Shifted Baselines, Forensic Taxonomy, and Rabbs' Fringe-Limbed Treefrog

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The New Age of Extinction

Wednesday, Apr. 01, 2009 The New Age of Extinction By Bryan Walsh / Madagascar There are at least 8 million unique species of life on the planet, if not far more, and you could be forgiven for believing that all of them can be found in Andasibe. Walking through this rain forest in Madagascar is like stepping into the library of life. Sunlight seeps through the silky fringes of the Ravenea louvelii, an endangered palm found, like so much else on this African island, nowhere else. Leaf-tailed geckos cling to the trees, cloaked in green. A fat Parson's chameleon lies lazily on a branch, beady eyes scanning for dinner. But the animal I most hoped to find, I don't see at first; I hear it, though — a sustained groan that electrifies the forest quiet. My Malagasy guide, Marie Razafindrasolo, finds the source of the sound perched on a branch. It is the black-and-white indri, largest of the lemurs — a type of small primate found only in Madagascar. The cry is known as a spacing call, a warning to other indris to keep their distance, to prevent competition for food. But there's not much risk of interlopers. The species — like many other lemurs, like many other animals in Madagascar, like so much of life on Earth — is endangered and dwindling fast. Madagascar — which separated from India 80 million to 100 million years ago before eventually settling off the southeastern coast of Africa — is in many ways an Earth apart. All that time in geographic isolation made Madagascar a Darwinian playground, its animals and plants evolving into forms utterly original. -

Newsletter V5-N2

V irg in ia Herpetological Society August 1995 Volume 5, Number 2 NEWSLETTER Catesheiana Co-editors President Paul W. Saltier Ron Southwick R. Terry Spohn Paul Sattler - Pres. Elect Newsletter Editor Sccrctarv/Trcasurcr Mike Finder Bob Hogan microdistribution patterns of Worldwide Amphibian Decline salamanders in terrestrial environments Is There a Virginia Connection? (Wyman and Hawksley-Lescault, 1987). Increased ultraviolet radiation, apparently due to the thinning of the Submitted by Joseph C. Mitchell, Department of Biology, ozone layer, has been shown to k ill University o f Richmond, Richmond, VA 23173 developing eggs of the Cascades frog (Rana cascadae) and western toad (Bufo boreas) (Blaustein et al., 1994a). Amphibians have received Congress of Herpetology held in The widespread fungus (Saprolegnia considerable media and scientific Canterbury, England in 1989. ferax) introduced into ponds and lakes attention over the past half dozen years Pin-pointing the causes of in the Pacific northwest by introduced because of species extinctions and these problems has been elusive. Early fish has caused egg mortality in the population declines worldwide. on, scientists were looking for one western toad (Blaustein et al., 1994b). Observations such as (1) the last global smoking gun, but the results of An unidentified virus carried by individual of the Australian gastric studies that have been published since introduced fish, such as tilapia, brooding frog (Rheobatrachus silus) the alarm surfaced indicate that the guppies, and carp, is suspected as was seen in 1979 (Tyler and Davies, causes are varied and often local. The causing frog decline in Australia 1985); (2) the golden toad (Bufo most common cause of local population (Anderson, 1995). -

Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca

Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca John F. Lamoreux, Meghan W. McKnight, and Rodolfo Cabrera Hernandez Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 53 Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca John F. Lamoreux, Meghan W. McKnight, and Rodolfo Cabrera Hernandez Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission No. 53 The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of IUCN or other participating organizations. Published by: IUCN, Gland, Switzerland Copyright: © 2015 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Lamoreux, J. F., McKnight, M. W., and R. Cabrera Hernandez (2015). Amphibian Alliance for Zero Extinction Sites in Chiapas and Oaxaca. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN. xxiv + 320pp. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1717-3 DOI: 10.2305/IUCN.CH.2015.SSC-OP.53.en Cover photographs: Totontepec landscape; new Plectrohyla species, Ixalotriton niger, Concepción Pápalo, Thorius minutissimus, Craugastor pozo (panels, left to right) Back cover photograph: Collecting in Chamula, Chiapas Photo credits: The cover photographs were taken by the authors under grant agreements with the two main project funders: NGS and CEPF. -

