The Life and Times Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Galileo in Early Modern Denmark, 1600-1650

1 Galileo in early modern Denmark, 1600-1650 Helge Kragh Abstract: The scientific revolution in the first half of the seventeenth century, pioneered by figures such as Harvey, Galileo, Gassendi, Kepler and Descartes, was disseminated to the northernmost countries in Europe with considerable delay. In this essay I examine how and when Galileo’s new ideas in physics and astronomy became known in Denmark, and I compare the reception with the one in Sweden. It turns out that Galileo was almost exclusively known for his sensational use of the telescope to unravel the secrets of the heavens, meaning that he was predominantly seen as an astronomical innovator and advocate of the Copernican world system. Danish astronomy at the time was however based on Tycho Brahe’s view of the universe and therefore hostile to Copernican and, by implication, Galilean cosmology. Although Galileo’s telescope attracted much attention, it took about thirty years until a Danish astronomer actually used the instrument for observations. By the 1640s Galileo was generally admired for his astronomical discoveries, but no one in Denmark drew the consequence that the dogma of the central Earth, a fundamental feature of the Tychonian world picture, was therefore incorrect. 1. Introduction In the early 1940s the Swedish scholar Henrik Sandblad (1912-1992), later a professor of history of science and ideas at the University of Gothenburg, published a series of works in which he examined in detail the reception of Copernicanism in Sweden [Sandblad 1943; Sandblad 1944-1945]. Apart from a later summary account [Sandblad 1972], this investigation was published in Swedish and hence not accessible to most readers outside Scandinavia. -

On the Origins of the Gothic Novel: from Old Norse to Otranto

This extract is taken from the author's original manuscript and has not been edited. The definitive, published, version of record is available here: https:// www.palgrave.com/gb/book/9781137465030 and https://link.springer.com/book/10.1057/9781137465047. Please be aware that if third party material (e.g. extracts, figures, tables from other sources) forms part of the material you wish to archive you will need additional clearance from the appropriate rights holders. On the origins of the Gothic novel: From Old Norse to Otranto Martin Arnold A primary vehicle for the literary Gothic in the late eighteenth to early nineteen centuries was past superstition. The extent to which Old Norse tradition provided the basis for a subspecies of literary horror has been passed over in an expanding critical literature which has not otherwise missed out on cosmopolitan perspectives. This observation by Robert W. Rix (2011, 1) accurately assesses what may be considered a significant oversight in studies of the Gothic novel. Whilst it is well known that the ethnic meaning of ‘Gothic’ originally referred to invasive, eastern Germanic, pagan tribes of the third to the sixth centuries AD (see, for example, Sowerby 2000, 15-26), there remains a disconnect between Gothicism as the legacy of Old Norse literature and the use of the term ‘Gothic’ to mean a category of fantastical literature. This essay, then, seeks to complement Rix’s study by, in certain areas, adding more detail about the gradual emergence of Old Norse literature as a significant presence on the European literary scene. The initial focus will be on those formations (often malformations) and interpretations of Old Norse literature as it came gradually to light from the sixteenth century onwards, and how the Nordic Revival impacted on what is widely considered to be the first Gothic novel, The Castle of Otranto (1764) by Horace Walpole (1717-97). -

