A Fisheries Survey Big Wichita River System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indiana Species April 2007

Fishes of Indiana April 2007 The Wildlife Diversity Section (WDS) is responsible for the conservation and management of over 750 species of nongame and endangered wildlife. The list of Indiana's species was compiled by WDS biologists based on accepted taxonomic standards. The list will be periodically reviewed and updated. References used for scientific names are included at the bottom of this list. ORDER FAMILY GENUS SPECIES COMMON NAME STATUS* CLASS CEPHALASPIDOMORPHI Petromyzontiformes Petromyzontidae Ichthyomyzon bdellium Ohio lamprey lampreys Ichthyomyzon castaneus chestnut lamprey Ichthyomyzon fossor northern brook lamprey SE Ichthyomyzon unicuspis silver lamprey Lampetra aepyptera least brook lamprey Lampetra appendix American brook lamprey Petromyzon marinus sea lamprey X CLASS ACTINOPTERYGII Acipenseriformes Acipenseridae Acipenser fulvescens lake sturgeon SE sturgeons Scaphirhynchus platorynchus shovelnose sturgeon Polyodontidae Polyodon spathula paddlefish paddlefishes Lepisosteiformes Lepisosteidae Lepisosteus oculatus spotted gar gars Lepisosteus osseus longnose gar Lepisosteus platostomus shortnose gar Amiiformes Amiidae Amia calva bowfin bowfins Hiodonotiformes Hiodontidae Hiodon alosoides goldeye mooneyes Hiodon tergisus mooneye Anguilliformes Anguillidae Anguilla rostrata American eel freshwater eels Clupeiformes Clupeidae Alosa chrysochloris skipjack herring herrings Alosa pseudoharengus alewife X Dorosoma cepedianum gizzard shad Dorosoma petenense threadfin shad Cypriniformes Cyprinidae Campostoma anomalum central stoneroller -

2020 Draft Basin Highlights Report an Overview of Water Quality Issues Throughout the Canadian and Red River Basins

2020 DRAFT BASIN HIGHLIGHTS REPORT AN OVERVIEW OF WATER QUALITY ISSUES THROUGHOUT THE CANADIAN AND RED RIVER BASINS The preparation of this report was financed through and in cooperation with the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality North Fork Red River at FM 2473 2020 Canadian and Red River Basins Highlights Report ~ Page 2020 Canadian and Red River Basins Highlights Report ~ Page 2 Lake Texoma at US 377 Bridge TABLE OF CONTENTS CANADIAN AND RED RIVER BASIN VICINITY MAP 4 INTRODUCTION 5 Public Involvement Basin Advisory Committee Meeting 6 Coordinated Monitoring Meeting 7 Zebra Mussels Origin, Transportation, Impact, Texas Bound, Current Populations, and Studies 8 Texas Legislation Action 9 CANADIAN AND RED RIVER BASINS WATER QUALITY OVERVIEW AND HIGHLIGHTS Canadian and Red River Basins Water Quality Overview, 2018 Texas IR Overview 10 TABLES Canadian River Basin 2018 Texas IR Impairment Listing 11 Red River Basin 2018 Texas IR Impairment Listing 12 Water Quality Monitoring Field Parameters, Conventional Laboratory Parameters Red River Authority Environmental Services Laboratory Environmental Services Division 15 2020 Canadian and Red River Basins Highlights Report ~ Page 3 2020 Canadian and Red River Basins Highlights Report ~ Page 4 INTRODUCTION In 1991, the Texas Legislature enacted the Texas Clean Rivers Act (Senate Bill 818) in order to assess water quality for each river basin in the state. From this, the Clean Rivers Program (CRP) was created and has become one of the most successful cooperative efforts between federal, state, and local agen- cies and the citizens of the State of Texas. It is implemented by the Texas Commission on Environ- mental Quality (TCEQ) through local partner agencies to achieve the CRP’s primary goal of maintain- ing and improving the water quality in each river basin. -

