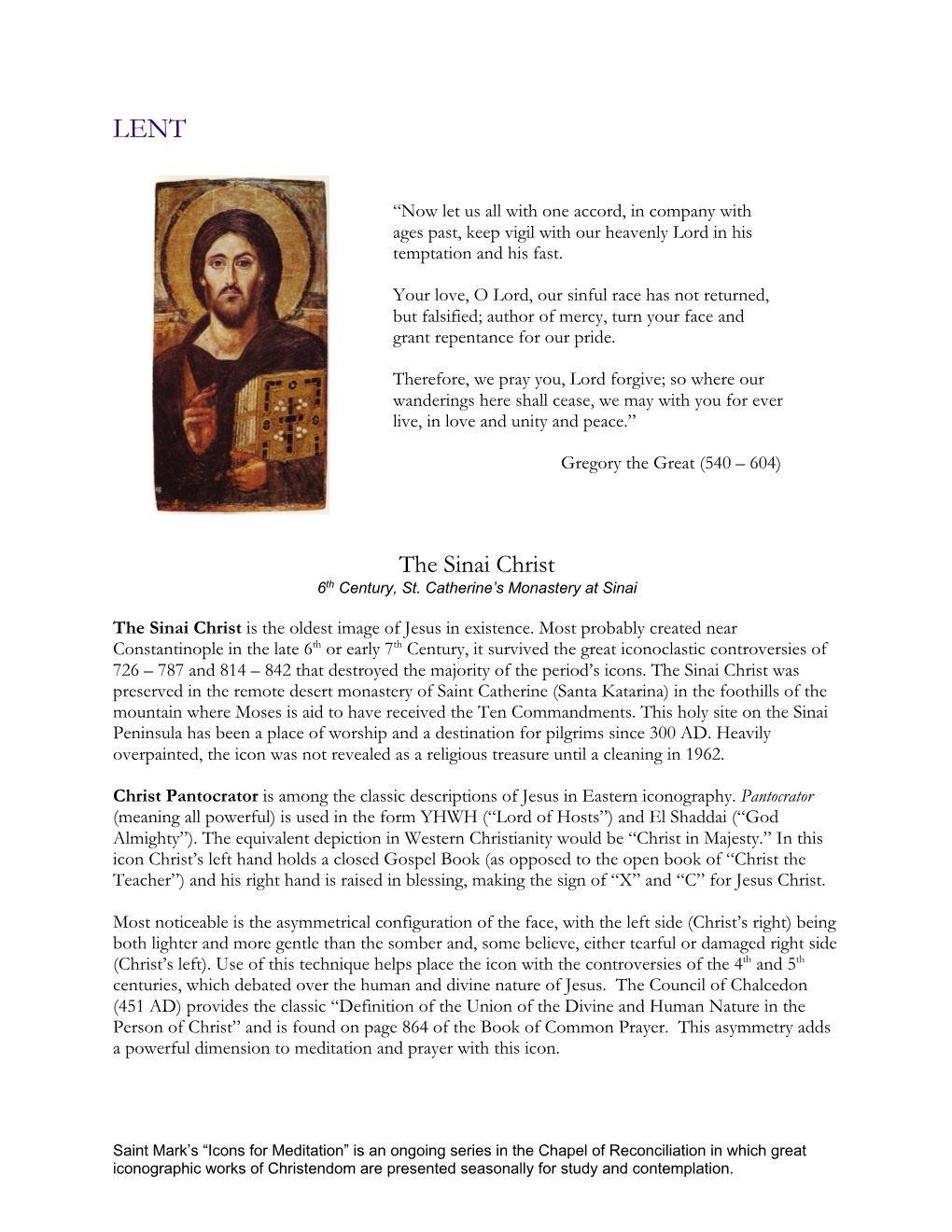

The Sinai Christ 6Th Century, St

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For the Bulletin of January21, 2018 the THIRD SUNDAY in WINTER's

For The Bulletin Of The sons of Zebedee are critical figures January21, 2018 in the Synoptic stories as opposed to the Gospel of John. In fact, we only hear of the “sons of Zebedee” in the epilogue of the Gospel of John, but nowhere in the first twenty chapters. Even in John 21 we don’t learn their names. They are merely the sons of Zebedee. But the image Mark paints for us is different. He gives us their names and depicts them as giving themselves in complete dedication to following Jesus. THE THIRD SUNDAY IN All is abandoned in their pursuit of him. WINTER’S ORDINARY TIME In this story we also hear something of the preaching of Jesus, which to a certain From Father Robert degree echoed that of John the Baptist. Cycle B of the Lectionary means we are Jesus’ preaching will be developed and reading primarily from the Gospel of expanded throughout the Gospel of Mark, even though last week we read Mark, but at this early stage it is from the Gospel of John, and heard centered around the twofold command, about the call of the first disciples, “Repent, and believe.” Andrew, and an unnamed disciple. This week we have a different version, The story is certainly idealized for Mark’s version, of the call of the first dramatic effect; we only need to look at disciples. Though Andrew is still part of the Gospel of John to see another the story, we do not have the “unnamed version of Andrew and Peter being disciple” from the Gospel of John. -

Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God George Contis M.D

University of Dayton eCommons Marian Library Art Exhibit Guides Spirituality through Art 2015 Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God George Contis M.D. Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.udayton.edu/ml_exhibitguides Recommended Citation Contis, George M.D., "Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God" (2015). Marian Library Art Exhibit Guides. 5. https://ecommons.udayton.edu/ml_exhibitguides/5 This Exhibit Guide is brought to you for free and open access by the Spirituality through Art at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marian Library Art Exhibit Guides by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God by George Contis, M.D., M.P.H . Russian Christian Orthodox Icons of the Mother of God by George Contis, M.D., M.P.H. Booklet created for the exhibit: Icons from the George Contis Collection Revelation Cast in Bronze SEPTEMBER 15 – NOVEMBER 13, 2015 Marian Library Gallery University of Dayton 300 College Park Dayton, Ohio 45469-1390 937-229-4214 All artifacts displayed in this booklet are included in the exhibit. The Nativity of Christ Triptych. 1650 AD. The Mother of God is depicted lying on her side on the middle left of this icon. Behind her is the swaddled Christ infant over whom are the heads of two cows. Above the Mother of God are two angels and a radiant star. The side panels have six pairs of busts of saints and angels. Christianity came to Russia in 988 when the ruler of Kiev, Prince Vladimir, converted. -

Medieval Music for St. John the Baptist from the Royal

Medieval Music for St. John the Baptist from the Royal Convents of Sigena (Hospitallers) and Las Huelgas (Cistercians) CANTRIX —— Medieval Music for —— Mittelalterliche Musik für —— Musique médiévale pour St. John the Baptist from Johannes den Täufer aus den St-Jean-Baptiste dans the Royal Convents of königlichen Frauen klöstern von les couvents royaux de Sigena Sigena (Hospitallers) and Sigena (Hospitaliterinnen) und (Hospitalières) et Las Huelgas Las Huelgas (Cistercians) Las Huelgas (Zisterzienserinnen) (Cisterciennes) Agnieszka Budzińska-Bennett (AB) — voice, harp, direction / Gesang, Harfe, Leitung / voix, harpe, direction Kelly Landerkin (KL) — voice / Gesang / voix Lorenza Donadini (LD) — voice / Gesang / voix Hanna Järveläinen (HJ) — voice / Gesang / voix Eve Kopli (EK) — voice / Gesang / voix Agnieszka M. Tutton (AT) — voice / Gesang / voix Baptiste Romain (BR) — vielle, bells / Vielle, Glocken / vielle, cloches Mathias Spoerry (MS) — voice / Gesang / voix Instrumente / Instruments Vielle (13th c.) — Roland Suits, Tartu (EE), 2006 Vielle (14th c.) — Judith Kra , Paris (F), 2007 Romanesque harp — Claus Henry Hüttel, Düren (D), 2001 Medieval bells — Michael Metzler, Berlin (D), 2012 Medieval Music for St. John the Baptist from the Royal Convents CANTRIX of Sigena (Hospitallers) and Las Huelgas (Cistercians) 1. Mulierium hodie/INTER NATOS 9. Benedicamus/Hic est enim precursor motet, Germany, 14th c. Benedicamus trope, Huelgas, 13th–14th c. AT, LD, EK (motetus), AB, HJ, KL (tenor), AB & HJ (trope), LD, EK, AT 01:44 BR (bells) 02:00 10. Peire Vidal – S’ieu fos en cort 2. Inter natos V. Hic venit/Preparator veritatis troubadour song, Aquitaine, 12th c. responsorium with prosula, Sigena, 14th–15th c. MS, BR (vielle) 07:04 HJ (verse), AB & LD (prosula), KL, EK, AT 04:04 11. -