The Scientific Life of Thomas Bartholin1

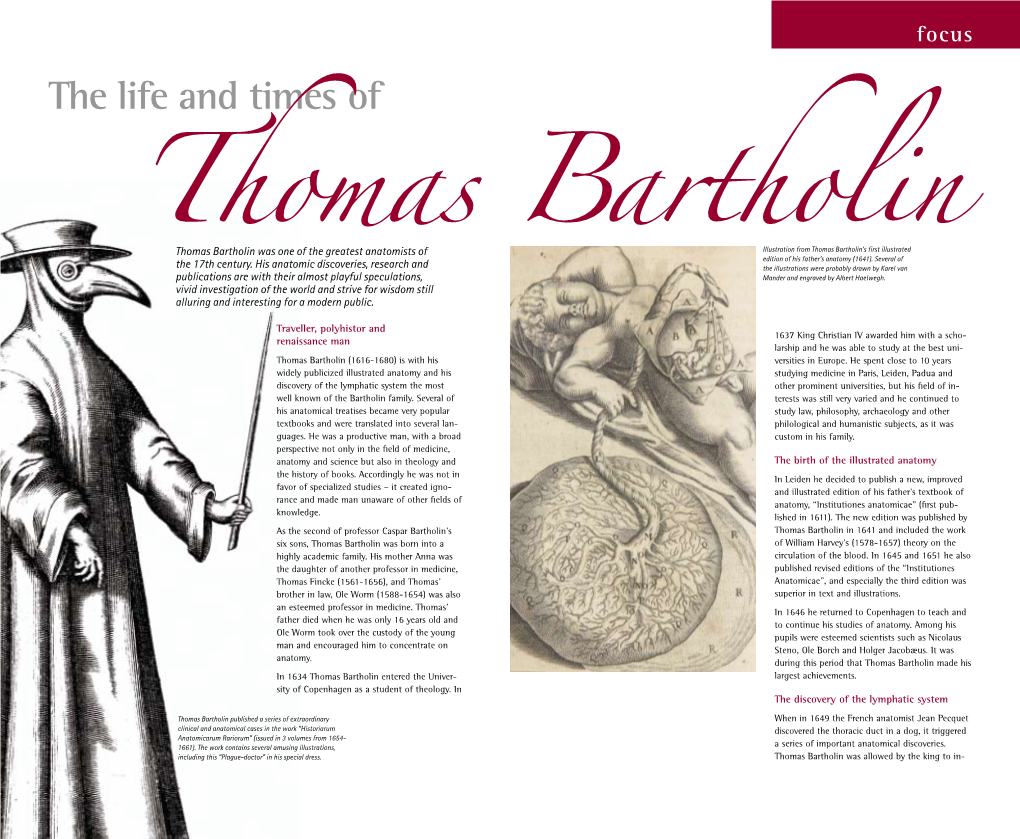

THE SCIENTIFIC LIFE OF THOMAS BARTHOLIN1 By JOHN H. SKAVLEM, M.D., CINCINNATI, OHIO HE name Bartholin was for a long life he was destined to lead. With the inten period of time so intimately asso tion of entering the ministry he first de ciated with the early development voted himself to the study of theology, but of scientific life in the University soon forsook this following and turned to of Copenhagen as to amply justify referencemedicine in which field the predestined Tto the institution of that period as the calling of anatomy soon prevailed upon school of the Bartholins. After the foster him. In 1636 he served as secretary to the ing of this scientific interest by Caspar first division of Worm’s medical institu Bartholin the culmination of this develop tion and shortly afterward went abroad, ment may be said to have been presented where his father’s reputation and Worm’s during the time when Thomas Bartholin, as recommendations gained for him warm anatomical professor, was the guiding power. receptions and advantageous distinction. Here he gathered about him a learned as He first went to Holland, which was at semblage of disciples both Danish and that time one of the scientific literary foreign. Because of the general use of Latin centers of the world, and studied at Leyden. in his scientific teachings he was able to deal While there he was urged by several book with students of all tongues and the result dealers to prepare a new illustrated edition was the establishment of a school of men of his father’s anatomy. -

Meaningful Memories Colloquium at Aarhus University Wednesday 15Th April 2020, 12.30 – 18.00 Place: 1483-312 IMC Meeting Room