Classified Stream Segments and Assessments Units Covered by Hb 4146

CLASSIFIED STREAM SEGMENTS AND ASSESSMENTS UNITS COVERED BY HB 4146 SEG ID River Basin Description Met criteria 0216 Red Wichita River Below Lake Kemp Dam 96.43% 0222 Red Salt Fork Red River 95.24% 0224 Red North Fork Red River 90.91% 1250 Brazos South Fork San Gabriel River 93.75% 1251 Brazos North Fork San Gabriel River 93.55% 1257 Brazos Brazos River Below Lake Whitney 90.63% 1415 Colorado Llano River 94.39% 1424 Colorado Middle Concho/South Concho River 95.24% 1427 Colorado Onion Creek 93.43% 1430 Colorado Barton Creek 98.25% 1806 Guadalupe Guadalupe River Above Canyon Lake 96.37% 1809 Guadalupe Lower Blanco River 95.83% 1811 Guadalupe Comal River 98.90% 1812 Guadalupe Guadalupe River Below Canyon Dam 96.98% 1813 Guadalupe Upper Blanco River 95.45% 1815 Guadalupe Cypress Creek 99.19% 1816 Guadalupe Johnson Creek 97.30% AU ID River Basin Description Met criteria 1817 Guadalupe North Fork Guadalupe River 100.00% 1414_01 Colorado Pedernales River 93.10% 1818 Guadalupe South Fork Guadalupe River 97.30% 1414_03 Colorado Pedernales River 91.38% 1905 San Antonio Medina River Above Medina Lake 100.00% 1416_05 Colorado San Saba River 100.00% 2111 Nueces Upper Sabinal River 100.00% Colorado River Below Lady Bird Lake 2112 Nueces Upper Nueces River 95.96% 1428_03 Colorado (formally Town Lake) 91.67% 2113 Nueces Upper Frio River 100.00% Medina River Below Medina 1903_04 San Antonio Diversion Lake 90.00% 2114 Nueces Hondo Creek 93.48% Medina River Below Medina 2115 Nueces Seco Creek 95.65% 1903_05 San Antonio Diversion Lake 96.84% 2309 Rio Grande Devils River 96.67% 1908_02 San Antonio Upper Cibolo Creek 97.67% 2310 Rio Grande Lower Pecos River 93.88% 2304_10 Rio Grande Rio Grande Below Amistad Reservoir 95.95% 2313 Rio Grande San Felipe Creek 95.45% 2311_01 Rio Grande Upper Pecos River 92.86% A detailed map of covered segments and assessment units can be found on the TCEQ website https://www.tceq.texas.gov/gis/nonpoint-source-project-viewer . -

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Land

United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Land & Water Conservation Fund --- Detailed Listing of Grants Grouped by County --- Today's Date: 11/20/2008 Page: 1 Texas - 48 Grant ID & Type Grant Element Title Grant Sponsor Amount Status Date Exp. Date Cong. Element Approved District ANDERSON 396 - XXX D PALESTINE PICNIC AND CAMPING PARK CITY OF PALESTINE $136,086.77 C 8/23/1976 3/1/1979 2 719 - XXX D COMMUNITY FOREST PARK CITY OF PALESTINE $275,500.00 C 8/23/1979 8/31/1985 2 ANDERSON County Total: $411,586.77 County Count: 2 ANDREWS 931 - XXX D ANDREWS MUNICIPAL POOL CITY OF ANDREWS $237,711.00 C 12/6/1984 12/1/1989 19 ANDREWS County Total: $237,711.00 County Count: 1 ANGELINA 19 - XXX C DIBOLL CITY PARK CITY OF DIBOLL $174,500.00 C 10/7/1967 10/1/1971 2 215 - XXX A COUSINS LAND PARK CITY OF LUFKIN $113,406.73 C 8/4/1972 6/1/1973 2 297 - XXX D LUFKIN PARKS IMPROVEMENTS CITY OF LUFKIN $49,945.00 C 11/29/1973 1/1/1977 2 512 - XXX D MORRIS FRANK PARK CITY OF LUFKIN $236,249.00 C 5/20/1977 1/1/1980 2 669 - XXX D OLD ORCHARD PARK CITY OF DIBOLL $235,066.00 C 12/5/1978 12/15/1983 2 770 - XXX D LUFKIN TENNIS IMPROVEMENTS CITY OF LUFKIN $51,211.42 C 6/30/1980 6/1/1985 2 879 - XXX D HUNTINGTON CITY PARK CITY OF HUNTINGTON $35,313.56 C 9/26/1983 9/1/1988 2 ANGELINA County Total: $895,691.71 County Count: 7 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service Land & Water Conservation Fund --- Detailed Listing of Grants Grouped by County --- Today's Date: 11/20/2008 Page: 2 Texas - 48 Grant ID & Type Grant Element Title Grant Sponsor Amount Status Date Exp. -