Multi-National Conservation of Alligator Lizards

MULTI-NATIONAL CONSERVATION OF ALLIGATOR LIZARDS: APPLIED SOCIOECOLOGICAL LESSONS FROM A FLAGSHIP GROUP by ADAM G. CLAUSE (Under the Direction of John Maerz) ABSTRACT The Anthropocene is defined by unprecedented human influence on the biosphere. Integrative conservation recognizes this inextricable coupling of human and natural systems, and mobilizes multiple epistemologies to seek equitable, enduring solutions to complex socioecological issues. Although a central motivation of global conservation practice is to protect at-risk species, such organisms may be the subject of competing social perspectives that can impede robust interventions. Furthermore, imperiled species are often chronically understudied, which prevents the immediate application of data-driven quantitative modeling approaches in conservation decision making. Instead, real-world management goals are regularly prioritized on the basis of expert opinion. Here, I explore how an organismal natural history perspective, when grounded in a critique of established human judgements, can help resolve socioecological conflicts and contextualize perceived threats related to threatened species conservation and policy development. To achieve this, I leverage a multi-national system anchored by a diverse, enigmatic, and often endangered New World clade: alligator lizards. Using a threat analysis and status assessment, I show that one recent petition to list a California alligator lizard, Elgaria panamintina, under the US Endangered Species Act often contradicts the best available science. -

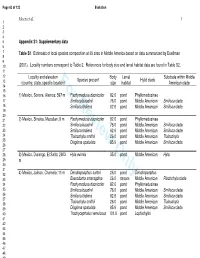

For Review Only

Page 63 of 123 Evolution Moen et al. 1 1 2 3 4 5 Appendix S1: Supplementary data 6 7 Table S1 . Estimates of local species composition at 39 sites in Middle America based on data summarized by Duellman 8 9 10 (2001). Locality numbers correspond to Table 2. References for body size and larval habitat data are found in Table S2. 11 12 Locality and elevation Body Larval Subclade within Middle Species present Hylid clade 13 (country, state, specific location)For Reviewsize Only habitat American clade 14 15 16 1) Mexico, Sonora, Alamos; 597 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 17 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 18 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 19 20 21 2) Mexico, Sinaloa, Mazatlan; 9 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 22 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 23 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 24 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 25 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 26 27 28 3) Mexico, Durango, El Salto; 2603 Hyla eximia 35.0 pond Middle American Hyla 29 m 30 31 32 4) Mexico, Jalisco, Chamela; 11 m Dendropsophus sartori 26.0 pond Dendropsophus 33 Exerodonta smaragdina 26.0 stream Middle American Plectrohyla clade 34 Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 35 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 36 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 37 38 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 39 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 40 Trachycephalus venulosus 101.0 pond Lophiohylini 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Evolution Page 64 of 123 Moen et al. -

The Puzzling Golden Toad Crack the Puzzle and Reveal the Secret Word Activity Guide

The Puzzling Golden Toad Crack the puzzle and reveal the secret word Activity Guide Did you know that the specific effects of climate change on animals are still unknown? Meet the golden toad and learn why scientists are still puzzled by his mysterious disappearance. Try This! Step 1: Set up the time line sheet. Step 2: Find the seven puzzle pieces and read the information on each. Step 3: Organize the time line to reveal the secret word. How do you think scientists study the effect of climate change on species such as the Golden Toad? Climate Connection The effect of climate change on species is still unknown and widely debated. Scientists believe that factors such as increased droughts and the spread of a fungus may have led to the demise of the Golden Toad. The number of Golden Toads people saw declined from 1,500 to zero in such a short period of time. Scientists suspect that conditions related to climate change was the reason for their extinction. Turn the page over to learn more! Sciencenter, Ithaca, NY Page 1 www.sciencenter.org The Puzzling Golden Toad Activity Guide What’s Happening? The Golden Toad (Bufo periglenes) was an amphibian only found in areas near the Monteverde Cloud Forest Preserve in Costa Rica. This species strangely disappeared in the late 1980’s, which led to extensive studies on what caused the extinction of this species. After studying the drastic manner in which this species declined, scientists started to suspect that climate change was the reason for their extinction. Scientists began to study how stress relating to moisture, temperature, diseases and contaminants in combination with climate change could have affected the Golden Toad. -

The IUCN Amphibians Initiative: a Record of the 2001-2008 Amphibian Assessment Efforts for the IUCN Red List

The IUCN Amphibians Initiative: A record of the 2001-2008 amphibian assessment efforts for the IUCN Red List Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Amphibians on the IUCN Red List - Home Page ................................................................................ 5 Assessment process ......................................................................................................................... 6 Partners ................................................................................................................................................................. 6 The Central Coordinating Team ............................................................................................................................ 6 The IUCN/SSC – CI/CABS Biodiversity Assessment Unit........................................................................................ 6 An Introduction to Amphibians ................................................................................................................................. 7 Assessment methods ................................................................................................................................................ 7 1. Data Collection .................................................................................................................................................. 8 2. Data Review ................................................................................................................................................... -

