in which the representation of female characters changes between Japanese horror films and the subsequent American remakes. The success of Gore Verbinski’s The Ring (2002) sparked a mass American interest in Japan’s contemporary horror cinema, resulting in a myriad of remakes to saturate the market.