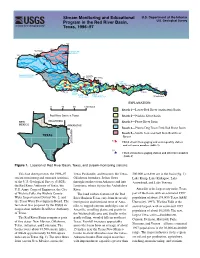

Stream Monitoring and Educational Program in the Red River Basin

Stream Monitoring and Educational U.S. Department of the Interior Program in the Red River Basin, U.S. Geological Survey Texas, 1996–97 100 o 101 o 5 AMARILLO NORTH FORK 102 o RED RIVER 103 o A S LT 35o F ORK RED R IV ER 1 4 2 PRAIRIE DOG TOWN PEASE 3 99 o WICHITA FORK RED RIVER 7 FALLS CHARLIE 6 RIVE R o o 34 W 8 98 9 I R o LAKE CHIT 21 ED 97 A . TEXOMA o VE o 10 11 R 25 96 RI R 95 16 19 18 20 DENISON 17 28 14 15 23 24 27 29 22 26 30 12,13 LAKE PARIS KEMP LAKE LAKE KICKAPOO ARROWHEAD TEXARKANA EXPLANATION 0 40 80 120 MILES Reach 1—Lower Red River (mainstem) Basin Red River Basin in Texas Reach 2—Wichita River Basin NEW OKLAHOMA Reach 3—Pease River Basin MEXICO ARKANSAS Reach 4—Prairie Dog Town Fork Red River Basin Reach 5—North Fork and Salt Fork Red River TEXAS Basins 12 LOUISIANA USGS streamflow-gaging and water-quality station and reference number (table 1) 22 USGS streamflow-gaging station and reference number (table 1) Figure 1. Location of Red River Basin, Texas, and stream-monitoring stations. This fact sheet presents the 1996–97 Texas Panhandle, and becomes the Texas- 200,000 acre-feet are in the basin (fig. 1): stream monitoring and outreach activities Oklahoma boundary. It then flows Lake Kemp, Lake Kickapoo, Lake of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), through southwestern Arkansas and into Arrowhead, and Lake Texoma. -

The Scientific Names Notropis Stramineus (Cope) and N

Am. Midl. Nat. 151:164 Notes The Scientific Names Notropis stramineus (Cope) and N. ludibundus (Girard) ABSTRACT.—Two scientific names referring to the sand shiner have appeared in the literature during the past decade. A ruling by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature in 2002 (Opinion, 1991) conserved the more commonly used name, Notropis stramineus (Cope, 1865), and this name should be used rather than the name N. ludibundus (Girard, 1856). The sand shiner is a small species of minnow (family Cyprinidae) occurring most often in lotic waters of the eastern and central United States and southern Canada (Lee et al., 1980). Several scientific names have been proposed for the sand shiner; however, the name Notropis stramineus, originally Hybognathus stramineus Cope, 1865, has been the most widely used name for this species. In 1989, the name N. ludibundus, originally Cyprinella ludibunda Girard, 1856, was resurrected for the sand shiner by Mayden and Gilbert (1989). Since then, both names have appeared in the literature, leading to nomenclatural instability. In the interest of preserving nomenclatural stability, Bailey (1999) submitted a petition to the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) to conserve the name H. stramineus Cope for the sand shiner instead of the slightly older but little-used name C. ludibunda Girard. Comments from ichthyologists on the case were published in the Bulletin of Zoological Nomenclature [2000. 57(2):111–112, 57(3):168–172] and in March 2002 the ICZN published their ruling on the matter (ICZN, 2002). The decision of the ICZN was to conserve the name N. stramineus; therefore, this name should be used for the sand shiner rather than the name N. -