Course Outline

Course Outline VTBS002 Exploring the New Testament Course Administrator: Mel Perkins Lay Leadership Development Coordinator eLM – Equipping Leadership for Mission Jesus Christ Pantocrator By Dianelos Georgoudis - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=33098123 Online Format Exploring the New Testament 2 Uniting Church in Australia, Synod of Victoria and Tasmania Greetings, and thank you for registering to be part of the Exploring the New Testament Course. In this Course Outline you will find details about the course, the outcomes and course content, a suggested 15 week study program, the assessment and other helpful information. This course has been developed to be a time of discipleship-forming and faith-expanding learning. This course is an indispensable resource for individuals and church study groups who want to learn more about their faith within a Uniting Church context. The course is also foundational for Lay Preachers, Worship Leaders, Mission Workers, and people engaged in other forms of Christian Leadership. The course integrates the study of theology with the study of scripture. We encourage you to approach your studies with a positive attitude and a willingness to be open to learning. Remember don’t be daunted by what lies ahead, as there will be help along the way. Thanks again for committing this time to your journey of understanding. We pray it will be a time of learning, with some challenge, and a time of deepening faith in God. MODES OF LEARNING Your Presbytery may offer different modes of learning: • Individual • Face-to-face groups • Online groups • A mixture of all or some of the above Talk with the person who looks after education in your Presbytery and find out how what learning modes are available. -

LUZ Mm AVELEYRA. ‘, 1987 D I I

A ST UDY OF CHRIST {N MNESTY FROM THE APOCALYPSE OF SAN SEVER w‘—-— § Thesis for the Degree of M. A. MlCHEGAN STATE {ENEVERSITY _‘ LUZ mm AVELEYRA. ‘, 1987 D I i I' .g IlllIIH3IIH1HIZIIHIHHHllllllllllllllllllllllllllllHllHll L - u.“ _ 291301062 3951 A LITTI’ARY 22‘2012n3tatc *.] UniV crsity ABJTRACT A dtudy_of Christ in Malestx of the Apocalypse of San Sever An analysis was done of an illustration taken from the Apocalypse of 8. never entitled Christ in Majesty. It was approached from a stylistic and iconographical vieWpoint and also includes historical data. The artist who illustrated the manuscript COpied his work from an earlier source. The attempt was made, there- fore, to find the manuscript which he may have used as the basis for his illustration. no definite conclusion was made as to the particular manuscript the artist may have COpied, but it was possible to state a period to which the earlier manuscript may have belonged. A STUDY OF CHRIST IN MAJESTY FROM THE APOCALYPSE OF SAN SEVER By / Luz Maria Aveleyra A THESIS Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Art 1967 ACthuLfiDGMENT To Professor Robert Rough for his interest, help and guidance, I express my sincere thanks. Luz Maria Aveleyra CoNTENTS Page Introduction -------------- 1 Historical Background --------- 4 Problems and Opinions --------- lO Iconography -------------- 17 Style ----------------- 29 Conclusion -------------- 39 Bibliography ------------- 43 Illustrations ------------- 47 INTRODUCTION At the close of the first century after Christ, a series of epistles were addressed to seven Asian churches by a writer known as John, probably the Apostle.1 Their message predicted events that would occur on earth, and in the kingdom of God at the end of the world. -

Signs of Royal Beauty Bright: Word and Image in the Legend of Charlemagne

Stephen G. Nichols, Jr. Signs of Royal Beauty Bright: Word and Image in the Legend of Charlemagne During the feast of Pentecost in the year 1000, there occurred an event which has been characterized as "the most spectacular of that year."1 It was the opening of Charlemagne's tomb at Aix-la-Chapelle by the emperor Otto III. Although the exact location of the tomb was not known, Otto chose a spot in the church and ordered the dig to begin. The excavations were immediately successful, and we have three progressively more elaborate ac- counts of what Otto found, one of them by a putative eyewitness. The first report is that given by Thietmar, bishop of Merseburg (975-1018), an exact contemporary of Otto. Thietmar reports that Otto: was in doubt as to the exact spot where the remains of the emperor Charles reposed. He ordered the stone floor to be secretly excavated at the spot where he thought them to be; at last they were discovered in a royal throne [a royal sarcophagus]. Taking the golden cross which hung from Charlemagne's neck, as well as the unrotted parts of his clothing, Otto replaced the rest with great reverence.2 While this account has found favor with historians for its comfort- ing lack of elaboration, it scarcely conveys the historic drama which came to be associated with the event. Happily that is provided by Otto of Lamello. Otto reports: We entered and went to Charles. He was not lying, as is the custom with the bodies of other deceased persons, but was sitting in a throne just like a living person. -