Meaningful Memories Colloquium at Aarhus University Wednesday 15th April 2020, 12.30 – 18.00 Place: 1483-312 IMC Meeting Room Programme 12.30 Prof. Dr. Marianne Pade, School of Culture and Society, Classical Philology, Aarhus University Canons and archive in Early Modern Latin 13.00 Trine Arlund Hass, PhD, HM Queen Margrethe II’s Distinguished Postdoc, The Danish Academy in Rome & Aarhus University Remembering Caesar: Mnemonic Aspects of Intertextuality in Erasmus Lætus’ Romanorum Cæsares Italici (1574) 13.30 Anders Kirk Borggaard, PhD Fellow, Cultural Encounter, Aarhus University When Aneas picked up the Bible: Constructing a memory of King Christian III on a foundation of Virgil and Holy Scripture 14.00 Coffee 14.30 Lærke Maria Andersen Funder, PhD, Part-time lecturer, Centre for Museology, Aarhus University Re-membering the ideal museum; The reception of Museum Wormianum in early modern museography 15.00 Maren Rode Pihlkjær, Cand.mag. Changing cultural memory through translation: A new understanding of democracy 15.30 Dr. Johann Ramminger, Thesaurus Linguae Latinae-Institute at the Bavarian Academy of Sciences, Munich Annius of Viterbo’s Antiquitates: An alternative cultural memory 16.00 Coffee 16.15 Matthew Norris, PhD, Research fellow, Department of the History of Ideas and Science, Lund University. In Search of the Three Crowns: Conserving, Restoring, and Reproducing Cultural Memory in Early Modern Sweden 17.15 -18.00: Reception Book of abstracts Canons and archive in Early Modern Latin Prof. Dr. Marianne Pade, School of Culture and Society, Classical Philology, Aarhus University Early Modern Latin, the variety of Latin in use between c. 1350- 1700, holds a special place among the languages of the period: It had no native speakers, many of its users held up Ancient Latin as a standard to emulate, and it has therefore often been discarded as a mechanical copy of its model, a dead language. -

Stensen's Myology in Historical Perspective Author(S): Troels Kardel Source: Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, New Series, Vol

Stensen's Myology in Historical Perspective Author(s): Troels Kardel Source: Transactions of the American Philosophical Society, New Series, Vol. 84, No. 1, Steno on Muscles: Introduction, Texts, Translations, (1994), pp. 1-vi Published by: American Philosophical Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1006586 Accessed: 24/06/2008 03:15 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=amps. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org A&-&.4 Portrait of Niels Stensen as scientist to the Court of the Grand Duke of Tuscany. -

Ole Worm Christensen (WHO 1951-2004)

Ole Worm Christensen (WHO 1951-2004) Please tell us about your youth. I was born in Aarhus/Denmark in 1921 and grew up in a village in Seeland where my father was a medical practitioner. Please tell us about your education. Having completed my secondary school education, I entered the Medical Faculty of the University of Copenhagen in 1939 and obtained my medical degree in 1949. I further obtained a DPH at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in 1957. During my WHO career I attended several public health and management courses. Give us a brief history of your working experience – before WHO. Following hospital service to obtain my jus practicandi I joined the International UNICEF- Scandinavian Red Cross Tuberculosis Control (ITC) campaigns in Yugoslavia and Pakistan (1950/51). What were your reasons for joining WHO and when did you join? Although I was determined to return to Denmark to start a clinical career, I was tempted by and accepted in 1951 an offer, from the then only three year old World Health Organization, for an assignment in the field of tuberculosis control. My experience in Yugoslavia and Pakistan had convinced me of the potential and impact of public health operations. But the assignment was only to be for one year. Then it eventually ended up with more than fifty years of a - to me - most gratifying life with WHO. Please describe your career progression, responsibilities, services in countries, regions & HQs My initial assignment, from 1951 to 1953 , was that of medical officer/team leader responsible for TB surveys and BCG campaigns in Pakistan, Libya and Ethiopia *) starting at the level of medical specialist moving to P3 medical officer. -

Samuel Doody and His Books

Samuel Doody and his Books David Thorley Based on title page inscriptions, the online catalogue of Sloane Printed Books identifies forty- one volumes as having been owned by ‘J. Doody’ or ‘John Doody’.1 Typically, these inscriptions have been taken to indicate that the books were ex libris John Doody (1616-1680) of Stafford, the father of the botanist and apothecary Samuel Doody (1656-1706), but he may not (or at least may not always) be the John Doody to whom the inscriptions refer.2 While it is plausible that several of these books did belong to that John Doody, it is impossible that all of them were his: at least seven inscribed with the name were published after 1680, the year of his death. Only two books can certainly be said to have passed through his hands. First, a 1667 copy of Culpeper’s English translation of the Pharmacopœia Londinensis (shelfmark 777.b.3), bears several marks of ownership. On the reverse of the title page is inscribed in secretary characters ‘John Doodie his book’, while the phrase ‘John Doodie de Stafford’ appears on pp. 53 and 287, and the words ‘John Doodie de Stafford in Cometatu’ are written on to p. 305. A further inscription on the final page of Culpeper’s appendix giving ‘A Synopsis of the KEY ofGalen’s Method of Physick’ reads ‘John Doodie de Stafford ownth this booke and giue Joye theron to looke’. In two other places, longer inscriptions have been obliterated. Second, a 1581 edition of Dioscorides’s Alphabetum Empiricum (shelfmark 778.a.3) contains annotations in apparently the same hand that inscribed the 1667 Pharmacopœia. -