Index of Surface Water Stations in Texas

1 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY I AUSTIN, TEXAS INDEX OF SURFACE WATER STATIONS IN TEXAS Operated by the Water Resources Division of the Geological Survey in cooperation with State and Federal Agencies Gaging Station 08065000. Trinity River near Oakwood , October 1970 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Geological Survey - Water Resources Division INDEX OF SURFACE WATER STATIONS IN TEXAS OCTOBER 1970 Copies of this report may be obtained from District Chief. Water Resources Division U.S. Geological Survey Federal Building Austin. Texas 78701 1970 CONTENTS Page Introduction ............................... ................•.......•...•..... Location of offices .........................................•..•.......... Description of stations................................................... 2 Definition of tenns........... • . 2 ILLUSTRATIONS Location of active gaging stations in Texas, October 1970 .•.•.•.••..•••••..•.. 1n pocket TABLES Table 1. Streamflow, quality, and reservoir-content stations •.•.•... ~........ 3 2. Low-fla.o~ partial-record stations.................................... 18 3. Crest-stage partial-record stations................................. 22 4. Miscellaneous sites................................................. 27 5. Tide-level stations........................ ........................ 28 ii INDEX OF SURFACE WATER STATIONS IN TEXAS OCTOBER 1970 The U.S. Geological Survey's investigations of the water resources of Texas are con ducted in cooperation with the Texas Water Development -

ECOLOGY of NORTH AMERICAN FRESHWATER FISHES

ECOLOGY of NORTH AMERICAN FRESHWATER FISHES Tables STEPHEN T. ROSS University of California Press Berkeley Los Angeles London © 2013 by The Regents of the University of California ISBN 978-0-520-24945-5 uucp-ross-book-color.indbcp-ross-book-color.indb 1 44/5/13/5/13 88:34:34 AAMM uucp-ross-book-color.indbcp-ross-book-color.indb 2 44/5/13/5/13 88:34:34 AAMM TABLE 1.1 Families Composing 95% of North American Freshwater Fish Species Ranked by the Number of Native Species Number Cumulative Family of species percent Cyprinidae 297 28 Percidae 186 45 Catostomidae 71 51 Poeciliidae 69 58 Ictaluridae 46 62 Goodeidae 45 66 Atherinopsidae 39 70 Salmonidae 38 74 Cyprinodontidae 35 77 Fundulidae 34 80 Centrarchidae 31 83 Cottidae 30 86 Petromyzontidae 21 88 Cichlidae 16 89 Clupeidae 10 90 Eleotridae 10 91 Acipenseridae 8 92 Osmeridae 6 92 Elassomatidae 6 93 Gobiidae 6 93 Amblyopsidae 6 94 Pimelodidae 6 94 Gasterosteidae 5 95 source: Compiled primarily from Mayden (1992), Nelson et al. (2004), and Miller and Norris (2005). uucp-ross-book-color.indbcp-ross-book-color.indb 3 44/5/13/5/13 88:34:34 AAMM TABLE 3.1 Biogeographic Relationships of Species from a Sample of Fishes from the Ouachita River, Arkansas, at the Confl uence with the Little Missouri River (Ross, pers. observ.) Origin/ Pre- Pleistocene Taxa distribution Source Highland Stoneroller, Campostoma spadiceum 2 Mayden 1987a; Blum et al. 2008; Cashner et al. 2010 Blacktail Shiner, Cyprinella venusta 3 Mayden 1987a Steelcolor Shiner, Cyprinella whipplei 1 Mayden 1987a Redfi n Shiner, Lythrurus umbratilis 4 Mayden 1987a Bigeye Shiner, Notropis boops 1 Wiley and Mayden 1985; Mayden 1987a Bullhead Minnow, Pimephales vigilax 4 Mayden 1987a Mountain Madtom, Noturus eleutherus 2a Mayden 1985, 1987a Creole Darter, Etheostoma collettei 2a Mayden 1985 Orangebelly Darter, Etheostoma radiosum 2a Page 1983; Mayden 1985, 1987a Speckled Darter, Etheostoma stigmaeum 3 Page 1983; Simon 1997 Redspot Darter, Etheostoma artesiae 3 Mayden 1985; Piller et al. -