Golden Toad Fact Sheet

Golden Toad Fact Sheet Common Name: Golden Toad Scientific Name: Incilius periglenes, formerly Bufo periglenes Wild Status: Extinct Habitat: Cloud Forest Country: Costa Rica Shelter: Underground Life Span: Estimated 10 Years Size: 3 inches approx Details The golden toad is one of the many victims of global decline in amphibians. The causes are not well understood for amphibians or for the golden toad. Because golden toads laid many eggs in shallow pools, some speculate a drought harmed the toad population. Others believe it may be a combination of climate change, air pollution, and disease. As amphibian populations continue to decline, biologists look to the case of the golden toad as a sign of what could happen not just to toads, but any cold blooded creature sensitive to its surroundings. Cool Facts • Like many other toads, this species spent much of its life underground, waiting for the rain. • Was found only in Costa Rica in what is called a "cloud forest" due to the constant, cloudy fog. • Females were bigger than males and came in a variety of colors. Males were usually golden in color. • Unlike cane toads, the golden toads did not have poison • The last golden toad was seen in 1989. In 2004, it was considered extinct. Taxonomic Breakdown Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Amphibia Order: Anura Family: Bufonidae Genus: Incilius Species: I. periglenes Conservation & Helping Although the toads were closely examined and counted each year, scientists were not able to stop the decline of the toad, and they are considered extinct. Their average lifespan are just over 10 years, and no golden toads have been seen in decades. -

Spindly Leg Syndrome, a Review by Ed Kowalski Photos © Ed Kowalski

Director’s Welcome The Magazine of Tree Walkers International Road to Stewardship There is a peculiar human drive to RON SKYLSTAD organize and categorize, and in the Editor conservation world it is no different. © Jason Brown When we first aligned ourselves organizationally with our goals at ED KOWALSKI TWI, we examined the individuals and organizations involved in NATHANIEL PAULL our corner of the amphibian conservation effort and looked for a Assistant Editors structure that would reflect the organization’s ethos. Eventually, we settled on “stewards” working as part of an amphibian “network.” And so, our loose grouping of captive amphibian keepers became the MARCOS OSORNO Amphibian Steward Network (ASN). Executive Director As we move forward, I ask for your help in the stewardship of two wonderful, interrelated things. First and foremost, in the continued BRENT L. BROCK care and conservation of amphibians and their habitat. In TWI, we Program Director all share a connection to our natural world through amphibians. Those who keep amphibians in captivity maintain a window into a natural habitat under immense pressures. This connection to nature MISSION STATEMENT is vital to maintaining a conservation ethos, and I am proud to be Tree Walkers International supports the part of a community through a wonderful hobby that is steeped protection, conservation, and restoration of in ethical traditions and perennially introspective in regards to its wild amphibian populations through hands-on future. action both locally and internationally. Next, I ask for your help in stewardship of the network itself. We foster personal relationships between people and nature by providing opportunities TWI and ASN are volunteer driven projects. -

Biodiversity, Scientists, and Religious Communities: Conservation Through Collaboration 10 March 2016 Christine A

MENU (/) Read More News Stories (/news) Biodiversity, Scientists, and Religious Communities: Conservation Through Collaboration 10 March 2016 Christine A. Scheller (/person/christine-scheller) Tweet (https://www.reddit.com/submit) CENTER OF SCIENCE, POLICY AND SOCIETY PROGRAMS (/TOPICS/CENTER-SCIENCE-POLICY-AND-SOCIETY- PROGRAMS) DIALOGUE ON SCIENCE, ETHICS, AND RELIGION (/TOPICS/DIALOGUE-SCIENCE-ETHICS-AND-RELIGION) BIODIVERSITY, SCIENTISTS, AND RELIGIOUS COMMUNITIES: CONSERVATION THROUGH COLLABORATION|AAAS Speaker(s) Time Se Kim 00:00-10:01 Karen Lips 10:02-31:07 Peyton West 31:08-50:04 William Brown 50:05-109:17 Panel Discussion 109:18-1:29:59 Audience Q&A 1:30:00-1:31:55 Religious communities are too often an underutilized resource in protecting Earth’s most vulnerable ecosystems, speakers said at a DoSER-sponsored AAAS Annual Meeting symposium (https://aaas.confex.com/aaas/2016/webprogram/Session12428.html) on February 13. Conservation biologist Karen Lips (http://biology.umd.edu/karen-lips.html) and wildlife ecologist Peyton West (https://www.linkedin.com/in/peyton-west-bb52754a) outlined the extent of the worldwide ecological crisis and the potential for collaboration between conservationists and religious communities, while theologian William Brown made a scriptural case for such efforts and environmental journalist Daniel Grossman moderated the discussion. Lips, Director of Graduate Program in Sustainable Development and Conservation Biology at the University of Maryland, College Park, drew upon the troubling story of worldwide amphibian decline to make her points while West, Executive Director of the Frankfurt Zoological Society-U.S. (and former DoSER project director), discussed how her conservation efforts in Africa and South East Asia are impacted for both good and ill by religious communities. -