Download: Brill.Com/Brill-Typeface

The Body of Evidence Medieval and Early Modern Philosophy and Science Editors C.H. Lüthy (Radboud University) P.J.J.M. Bakker (Radboud University) Editorial Consultants Joel Biard (University of Tours) Simo Knuuttila (University of Helsinki) Jürgen Renn (Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science) Theo Verbeek (University of Utrecht) volume 30 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/memps The Body of Evidence Corpses and Proofs in Early Modern European Medicine Edited by Francesco Paolo de Ceglia LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Vesalius dissecting a body in secret. Wellcome Collection. CC BY 4.0. The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2019050958 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 2468-6808 ISBN 978-90-04-28481-4 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-28482-1 (e-book) Copyright 2020 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi, Brill Sense, Hotei Publishing, mentis Verlag, Verlag Ferdinand Schöningh and Wilhelm Fink Verlag. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

INVENTING the NORTH the Short History of a Direction

INVENTING THE NORTH The Short History of a Direction by Bernd Brunner Sample Translation by Dr. Lori Lantz Non-Fiction/Cultural History 240 pages Publication date: September 2019 World rights with Kiepenheuer & Witsch GmbH & Co. KG Iris Brandt ( [email protected] ) Aleksandra Erakovic ( [email protected] ) 1 The sailor cannot see the North, but knows the needle can. Emily Dickinson 2 3 THE UNICORN OF THE NORTH Let’s venture a look into the cabinet of curiosities in Copenhagen belonging to Ole Worm, the royal antiquary of the Dano-Norwegian Realm. Or, more accurately, the engraving of it that a certain G. Wingendorp prepared in 1655. This image forms the frontispiece of the book Museum Wormianum, in which Worm explains the origins of many objects in his fascinating collection. With a little imagination, the viewer can identify a bird at the right-hand edge of the picture as a giant auk. According to the account in the book, it was sent to Worm from the Faroe Islands and spent the rest of its life as the antiquary’s pet. The last of these now-extinct flightless seabirds were spotted on an island off the coast of Iceland in 1844. A miniaturized polar bear appears as well, hanging from the ceiling next to a kayak. On the left side, a pair of skis and an assortment of harpoons and arrows decorate the back wall. Closer to the front, an object pieced together of oddly formed parts stands at an angle below several sets of antlers. It’s a stool made of a whale’s vertebrae. -

Bulletin of the Geological Society of Denmark, Vol. 57, Pp. 1–24

On the origin of natural history: Steno’s modern, but forgotten philosophy of science JenS MOrten HanSen Hansen, J. M. 2009–11–01. On the origin of natural history: Steno’s modern, but forgotten philosophy of science © 2009 by Bulletin of the Geological Society of Denmark, Vol. 57, pp. 1–24. ISSn 0011– 6297. (www.2dgf.dk/publikationer/bulletin) https://doi.org/10.37570/bgsd-2009-57-01 nicolaus Steno (niels Stensen, 1638–86) is considered to be the founder of geology as a discipline of modern science, and is also considered to be founder of scientific conceptions of the human glands, muscles, heart and brain. With respect to his anatomical results the judgment of posterity has always considered Steno to be one of the founders of modern anatomy, whereas Steno’s paternity to the me thods known to day of all students of geology was almost forgotten during the 130 yr from 1700 to 1830. Besides geology and anatomy there are still important sides of Steno’s scientific contributions to be rediscovered. Steno’s general philosophy of science is one of the clearest formulated philosophies of modern science as it appeared during the 17th Century. It includes • separation of scientific methods from religious arguments, • a principle of how to seek “demonstrative certainty” by demanding considerations from both reductionist and holist perspectives, • a series of purely structural (semiotic) principles developing a stringent basis for the pragmatic, historic (diachronous) sciences as opposed to the categorical, timeless (achronous) sciences, • “Steno’s ladder of knowledge” by which he formulated the leading principle of modern science i.e., how true knowledge about deeper, hidden causes (“what we are ignorant about”) can be approached by combining analogue experiences with logic reasoning. -