The Art of the Icon: a Theology of Beauty, Illustrated

THE ART OF THE ICON A Theology of Beauty by Paul Evdokimov translated by Fr. Steven Bigham Oakwood Publications Pasadena, California Table of Contents SECTION I: BEAUTY I. The Biblical Vision of Beauty II. The Theology of Beauty in the Fathers III. From Æsthetic to Religious Experience IV. The Word and the Image V. The Ambiguity of Beauty VI. Culture, Art, and Their Charisms VII. Modern Art in the Light of the Icon SECTION II: THE SACRED I. The Biblical and Patristic Cosmology II. The Sacred III. Sacred Time IV. Sacred Space V. The Church Building SECTION III: THE THEOLOGY OF THE ICON I. Historical Preliminaries II. The Passage from Signs to Symbols III. The Icon and the Liturgy IV. The Theology of Presence V. The Theology of the Glory-Light VI. The Biblical Foundation of the Icon VII. Iconoclasm VIII. The Dogmatic Foundation of the Icon IX. The Canons and Creative Liberty X. The Divine Art XI. Apophaticism SECTION IV: A THEOLOGY OF VISION I. Andrei Rublev’s Icon of the Holy Trinity II. The Icon of Our Lady of Vladimir III. The Icon of the Nativity of Christ IV. The Icon of the Lord’s Baptism V. The Icon of the Lord’s Transfiguration VI. The Crucifixion Icon VII. The Icons of Christ’s Resurrection VIII. The Ascension Icon IX. The Pentecost Icon X. The Icon of Divine Wisdom Section I Beauty CHAPTER ONE The Biblical Vision of Beauty “Beauty is the splendor of truth.” So said Plato in an affirmation that the genius of the Greek language completed by coining a single term, kalokagathia. -

The Great Feasts: the Life of Our Lord

Grade 4-5 The Great Feasts: The Life of Our Lord A program from The Department of Christian Education, Antiochian Orthodox Archdiocese of North America, funded in part by The Order of St. Ignatius of Antioch Above: Icon of Christ Pantocrator from Hagia Sofia, Constantinople Beloved Teacher, Orthodox Christians, ideally, have one foot walking in the temporal year and the other in the Church’s liturgical year—one foot on earth and the other in heaven. The foot that walks the liturgi- cal year keeps us in touch with the eternal, important events of the life of Jesus and his mother, the Theotokos. Although the term, “liturgical year” includes all the services and readings for the year, it is often used to speak of Pascha and The Twelve Great Feasts. We consider Pascha as “the feast of feasts,” hence it is called out when we speak of the Great Feasts of the liturgical year. The Church Year begins on September 1. The feasts are listed in temporal chronological order below. The Great Feasts Pascha! 1. Nativity of the Theotokos September 8 7. Annunciation, March 25 2. Elevation of the Holy Cross, September 14 8. Palm Sunday, the Sunday before Pascha 3. Presentation of the Theotokos, 9. Ascension, Forty Days after Pascha November 21 10. Pentecost, Fifty Days after Pascha 4. Nativity of Christ, December 25 11. Transfiguration,August 6 5. Theophany, January 6 12. Dormition of the Theotokos, August 15 6. Presentation of the Lord, February 2 Through the Great Feasts we are kept in touch with the reality of Jesus Christ, When we remember any of the events of His life story, we also remember the His promise at the end: one day He will come again and we will live eternally in His Kingdom. -

Iconography of Jesus Christ in Nubian Painting 242 MAŁGORZATA MARTENS-CZARNECKA

INSTITUT DES CULTURES MÉDITERRANÉENNES ET ORIENTALES DE L’ACADÉMIE POLONAISE DES SCIENCES ÉTUDES et TRAVAUX XXV 2012 MAŁGORZATA MARTENS-CZARNECKA Iconography of Jesus Christ in Nubian Painting 242 MAŁGORZATA MARTENS-CZARNECKA In religious art the image of Christ was one of the key elements which inspired the faithful to prayer and contemplation. Pictured as the Incarnation of Logos, the Son of God, the Child born unto Mary, the fi gure of Christ embodied the most important dogma of Christianity.1 Depicted in art, Christ represents the hypostasis of the Word made man – the Logos in human form.2 Christ the Logos was made man (κατά τόν ανθρώπινον χαρακτήρα). God incarnate, man born of Mary, as dictated by canon 82 of the Synod In Trullo in Constan- tinople (AD 692), was to be depicted only in human form, replacing symbols (the lamb).3 From the moment of incarnation, the image of Christ became easily perceptible to the human eye, and hence readily defi ned in shape and colour.4 Artists painting representations of Christ drew inspiration from the many descriptions recorded in the apocrypha: ... and with him another, whose countenance resembled that of man. His countenance was full of grace, like that of one of the holy angels (1 Enoch 46:1). For humankind Christ was the most essential link between the seen and the unseen, between heaven and Earth;5 the link between God and the men sent by God (John 1:6; 3:17; 5:22-24), through whom God endows the world with all that is good. He is the mediator to whom the faithful, often through the intercession of the Virgin, make supplication and prayer – if you ask the Father anything in my name, he will give it to you (John 16:23; 14:11-14; 15:16). -