The Golden Frogs of Panama (Atelopus Zeteki, A. Varius): a Conservation Planning Workshop

The Golden Frogs of Panama The Golden Frogs of Panama (Atelopus zeteki, A. (Atelopus zeteki, A. varius): varius) A Conservation Planning Workshop A Conservation Planning Workshop 19-22 November 2013 El Valle, Panama The Golden Frogs of Panama (Atelopus zeteki, A. varius): A Conservation Planning Workshop 19 – 22 November, 2013 El Valle, Panama FINAL REPORT Workshop Conveners: Project Golden Frog Association of Zoos and Aquariums Golden Frog Species Survival Plan Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project Workshop Hosts: El Valle Amphibian Conservation Center Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute Workshop Design and Facilitation: IUCN / SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group Workshop Support: The Shared Earth Foundation An Anonymous Frog-Friendly Foundation Photos courtesy of Brian Gratwicke (SCBI) and Phil Miller (CBSG). A contribution of the IUCN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group, in collaboration with Project Golden Frog, the Association of Zoos and Aquariums Golden Frog Species Survival Plan, the Panama Amphibian Rescue and Conservation Project, the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, and workshop participants. This workshop was conceived and designed by the workshop organization committee: Kevin Barrett (Maryland Zoo), Brian Gratwicke (SCBI), Roberto Ibañez (STRI), Phil Miller (CBSG), Vicky Poole (Ft. Worth Zoo), Heidi Ross (EVACC), Cori Richards-Zawacki (Tulane University), and Kevin Zippel (Amphibian Ark). Workshop support provided by The Shared Earth Foundation and an anonymous frog-friendly foundation. Estrada, A., B. Gratwicke, A. Benedetti, G. DellaTogna, D. Garrelle, E. Griffith, R. Ibañez, S. Ryan, and P.S. Miller (Eds.). 2014. The Golden Frogs of Panama (Atelopus zeteki, A. varius): A Conservation Planning Workshop. Final Report. Apple Valley, MN: IUSN/SSC Conservation Breeding Specialist Group. -

Yosemite Toad Conservation Assessment

United States Department of Agriculture YOSEMITE TOAD CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT A Collaborative Inter-Agency Project Forest Pacific Southwest R5-TP-040 January Service Region 2015 YOSEMITE TOAD CONSERVATION ASSESSMENT A Collaborative Inter-Agency Project by: USDA Forest Service California Department of Fish and Wildlife National Park Service U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Technical Coordinators: Cathy Brown USDA Forest Service Amphibian Monitoring Team Leader Stanislaus National Forest Sonora, CA [email protected] Marc P. Hayes Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Research Scientist Science Division, Habitat Program Olympia, WA Gregory A. Green Principal Ecologist Owl Ridge National Resource Consultants, Inc. Bothel, WA Diane C. Macfarlane USDA Forest Service Pacific Southwest Region Threatened Endangered and Sensitive Species Program Leader Vallejo, CA Amy J. Lind USDA Forest Service Tahoe and Plumas National Forests Hydroelectric Coordinator Nevada City, CA Yosemite Toad Conservation Assessment Brown et al. R5-TP-040 January 2015 YOSEMITE TOAD WORKING GROUP MEMBERS The following may be the contact information at the time of team member involvement in the assessment. Becker, Dawne Davidson, Carlos Harvey, Jim Associate Biologist Director, Associate Professor Forest Fisheries Biologist California Department of Fish and Wildlife Environmental Studies Program Humboldt-Toiyabe National Forest 407 West Line St., Room 8 College of Behavioral and Social Sciences USDA Forest Service Bishop, CA 93514 San Francisco State University 1200 Franklin Way (760) 872-1110 1600 Holloway Avenue Sparks, NV 89431 [email protected] San Francisco, CA 94132 (775) 355-5343 (415) 405-2127 [email protected] Boiano, Daniel [email protected] Aquatic Ecologist Holdeman, Steven J. Sequoia/Kings Canyon National Parks Easton, Maureen A.