Stormwater Management Program 2013-2018 Appendix A

Appendix A 2012 Texas Integrated Report - Texas 303(d) List (Category 5) 2012 Texas Integrated Report - Texas 303(d) List (Category 5) As required under Sections 303(d) and 304(a) of the federal Clean Water Act, this list identifies the water bodies in or bordering Texas for which effluent limitations are not stringent enough to implement water quality standards, and for which the associated pollutants are suitable for measurement by maximum daily load. In addition, the TCEQ also develops a schedule identifying Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs) that will be initiated in the next two years for priority impaired waters. Issuance of permits to discharge into 303(d)-listed water bodies is described in the TCEQ regulatory guidance document Procedures to Implement the Texas Surface Water Quality Standards (January 2003, RG-194). Impairments are limited to the geographic area described by the Assessment Unit and identified with a six or seven-digit AU_ID. A TMDL for each impaired parameter will be developed to allocate pollutant loads from contributing sources that affect the parameter of concern in each Assessment Unit. The TMDL will be identified and counted using a six or seven-digit AU_ID. Water Quality permits that are issued before a TMDL is approved will not increase pollutant loading that would contribute to the impairment identified for the Assessment Unit. Explanation of Column Headings SegID and Name: The unique identifier (SegID), segment name, and location of the water body. The SegID may be one of two types of numbers. The first type is a classified segment number (4 digits, e.g., 0218), as defined in Appendix A of the Texas Surface Water Quality Standards (TSWQS). -

Kansas Stream Fishes

A POCKET GUIDE TO Kansas Stream Fishes ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ ■ By Jessica Mounts Illustrations © Joseph Tomelleri Sponsored by Chickadee Checkoff, Westar Energy Green Team, Kansas Department of Wildlife, Parks and Tourism, Kansas Alliance for Wetlands & Streams, and Kansas Chapter of the American Fisheries Society Published by the Friends of the Great Plains Nature Center Table of Contents • Introduction • 2 • Fish Anatomy • 3 • Species Accounts: Sturgeons (Family Acipenseridae) • 4 ■ Shovelnose Sturgeon • 5 ■ Pallid Sturgeon • 6 Minnows (Family Cyprinidae) • 7 ■ Southern Redbelly Dace • 8 ■ Western Blacknose Dace • 9 ©Ryan Waters ■ Bluntface Shiner • 10 ■ Red Shiner • 10 ■ Spotfin Shiner • 11 ■ Central Stoneroller • 12 ■ Creek Chub • 12 ■ Peppered Chub / Shoal Chub • 13 Plains Minnow ■ Silver Chub • 14 ■ Hornyhead Chub / Redspot Chub • 15 ■ Gravel Chub • 16 ■ Brassy Minnow • 17 ■ Plains Minnow / Western Silvery Minnow • 18 ■ Cardinal Shiner • 19 ■ Common Shiner • 20 ■ Bigmouth Shiner • 21 ■ • 21 Redfin Shiner Cover Photo: Photo by Ryan ■ Carmine Shiner • 22 Waters. KDWPT Stream ■ Golden Shiner • 22 Survey and Assessment ■ Program collected these Topeka Shiner • 23 male Orangespotted Sunfish ■ Bluntnose Minnow • 24 from Buckner Creek in Hodgeman County, Kansas. ■ Bigeye Shiner • 25 The fish were catalogued ■ Emerald Shiner • 26 and returned to the stream ■ Sand Shiner • 26 after the photograph. ■ Bullhead Minnow • 27 ■ Fathead Minnow • 27 ■ Slim Minnow • 28 ■ Suckermouth Minnow • 28 Suckers (Family Catostomidae) • 29 ■ River Carpsucker • -