Sung Eucharist

THE CATHEDRAL AND METROPOLITICAL CHURCH OF CHRIST, CANTERBURY Sung Eucharist Christ the King 22nd November 2020 10.30am Nave Welcome to Canterbury Cathedral for this Service The setting of the Service is Messe cum jubilo – Maurice Duruflé (1902-1986) Please ask the priest if you require a gluten-free communion wafer For your safety Please keep social distance at all times Please stay in your seat as much as possible Please use hand sanitiser on the way in and out Please avoid touching your face and touching surfaces Cover Image: ‘Christ in Majesty’, Jesus Chapel enlarged copy of 15th century icon by Andrei Rublev (d. c1428) As part of our commitment to the care of the environment in our world, this Order of Service is printed on unbleached 100% recycled paper Please ensure that mobile phones are switched off. No form of visual or sound recording, or any form of photography, is permitted during Services. Thank you for your co-operation. An induction loop system for the hard of hearing is installed in the Cathedral. Hearing aid users should adjust their aid to T. Large print orders of service are available from the stewards and virgers. Please ask. Some of this material is copyright: © Archbishops’ Council, 2000 © Archbishops’ Council, 2006 Hymns and songs reproduced under CCLI number: 1031280 Produced by the Music & Liturgy Department: [email protected] 01227 865281 www.canterbury-cathedral.org The Gathering Before the Service begins the Dean offers a welcome The President says In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. -

Christology and the 'Scotist Rupture'

Theological Research ■ volume 1 (2013) ■ p. 31–63 Aaron Riches Instituto de Filosofía Edith Stein Instituto de Teología Lumen Gentium, Granada, Spain Christology and the ‘Scotist Rupture’ Abstract This essay engages the debate concerning the so-called ‘Scotist rupture’ from the point of view of Christology. The essay investigates John Duns Scotus’s de- velopment of Christological doctrine against the strong Cyrilline tendencies of Thomas Aquinas. In particular the essay explores how Scotus’s innovative doctrine of the ‘haecceity’ of Christ’s human nature entailed a self-sufficing conception of the ‘person’, having to do less with the mystery of rationality and ‘communion’, and more to do with a quasi-voluntaristic ‘power’ over oneself. In this light, Scotus’s Christological development is read as suggestively con- tributing to make possible a proto-liberal condition in which ‘agency’ (agere) and ‘right’ (ius) are construed as determinative of what it means to be and act as a person. Keywords John Duns Scotus, ‘Scotist rupture’, Thomas Aquinas, homo assumptus Christology 32 Aaron Riches Introduction In A Secular Age, Charles Taylor links the movement towards the self- sufficing ‘exclusive humanism’ characteristic of modern secularism with a reallocation of popular piety in the thirteenth century.1 Dur- ing that period a shift occurred in which devotional practices became less focused on the cosmological glory of Christ Pantocrator and more focused on the particular humanity of the lowly Jesus. Taylor suggests that this new devotional attention to the particular human Christ was facilitated by the recently founded mendicant orders, especially the Franciscans and Dominicans, both of whom saw the meekness of God Incarnate reflected in the individual poor among whom the friars lived and ministered. -

Monastery of Agios Ioannis (Saint John) Lampadistis

Monastery of Agios Ioannis (Saint John) Lampadistis We do not have any information for the construction date of the Monastery; however it might be placed most probably in the mid‐16th century. The church is the oldest building of the Monastery. The Monastery is constituted by two separate two‐storied buildings. The south wing comprises the oven and the gyle of the Monastery. Here there was a porch that protected from rain and storminess. The main entrance of the Monastery was west of the bakery. In the east wing of the Monastery there are 4 ground floor rooms; one of them was the wine press, and the other one was the olive press. We do not know much about the use of the other 2 rooms. The west and east wing of the Monastery are two‐storied buildings, erected in various periods. The rooms of the ground floor are half under the ground. One of the first floor rooms was used as a school. The other rooms were used as the dining room of the Monastery, the cells, the consistory and the priory. The consistory and the priory are the only parts dated through an inscription to the 18th century, and more precisely to 1782. The Katholikon (the main church) The north wing of the Monastery consists of the Katholikon (the main church), which is the oldest building and the two adjacent chapels in the north wall of the main church. The main church, that is to say the central Church, dedicated to Saint Heracleidius, is dated to the 11th century.