L Anguages by G Erman , F Lemish and D Utch H Umanists (1555–1723)

T HE R EPRESENTATION OF THE S CANDINAVIAN L ANGUAGES BY G ERMAN, F LEMISH AND D UTCH H UMANISTS (1555–1723) By Luc de Grauwe European humanists took a great interest, not only in the origins of their own mother tongues, but also in the classification of cognate languages. Amongst other things, this led scholars from the Continental West Germanic area (i.e. the territory of present-day German and Dutch-Flemish) to study the place and characteristics of the Scandinavian languages within the Germanic language family. The present article presents and discusses the views of C. Gessner, J.G. Becanus, B. Vulcanius, J.J. Scaliger, F. Junius, J. Vlitius and L. ten Kate with regard to this topic. Covering the period from 1555 to 1723, their work displays a gradual improvement in scientific qual- ity and even prefigures many insights of modern linguistics. Not only did these scholars recognize the individuality of the different Scandinavian lan- guages (with the exception of Faroese), they also referred to them as sepa- rate linguae, thus reflecting, or at least foreshadowing, the Nordic varieties’ own ongoing development into distinct standard languages. In this contribution I would like to give an overview of the attention paid to the Nordic, or Scandinavian, languages and their classification by a series of renowned humanist scholars from the “Continental West Germanic” area, that is, the area where German and Dutch, including Flemish, are spoken nowadays. They are, in chronological order, Conrad Gessner (1555, 1561), Goropius Becanus (1569), Bonaventura Vulcanius (1597), Josephus Justus Scaliger (1599), Franciscus Junius (1655, 1665), Janus Vlitius (1664), and Lambert ten Kate (1723). -

THOMAS BARTHOLIN on the Burning of His Library on Medical

THOMAS BARTHOLIN On The Burning of His Library and On Medical Travel translated by Charles D. O'Malley * * * THE UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS LIBRARIES University of Kansas Publications Library Series UNIVERSITY OF KANSAS PUBLICATIONS Library Series Editor, ROBERT L. QUINSEY 1. University of Kansas: List of Publications Compiled by Mary Maud Smelser 1935 2. University of Kansas Graduate School Theses, 1888-1947 Compiled by Bessie E. Wilder 1949 Paper, $1.50 3. Two Augustan Booksellers: John Dunton and Edmund Curll by Peter Murray Hill 1958 Paper, $1.00 4. New Adventures Among Old Books: An Essay in Eighteenth Century Bibliography by William B. Todd 1958 Paper, $1.00 5. Catalogues of Rare Books: A Chapter in Bibliographical History by Archer Taylor 1958 Paper, $1.50 6. What Kind of a Business Is This? Reminiscences of the Book Trade and Book Collectors by Jacob Zeitlin 1959 Paper, 50c 7. The Bibliographical Way by Fredson Bowers 1959 Paper, 50c 8. A Bibliography of English Imprints of Denmark by P. M. Mitchell 1960 Paper, $2.00 9. On The Burning of His Library and On Medical Travel, by Thomas Bartholin, translated by Charles D. O'Malley 1960 Paper, $2.25 The Library Series and other University of Kansas Publications are offered to learned societies, colleges and universities and other institutions in exchange for similar publications. All communica• tions regarding exchange should be addressed to the Exchange Librarian, University of Kansas Libraries, Lawrence, Kansas. Communications regarding sales, reviews, and forthcoming pub• lications of the Library Series should be addressed to the Editor, Office of the Director of Libraries, The University of Kansas, Law• rence, Kansas.