Index of Surface-Water Stations in Texas, January 1989

INDEX OF SURFACE-WATER STATIONS IN TEXAS, JANUARY 1989 Compiled by Jack Rawson, E.R. Carrillo, and H.D. Buckner U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Open-File Report 89-265 Austin, Texas 1989 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR DONALD PAUL MODEL, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Dallas L. Peck, Director For additional information Copies of this report can write to: be purchased from: District Chief U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Books and Open-File Reports 8011 Cameron Road Federal Center, Bldg. 810 Austin, Texas 78753 Box 25425 Denver, Colorado 80225 CONTENTS Page Introduction.......................................................... 1 Definition of terms................................................... 2 Availability of data .................................................. 3 ILLUSTRATIONS Plate 1. Map showing the locations of active surface-water stations in Texas, January 1989.................................... In pocket 2. Map showing the locations of active partia1-record surface- water stations in Texas, January 1989..................... In pocket TABLES Table 1. Streamflow, quality, reservoir-content, and partial-record stations maintained by the U.S. Geological Survey in cooperation with State and Federal agencies............... 5 111 INDEX OF SURFACE-WATER STATIONS IN TEXAS JANUARY 1989 Compi1ed by Jack Rawson, E.R. Carrillo, and H.D. Buckner INTRODUCTION The U.S. Geological Survey's investigations of the water resources of Texas are conducted in cooperation with the Texas Water Development Board, river authorities, cities, counties, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, Interna tional Boundary and Water Commission, and others. Investigations are under the general direction of C.W. Boning, District Chief, Texas District. The Texas District office is located at 8011A Cameron Road, Austin, Texas 78753. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Jenny Wrast Oakley 2700 Bay Area Blvd. | MC 540 | Houston, TX 77058 [email protected] | (281) 283-3947 www.eih.uhcl.edu EDUCATION Ph.D. Marine Biology Interdisciplinary Program, Texas A&M University, 2019 Dissertation: “Coastal Health Index for the Northern Gulf of Mexico: Moving towards Meaningful Ecosystem-Based Management.” M.S. Biology, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi, 2008 Thesis: “Spatial and Temporal Variability in Food Web Structure on Subtidal Oyster Reefs in Lavaca Bay, Texas.” B.S. Biology, Texas A&M University-Corpus Christi, 2006 Minor in Chemistry. PROFESSIONAL BACKGROUND Adjunct Faculty January 2021-Present College of Science and Engineering, University of Houston-Clear Lake, Houston TX -Instruct 1 section of Conservation Biology (BIOL 5534) Associate Director, Research Programs December 2020-Present Environmental Institute of Houston, University of Houston-Clear Lake, Houston TX -Manage EIH Environmental Research Department -Development and implementation of research budget -Responsible for research program policy, long-range forecasting, and strategic planning -Supervise research grants: scheduling, study design, data analysis, training and quality assurance Environmental Scientist September 2010-December 2020 Environmental Institute of Houston, University of Houston-Clear Lake, Houston TX -Supervise EIH Environmental Research Department -Grant and proposal writing -Data Analysis and final report writing Graduate Assistant Non-Teaching (GANT) January 2015-May 2015 Texas A&M University, College Station,